Remedial Art History for the German Far Right

The new orientalism

Lily Scherlis

Billboards are a cornerstone of German election campaigns. The government provides each political party with a few minutes of televised ad time, preventing the costs of airtime from pricing underfunded candidates out of public view. Because there are strict limits on the frequency and length of TV and radio advertisements, campaigns traditionally compete for visibility outdoors and on paper. Though parties have recently taken to social media, pouring money into Silicon Valley, printed matter remains a force to reckon with. This past April, in advance of elections for the EU Parliament, an 1866 French Orientalist painting appeared around Berlin. The painting, The Slave Market by Jean-Léon Gérôme, depicts a naked, enslaved woman having her teeth examined by a prospective buyer. The woman has light skin and the three men surrounding her, peering evaluatively at her figure, have darker skin and are wearing outfits meant to evoke nineteenth-century Egypt. The painting was used to publicize the anti-immigration agenda of the far-right AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) party.

Since its establishment in 2013, the AfD has transformed from a small party of Euroskeptic elites into a populist anti-immigration (and often white nationalist) epidemic.[1] Founded by economics professor Bernd Lucke, it initially gained traction with well-educated Germans frustrated about bailing out southern European countries. The party polled 4.7 percent in the 2013 national parliamentary elections and received no seats in the Bundestag. Amid the influx of migrants in 2015, the AfD fractured, and a majority faction rallied around a new leader, vocal Islamophobe Frauke Petry, later regarded as a moderate voice within the party. After adopting fierce anti-immigration rhetoric, the party’s popularity snowballed alongside other far-right movements: in state elections this September, the AfD received 27.5 percent of the vote in Saxony and 23.5 percent in Brandenburg. In the May European Parliament elections, the AfD won eleven out of ninety-six German seats.

The Gérôme poster, a high-profile part of that election’s campaign, deploys the typical far-right tactic of racist and xenophobic paranoia mongering. At the top of the Gérôme poster, big white sans-serif lettering proclaims: “So that Europe doesn’t become Eurabia!”[2] “Eurabia” is a term associated with an Islamaphobic conspiracy theory that describes a hypothetical future version of Europe, one culturally and politically subservient to “Islamic powers.” Those who believe in Eurabia argue that Europe’s subordination is discreetly underway or already complete, helped along by profiting European politicians and powerful governmental lobbies.

The party was predictably derided for the poster’s ferocious racism. The thirty copies placed around Berlin were so frequently defaced or removed that the party had campaign workers running around replacing them almost daily.[3] The Clark Art Institute in Massachusetts, which owns the painting, strongly condemned the AfD’s usage. Though the image is in the public domain, the US museum wrote to the AfD urging them to cease and desist. Ronald Gläser, a party spokesperson, described this as “a futile attempt to gag the AfD,” asserting that the “public has the right to find out the truth about the possible consequences of illegal mass immigration.”[4]

• • •

The Eurabia theory was popularized by Gisèle Littman (writing under the pseudonym Bat Ye’or) in 2005.[5] Littman dated the birth of the conspiracy to the oil crisis of 1973, when the Arab League and the European Economic Community (later subsumed into the EU) established a short-lived conference system that aimed to stabilize economic and political relations between the two entities.[6] The term “Eurabia” is usually attributed to Littman, but before it was a conspiracy theory, it was a small French journal published by the European Coordinating Committee of Friendship Societies with the Arab World, which was founded in 1972.[7] A quarterly providing updates on developments in Euro-Arab cooperation, Eurabia published at least three issues beginning in 1975. Unlike Eurabia, Littman believes that the dialogue turned Europe into “an instrument of Arab policy,” citing instances of European condemnation of Israeli military behavior and increased anti-Americanism as symptoms of Arab political control.[8] Europe will become “a political satellite of the Arab and Muslim world” and fall under Islamic rule, causing the repression of white European culture. She goes on to claim that Jews and Christians have historically been required to “accept the restrictive and humiliating subordination to an ascendant Islamic power to avoid enslavement or death,” and that this repression is now an imminent threat across all of Europe due to the “active collusion” of pro-immigration European politicians. (Littman’s attitudes are perhaps marked by her biography: she was born Jewish in Egypt and moved to Europe in her early twenties, fleeing the Suez Crisis.) To her, migration is a positive feedback loop, a key effect and catalyst of nascent Eurabia, and the migrants are the vehicles for transporting poisonous anti-Zionist and anti-American beliefs to Europe.

