The King of Fruits

The pineapple and the aristocrat

Fran Beauman

A Single Seed thrown into the hot Bed of Fashion will produce an immeasurable crop—All must have their Fooleries as well as their Pineries; and the only struggle seems to be, whose Fruit shall be the largest and most talk’d of.

—James Ralph (1758)[1]

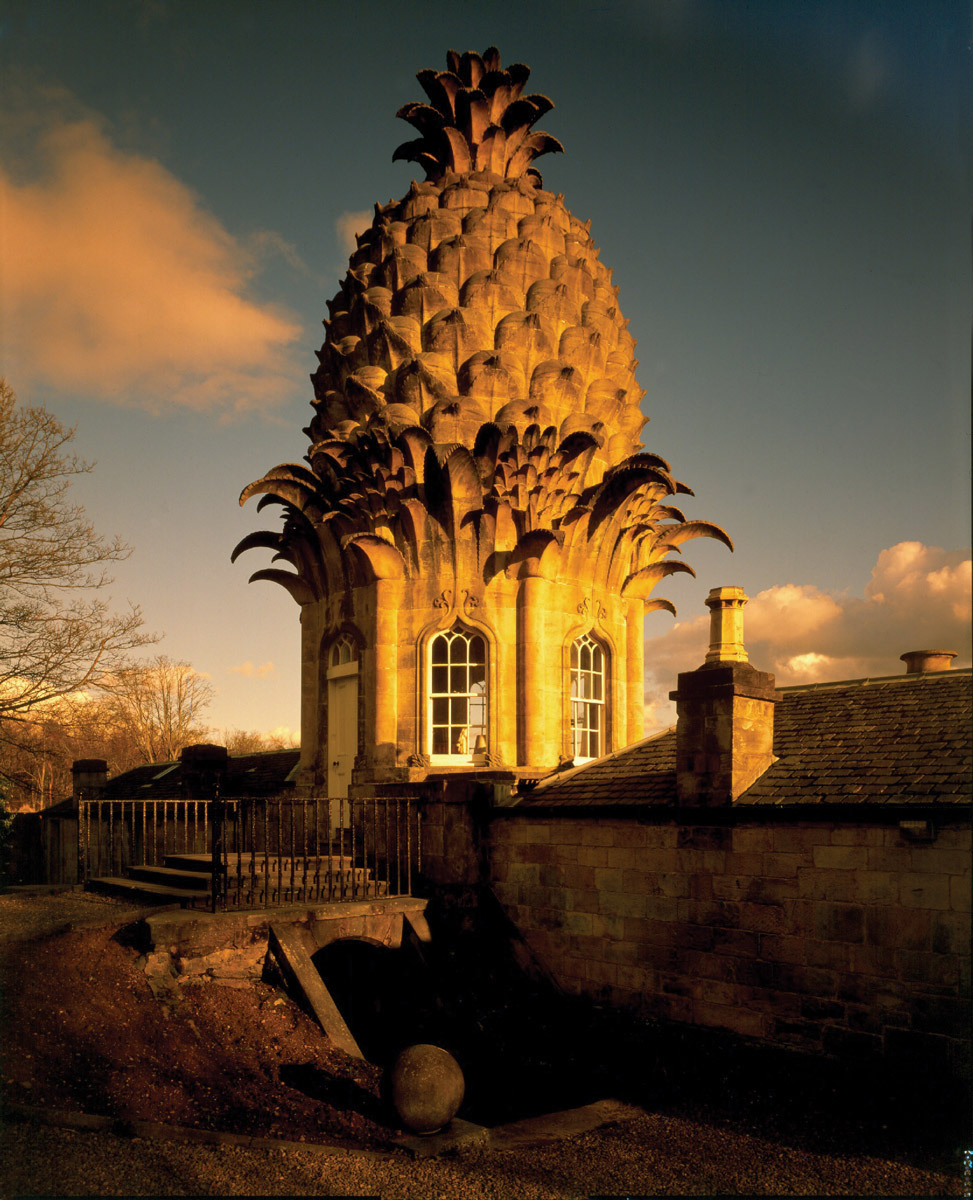

The Dunmore Pineapple is one of Britain’s most eccentric architectural splendors. It is also one of the few buildings in the world that is shaped like a fruit. Looming fifty-three feet high over the walled apple orchard of the Dunmore Park estate near Stirling, Scotland, the architect of this “garden folly” is not recorded in official records, although tradition ascribes it to Sir William Chambers. The elegant classical base dates from 1761, but the stone sculpture on top appears to have been a later addition commissioned by the fourth Lord Dunmore, John Murray.[2]

