American Photographs: The Road

Two Soviet writers’ travelogue of their journey through Depression-era America, translated and introduced by Erika Wolf

Ilya Ilf & Evgeny Petrov

In 1935, the collaborative satirical writers Ilya Ilf (1897–1937) and Evgeny Petrov (1903–1942) traveled to the United States from the Soviet Union on assignment as special correspondents for the newspaper Pravda. Shortly after their arrival in New York aboard the French luxury liner Normandie, they purchased a Ford automobile and embarked upon a ten-week road trip to California and back. Ilf and Petrov visited America as literary tourists, stopping at major attractions, staying in tourist motels, consulting with AAA for travel advice, and relying upon Russian-speaking tour guides to smooth their way. Like a good tourist, Ilf extensively recorded his trip with his Leica camera. Shortly after their return to the Soviet Union, the popular illustrated news magazine Ogonek—a Soviet analogue to Time magazine—published a series of illustrated articles entitled “American Photographs.”[1] Individual installments featured such thematic topics as the road, the small town, Native Americans, Hollywood (where they spent two weeks writing a screenplay for Lewis Milestone), advertising, African-Americans, and New York City. I first learned of Ilf’s photographs from a review of “American Photographs” written by Alexander Rodchenko in 1936. I was intrigued by the images reproduced with the review—shots of rural highways and road signs that brought to mind the Depression-era images of Walker Evans. Curiously, the title of this series is identical to Evans’s American Photographs, a landmark book in the history of photography published by the Museum of Modern Art in 1938.

Ilf and Petrov’s journey was also the subject of their final major collaborative project, Odnoetazhnaia Amerika [“Single-Storied America”].[2] An account of their road trip through the United States, the book expands and incorporates into the travel narrative some of the topical themes first developed in “American Photographs.” The first edition of the book was supposed to feature Ilf’s photographs, but for reasons that remain unknown it was published without any illustrations. Given the political climate in the Soviet Union in 1937, with the onset of the Terror, it is surprising that even an unillustrated version of a book that lovingly satirizes the United States was published. Sadly, both authors died within the next decade. During the trip, Ilf developed his first symptoms of tuberculosis; he passed away just as the first edition of the book appeared in print in 1937. Petrov perished in a plane crash while working as a war correspondent in 1942.

—Erika Wolf

On the fifth day of a journey across the Atlantic Ocean, we saw the gigantic buildings of New York. Before us was America. But when we had been in New York for a week and, as it seemed to us, we began to understand America, we were quite unexpectedly told that New York is not at all America. They told us that New York is a bridge between Europe and America, and that we were still situated on the bridge. Then we went to Washington, being steadfastly convinced that the capital of the United States is indisputably America. We spent a day there, and by evening we managed to fall in love with this purely American city. However, on that very same evening we were told that Washington was under no circumstances America. They told us that this was a town of governmental bureaucrats and that America was something quite different. Perplexed, we traveled to Hartford, a city in the state of Connecticut, where the great American writer Mark Twain spent his mature years. Much to our horror, the local residents told us in unison that Hartford was also not genuine America. They said that the genuine America was the southern states, while others affirmed that it was the western ones. Several didn’t say anything but vaguely pointed a finger into space. We then decided to work according to a plan: to drive around the entire country in an automobile, to traverse it from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific and to return along a different route, along the Gulf of Mexico, calculating that indeed somewhere we would be sure to find America. We returned to New York, purchased a Ford (transportation in one’s own automobile is the least expensive means of travel in the United States), insured it and ourselves, and on a chilly November morning we left New York for America.

For the course of two months before our eyes were roads of white concrete, black asphalt, or gray granular gravel and saturated with heavy oil.

At first we were enraptured by these magnificent roads, then we got used to them and then we even got angry, if sometimes due to the repair of a route, we happened to make a small detour on some bumpy bit of old, pock-marked road.

The roads are one of the most splendid phenomena of American life. By December of last year in the United States, there were one and a half million so-called highways—big roads along which autobuses travel day and night according to fixed schedules.

In the east of the country, where automobile traffic is especially heavy, three-lane iron-reinforced concrete roads are prevalent, thousands of miles ruled out with thick white lines. Two lanes for traffic, a middle lane for passing.