Littman’s theory informs scads of alt-right blog posts, as well as several self-published books by Norwegian blogger Peder Are Nøstvold Jensen, who writes under the pen name Fjordman. Jensen inspired mass murder in Norway in 2011, when Anders Behring Breivik detonated a fertilizer-based bomb outside the prime minister’s Oslo office, killing eight. Hours later, he shot and killed sixty-nine young adults at a youth camp organized by the country’s labor party (Arbeiderpartiet). In a fifteen-hundred-page manifesto, Breivik cites Jensen’s writing about Eurabia as motivation. Before long, global media coverage of the Breivik attacks had popularized the term. Shortly after the attack, Littman expressed regret that her writing had been involved. On the other hand, Jens Maier, an AfD member of the Bundestag, called Breivik “a victim of the prevailing circumstances.” “Breivik became a mass murderer out of desperation,” he said in 2017.[9]

• • •

Gérôme’s work epitomizes the French academic style of painting. After his studies at the École des Beaux Arts, he toured Egypt and neighboring countries for several months in 1856 and again in 1862. On his return, he began to paint what he claimed to have seen, catering to the public’s appetite for visual insight into the cultures of the Arab world. The images he produced became canonical documents of Orientalism, the name given to the intertwined discourses in the arts and academia through which “European culture gained in strength and identity by setting itself off against the Orient as a sort of surrogate and even underground self,” as Edward Said puts it in his groundbreaking book on the subject. In fact, the cover of his Orientalism bears another of Gérôme’s paintings, The Snake Charmer, also owned by the Clark.

Typically, Orientalist paintings claimed to document the Eastern world (photography was too young to fill that function), using the restrained brushstrokes of academic realism to produce the effect of objectivity. They thus served as visual aids to anchor and reproduce the exoticizing fantasy Europeans had about what the nations of the East and their residents were like. Gérôme’s exacting style allowed The Slave Market to masquerade as documentation. His paintings, despite being mere illustrations, played a deceptive evidentiary role: he had been there and seen with his own eyes, and had the marvelous ability to render these delicious visions on canvas! “All aspects of the Orient are there,” wrote critic Émile-Louis Galichon about another of Gérôme’s paintings in 1863, rattling off traits that list the qualities of the nineteenth-century stereotype: “Its implacable fatalism, its passive submission, its eternal tranquility, its brazen insults and its ruthless cruelty.”

The Slave Market was first exhibited at the Salon of 1867.[10] In his favorable review of the exhibition, critic Maxime Du Camp asserted that the painting had been done “on the spot” in a Cairo slave market during Gérôme’s second trip there in 1862. Sarah Lees, an associate curator at the Clark, writes that Gérôme probably composed The Slave Market in his studio in France in 1866, mining his imagination to update a very similar composition he had made in 1857. In that earlier painting, the man examining the slave’s teeth is wearing a classical toga. (The painting also prefigures Gérôme’s 1884 painting, A Roman Slave Market.) The events depicted were possibly based on the Orientalist writer Gérard de Nerval’s description of slave markets he claimed to have seen on his own travels. The details were probably borrowed from a variety of sketches, conglomerating details from many distant locales into a singular representation of the entire Arab world as seen through the eyes of a Frenchman.[11] Moreover, Gérôme’s contemporary Edward Strahan noted in 1881 that the woman in the painting so resembled Cleopatra in Gérôme’s Cleopatra and Caesar (also painted in 1866) that Gérôme may have used the same Parisian figure model. As Lees puts it, this provides “a certain irony for the informed viewer in seeing the same figure as both queen and slave. ... Despite the difference in their social status, however, their sexual status is nearly equivalent, as the figure in Cleopatra and Caesar is only marginally more clothed.”