The fourth Lord Dunmore was the eldest son of William, the third Lord Dunmore, by his wife the Honorable Catherine Nairn. In 1770, at the age of thirty-eight, he was appointed governor of the colony of New York, and subsequently of Virginia as well. From the beginning of his tenure, he proved deeply unpopular. Hindered by his Scottish ancestry that made him appear boorish to the Virginian gentry, he won few friends with his impatient and abrupt manner. He was also rather cowardly: faced with the onset of the mass unrest that was to culminate in the War of Independence, his response was to retreat from the Governor’s Palace to the safety of a naval vessel moored offshore. Deemed even less forgivable at the time was the fact that he was the only British commander ever to free slaves. Having utterly failed to establish his dominance, he went on to suffer a series of humiliating losses in battle that culminated in defeat on Gwynn’s Island, Virginia, on 8 July 1776. It is likely that construction started on the Dunmore Pineapple on his return from the New World the same year.

To the contemporary onlooker, frittering away the equivalent of hundreds of thousands of dollars on a garden folly shaped like a pineapple might seem like a somewhat unusual decision. To begin with, it is a distinctly odd- looking fruit, with its royal crown, its armor-like rind, and its sword-like leaves. Why not build a folly in the shape of an apple, say, or a strawberry? Or, indeed, of something other than a fruit entirely? The answer lies in the complex cultural resonances that had accumulated like weeds around the pineapple in the years since Christopher Columbus first stumbled across it in Guadeloupe—in particular, in the fact that by the eighteenth century, it had emerged as one of the most potent status symbols of the age.

Dunmore Park was one of many great British country estates to possess its own productive pinery—that is, a hothouse designed solely for pineapples. In a country famed for its cold, wet weather, to attempt to propagate a tropical fruit like the pineapple, which needs an air and soil temperature of 60–70°F is clearly a preposterous project. And yet, for a few delicious moments in its history, this not only came to pass, but did so to a spectacular degree. By the 1770s, estates like Chatsworth, Sledmere, and Castle Howard cultivated their own specimens, sometimes hundreds at a time: “No garden is now thought to be complete,” wrote one contemporary botanist, “without a stove for raising of pine-apples.”[3]

The financial outlay required to grow pineapples outside of their natural habitat was astronomical. First, the pinery itself. It was estimated in 1764 that the construction costs alone of a pineapple stove 40 feet long and 12 feet wide were about £80. It would cost another £30 to stock it with pineapple plants, which in the early days had to be specially ordered and shipped from the Caribbean, while maintenance costs were also a consideration—about £21 a year. This was in addition to the extensive labor involved: the three to four years that each plant took to fruit were years of incredibly hard work for some unfortunate garden boy whose sole job it was to ensure that temperatures inside the pinery remained sufficiently high—stoking the stoves, raking the manure, even sleeping among the plants to ensure they did not burst into flames by mistake, as occasionally happened. With all this in mind, the average total cost of the cultivation of just one pineapple was about £80 (about $3000 in today’s money)—about the same as the cost of a new coach.[4]

Yet in the eighteenth century, the glory that ensured from offering one’s dinner guests this tiny taste of Paradise made it all seem worth it—for the master of the house, at least. “Look how rich I am,” it screeched in a decidedly undignified manner. The Prada handbag of its day, the pineapple essentially functioned as a response to a condition that today might be deemed “status anxiety”—the most impressive specimens made the rounds of urban dinner parties for weeks at a time, to be consumed only once they had begun to rot so much that they stank out the entire household.

