Stumped

What remains of the Thousand-Year Reich?

Walead Beshty and Eric Schwab

Of course he suspects why we’re here, where we’ve just been. He lives here, he’s old enough, maybe he knows something. I ask in German if he knows anything about that concrete hulk back there, den Betonklotz da hinten? Not turning his head to look, he surveys us intently under dark Bismarck eyebrows. His diction is crisp, less a Berliner than a Saxon accent. Ja, der Betonklotz, he responds, hesitantly waving in that direction. They built it in 1942, right in the middle of the war, Hitler and his guys—though actually, he explains, it was built by French prisoners of war.

Gazing straight at it, he begins to narrate. It was an experiment to test the capacity of the ground underneath. You see over there by the bridge, where they’re doing repair work on the S-Bahn tracks? It’s all white sand they’re digging up; all this ground beneath us is Brandenburg sand. That’s why they had to build this massive load-bearing block, diesen Grossbelastungskörper, to see if the ground would hold or how deep it would sink and how fast. It’s actually mushroom-shaped, got a stem sticking as deep into the ground as this apartment building is high. The upper Zylinder here is ten meters in diameter, solid concrete, it must weigh five hundred tons, imagine that. Later on, in the ’50s and ’60s, after the war, engineers from the Technical University came and did more experiments. They installed great long steel tracks down underneath it, and alongside they sunk single cement posts, all for further tests. I’m not sure myself what exactly they were after, he says.

He stares straight past the dark grey mass lurking in the overgrowth. That’s all a long time ago, he continues. You know, even before that, Hitler and his architects wanted to build another concrete mass right in the center of town, in the Tiergarten—a massive plate-shaped foundation slab, wider than the Olympic Stadium, to hold up a gigantic dome that they wanted to build near the Brandenburg Gate. A Volkshalle that would have dwarfed the Reichstag! And then a magnificent boulevard, a Prachtstrasse like the Champs-Elysées, that would run all the way from there right to here, cutting straight through from Kreuzberg to Schöneberg, and from here to Tempelhof airport. You know the grand airport building there? That too was built during the Hitlerzeit. From Tempelhof you can still fly to London and Brussels.

He stretches out his arm to suggest a flying plane, then, with a sweeping gesture, he continues: And right here they planned to erect this huge triumph arch, twice as large as the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, an übergrosse Struktur with four massive concrete pillars holding up four huge archways. Only, before they could start, they wanted to see if this sand underneath us would carry the massive weight. Imagine: each cornerstone was to have inside it a Zylinder as big as this one. The other three were never built, of course. Only this one was finished, and it’s been standing here almost 60 years now. Well, even the T.U. people gave up their experiments in the ’70s. Since then it does nothing but sit there, just like now. It’s too big to tear down, it’s solid concrete, nobody wants to pay for the demolition, you understand? At one point people talked about placing it under protection as an historical site, but nothing ever came of it. Those city building officials still don’t know what to do with this monstrosity, dieses Ungeheuer. Hardly anyone even notices it anymore.

Crazy. Hitler’s architect—Speer was his name—he sat over there in Spandau prison for 20 years, didn’t die until the ’80s. You know, the best view is from above, you can see the whole thing from the roof. Would you like me to take you up there? It’s no problem, I live right here...