• • •

Orientalist painters complemented their tight brushwork with a liberal dose of sensory detail. The Slave Market brought the imagined Orient closer by making its exotic sensations accessible from Europe; at the same time, it held those colonized at an unbridgeable moral distance by chronicling their purported cruelty. The details turned their characters into depersonalized avatars of their race, aesthetic objects for consumption, mannequins for their exoticized clothing and behavior. The painting “guarantee[s] through sober ‘objectivity’ the unassailable Otherness of the characters,” as art historian Linda Nochlin puts it. Meanwhile it affords its viewer the vicarious pleasure of the characters’ less sophisticated indulgences: “the male viewer of the 19th century was invited sexually to identify himself with, yet morally to distance himself from, his Oriental counterparts,” she writes. To her, Gérôme seems to be saying, “‘I am merely taking careful note of the fact that the less enlightened races indulge in the trade in naked women—but isn’t it arousing!’”

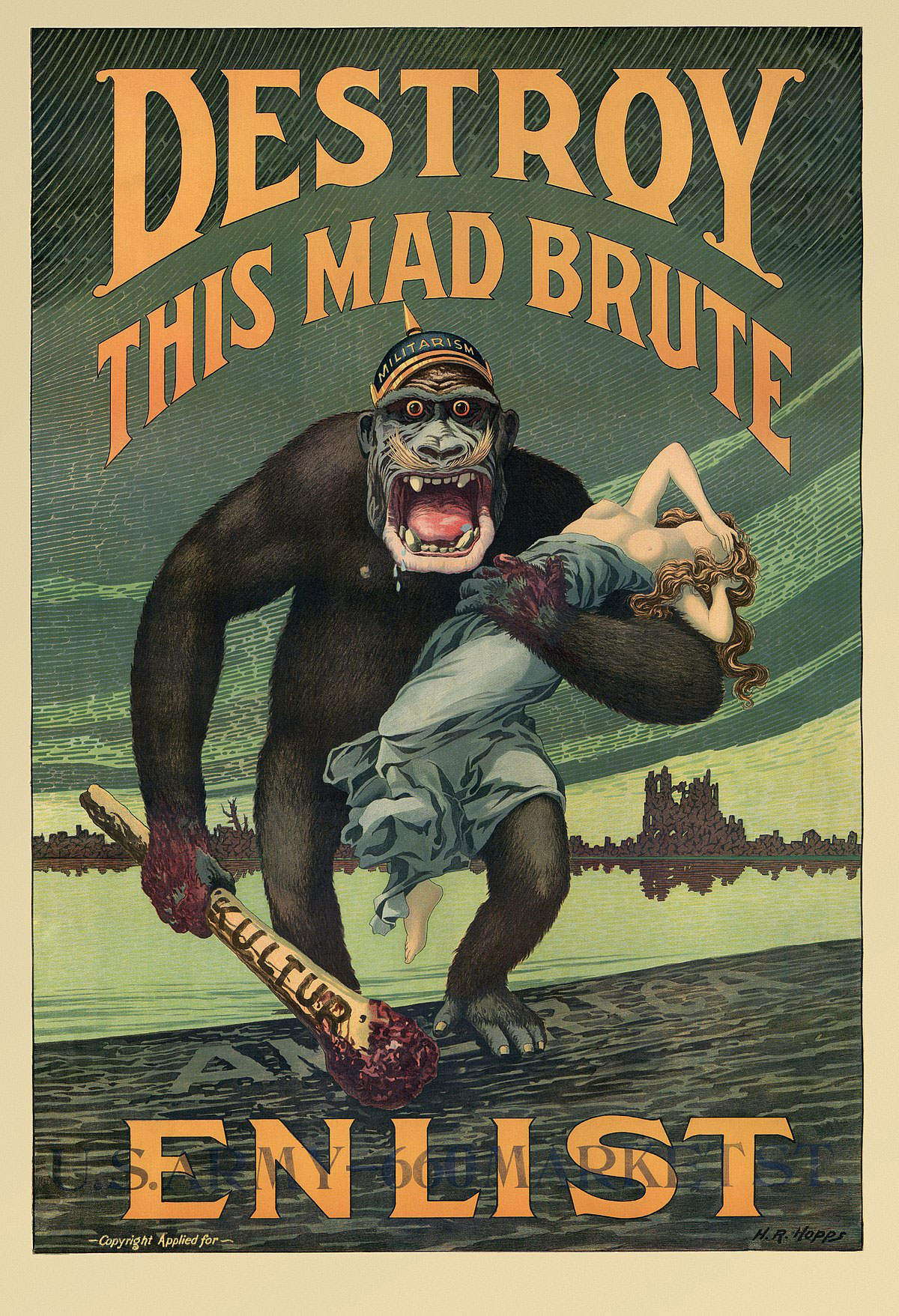

Oddly, the woman in the painting is noticeably detached from her surroundings: her shoulders are relaxed, and she leans on one hip like a classical nude. Gérôme decided to prioritize producing a delicious object for aesthetic appreciation over a suffering character deserving of empathy, a choice that seems like it should undermine the AfD’s point. Nonetheless, the AfD uses the same image that bemused and aroused a fascinated nineteenth-century audience to solicit fear. Orientalism characteristically infantilized those it depicted to make them seem fascinating and able to benefit from the influence of colonizing powers; today’s far right registers the very same characters as menacing, while deploying the woman’s body to make white Germans angry and protective. Posters alleging sexual violence have of course long served as propaganda in conflicts between Western countries: an American World War I poster depicted Germany as a gaping, drooling gorilla gripping a club with the word “Kultur” in one hand and a recoiling half-naked woman in the other; several countries used illustrated allegations of rape against the Soviet Army. Naked women transform readily into the wives or daughters of male viewers. The AfD poster urges its would-be supporters: Worry about your women!