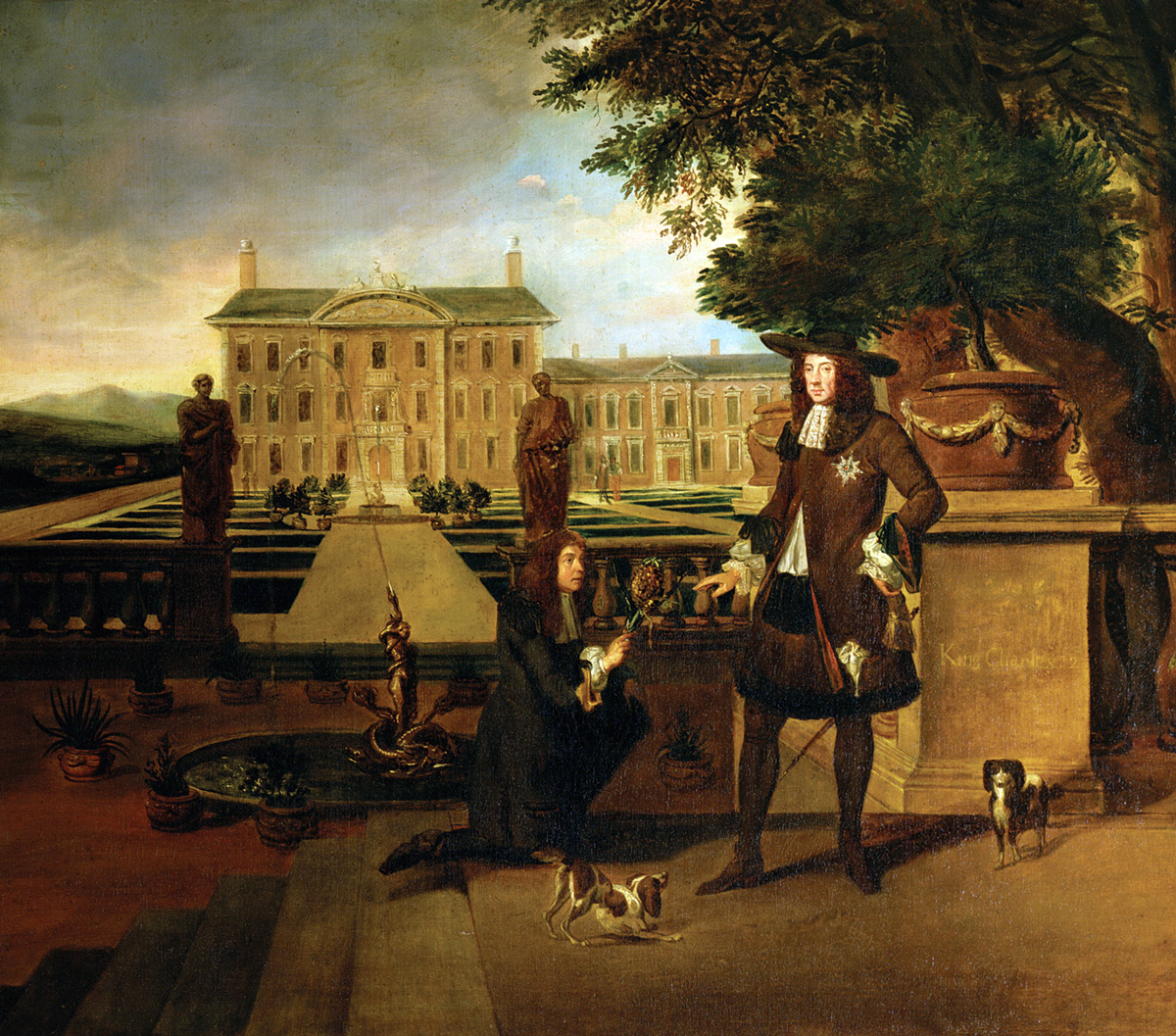

Ever since 1493, when the pineapple was first “discovered” by Columbus, it had been perceived in the West as the archetypically “exotic” fruit, inextricably intertwined with all that was wondrous about the New World; this explains the many rhapsodic accounts of the fruit written by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century explorers. The pineapple was a physical manifestation of Britain’s spectacularly successful appropriation of the New World as a whole. A 1766 poem by James Grainger describes how on the island of St Christopher’s, “the Sun’s child, the mail’d anana, yields / His regal apple to the ravish’d taste…”[5] It is a powerful metaphor for the way that the “mail’d” native Americans had been forced to “yield” themselves to those who “ravish’d,” that is the British. Thus every time a pineapple, which was so intimately associated with the New World, appeared at the dinner table, those present were reminded in an intensely visual way of the fruits of British victory overseas.

