A Happy Madness

Images of drug use in the Casasola Archive

Jesse Lerner

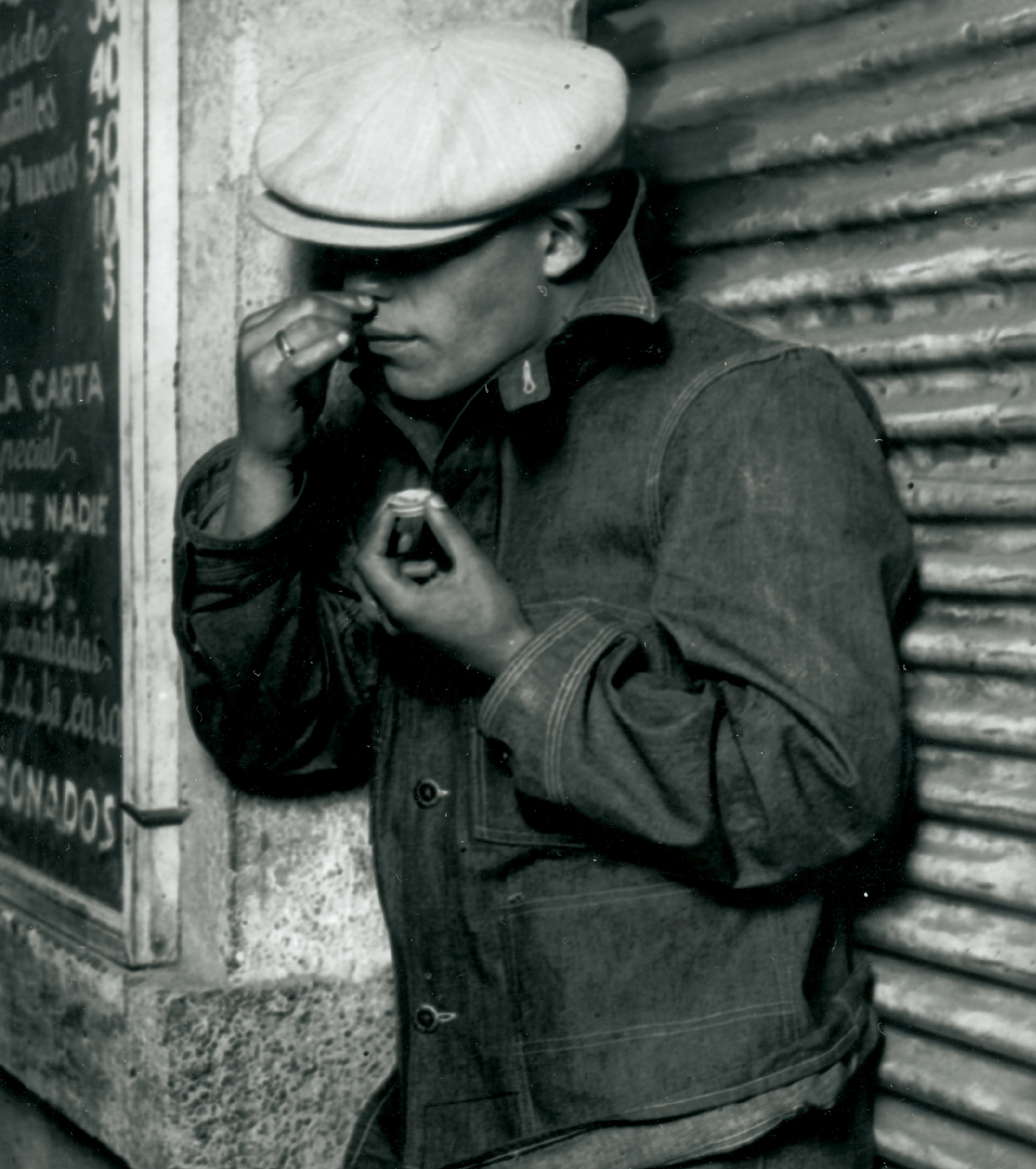

A floral curtain is pulled back to reveal a smartly dressed brunette from the 1930s reclining on a well-appointed bed. She stares mesmerized into space, seemingly transfixed by a point in space somewhere below and to the left of the camera’s lens. In her hands is an opium pipe, held at an angle above an extinguished burner, on which the camera, but not the subject’s gaze, is focused. Is this a cautionary image of moral decay, a celebration of the libertine and liberated pursuit of pleasure, or frank, non-judgmental reportage documenting urban vices? The absence of any clear editorial voice, and the matter-of-factness with which this and other illicit and typically invisible acts are presented for the camera, allow for a wide range of interpretations of these striking photographs of drug use in Mexico City in the 1920s and 1930s.

This and many other arresting pictures of high living in Tenochtitlan between the world wars are images from the Casasola Photo Agency, perhaps the most important photojournalistic outfit in early 20th-century Mexico. Agustín Victor Casasola and his younger brother Miguel began their careers as press photographers around 1900 working for the newspaper El Imparcial, for which they documented presidential travels and state ceremonies. The narrow limits on the freedom of the press made them, in effect, the dictator Porfirio Díaz’s propagandists during the final years of his rule, although they also produced photographs of the dictatorship’s darker side—photo-essays that could be interpreted as anti-government—of the poverty that was normally hidden from the camera behind the positivists’ façade of rational order, marble monuments, and scientific progress. They supplemented their work as journalists photographing weddings, first communions, public works projects, and the like. When Díaz left for exile in Europe, the Casasolas covered the story.

The revolution that followed changed photojournalism in Mexico definitively. When foreign journalists began flooding the country to report on the civil conflict that erupted in 1911, the brothers formed an agency with several colleagues to better contend with this new, more competitive environment. The Agencia Fotográfica Nacional, founded in 1912, grew into a wide-ranging archive of over half a million negatives, as the brothers began to acquire existing collections, beginning with the photo archives of their former employer, El Imparcial. The Casasola collection thus includes not only photographs taken by the two brothers, their children Agustín Jr. and Gustavo, and other family members, but also the work of over 400 other photographers.