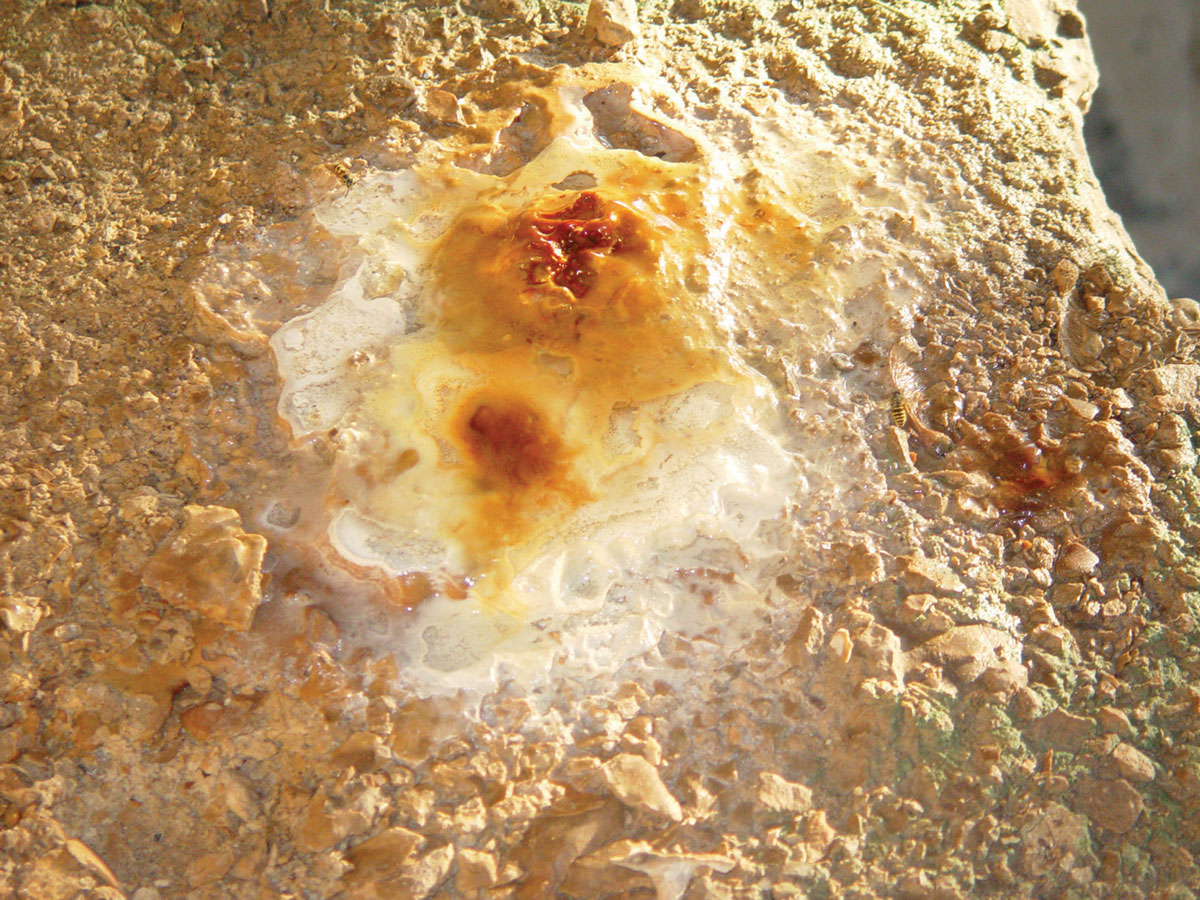

Eager efforts to experience this thing as something more than an abandoned mass of concrete meet with unexpected resistance. If only it offered some trace of Nazi insignia, or some odious corner suggesting atrocious acts—instead of a mute grey lump, not nearly huge enough to overwhelm its surroundings, let alone a curious traveler. If it were ruined, at least it would have ruin-value, the notorious Ruinenwert that so preoccupied Hitler and Speer in their grandiose building plans: to erect edifices with such great masses of stone that their ruins would outlast even the Thousand-Year Reich. But the great arch was never completed—just this one, unfinished remnant, not the kind of thing one might wish to visit and contemplate as a monument or a memorial, not the kind that have proliferated in Berlin especially since the period when this thing and things like it were being built. In a way, its sheer grey obtrusiveness echoes the rows of innumerable smaller blocks recently installed as a Holocaust monument in the center of Berlin. Or Berlin’s few remaining concrete bunkers, which have at least been refitted as scenic lookout towers, or climbing rocks, or movie sets. Though equally indestructible, this block of cement managed to remain altogether useless and ignored—not even a small sign or plaque explains its presence here.

Rejected by history, ignored by tourism, indigestible by nature—what’s left to learn from this silent, stump-shaped lump of concrete? A tree stump, at least, can be made to reveal its own age, its own history—you simply cut it open and count its concentric rings. That tree lived X years, grew Y high, died in year Z—and this was its place in history. But this concrete block? Never finished, never really alive, it never really had its moment in time, its place in history—built to test the possibility of its ever reaching its full size, its sheer bulk instead demonstrated its impossibility, the same impossibility that fated it to remain here: too huge to build, too huge to demolish.