With consumerism becoming an increasingly central tenet of British society in this period, some of the cannier shopkeepers soon sought to market the pineapple to the upper classes in all shapes, forms, and materials. Here was a vessel through which the aristocracy was able to express a complicated but commonly understood cohort of contemporary values and mores within an arena that extended far beyond the garden or the dinner table. A pineapple in china or stone may not have been as impressive as the edible kind, but it did the job. The early 1760s saw the appearance of Josiah Wedgwood’s earliest pineapple designs, among them teapots, bowls, sauceboats, sugar dishes, and tea caddies. Also popular was a stone pineapple atop a gatepost. Situated in such a way that it served to mark out the limits of property, it was a way of very publicly differentiating between those who could afford the pineapple, whether in reality or in replica, and those who could not. Dunmore’s design for his garden folly may certainly be viewed in this light—there really was no danger that the neighbors would miss it.

Lord Dunmore arrived in New York to take up the post of Governor just as the British aristocracy’s mania for pineapples was being adopted with zest by Colonial American gentlemen anxious to copy fashions back home—despite the decidedly non-tropical climate which they too had to cope with. In October of that year, Mary Ambler was taken on a tour of Mount Clare, Charles Carroll’s Maryland estate. The sun was strangely hot for the time of year and her new shoes had pinched her the whole day through, but there was one sight that she did not fail to note in her diary: “There is a Green House with a good many Orange & Lemon Trees just ready to bear besides which he is now buildg a Pinery where the Gardr expects to raise about an 100 Pine Apples a Year. He expects to Ripen some next Summer.”[6] In Colonial America’s unpredictable environment, where finances were precarious, time and labor at a premium, and horticultural knowledge scarce, cultivating pineapples really was a bizarre hobby; yet Abraham Redwood in Rhode Island, Henry Laurens in South Carolina, and others all joined Carroll in taking to it enthusiastically.[7]

For those American gentlemen who chose not to nurture pineapples at home, there was another option: imports from the Caribbean, where they naturally grew in abundance. Some confectioners even hired pineapples out by the day; and no wonder, when a real-life pineapple had become the one essential guest to feature at all the society parties of the age. Hence in mansion houses up and down the country, men such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson would periodically display a pineapple at dinner as one way of asserting their place within this newly formed and deeply fragile social structure.[8] Washington in particular had a predilection for the fruit: “None pleases my taste as do’s the pine,” he confided in his diary during a trip to Barbados.[9]

Pineapples made of stone, silver, wood, or porcelain also found a role within American cultural life. Particularly popular was Staffordshire pineappleware, evidence of which has been recovered at Monticello and throughout Colonial America, while a rifle through the Pennsylvania Gazette during the 1760s throws up regular advertisements such as one placed by Joseph Stansbury in December 1769 announcing that he had a new range of pineapple teapots to offer his customers, should they care to call at his shop on Second Street near Arch Street in Philadelphia.[10] Stone pineapples, like those that still adorn the house built by William Byrd in Westover, Virginia, were common too.

The most often cited explanation for the pineapple’s ubiquity on America’s eastern seaboard is that the pineapple was a symbol of hospitality. When sea captains returned from trade missions with the West Indies, they were thought to have brought with them the native custom of placing a fresh pineapple at the entrance to their home to signify to the neighbors that visitors would be welcome. The theory is that colonial gentlemen then sought to echo this custom in a more permanent form. Contemporary sources, however, make no reference to this story. In fact, this more benign explanation only gained currency in the 1930s as historic house museums sought to recreate an idealized colonial past.

All the associations that surrounded an artistic representation of a pineapple in this period were, in fact, inherited wholesale from England, particularly status. On a gatepost, for example, it served to differentiate between the haves and the have-nots. In the frenzy to establish this kind of social differentiation that gripped Colonial America from around the 1730s, the pineapple—rare, strange, and expensive—proved a useful and distinctive marker. A less democratic response to the fruit than previously thought, it was nonetheless the one recognized at the time—not least by Lord Dunmore as he struggled to establish himself there during a time of frightening unrest.

The Dunmore Pineapple may also have been built for the associations it inspired in the viewer’s imagination: the fruit’s most immediate and appealing associations are the otherworldly antithesis of the dull grays and greens of rainy Britain. This is a manifestation of a yearning for the escapist “other” that was identified by James (now Jan) Morris as a kind of alter ego—“as though the British had another people inside themselves … who yearned to break out of their sad or prosaic realities, and live more brilliant lives in Xanadu.”[11] Perhaps for this reason, pineapples frequently featured in contemporary design manuals such as William Wrighte’s 1767 bestseller Grotesque Architecture.