The closer you get to a city, the wider the road becomes. Its lines run out from under the wheels of the automobile multiplying in number every minute, like railway tracks that increase tenfold upon nearing the proximity of a big train station.

This photograph [above] shows the approach to the city of San Diego, California. This state is proud of its roads and in advertising prospectuses it never fails to mention them. However, we found such roads on the outskirts of all more or less large American cities.

Sometimes, especially in the mountains or national parks, we were suddenly enraptured by the emerging landscapes. Each turn of the road obligingly opened to us newer and newer perspectives of a beautiful view. The road, furthermore, led us from one landscape to another. It demonstrated nature to the traveler with the skill of an artist displaying pictures to a visitor at an exhibition.

This type of road has its own special designation—scenic road—painterly road. Such roads are laid out with a special aim: to show nature to the traveler, so that it will not fall to his lot to scramble up cliffs in search of a proper observation point, so that the necessary quantity of emotion may be obtained without getting out of the automobile.

Without getting out of the car, the traveler may similarly obtain the necessary quantity of gasoline at the service stations, which stand in the thousands along American roads.

The tank is full. It’s possible to quietly travel onward. However, the gentleman in the striped service cap and leather bowtie does not let the traveler go. The famous American service begins. The man from the gas station opens the car’s hood, checks the oil and water. Then he checks the air pressure in the tires. However, he does not consider his mission complete with this. He wipes the windscreen of the car with a cloth. If the glass is very dirty, he wipes it with a special powder. And then, everything is in order. But now, softened by the service, the traveler himself no longer wants to depart. It seems to him that the hatch of the automobile is not slamming shut tightly enough.

Benevolently smiling, the gentleman extracts a tool from his hind pocket and in two minutes the door is in order! It’s possible to go. But he doesn’t want to. He wants service, a little more of this wonderful and, more importantly, free service. The traveler asks what is the best way to get to a nearby town. In response to this, he receives a first-class map of the state, upon which the man from the gas station sketches the further route of the motorist. On the reverse side of the map are the names of hotels and tourist homes. Also listed are noteworthy places that will be encountered on the road. And all of this is a free bonus for purchasing gasoline. With regret, the traveler abandons the hospitable station attendant, comforting himself only when after 100 miles the gasoline runs low, and when at that very minute it runs low, a new gas station appears without fail on the road, where he is met by the same hospitable man in a striped cap and leather bowtie.

After every thousand miles, it is necessary to change the oil in the motor and to lubricate the engine. This costs $1.50 dollars. A painful moment!

“It seems that we recently changed the oil,” says the traveler with sadness.

The usual gentleman with the leather bowtie raises the car on a special stand and suggests that the traveler take a stroll in town. In exactly an hour, the car is again on the ground, more truly on the asphalt. Now it is possible to quietly drive another thousand miles.

A foreigner, not having mastered the English language, may venture onto the American road with an easy spirit. He does not risk getting lost. On these roads it is possible even for a child or a deaf mute to drive independently.

