Artist Project / Reconciliation

Inside the confessional

S. Billie Mandle

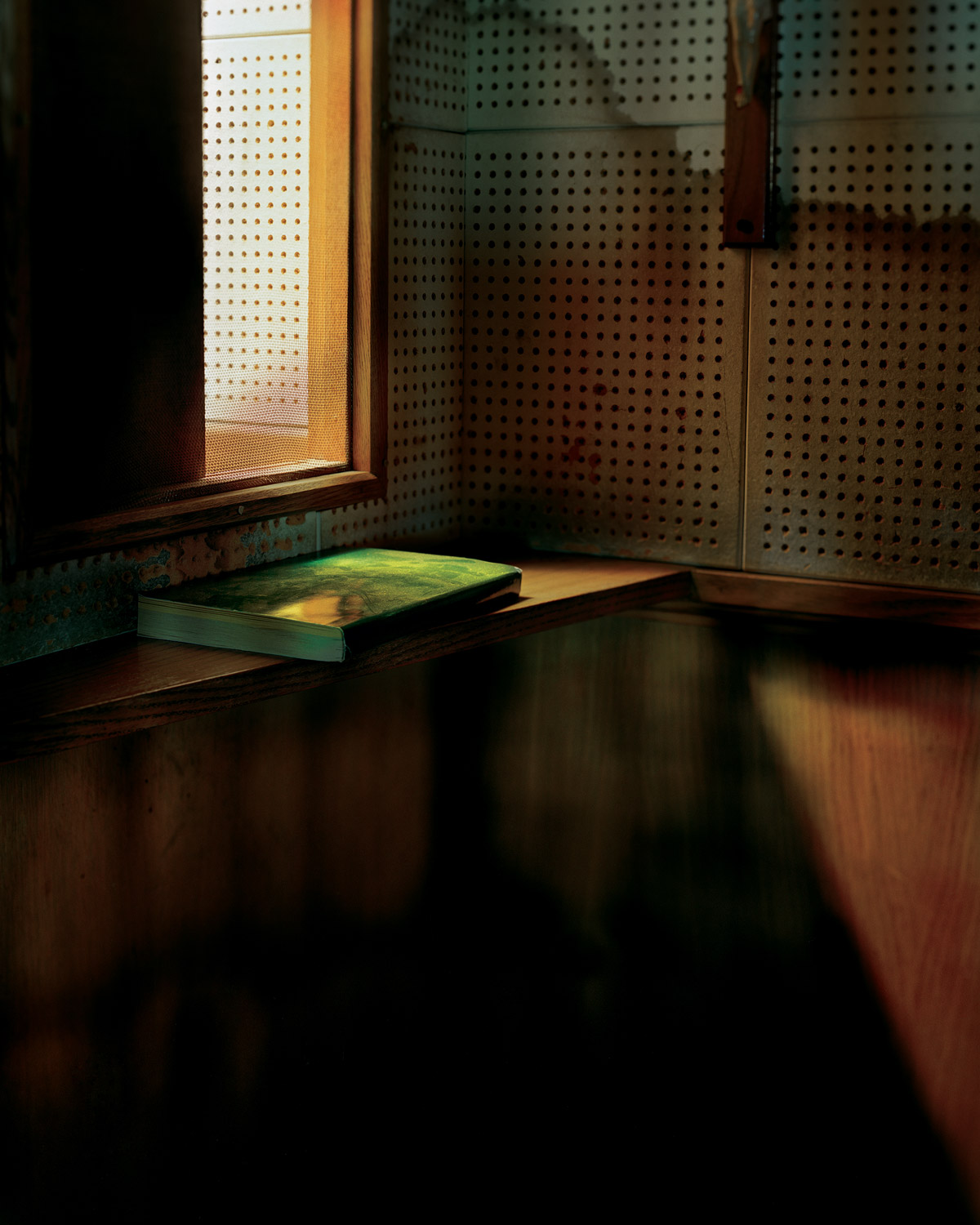

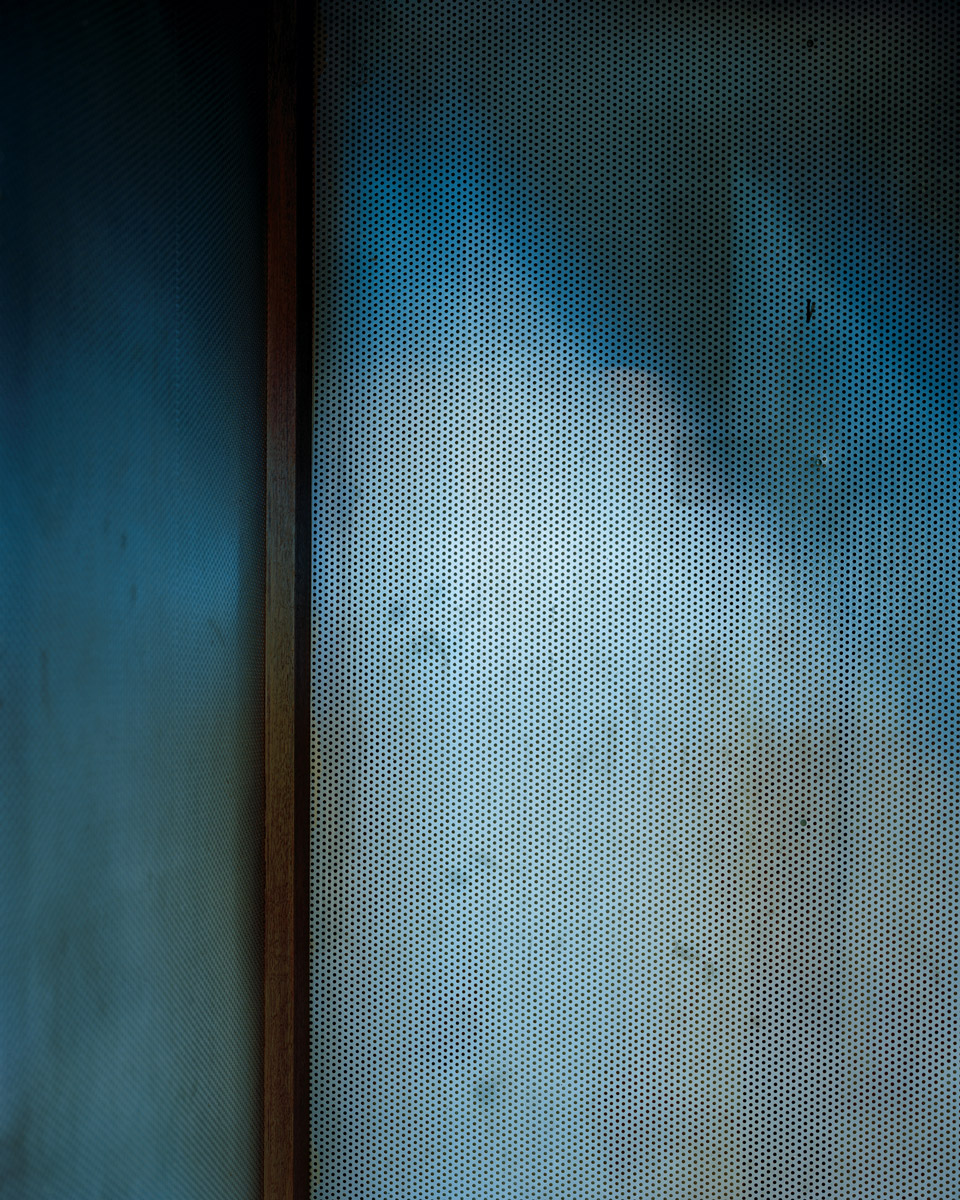

Saint Christopher, the enigmatic martyr and patron saint of travelers and children who bore the increasingly heavy Christ child across a deadly river before his own decapitation, bears brown water stains across his acoustical tiles. Light falls in displaced blades through his half-shut opening, across his little ledge, glaring the green cover of a volume lying there, angling down brown half-wall panels into the shadow realm. Saint Elizabeth—who vanishes from the Bible eight days after giving birth, when the men who are to circumcise her son arrive and try to name him Zechariah, whereupon she cries out, “No, he is to be called John!” for this is John the Baptist—is transformed, as in a Greek myth, into the black constellations of perforations in her soundproof paneling, then mantled with a jointed beam of light. And Saint Thomas More, intently principled, severe and merciless, who would not bow to kings, is a single, narrow ray plunging down a wooden wall, illuminating the grain in patterns reminiscent of a seizure patient’s EKG.

For seven years, S. Billie Mandle traveled across the United States, photographing church confessionals, searching, she has written, “for what might be left behind in these private rooms.” One recognition she came to—documented in her series Reconciliation, selections from which are presented here—is that the imprint of what these spaces not only witnessed but lived through was so palpably vivid that the rooms themselves assumed the character of the church’s heroic intercessors. These chambers carried scars suggesting martyrdom and sacrifice—as well as lyric plays of light and color, attesting to the possibility of grace. In both their luminous composure and rank degradation, we sense the extreme experiences that once quivered the air here, reflected by and absorbed into the well-worn surfaces. This may help explain why the pictures share a kind of harrowing “afterlife” quality with early Nan Goldin hotel rooms, when Goldin was helping to develop the language of “confessional art.”