In addition, the Dunmore Pineapple reflects a subversive streak in the British aristocracy, bursting out of the rigid repression of the classical form of the folly’s base, as extravagant in its way as Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill or William Beckford’s Fonthill. The triumph of the whim of the individual over the rule of authority was another trend typical of Enlightenment thinking, and the juxtaposition of European classicism in the form of the Dunmore Pineapple’s base and the New World influence in the form of the stone pineapple itself was relatively common in eighteenth- century architecture—though rarely in such an extreme form.

However, it is surely Dunmore’s experiences in the New World that hold the key to his garden folly. While there, he had been spectacularly unsuccessful in meeting his brief from the King of England to suppress the festering uprising in Virginia—he had proved incapable of asserting his authority over the foreign. While it may therefore seem odd that on his return he chose to erect such a potent reminder, perhaps—by representing the pineapple in classical, Western terms—he sought to translate a foreign, somewhat threatening entity into the familiar cultural setting of his apple orchard, a setting in which he felt able to control it, even dominate it, in a way he had so publicly failed to do in reality. In essence, the Pineapple at Dunmore Park is a spectacular attempt by the master of the house to contextualize the exotic on his own terms.

In 1787, Lord Dunmore was installed as the Governor of the Bahamas—not only had he apparently recovered from his traumatic experiences in Virginia, he also felt able to drag himself away from his beloved Pineapple for a few years. The recompense, perhaps, was that he was now surrounded by fields and fields of the real thing. While he stood up for the rights of Bahamian slaves (as he had in the American colonies), he again proved deeply unpopular, due to nepotism, crooked land speculation, and a strange obsession with building expensive new forts for no reason. Few were surprised when, in 1796, Dunmore was abruptly recalled by the British government. As a result, his most enduring legacy has in fact turned out to be the defiant architectural statement that is the Dunmore Pineapple. In the words of William Makepeace Thackeray in 1850: “And as the race of pine-apples, so is the race of Man.”[12]

- James Ralph, The Case of Authors by Profession or Trade Stated With Regard to Booksellers, the Stage, and the Public (London: Ralph Griffith, 1758), pp. 41–42.

- For more on the Pineapple, see the Landmark Trust documents at the building itself , as well as Glynn Headley and Wim Meulenkamp, Follies: A Guide to Rogue Architecture in England, Scotland and Wales (London: Jonathan Cape, 1990), p. 469; Stirlingshire: An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, 1963), p. 341; and George Mott and Sally Sample Aall, Follies and Pleasure Pavilions (London: Pavilion Books, 1989), p. 55.

- Richard Weston, Tracts on Practical Agriculture and Gardening (London: S. Hooper, 1769), p. 78.

- Museum Rusticum et Commerciale, vol. 1 (1764), p. 143.

- James Grainger, The Sugar-Cane: A Poem (Dublin: William Sleater, 1766), p. 30.

- Mary Ambler, “Diary of Mary Ambler,” Mrs. Gordon B. Ambler, ed., Virginia Magazine of History & Biography, no. 45 (1937), p. 166.

- For Abraham Redwood’s pineapples, see Alice G. B. Lockwood, ed., Gardens of Colony and State: Gardens and Gardeners of the American Colonies and of the Republic before 1840, vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1931), p. 217; for Henry Laurens’s pineapples, see Philip M. Hamer, ed., The Papers of Henry Laurens, vols. 5 and 7(Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1968) , p. 360 and p. 357, respectively.

- For George Washington’s pineapples, see George Washington to Lawrence Sanford (26 September 1769) and George Washington to Robert McMickan (10 May 1774) in Account Book 2 in The George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741–1799. For Thomas Jefferson’s pineapples, see James A. Bear, Jr., and Lucia C. Stanton, eds., Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany 1767–1826, vol. 1(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997) , p. 78.

- John Fitzpatrick, The Diaries of George Washington 1748–1799, vol. 1 (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1925), p. 27.

- The Pennsylvania Gazette, 28 December 1769.

- James Morris, Heaven’s Command (London: Faber, 1973), p. 6.

- William Makepeace Thackeray, The History of Pendennis, vol. 2, Peter L. Shillingsburg, ed. (London: Garland, 1991), p. 63.

Fran Beauman graduated with a degree in history from Cambridge University and now writes and hosts for television. Her first book, The Pineapple: King of Fruits, was published by Chatto & Windus in 2005. She divides her time between London and Los Angeles.