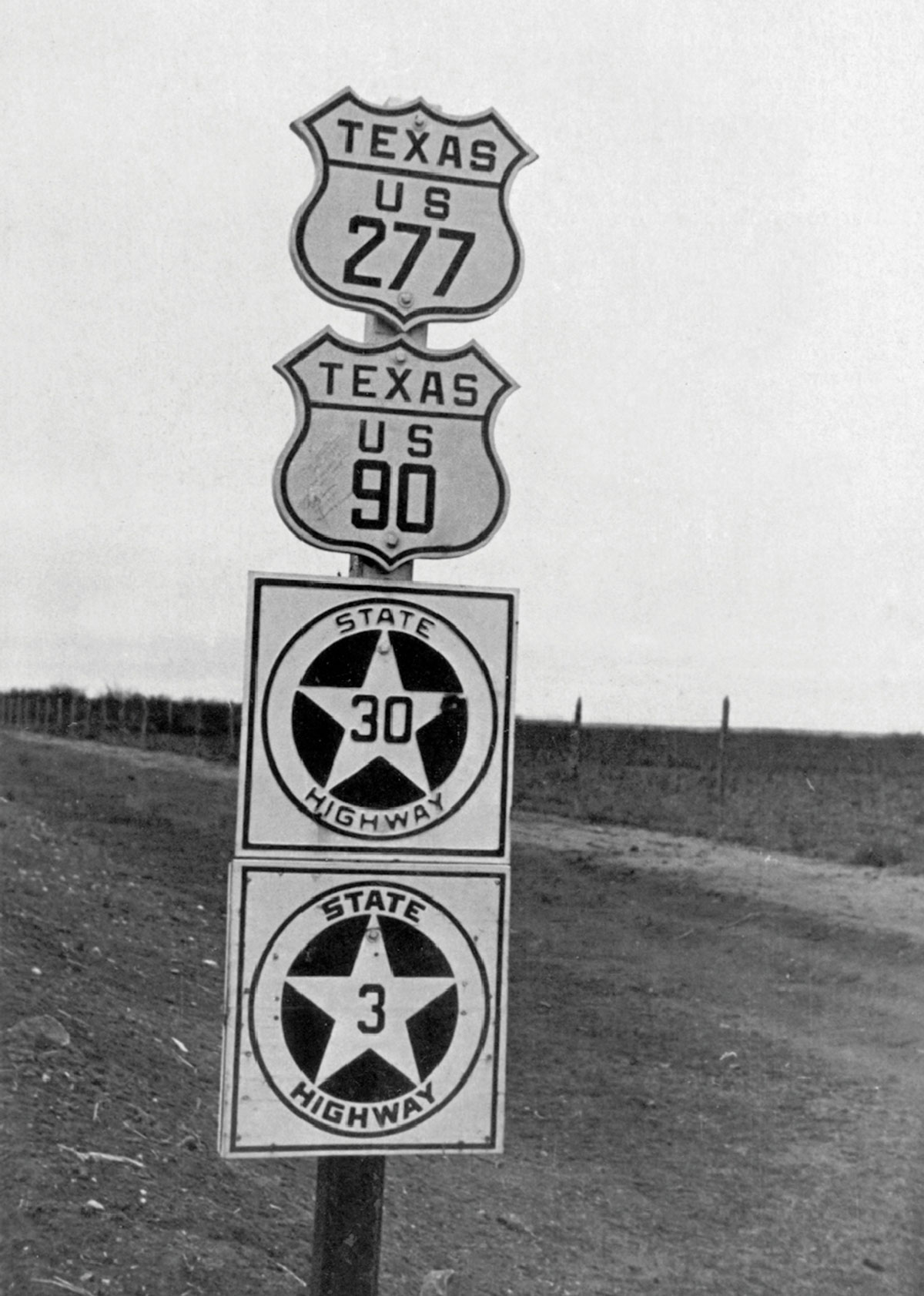

The roads are carefully numbered. The numbers are encountered so often that to get lost on a route is simply impossible.

Sometimes two roads come together for a while as one. Then two numbers appear on the pole—the number of the federal road above, and the number of the state road below it.

Sometimes five, seven, or even ten roads come together. Then the quantity of numbers grows along with the pole to which they are attached.

There are many different signs on the road. They are placed close to the ground on the right side, so that they always fall into the driver’s field of vision. They are never tentative and do not require any decipherment. In America you never encounter anything like a mysterious blue triangle in a red square, a sign that it is possible to spend hours racking one’s brain upon trying to figure out the meaning.

The arrow shown in the photograph marks a turn to the left. It is equipped with small circular mirrors that reflect the light of automobile headlamps at night. In this way the sign is self-illuminating. The big black inscription on the yellow ground (it is the most noticeable color) signifies “Slow!” In a similar manner, simply and clearly, are composed the road signs “School Zone,” “Stop,” “Danger,” “Narrow Bridge,” “Speed Limit 15 MPH,” or “Pothole in 300 Feet.” You can rest assured that in exactly 300 feet there will be a pothole. However, such notices appear just as rarely as do potholes.

At the intersections of roads stand columns with thick wooden arrows that indicate directions. On them are the names of towns and the number of miles to these towns.