[1] Soon Miguel abandoned photography, at least temporarily, for a more active role as a combatant in the army of Alvaro Obregón.[2] Agustín Victor didn’t often leave the capital in pursuit of pictures, but in 1913, the conflict came to the city streets. While the Casasolas continued to photograph after the Revolution, producing images like those of the drug users for newspapers including El Universal, Excelsior, and El Demócrata, their business increasingly involved the marketing of their archive and the publication of visual histories that drew on their extensive holdings.[3]

Collectively, the Casasola images, now housed in the Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia’s Fototeca in Pachuca, Hidalgo, offer a cross section of (for the most part urban) society over the course of the first half of the 20th century. The archive is still almost synonymous with its powerful images of the revolution, any number of which have gained iconic status: the “Adelita” leaning out of the train car; Pancho Villa looking quite comfortable in the presidential chair, with a more ambivalent Zapata at his side. These are photographs that, after having been reproduced countless times, are ingrained in the imagination as the defining visual record of the first social revolution of the past century.[4] But given that the photographers whose work comprises the archive were active both before and after the armed conflict of the revolution, and given the sheer size of the collection, it should not be surprising that the Casasola archive involves much more than these well-known images of civil war. What is startling is that a segment of the archive contains an extensive record of drug use and abuse in the 1920s and 1930s. Some of the images seem clearly legible: policemen posing with quantities of confiscated contraband, the detailed record of the means and subterfuge involved in transporting drugs, and so on. But others present such a non-judgmental look at a topic that is typically absent from the photographic memory that one cannot but wonder: for whom were these images produced?