In a passage from W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz, the author ruminates on a recent conversation with the book’s building-obsessed title figure, in which the latter had speculated that only small-scale buildings—forest cottages, bridgekeepers’ huts, scenic pavilions, even tree houses—had the capacity to evoke a sense of peace, whereas in the case of more massive buildings, the larger they grew beyond reasonable human dimensions, the more they seemed to cast a shadow of their own impending destruction, to the point where they could be reasonably understood only as eventual ruins. So Sebald sets off to explore a massive nineteenth-century fortress in the Belgian countryside, expecting to confront the geometric perfection of towering star-shaped fortifications, a ruined emblem of overbearing military rationality. What the author encounters instead is an inscrutable mass of overbaked and wrinkled concrete that, for him, evokes nothing more than a great beached whale, a faceless and formless monstrosity that seems to demand submission even as it defies every effort to comprehend it.[3]

Lurking in Sebald’s incomprehension is really a kind of stubbornness, a refusal either to submit to the brutal necessity of such masses of concrete or else to retreat into a way of understanding them—as ruins or relics conquered by time, superseded by history—that tacitly preserves one’s own sense of superiority. Such mental maneuvers only mimic the polarities of scale and mass these edifices impose: we all are free to deplore such brutal measures until the day we’re relieved to find refuge in them. Perhaps the same stubbornness is what drove Sebald to insist, in On the Natural History of Destruction, that Western civilization had yet to come to grips, even fifty years later, with the devastation inflicted on German cities by Allied bombing in the final years of World War II. Does the victory over unlawful aggression and manifest evil, he wonders, suffice to explain such acts of reciprocal destruction, or does such destruction stand instead as “irrefutable proof that the catastrophes which develop, so to speak, in our hands and seem to break out suddenly are a kind of experiment, anticipating the point at which we shall fall away from what we have thought for so long to be our autonomous history and sink back [zurücksinken] into the history of nature?”[4]

A stillborn monstrosity of human ambition. Conceived to commemorate the climax of an era that aimed to last a millennium but destroyed itself in hardly more than a decade. Now just another beached leviathan, slowly sinking back into the sands of timeless nature—so maybe the only remaining question is, will it disappear altogether before the present historical era, of industry and capitalism and democracy, of cities and civilization and autonomy, itself sinks back into the nature from whence it sprang?

In the end, of course, most of Speer’s grand plans for Berlin were realized only in miniature as architectural models. Then again, in retrospect it seems clear that these plans and models were never really meant to have a life-sized version. Speer himself recognized that such buildings would be not only bigger than anything yet built but, in effect, beyond all dimension, überdimensional. Indeed, as Speer notes sardonically, he had to design the vast People’s Hall to contain mass demonstrations of over 150,000, which required such an immense scale that Hitler himself, when he appeared on its grand ceremonial balcony, would literally have disappeared “to an optical nothing,” zu einem optischen Nichts.[8] For Sebald, it is this sort of drastic shift in perspective, more than the buildings themselves, that encapsulates Hitler’s most secret desire. Paraphrasing Speer’s observations, Sebald writes, “Thus Hitler was so enthused by the pyramids, those petrified extensions of domination and the irreversibility of death, which obsesses the paranoiac emotionally because death—as the administrators of Kafka’s castle well knew—represents the most random but also the most seamless of all systems of order.”[9] The quest for perfect order becomes the desire for death only because the paranoiac cannot keep things in the proper perspective. This is a lesson already available in the teachings of Kant: To apprehend the sublimity of the Egyptian pyramids, he explains, one must regard them from the proper distance; viewed from too close up, their sheer scale and upwards sweep overwhelm the individual, but from too far away they lose their grandeur and appear as simple geometric shapes.[10] Perhaps this rule explains the sense of perspective that eludes both Canetti and Speer: where Canetti’s efforts to fathom the essence of Hitler’s power are overwhelmed by the sheer, unfathomable excessiveness of it all—the scale of the masses, the scale of delusion, the scale of brutality[11]—Speer’s memoirs view recently past events from a contrived distance in which events appear as diminutive as the architectural models he made for Berlin. Unlike those two, who spoke directly from experience, Sebald, writing from the next generation, was perhaps just far enough away to attain the proper lack of distance.