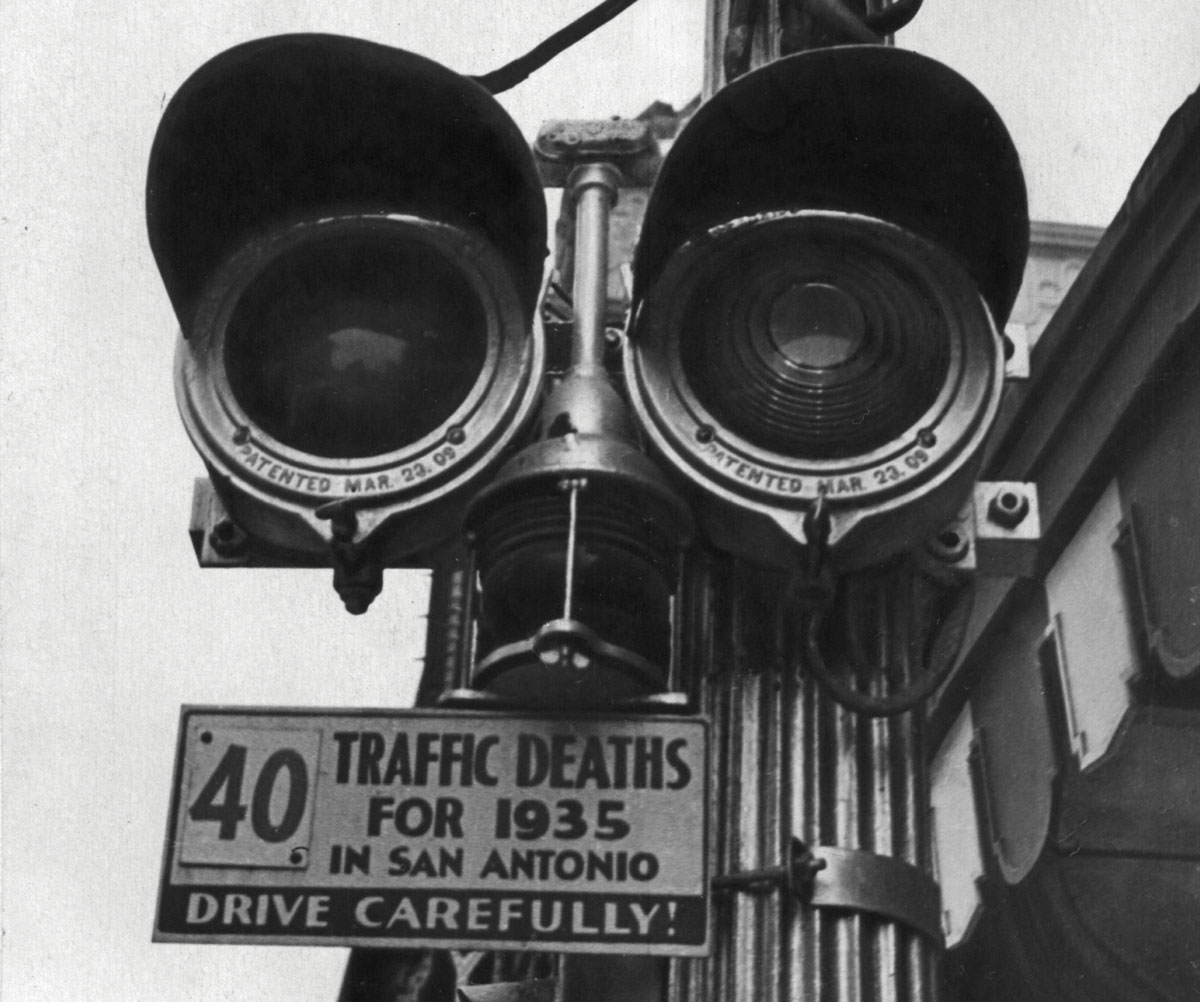

In the town of San Antonio, Texas, posters hang under the traffic lights at each intersection: “40 traffic deaths for 1935 in San Antonio. Drive carefully!” Sometimes it is possible to observe a rather dark humor in inscriptions of this sort. In the east, we saw along a road the sign: “Drive carefully. Cemetery after the bend.”

By the way, about cemeteries...

Here is the type of cemetery that is encountered most often in America. It is an automobile cemetery.

