The Law of Averages 1: Normman and Norma

Looking for Mr. and Mrs. America

Dahlia S. Cambers

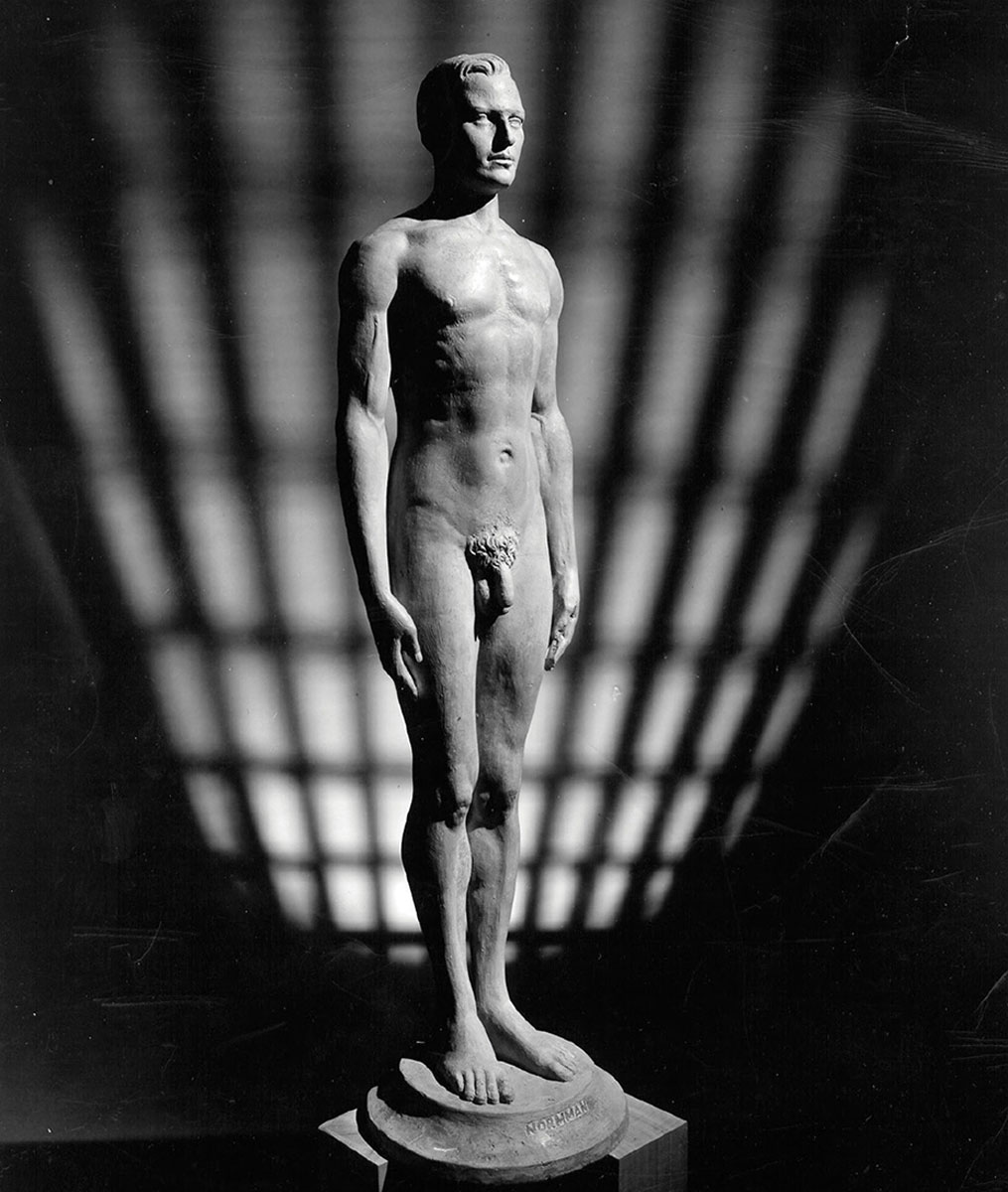

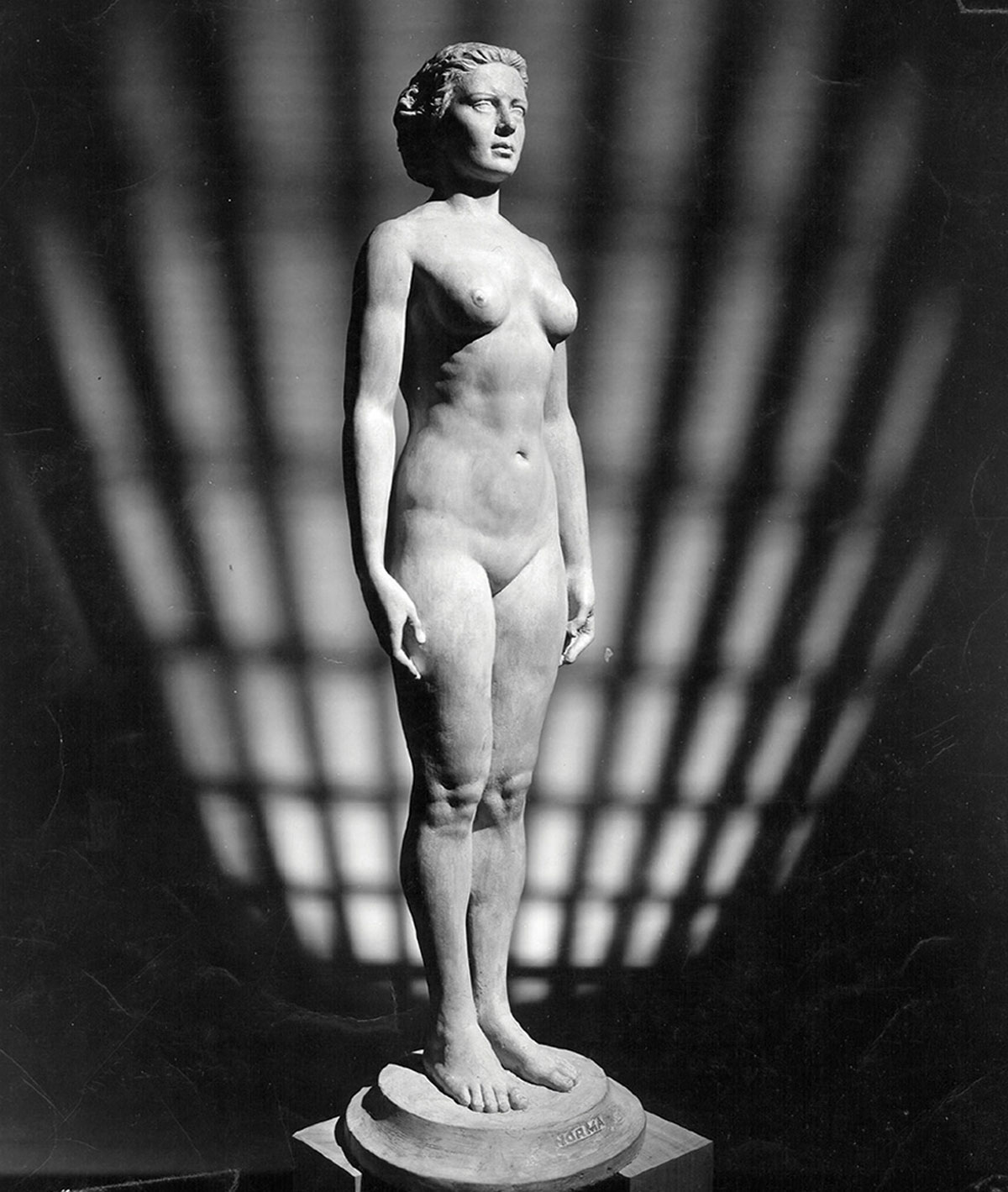

These statues, Normman and Norma, are the 1943 work of artist Abram Belskie and obstetrician-gynecologist Robert Latou Dickinson. Dickinson, a major contributor to the study of female sexuality, former vice-president of Planned Parenthood, and president of the Euthanasia Society from 1946 to his death, was well-known for his interest in depicting female and embryonic anatomy in sculptural form; his typical gynecological examination included anywhere from 5 to 61 drawings of each patient, drawings which were then used to create three-dimensional teaching aids—anatomical mannequins so expressive Dickinson was dubbed the “Rodin of Obstetrics.”[1] Carved of white alabaster, Norma and Normman were based on the measurements of 15,000 men and women between the ages of 21 and 25 compiled from a variety of sources, but decidedly, those of a white racial group. Anthropometric data had long been collected, first by the fields of phrenology, anthropology, and eugenics, and then by the US garment industry (in efforts to nail down standardized sizes), life insurance companies, and the medical establishment. (The first tables corresponding height and weight proportions were published between 1900–1920).

Dickinson intended the sculptures to showcase the improving health of American stock. Norma, whose figure received a disproportionate amount of attention in the press, was purportedly taller, more athletic, thicker-waisted (healthy evidence that she didn’t wear a corset) and had better posture than her grandmother, shorter and more busty than the high fashion models of the day, and had hips slenderer than those of the Venus de Milo.[2] All in all, her figure bode well for the future of America, provided she chose a proper mate: “Norma’s Husband Better Be Good. Evolution Outlook Bright if Model Girl Weds Wisely” ran the headline of a 1945 article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer.[3]