Or anyway, that’s how the scale model looked that Speer constructed for Hitler. The perfect white replica of the future imperial capital, Germania, that one sees in the pictures,[12] usually accompanied by the suggestive factoid that it was housed in an exhibition hall of Speer’s Akademie der Künste that could be conveniently reached from Hitler’s Chancellor’s Headquarters via the adjoining garden, allowing regular midday visits even in the midst of the war. Already in 1925, while still in Munich, Hitler had prepared his own sketches of the Triumph Arch and the domed People’s Hall, which he presented to Speer as a gift in 1935, and Speer returned the favor in 1939, when he surprised Hitler on his fiftieth birthday with a four-meter-high model of the Triumph Arch that left the Führer speechless.

Obsessed with seeing his dream city realized within his lifetime, Hitler insisted the 1950 deadline for completing the first stage of the plans to rebuild central Berlin (including the dome and arch) be met regardless of the war.[13] Indeed, Speer recounts, Hitler was at times too distracted with detailing his plans for the 1950 inauguration of the New Berlin to attend strategy sessions for the imminent invasion of Russia. In 1941, Hitler even delayed executing for six crucial weeks an order, personally urged by Speer, to transfer 30,000 skilled steel workers away from the Triumph Arch construction project to the Russian front to assist in repairing railways destroyed by the Russians as they retreated, railways crucial to resupplying badly overextended German troops facing the onset of the Siberian winter.[14] Increasingly beset by the bad news from the Russian front, Speer recalls, Hitler was able to be “lively, spontaneous, and relaxed” only during those regular visits to his model city; imagining himself as a traveler first arriving in the new southern train station of the imperial capital, he would stoop down and gaze through the triumph arch and down the grand boulevard to the dome, allowing himself to grow so overwhelmed by the miniature spectacle that he would weep with excitement and gratitude.[15]

In retrospect, Speer contends, he felt disquieted by his own designs—especially the shift in “my style” from a modernist rendition of early Doric simplicity to a gratuitously supersized, insistently monumental “Late Empire” style—post-Napoleonic bombast that Walter Benjamin once all too alluringly termed “the style of revolutionary terrorism.” For Speer, the style brought to mind the Satrapenarchitektur—the style of the ancient Persian despots, the Satraps—familiar to him primarily, he admits, through the garish film sets of ancient Babylon built in the Hollywood hills by Cecil B. DeMille. (One needn’t seek out an archive of silent films to view examples of such Satrapenarchitektur. The 2000 French documentary Uncle Saddam—filmed in the years just before the second Gulf War—offers a virtual tour of Saddam Hussein’s equally drastic and bombastic plans to rebuild Baghdad, guided by the ruler’s architect, one of his distant nephews; also the more recent documentary, Gunner Palace, which charts the daily lives of American troops quartered in one of Saddam’s once lavish but now bombed-out palaces.) It is in another example of Late Empire monumentalism, the colossal Antwerp train station, that Sebald first encounters Austerlitz, who immediately sets out to explain how Belgium in the era of King Leopold sought to assert its newly won global economic leadership status—the fruit of its Congolese colonies—by erecting this massive station. Its towering domed entryway was designed to transport the newly arriving traveler into a realm beyond profanity, into “a cathedral of world trade and world traffic,” its balconies adorned with the pantheon of the new gods of industry—Mining, Industry, Transportation, Trade, and Capital. And in the dominant position, as king of these gods, Time itself, in the form of a great clock, whose mechanical hands would control the movements of travelers by synchronizing the trains, and with them all traffic and commerce, across the entire continent, commanding the very interaction of space and time in a way that can only appear to the traveler, once the journey is complete, as something altogether illusory—“just as always, I recall Austerlitz remarking, our best plans find a way, in the course of their realization, to become their exact opposite.”[16]

The cornerstone of what was to be the world’s tallest triumph arch, sinking slowing into the sand—was it just a kind of inverted hourglass, a perverse historical clock set to measure the speed of civilization’s reconstruction against the motionless inevitability of gravity’s downward pull? Would such a gravitational sand clock be triumph’s exact opposite?