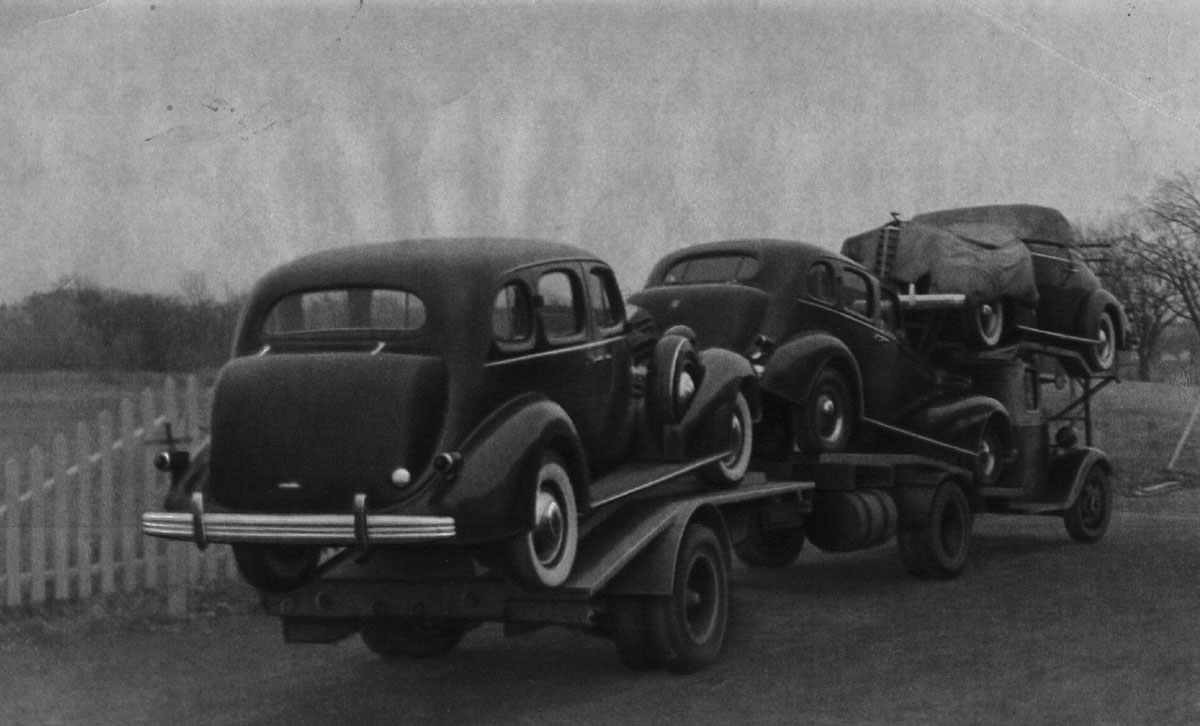

Taking the place of the old automobiles leaving service are new ones.

This quickly moving, strange-at-first-glance contraption [above] turns out to be a truck with a trailer on which are placed automobiles fresh from the factory. One truck simultaneously carries three or four cars. And this turns out to be cheaper than transporting automobiles by railroad.

In general, a railroad trip in America is an expensive thing. A passenger bus is twice as cheap.

At any time of the day, at any time of the year, on any road, passenger buses with sleeping facilities furiously race across America. They go according to schedule, with a speed of 70 to 80 kilometers an hour.

When at night you see a heavy and menacing automobile flying across the desert, you are involuntarily reminded of Bret Harte’s postal diligences, steered by desperate coachmen.

This picture [above] should be captioned as follows: “Here, this is America!”

And, indeed, when you close your eyes and try to rekindle memories of this country where you spent four months, you don’t imagine yourself in Washington with its gardens, columns, and full collection of monuments, nor in New York with its skyscrapers and its poor and rich, nor in San Francisco with its steep streets and suspension bridges, nor in the mountains, factories, or canyons, but at such an intersection of two roads and a gasoline station against a ground of wires and advertising signs.

Translated by Erika Wolf

Photos by Ilya Ilf. Reproduction of photographs courtesy Sasha Ilf.

Ilf and Petrov’s American Road Trip, the book-version of Ilf and Petrov’s essay, is available here.

See press on Ilf and Petrov in Radio Free Europe.

- Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov, “Amerikanskie fotografii,” Ogonek, 1936, nos. 11–17, 19–23. “The Road,” the segment of American Photographs presented below, was originally published in Ogonek, 1936, no. 11, pages 2–6.

- Odnoetazhnaia Amerika (Moscow: Khudzhestvennaia literatura, 1937). The book was published in the United States as Little Golden America (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1937), a title calculated to build upon the American success of their novel The Little Golden Calf (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1932).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.