Absolute Power: An Interview with Sharon Beder

A history of global electricity markets

Jeffrey Kastner and Sharon Beder

Though scientists such as Michael Faraday and Werner Siemens had been working on methods for the large-scale generation of electric power throughout the mid-nineteenth century, it wasn’t until 1882 that Thomas Edison opened the world’s first central electricity generating operation at Pearl Street Station in Lower Manhattan. What started with one 125-horsepower generator powering some 800 light bulbs in the city’s Financial District became, over the following decades, one of the world’s most important and lucrative businesses. Central to the story of the electrical power industry in the twentieth century were the ongoing, often fierce debates over who should own and benefit from it. Political battles between advocates of private provision and supporters of public stewardship have been replayed again and again over the course of the last 125 years, a dispute that opens a window on the larger narratives of American and global socio-economic life—from the rise of the conglomerates to the 1929 Stock Market Crash and the resulting New Deal legislation of the 1930s; from neo-liberalism’s birth in the philosophical crucible of the Reagan and Thatcher revolutions of the 1980s to its policy dominance of increasingly powerful world monetary organizations at the end of the twentieth century; and up to the present day, as developing countries around the world increasingly find themselves reassessing the orthodoxies handed down by their Western benefactors. A professor at the University of Wollongong in Australia, Sharon Beder is the author of Power Play (The New Press, 2003), a history of the electrical power industry. She spoke with Jeffrey Kastner from her home in Australia.

Cabinet: You pick up your story at the end of the nineteenth century—what was going on in the electricity industry at that point?