The images capture a moment in which drug use in Mexico was undergoing dramatic and rapid change. Two broad patterns defined drug use in the period prior to this era. One of these was centuries-old and employed herbs, cacti, and mushrooms as a means to access the supernatural. In pre-Columbian society, these were regulated and largely dominated by professional holy men, part of a variety of mechanisms that maintained the social order though controlling contact with the divine. Needless to say, with the Conquest, the Church did what it could to eliminate these practices, but to a great extent failed to do so. Instead, what frequently emerged after the arrival of the Spanish were syncretic practices that mixed and matched Catholic saints and iconography with the indigenous traditions of ritual hallucinogen usage. This is the yerbería mexicana that brought Artaud to the Sierra Tarahumara and the hippies to Huautla de Jiménez. The conflation of the Eucharist with pre-Cortesian peyote rites brought the Saints, the Virgin, and Christ to life for believers under the influence.[5]

Though we know the sacred use of drugs was commonplace in 19th- and early 20th-century Mexico, where the professed allegiance to Catholicism masked a vast diversity of religious practices, there is scant photographic documentation of this sort of use. The exception is the work of Karl Lumholtz, the Norwegian zoologist, ethnographer, photographer, and botanist, images created over extensive periods of travel and fieldwork. In 1890, after securing support of the American Museum of Natural History, Lumholtz traveled to the cliff dwellings of Arizona, and then to Sonora and Chihuahua. He returned to Mexico in 1892 to study and photograph the Tarahumaras. After exhibiting his photographs at the Chicago Columbian Exposition, he undertook his longest expedition. Between 1894 and 1897, Lumholtz spent extended periods living with the Coras and Huicholes. In 1898, he traveled to the northwest region of Mexico with the anthropologist Ales Hrdlicka to live with the Huicholes and the Tarahumaras, and he returned again in 1905 and 1909. In his photographic archive there are glimpses of the peyote rites that brought visions of the divine to the faithful.[6]

The other broad category of drug use during the Díaz dictatorship was a more recent phenomenon, and one less uniquely Mexican. As in many other parts of the world, middle-class citizens in the late 19th century indulged in a range of over-the-counter “energizing” pills and powders, typically cocaine or morphine derivatives. According to the memoirs of Francisco Rivera Avila, entitled When the Coca had no Cola, the marketing of these drugs through pharmacies continued well into the 1920s, despite the revolutionary-era legislation’s aims at eliminating the trade.[7] Though evidence is scarce, there is every reason to believe this market was prospering at the turn of the century. For the pre-revolutionary society of the Porfiriato, the stance taken regarding drug use was defined by social class, both that of the user and that of the individual passing judgment. One newspaper made this distinction clear: “Only in the spectacle of the drunk of the streets, half-naked, does alcohol terrify. The discreet drunk, well-dressed, passing in a car, is something else, respectable and decent.”[8] Marijuana was prevalent in Pre-revolutionary society, but it was a proletarian vice associated with prisons, the lumpen’s vasilada [meaning “to enjoy, especially when stoned”], and off-duty hours of enlisted men, and thus largely the purview of the guardians of public morality. References to the popular appreciation of pot are found in song and in slang expressions.

The drug use portrayed in the Casasola archives is different from the other cases; it is neither the mushroom trip into an ecstatic religious haze as practiced by the indigenous shaman, nor the polite Porfirian señoras popping the cocaine-laced “Dr. Ross’s Pills of Life” or some other ersatz medication. The Casasola archive seems to focus instead on the pastime of a new, cosmopolitan subject, testing the limits of freedom. It is again not in photography, but in popular songs, films, newspaper reports, poetry, and literature that we find the context that allows us to understand the world in which these photographs were created. There is much evidence of popular attitudes and manners to lead us to believe that recreational drug use was a part of an urban, bohemian underworld, an emergent, modern public space of altered sensation, accelerated rhythms, and exaggerated emotions. Here playboys, poets, movie starlets, artists, and flappers loitered in smart cafés and said to themselves, in the words of an anonymous writer in Revista de revistas, “From today on, when I am bored, very bored, very bored, so bored that neither Greig nor Chopin nor Beethoven nor Debussy can get me high enough, I take ether or ‘coco.’”[9] Germán List Arzubide, in his chronicle of the Estridentista movement, the vanguardist bad boys of Mexican arts and letters of the 1920s, reports on one wild party where “hygienic tobacco” was used, and a misogynistic new verse was first read:

That night, beyond all the almanacs, the squeaking doors of metropolitan horror opened. A Woman Chopped in Pieces surprised the sonnet writers that could not triangulate and did not want to know about women, and the shout of the academic parrots added enough green so that the reporters stayed up until dawn on the rooftops of the new horizon. The general staff of Estridentismo, with Maples Arce, pointed their loudspeaker to the road and Huitzilopoxtli, waking up from centuries of Manuel Horta and Panchito Monterde, gave time a hand by looping the loop.[10]A fiction film from Orizaba, Veracruz, from the same time as the Casasola images and the Estridentista text, also provides a context for understanding the photographs. Gabriel García Moreno’s feature-length film drama El puño de hierro [The Fist of Iron, 1927], the story of a young man’s experiment with heroin, avoids both List Arzurbide’s euphoric rhetoric and the moralizing hysteria of contemporary journalistic accounts (or a later film like Marijuana: el monstro verde [Marijuana, the Green Monster, 1936]). Here we see the casual experimentation with needles and opiates in the backrooms of cafés, a provincial version of the bohemian atmosphere that pervades the Casasola images. While the main narrative line of El puño de hierro seems to fulfill prohibitionist expectations, the film undercuts its own message of temperance with a coda that suggests all is well. The protagonist, coming to, and finding his friends frolicking at the beach and not mired in addiction and violence as he had dreamt, swears off further experiments with heroin. In dismissing the misadventures and tragedies depicted earlier in the film as nothing more than a bad dream induced by drugs, García Moreno seems to suggest that junk is little more than the harmless, youthful folly of the overly curious.[11]

This permissive attitude taken toward recreational drugs gave way to greater and greater efforts to prohibit and restrict. It has been argued that a gradual shrinking of spaces of tolerance in Mexico over the first part of the 20th century was one which, in the end, responded more to external interests, especially those of the North American agents of “moral hygiene,” than to national ones.[12] While changing international attitudes did in fact stir the state and its police into a repressive mode, arguments for and against specific drugs responded to internal political dynamics as well. The xenophobic violence targeting the Chinese immigrant community, a demagogic scapegoating cynically utilized as a political tool, found an ideal pretext for racial intolerance in opium.[13] The Casasola images coincide with a watershed in international efforts to control the global flow of opium and its derivatives, in which the Mexicans participated, beginning with the national ban imposed by Venustiano Carranza at the end of 1915.[14]

The present-day mores of narco-traffickers, with their powerful weapons and ostentatious lifestyles (the latter spawning what one architectural critic, Lawrence Herzog, calls “narchitecture,” those palatial monuments to poor taste), and “wars” for and on drugs are distant from what is visible in the Casasola images. Instead, we see a world where current prohibitions were barely in the process of being articulated, in which retailers were able to openly market the certain chemicals and organic products with characterizations such as “energizing,” “medicinal,” or “hygienic.” During that time, when experiments with opium or heroin were as likely to be understood recognized as a badge of sophistication than a symptom of a disease or a criminal behavior, Casasola’s photographers were able to create these arresting images of intoxication.

- This calculation was made by Ignacio Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba, who was charged with cataloguing the Casasola collection for the Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia’s Fototeca, in “A Fresh Look at the Casasola Archive,” History of Photography, vol. 20, no. 3 (Autumn 1996), p. 191.

- Gustavo Casasola’s role as a combatant in the Revolution is described in an interview with Gustavo and Mario Casasola by Adriana Malvido, La Jornada, 21 November 1991.