Gérôme’s painting affirmed the nineteenth-century European viewer’s identity, while providing assurance that the lewd behavior depicted was safely at bay. Framed by its new caption, the painting depicts a possible future rather than a present elsewhere. “We did it because the picture shows clearly where the multicultural society could lead,” said AfD spokesperson Ronald Gläser. This shift dislodges the painting’s events from their spatiotemporal home in a fantasy version of colonial North Africa, relocating the scene from a past “there” to a future “here.”[12]

The poster asserts that everyone who migrated from any part of the contemporary Arab world is reducible to a nineteenth-century caricature. But conversely, it claims to reflect the contemporary world by applying twenty-first-century understandings of identity to figments of Gérôme’s imagination. The AfD means for this woman to be perceived as a white Eurabia resident of European descent. According to Maxime Du Camp, the character represented in the painting was meant to be from Abyssinia, a historical region of East Africa. It is unclear whether Du Camp, who often used Gérôme’s paintings as a springboard for his own dubious Orientalist musings, can be trusted to know the painter’s intentions. Nonetheless, a straightforward attempt to ascribe European ethnicity or the twenty-first-century conception of whiteness to the figure is dubious at best.

• • •

Like the Gérôme poster, previous AfD campaign materials have often used white female bodies to incite racist sentiment. A poster from the 2017 national parliamentary campaign features an image of a reclining pregnant woman, cropped so as to emphasize her broad smile and round belly. “New Germans?” read the caption, “We will make them ourselves.” Another poster from the same campaign shows two bikini-clad young women walking away from the camera toward the ocean. “Burkas?” it reads, “We prefer bikinis.”[13] Other AfD campaigns have often directly attempted to make white women scared for their safety. In 2017, an AfD youth group near Bad-Kreuznach in Rhineland-Palatinate, a quite liberal state in the west, handed out pepper spray to teenage girls and was overheard instructing them to use it “to protect yourself against North Africans.” In advance of the September 2019 state elections, the Saxony division of the AfD circulated a design for a poster that depicted a cowering naked woman with her hands cuffed to a radiator. A silhouetted arm holds a sabre. “Pepper spray doesn’t always help,” reads the copy.[14]