The Nazi ascendance to power as a reversal of history itself, a rebirth into an era of permanent triumph—this was the “triumph” of the 1934 film Triumph of the Will. The theme of “German rebirth” was entrusted to Leni Riefenstahl, whose visual architecture of narrow juxtapositions formed a virtual cinematic triumph arch—laughing children riding each other’s backs in mock chariot races, Nazi officials in shiny convertibles, geometrically arrayed masses of storm troopers stiffly goosestepping through the narrow, ornate streets of old Nuremburg. Even today, watching Riefenstahl’s propaganda tour de force remains a gripping ordeal; one can hardly imagine its effect on masses of ideologically overstimulated Germans packed into ornate cinema palaces for quasi-compulsory viewings, simultaneously terrorized and enthralled into joining the laughter, cheering the speakers, and marching Sieg-Heil-ing through this narrow cinematic rite de passage into the Nazi worldview.

Reportedly it was Hitler himself who insisted on the film’s title, with its clear reference to the Nietzschean “Will to Power.” It is less likely that Hitler was aware of a deeper allusion in the word triumph itself. The Latin form triumphus stems from an ancient Greek word, thriambos, an exclamatory term associated with Dionysian religion whose etymological ur-meaning remains unclear (at least according to the OED). Though commonly connected with the Roman military ceremony, the original connotation of the word triumph is in fact not victory but the arrival of Dionysus, the “dying and reborn” god whose perennial return was celebrated with revelry and ritual chanting of the word thriambe, thriambe.[18] Eventually, the Greek rite morphed into a ritual whereby leaders were invested with divine power; transmitted via the Etruscans to the Romans, it became a ritual whereby the victorious general and his troops were temporarily granted godlike power on their return from battle, in order to then be reintegrated into the civil order. Thus, triumph originally designates not the thrill of victory but its more ambivalent aftermath, the evocation of an enthused sense of divine possession that could only be brought to an end by expending itself in manic celebration. It is hardly a coincidence that this original sense of triumph as a sort of cyclical mass exuberance recurs in early attempts to describe the manic episodes associated with bipolar disorder in individuals: “[It] cannot be doubted that in cases of mania the ego and the ego-ideal have fused together,” Freud noted, “so that the person, in a mood of triumph and self-satisfaction, disturbed by no self-criticism, can enjoy the abolition of his inhibitions, his feelings of consideration for others, and his self-reproaches.”[19] So ambivalent was the prospect of this recurring triumphal mania that—some have speculated—the original Dionysian revelers were not allowed to enter the community through a normal gateway at all and instead a special entry was broken directly through the city’s walls: the first triumph arch as a rupture in the barrier separating civilization from chaos, meaningful history from mindless repetition.

Was Hitler’s triumph arch to be just such a gateway—between death and life, defeat and victory, traumatic past and triumphal future—that never fully opened but now waits, indestructible but slowly sinking, to be finally closed? Certainly, if there was ever an historical era of triumph, it still endures—at least to judge by the words of the American president who recently declared, on the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, the inevitability of “freedom’s triumph over all its age-old foes.”[20] Precisely to the extent that the word triumph has come to signify something like an absolute, final victory, not just the felicitous gaining of the upper hand over worthy competition but the righteous vanquishing of an unworthy foe, it also signifies something pre-ordained, inevitable—and thus, presumably, something one is justified in announcing even before the final victory is declared. Yet by this (admittedly mythical) logic, is the triumph gateway something that is opened even before the arch is finally built? Is this the message one gleans from a concrete block’s mute mockery?

Text by Eric Schwab. Photographs by Walead Beshty. The author dedicates this article to Eli Sagan. He would also like to thank Offer Egozy, Ann Toebbe, and Martin Blume for their thoughtful contributions. All translations from the German are the author’s, unless otherwise noted.