- The Casasola family published several multi-volume sets of images from their archive, most notably Álbum Histórico Gráfico (1921), Historia gráfica de la Revolución Mexicana (1942), and Seis Siglos de Historia Gráfica de México (1978).

- Images of the Mexican Revolution from the Casasola archive are reproduced in Jefes, heroes, y caudillos (Mexico City: Rio de la Luz, 1986); Gustavo Casasola, Historia gráfica de la Revolución Mexicana (México, Ed. Gustavo Casasola, 1942); and David Elliott, ed., Tierra y Libertad!: Photographs of Mexico 1900–1935 from the Casasola Archive (Oxford: St Martin’s Press, 1986). A broader selection of photographs from the archive appears in Agustín V. Casasola (Paris: Photo Poche, 1992), The World of Agustín Víctor Casasola (Washington, D.C.: Fondo del Sol Visual Arts and Media Center, 1984), and David Maawad et. al., Los inicios del México contemporáneo (Mexico City: FONCA/CONACULTA/Casa de las Imagenes/INAH, 1997). A selection of images of drug use and abuse from the archive appears in Ricardo Pérez Monfort, Yerba, goma, y polvo (Mexico City: Ediciones Era/Instituto Nacional de Antrologogía e Historia, 1999).

- Serge Gruzinski, Images at War: Mexico from Columbus to Blade Runner, 1492–2019, trans. Heather MacLean (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2001), pp. 170-172, and The Conquest of Mexico: The Incorporation of Indian Societies into the Western World, 16th–18th Centuries, trans. Eileen Corrigan (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993), pp. 220-221. See also Peter T. Furst, Alucinógenos y cultura (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1980).

- See Lumholtz’s books, which include reproductions of these images. Unknown Mexico (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1902); New Trails in Mexico (New York: Scribner, 1912); Symbolism of the Huichol Indians (New York: Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, 1900); and Decorative Art of the Huichol Indians (New York: Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, 1904).

- An untranslatable pun: cola in Spanish means tail. In Estampillas Jarochas (Veracruz: Instituto Veracruzano de Cultura, 1988). My translation.

- Diario Ilustrado, 2 November 1908, quoted in Ricardo Pérez Monfort, “Fragmentos de historia de las ‘drogas’ en México, 1870–1920,” in Hábitos, normas y escándalo: Prensa, criminalidad y drogas durante el porfiriato tardío (Mexico City: Plaza y Valdés, 1997), p. 168.

- Revista de revistas, 7 June 1925.

- Germán List Arzubide, El movimiento estridentista (Jalapa, Veracruz: Ediciones de Horizonte, 1927), p. 74.

- The Filmoteca of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México recently completed a restoration of this film that involved a re-editing of the existing materials. To what extent the re-edited version has altered the moral message of the film remains open for further study. For more on this film and García Moreno, see Dante Octavio Hernández Guzmán, Imágenes en movimiento en Orizaba (Orizaba, Veracruz: Comunidad Morelos, 2001), pp. 30-34, and Gabriel Ramírez, Crónica del cine mudo mexicano (Mexico City: Cineteca Nacional, 1989), pp. 234-235.

- Ricardo Pérez Montfort, “De vicios populares, corruptelas y toxicomanías,” in Juntos y medios revueltos: La ciudad de México durante el sexenio del General Cárdenas y otros ensayos (Mexico City: Ediciones Uníos, 2000), pp. 111-134.

- Juan Puig, Entre el río perla y el Nazas: La China decimonónica y sus braceros emigrantes, la colonia china de Torreón y la matanza de 1911 (Mexico City: CONACULTA, 1992), pp. 173 ff.; Jorge Gómez Izquierdo, El movimiento antichino en México, 1870-1934: Problemas del racismo y nacionalismo durante la Revolución Mexicana (Mexico City: Institúto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1991).

- David F. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotics Control (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973).

Jesse Lerner is a documentary filmmaker and editor-at-large of Cabinet.