The party also made use of several other old paintings in its May campaign, which was titled “Learning from Europe’s History.”[15] A spokesperson claimed that the campaign called for the defense of “common values” evidenced by “numerous motifs,” the phrasing suggesting that the AfD wants to use old art as proof of the timelessness of their agenda. Appealing to the authority of old art to legitimize current racist agendas is not a new strategy. The racial scientists of the nineteenth century leaned on the aesthetic merits of the Apollo Belvedere for credibility in asserting the biological superiority of the white man. The sculpture served as the paragon of whiteness in Josiah C. Nott and George R. Gliddon’s infamous Types of Mankind (1854). The use of high culture material is not new to contemporary far-right populist movements, either.[16] Even so, the AfD takes a peculiar, ironic approach to these images, which are used as decontextualized pretty pictures; the captions demonstrate total disinterest in the paintings’ historical meanings.[17]

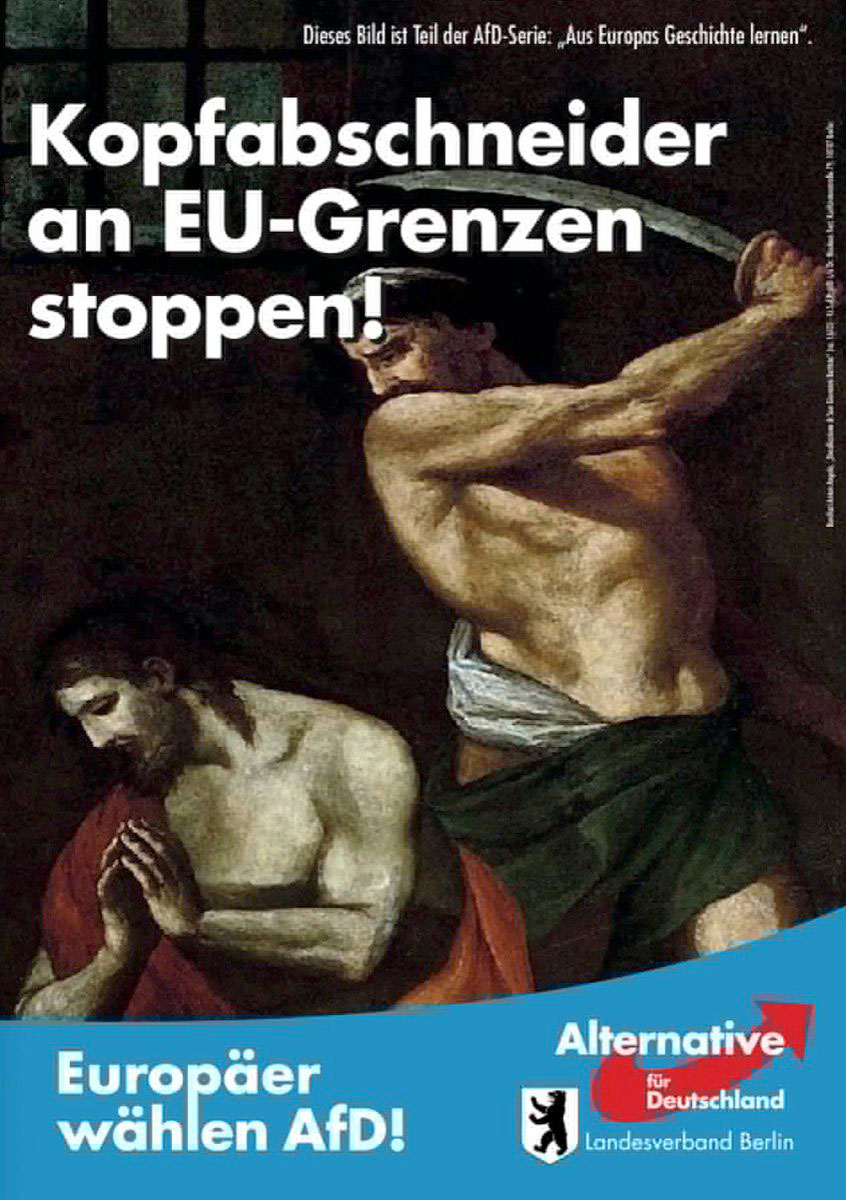

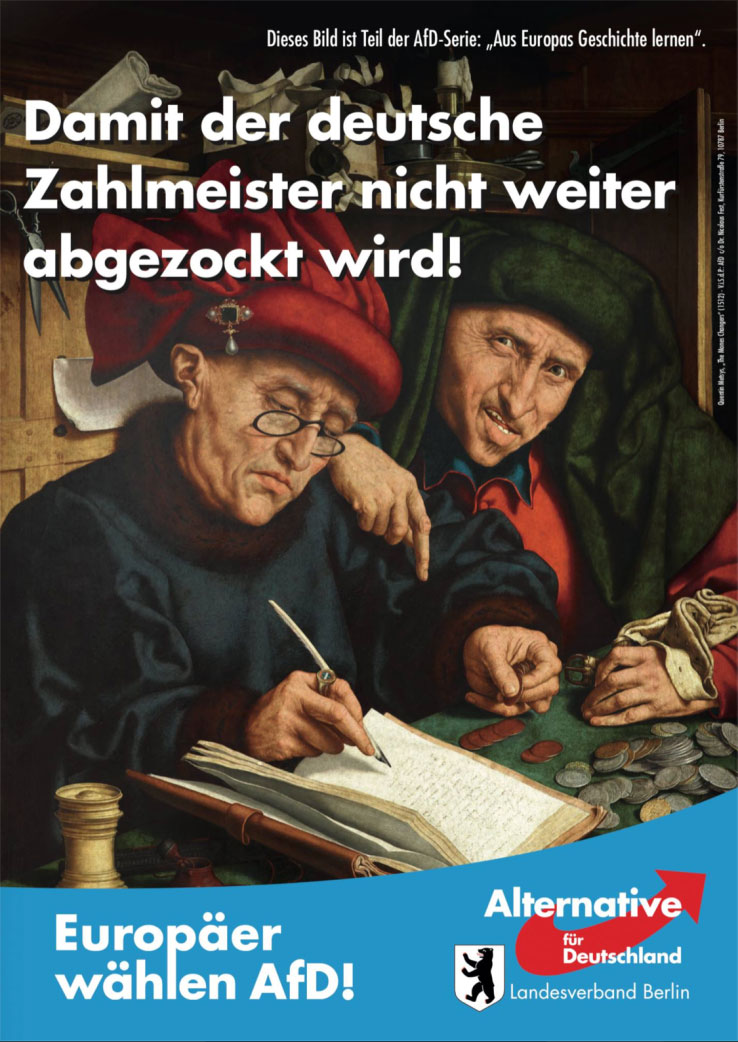

Nor do the paintings have a lot in common. Two sixteenth-century portraits of men made out of plants by the Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo are used to caricature Green Party members. The caption of a little-known seventeenth-century rendering of the decapitation of St. John the Baptist represents migrants as violent barbarians who should be barred from the EU. A sixteenth-century Flemish painting of two men handling money bears a complaint about Germany getting fiscally ripped off.[18] The indifference to context is almost mocking in its obliviousness.[19] The reality is that the AfD does not need historically accurate arguments or cultural credibility derived from bourgeois art objects to provoke fear.