When the Cleveland Health Museum purchased the statues in 1945, the museum decided to sponsor a contest to find an Ohio woman whose body matched the dimensions of Norma. There was no comparable effort to find a Normman. Offering a $100 US War Bond and the dubious title of “Norma, Typical Woman,” the call for entries in the Cleveland Plain Dealer advised women on how to measure their hips, bust, neck width, wrist circumference, etc. Perhaps indicative of the elusiveness of true normality, only a minute percentage of the 3,863 entries approached the “average” dimensions of the statue, although the prize eventually went to a 23-year-old theater cashier.[4]

- “After Office Hours: The R. L. Dickinson Collection of Sculptured Teaching Models of the Cleveland Museum of Health,” Obstetrics and Gynecology 14.3 (September 1959), pp. 404–410.

- Harry L. Shapiro, “Americans Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow,” Natural History, publication of the American Museum of Natural History (June 1945).

- Josephine Robertson, “Norma’s Husband Better Be Good,” Cleveland Plain Dealer 16 September 1945. Cited in Julian B. Carter, “White Love: Sexual Normality and the Future of the Race, 1890–1940,” [unpublished dissertation, Stanford University, 1999], p. 10.

- This article is indebted to David Serlin and also to Jacqueline Urla and Alan C. Swedlund’s “The Anthropometry of Barbie: Unsettling Ideals of the Feminine Body in Popular Culture,” available in Londa Schienbinger, ed., Feminism and the Body (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 397–428.

Dahlia S. Cambers is an independent scholar based in Columbus, Ohio.