Though the obligation and urge to confess may be among the primal religious responses to unsanctioned acts and wishes, it was at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 that the Roman Catholic Church first announced that church members must make at least one annual confession to avoid excommunication. This injunction was accompanied by the elimination of trial by ordeal, which some historians believe prompted legal courts to embrace confession, together with eyewitness testimony, as the core evidentiary props of secular law. The penitent, like the defendant, became “authenticated by the discourse of truth he was able or obliged to pronounce concerning himself,” writes the philosopher Chloë Taylor. Michel Foucault understood the new emphasis on the individual, embodied in the act of confession, as a critical stage in a greater process of “individualization.”[1]

It was at least 350 years after the council that private booths were introduced, with their visual cloaks and verbal apertures, consummating what’s been described as the church’s shift from “monstration to articulation.”[2] Among the earliest allusions to the contrivance of a box with a grille on one side through which the kneeling penitent could “pour the story of his sins into the ghostly father’s ears” occurs at Valencia in 1565.[3] A decade later, a reference to a rudimentary confessional in Milan crops up. Over the next ten years, boxes manifest in Aix and Toulouse. Throughout the seventeenth century, confessionals become increasingly ubiquitous.

Warnings about their susceptibility to abuse multiply in tandem with their spreading popularity, mostly as part of broader indictments of Popish doctrine and practices. As one early eighteenth-century Baptist sermon railed, the confessional presented “the utmost danger of violating all rules of modesty and decency, by putting questions, under pretence of searching sin to the bottom, which shall suggest wicked thoughts to the minds of young and inexperienced persons,” along with being calculated “to put the poor penitent wholly in the priest’s power with regard to estate, and reputation, and even life itself.”[4] This twofold indictment of these archaic containers remained the principal line of attack for generations. Yet on the question of power, Foucault, exploring how spatial relations evolved in tandem with the demands of new discursive practices, saw the rooms both enhancing opportunities for surveillance and facilitating the conferral of consolation. To Foucault, the confessional booth represented “the material crystallization of all the rules.”[5] Indeed, notwithstanding the perils of sequestered anonymity pertaining to these spaces, there were always those in and outside the church who saw therapeutic possibilities attached to their lack of transparency. Voltaire, among the church’s most vehement adversaries, characterized confession as an “excellent thing,” a “curb to the greater crimes,” and “the greatest curb on secret crimes.”[6]

Misgivings about the vulnerabilities of these booths to exploitative confessors, combined with diminished faith in the efficacy of forgiveness that could be dispensed from them, culminated in the 1970s with a precipitous drop-off in confessions. Numbers never really recovered. Recently, churches have been eliminating confessionals altogether and replacing them with “reconciliation” spaces that embrace face-to-face dialogues with priests. Conversations less concerned with judging and prescribing penitential measures than with cultivating frank exchanges modeled on talk therapy. Confession is now everywhere in our culture, but has blurred with self-expression—as such, it has become a right more than a responsibility, with authority invested in one’s own firsthand experience rather than any auditor, human or divine.

A twilit, elegiac atmosphere in many of Mandle’s images resonates with the confessional’s progressive disempowerment, and perhaps foreshadows their eventual total obsolescence. On balance, given their contributions to the bodily and spiritual afflictions of their occupants, this may be for the best. Yet, as Mandle’s photographs reveal, these rooms are also richly layered repositories of passions spent and forever pent inside. We may feel grateful that such an archive exists. The smooth glass cages of our devices will preserve no physical relics of our psychic suffering. In a poignant twist of faith, Mandle has created images that allow us to begin achieving reconciliation with the confessionals themselves.

—George Prochnik

- My overview of the history of the confessional is deeply indebted both to Chloë Taylor, The Culture of Confession from Augustine to Foucault (New York: Routledge, 2009) and to Alexander Freund, “‘Confessing Animals’: Toward a Longue Durée History of the Oral History Interview,” Oral History Review, vol. 41, no. 1 (Winter–Spring 2014).

- The genesis of this reading in relation to Foucault’s history of the confessional is traced in Brian T. Kaylor, Presidential Campaign Rhetoric in an Age of Confessional Politics (Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books, 2011); see in particular p. 194.

- Henry Charles Lea, A History of Auricular Confession and Indulgences in the Latin Church (Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co., 1896), pp. 394–396.

- Joseph Burroughs, The Popish Doctrine of Auricular Confession and Priestly Absolution Considered: A Sermon Preached at Salters-Hall, March 13, 1734 (London: Printed for J. Noon and J. Gray, 1735).

- Cited by Sara Mills in “Geography, Gender and Power,” in Space, Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography, ed. Jeremy W. Crampton and Stuart Elden (New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 50.

- Raphael Melia, A Treatise on Auricular Confession, Dogmatical, Historical, & Practical (Dublin and London: James Duffy, 1865), p. 94.

S. Billie Mandle is an artist living in western Massachusetts, where she is an assistant professor at Hampshire College.

George Prochnik is a Brooklyn-based author. His most recent book is Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem (Other Press, 2017). He has written for the New York Times, the New Yorker, Bookforum, and the Los Angeles Review of Books.