Colors / Red

Something dipped

Maggie Nelson

“Colors” is a column in which a writer responds to a specific color assigned by the editors of Cabinet.

I want to talk about something pushed all the way in then pulled all the way out, something dipped. As Lily Mazzarella says in a poem titled (appropriately) “Anger”:

Bleeding on wood seemed natural

I could dip fingers inside me and come out

with two red wands, true red.

The hands have become wands, alchemized by blood. They go in and come out, slick with evidence. Red is the evidence, the marker of what’s inside. It’s almost always a surprise, even when you expect it, even when it’s what you’re going for.

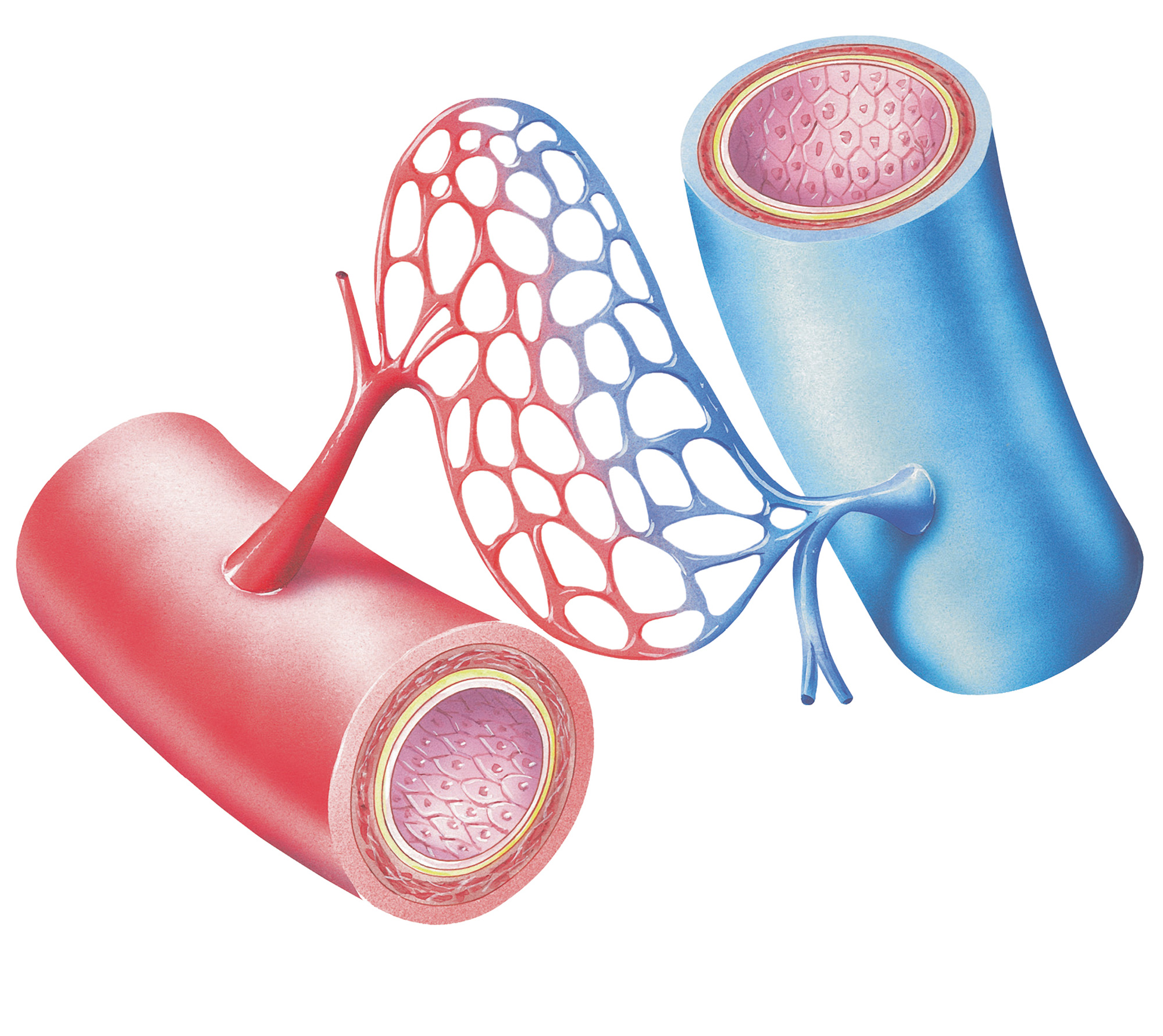

Blood is always red. I wasn’t entirely sure of this until today, so prevalent is the legend that blood is blue on its way back to the heart after having been depleted of its oxygen by organs hungry for it. Some say it’s children who erroneously hold this belief, due to all those anatomy charts in grade school that represent oxygenated blood as red, deoxygenated blood as blue. But by my count, just as many adults are under its sway. It is an alluring legend insofar as it asserts—not wrongly—that there are mysteries inside the body not available to our witness. It maintains that there is a “true” color of blood—blood in the wild—that any form of exposure (in this case, to oxygen, and human vision) would alter, or ruin. Like the giant squid (or at least the giant squid until 2004, when Japanese researchers finally managed to photograph an adult in its natural habitat), the legend of a wily, fugitive blue blood that transforms instantaneously upon being disturbed by outsiders is a happy superstition, the kind that can be inexplicably hard to give up. No one has seen the center of the earth, either. No one has seen a lot of things upon which our existence depends.

Some people say our blood appears blue from the outside because our veins are blue, but our veins aren’t really blue either. They only appear so due to a combination of factors, which include the overlying skin’s capacity to scatter and absorb different wavelengths of light, and the dark red color of the blood running through them. So what color are veins, really? Hard to say, as veins are vessels, whose form is generally determined by their content. A vein without blood is but a “hollow utensil”; think of the inert, gray tubing of a sausage.

Truth be told, there are no “true” colors—and perhaps that is the harder fact to swallow. As Wittgenstein advises, it is wrong to “just look at the colours in nature” in an attempt to understand them, for “looking does not teach us anything about the concepts of colour” (Remarks on Colour, §72). Elsewhere, however, he cajoles quite differently: “Don’t think, but look!” (Philosophical Investigations, §66). So what, or when, does looking teach us? What can we ask of things, except that they appear?