- Albert Speer, Erinnerungen, (Berlin: Propyläen, 1969), p. 169.

- Hans J. Reichhardt and Wolfgang Schäche, Von Berlin nach Germania. Über die Zerstörungen der “Reichshauptstadt” durch Albert Speers Neugestaltungsplanungen (Berlin: Transit, 1998), pp. 138–139.

- W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2001), pp. 31–32.

- W. G. Sebald, Luftkrieg und Literatur. Züricher Vorlesungen (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2000), p. 17; Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction, trans. Anthea Bell (New York: Random House, 2003), p. 67 [translation slightly modified—ES].

- Elias Canetti, “Hitler, nach Speer” (1971), in Das Gewissen der Worte (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 1981), p. 172.

- Ibid., p. 174.

- W. G. Sebald, Summa Scientiae. System und Systemkritik bei Elias Canetti, in Die Beschreibung des Ungluecks. Zur oesterreichischen Literatur von Stifter bis Handke (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 1994), p. 95.

- Speer, Erinnerungen, p. 168.

- Sebald, Summa Scientiae, p. 95.

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, Section 26.

- See the final sentence of Canetti’s essay (p. 199): “The shame over this situation, the insight into this disgrace, the essence of this false vision—everything comes together here into an indestructible impression.”

- Most recently in a scene from Oliver Hirschbiegel’s 2004 film Downfall [Der Untergang] in which one first glimpses Hilter (Bruno Ganz) bent down and peering gleefully through the Triumph Arch to see the view down the grand boulevard.

- Document reproduced in Speer, Erinnerungen, illustration before p. 193:

GENERAL ORDER from: Adolf Hitler, Headquarters, Berlin, June 25th 1940

In the shortest possible time, Berlin must undergo an architectural reshaping in order to assume that outward expression which will be commensurate with the greatness of our victory—as the capital city of a mighty new empire.

In my view, the realization of this henceforth most important building project of the Reich will be the most important contribution to ultimately securing our victory.

I expect its fulfillment by 1950.

The same holds true for the reshaping of the cities Munich, Linz, Hamburg, and the Party buildings in Nuremberg.

All posts in the service of the Reich, States and Cities as well as the Party shall yield every requested assistance in executing the projects of the General Building Inspector for the Imperial Capitol Berlin.

—AH

Speer, the General Building Inspector referred to in the note, adds the following caption: After returning from Paris, Hitler received me in the little den at his farmer’s cottage; he was sitting alone at the table: “Prepare an announcement in which I order a total resumption of the Berlin construction projects. ... Wasn’t Paris lovely? But Berlin must become even lovelier!” Hitler hand-inscribed the date, which marked the cease-fire with France—the date, as Speer remarks, of Hitler’s “greatest triumph” (p.188). - Ibid., p. 200.

- Ibid., p. 147.

- Sebald, Austerlitz, p. 46.

- Ferdinand Noack, Triumph und Triumphbogen (1928), quoted in Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap, 1999), p. 97.

- See H. S. Versnel, Triumphus. An Inquiry into the Origin, Development, and Meaning of the Roman Triumph (Leiden: Brill, 1970), especially pp. 37ff. and 300ff.

- Sigmund Freud, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, trans. James Strachey (New York: Norton, 1959), p. 82; originally published as Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse (1921).

- George W. Bush, “Securing Freedom’s Triumph,” The New York Times, 11 September 2002.

- Walter Benjamin, Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century (ca. 1925/26), in Reflections, trans. Edmund Jephcott (New York: Schocken, 1978), p. 148.

Walead Beshty is an artist and writer currently based in Los Angeles. His work has recently been on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, White Columns, The Museum of Contemporary Photography, and P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center. His writing has appeared in Aperture, Afterall, Artforum, ArtReview, Site, Trouble, and Texte zur Kunst. He currently teaches in the art departments of CalArts and UCLA, and is represented by Wallspace in New York and China Art Objects Galleries in Los Angeles.

Eric Schwab has taught and written extensively about Berlin’s history and culture. He was the author, with Walead Beshty, of “Willkommen in Irak!” (Cabinet no. 15). He currently lives in Chicago and studies law.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.