We can expect atrociousness from the far right. Seeing the party’s numbers rise despite (or because of) its vicious visual culture is terrifying. It is no less scary to see its rhetoric seep across party lines and get soaked up and deployed by purportedly moderate parties. In September, the German president-elect of the European Commission announced plans for a rebrand that included changing the title of the EU commissioner of migration to commissioner for “protecting our European way of life.” The president-elect, Ursula von der Leyen, is a member of the Christian Democratic Union, the center-right party of Angela Merkel, who herself has condemned far-right xenophobia. Von der Leyen’s phrasing recalls Littman’s paranoia and echoes Jensen’s word choice in his book Defeating Eurabia: “The crucial point is to stress that Islam cannot be reformed nor reconciled with our way of life.” Illustrations of pseudo-Orientalist panregional dystopias become especially dangerous when their logics leak into the casual rhetoric of the center.

- See Nicholas Kulish and Melissa Eddy, “German Elites Drawn to Anti-Euro Party, Spelling Trouble for Merkel,” The New York Times, 14 April 2013. The Gérôme ad, appealing to a pan-European sentiment, is perhaps ironic considering the AfD’s origins as a soft Euroskeptic party primarily advocating against further integration.

- The original reads: “Damit aus Europa kein ‘Eurabien’ wird!” The AfD also distributed an alternative version of the poster with the caption “Silvesternacht, Köln, 2015/16,” which references the 2015 New Year’s Eve incidents in Cologne. According to the BBC, about eighty women reported being sexually harassed or mugged (and one woman raped) by men “of Arab or North African appearance,” according to the city police chief.

- In March, prior to the poster’s debut, the Berlin faction of the party announced it would offer a reward of five hundred euros for information leading to the “seizure” of anyone who vandalized forthcoming campaign material. “Whoever damages posters must be punished,” said party official Georg Pazderski. The AfD has historically had major issues with vandalism. The party claimed that in the 2017 national election, nearly half of their 33,000 small posters were ruined or removed, and that vandals had destroyed 141 larger posters on average 2.8 times each. Replacing the damaged posters supposedly required four hundred hours of work on the part of AfD’s campaign team. Der Tagesspiegel reported that in 2014, Bernd Lucke’s own wife and daughter were responsible for replacing approximately forty posters each morning and evening in his hometown in Saxony. In 2017, there was a violent conflict in Berlin between two men putting up AfD posters and a member of the public.

- Gläser is here implying that there has been an increase in illegal border crossings. In fact, the number of non-EU citizens found to be illegally present in Germany has been dropping: 134,100 people were found in 2018, compared to 376,400 in 2015.

- The portmanteau follows the form of the term “Eurafrica,” which refers to the European imperialist fantasy of a merger between Europe and Africa, an idea that became popular during the period just after World War I when many Europeans were dreaming up fanciful panregional solutions to geopolitical conflict. Though some have described Littman as a historian, which might imply academic status, she never completed her undergraduate studies and has never taught at any academic institution. Nonetheless, she gave testimony at a US Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing in 1997, and spoke before the Congressional Human Rights Caucus on two occasions. Before publishing her book on Eurabia, Littman spoke about the threat of cultural subordination, which she calls dhimmitude, at Brown, Georgetown, and Yale. She also spoke following the publication of Eurabia at Columbia in 2005. She has published several books, including Eurabia, with Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, which is located in New Jersey.

- Among the weak examples she cites as evidence of the takeover of European culture due to the resolutions of the Euro-Arab Dialogue: the inclusion of information about Islam in textbooks; the hiring of university faculty whose research deals with the Arab world; shifts in museums’ holdings; and increases in the translation and publication of “Islamic works.”

- The committee was active at least until 1985, when the UN reported that it had been represented at a meeting of NGOs on “The Question of Palestine.”

- Littman refers to EU attitudes toward terrorist attacks in the first years of the 2000s in both countries as “victim blaming,” and suggests that attitudes toward Israeli militancy may be “the secret schadenfreude fulfillment of an interrupted Holocaust.” Meanwhile, the AfD has repeatedly advocated for releasing German citizens from guilt about the country’s past, and for reclaiming German words that currently connote support for the Third Reich.

- Maier’s original words: “Ein Opfer der herrschenden Umstände. ... Breivik ist aus Verzweiflung heraus zum Massenmörder geworden.”

- It passed from owner to owner until it was bought in 1930 by Robert Sterling Clark, an heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune, whose collection became the Clark Art Institute in 1955.

- Art historian Linda Nochlin notes that at the time, it was presumed that artists of stature had “more or less unlimited access to the bodies of the women who worked for them as models,” a point that makes Gérôme seem slightly hypocritical when considered in the context of a painting meant to cast those who sell women as slaves in a morally disapproving light. According to Nochlin, when Manet several years later painted white Frenchmen negotiating with prostitutes in Paris, he was rejected and reprimanded for obscenity by the same Salon that had adored The Slave Market.

- The AfD suggests that there is still time to avert Europe’s transformation; canonical Eurabia believers seem to disagree. For Littman, the true consequences were yet to come as of 2005, but the process had been irrevocably set in motion due to how thoroughly institutions and minds had been permeated by ideas of cooperation: “It is a project that was conceived, planned and pursued consistently through immigration policy, propaganda, church support, economic associations and aid, cultural, media and academic collaboration. Generations grew up within this political framework; they were educated and conditioned to support it and go along with it.” For Fjordman, writing in 2006 prior to the dissemination of Defeating Eurabia in 2008, Eurabia had already arrived, and white Europeans have been brainwashed into not noticing.

- Another 2017 poster featured a baby pig in a grassy field with the caption “Islam? It doesn’t work with our cuisine.” The ad was later cancelled, not due to its Islamophobic message, but rather because AfD politician Alexander Gauland was concerned that viewers would sympathize with the very cute animal: “The poster campaigns for the piglet, not against Islam, so away with it.”

- The original reads: “Pfefferspray hilft nicht immer.” Party officials clarified that they themselves did not stage the photograph. “The photo comes from an online picture service,” said an AFD spokesperson.

- The German reads: “Aus europas Geschichte lernen.”

- In 2016, a white supremacist group called Identity Evropa targeted US college campuses with a poster campaign featuring the Apollo Belvedere and other classical and Renaissance sculptures with captions such as “Protect Your Heritage.” And of course, numerous white nationalist groups and pundits have been known to coopt medieval visual culture to restore colonialist fantasies about white European cultural superiority and construct a visual definition of their Ideal Man.

- The posters were apparently designed primarily by freelance advertising professional and novelist Thor Kunkel. The AfD hired Kunkel to work on the May election campaign; he had also designed the posters for 2017. Kunkel is not technically a member of the AfD, and—though clearly an unsavory and Islamophobic figure—takes care to assert his independence from the party. Additionally, in 2017 the AfD became a client of Harris Media, a Texas-based ad agency that works for clients including the UK Independence Party, Netanyahu’s Likud Party, Newt Gingrich, and Mitch McConnell. According to Der Spiegel, Harris Media has helped the AfD become more insidious by enabling them to circumnavigate German subsidiaries of social media firms, putting them directly in touch with strategic contacts in Silicon Valley. They have also suggested making AfD’s logo smaller on publicity material to alleviate would-be supporters’ anxieties about identifying with the party by making the AfD seem less like other far-right groups, which have typically emphasized their symbols in their visual material.

- The caption uses the term Zahlmeister, which literally translates as “paymaster.” The term, which originally referred to professional intermediaries appointed to manage the distribution of money (an occupation that no longer exists), has also been used to lamentingly describe Germany’s role keeping accounts for the EU, especially during the financial rockiness of the latter part of the first decade of the century. The poster seems to be a rekindling of AfD’s initial frustration with economic pressure from other European countries.

- Though brought into public view in the wake of the Breivik attacks, Eurabia is a relatively niche conspiracy theory. Part of the poster’s power derives from its ability to communicate exactly what the term means without added explanation, implying that the threat is common knowledge.

Lily Scherlis is a writer, artist, and PhD student in English at the University of Chicago. She recently moved to Chicago from Berlin. She has contributed to Harvard Magazine and The Harvard Advocate.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.