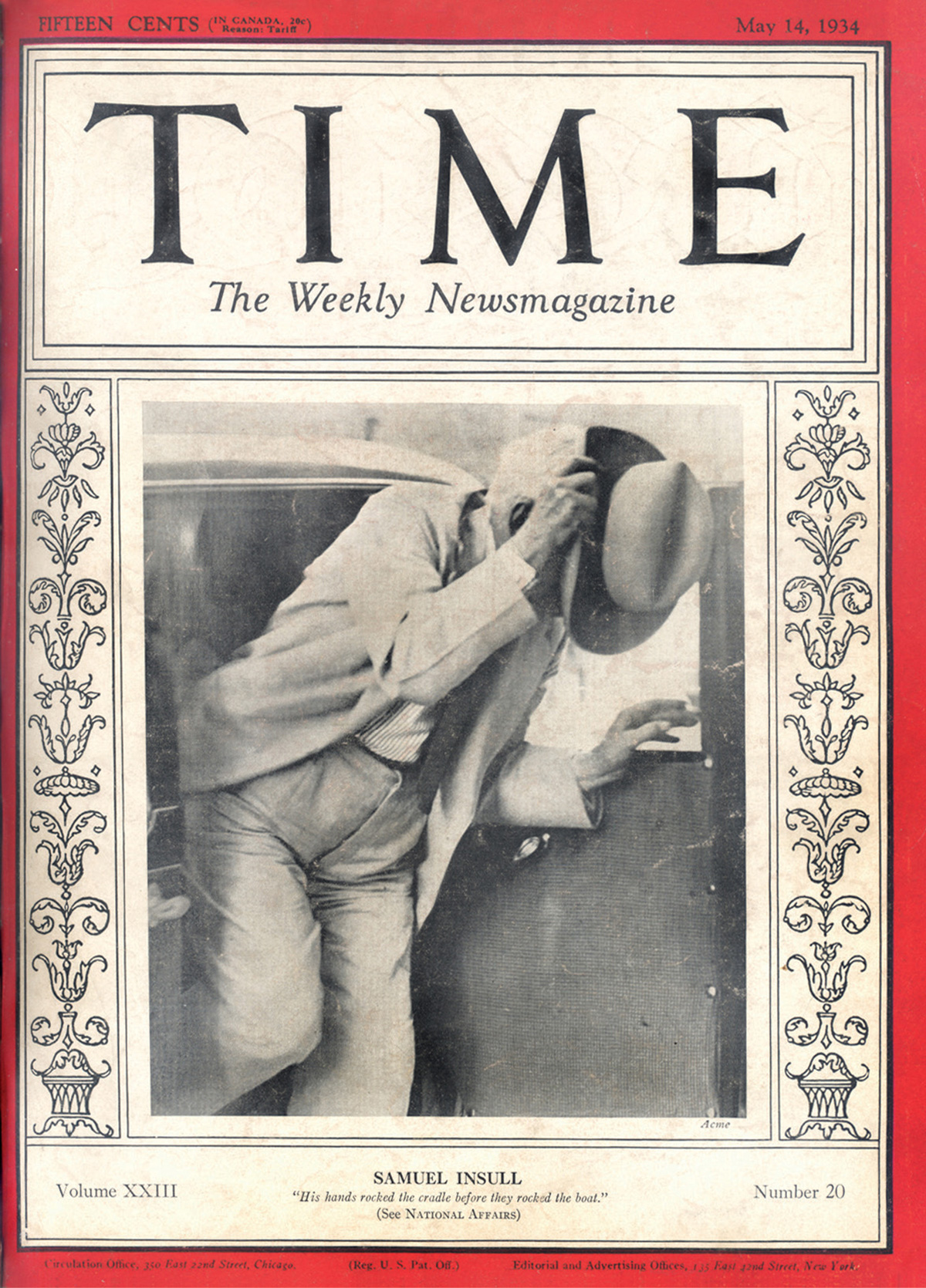

Sharon Beder: The electricity industry in the US at the end of the nineteenth century was owned by a mixture of municipal councils and private companies. Street lighting was electrified first and the companies or councils that were involved in that expanded into other areas. Large companies also generated their own electricity and sold what they didn’t need. There was quite fierce competition both between private companies and the municipalities, and between individual private companies. The private companies were particularly opposed to the municipal supply of electricity, not only because it deprived them of business opportunities but also because publicly owned electricity tended to be cheaper and more reliable. As a result, municipal provision was increasing at the expense of private provision. So the private companies and their allies lobbied against public ownership with the aid of bribes to individual councilors, bank boycotts on lending to councils, and General Electric boycotts on selling equipment to councils. A key person in all this was a fellow named Samuel Insull. He was the head of the National Electric Light Association (NELA), the trade association for private electricity companies, right from the end of the nineteenth century. He thought that the way to win the competition against public utilities, and also to consolidate power within the private sector, was to have state-regulated private monopolies. He used the argument about economies of scale to make the case for monopolies, which did have some justification—he said that in any one town there should be just one supplier of electricity because that was most efficient, rather than having duplication of infrastructure. And this monopoly would be regulated by the state.

Which gave it a veneer of public oversight.

It was supposed to satisfy the public because they would then think that although some of these monopolies (and Insull was hoping most of them) were owned privately, they would still be regulated by the government and so they would be acting in the public interest because of that regulation. This was a way of getting the public to accept private monopolies and avoiding damaging competition between private companies.

So it was essentially a way to consolidate power and do it in a way that would appear to satisfy the public interest. But was this in fact all basically a scam, a semantic game?

What Insull understood through his previous dealings with politicians was that any regulatory agency could be bought. They were already doing this at the local level, and they figured that if they had state regulation, instead of having to deal with lots of little councils and municipalities, they could just deal with the state regulators. And that’s of course what happened, because usually the state’s regulatory agency and its commissioners were, let’s say, open to persuasion. For example, Insull contributed $272,000 to the Senate campaign of the chair of the regulatory commission in Illinois in 1926. The regulators were also offered jobs with the utilities when their terms of office ended, not to mention the way the companies used their influence with the state governments to put particular appointees on the regulatory commissions in the first place.

Was there no legitimate economic rationale for the industry approach? You do concede that there were real economies of scale involved.

It makes some sense to have monopolies, but what happened in other countries that didn’t happen in the US is that while they recognized that electricity was most economically provided through a monopoly, they generally opted for public, not private, monopolies. What happened in the US, through the maneuvers coordinated by Insull, was that they managed to prevent the forms of nationalization, or public ownership, of the monopolies that developed in places like Australia, Britain, and Italy. They too started out with mixed ownership, but they soon realized that if monopolies were necessary, then they needed to be owned by the government.

So in the early twentieth century, private companies had found a way to preserve functional private monopolies that nevertheless had the cover of public supervision. And up to the collapse of the American stock market in 1929, the system was essentially dominated by private ownership. In the wake of that, however, these issues began to play out in the politics of the New Deal, with the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority and Rural Electrification Agency.

Until the Depression, these electricity companies consolidated and merged and became very powerful, especially the holding companies that came to control them. Through their structures and the way they charged rates, the conglomerations and holding companies padded out their expenses, exaggerated the value of their assets, and got people to invest in them without any real voting power. Most of that investment went to pay dividends to stockholders in the top holding company. That pyramid structure and inflated stock prices contributed to the collapse of the holding companies at the time of the crash. Some people even argue that it was the electricity companies crashing that started the whole ball rolling. Many were made bankrupt, but it didn’t mean they stopped operating. Instead, the banks took over and became a large part of running electricity companies at that time. Of course, banks have played a key role in electrical provision right from the beginning because it’s such a moneymaker and the projects tend to be very capital-intensive—to expand, you need big bank loans and the banks got involved on the boards of the electricity companies, so they had a lot at stake.

So was the move in the 1930s in the US toward more government involvement inspired by the excesses of these power-holding companies?

People were disillusioned and there was pressure for public ownership, and campaigns in various states for it. Electricity wasn’t being supplied in rural areas, for example, because the private electricity companies tended to focus on where the most money could be made, which was in areas of high population density. So there were real gaps in electricity provision and, with the New Deal, the government had signaled that it was ready to spend money on public infrastructure and it got into this whole area of electrifying rural areas that were being neglected by the private sector.

How did the private companies react to this reversal of fortune?

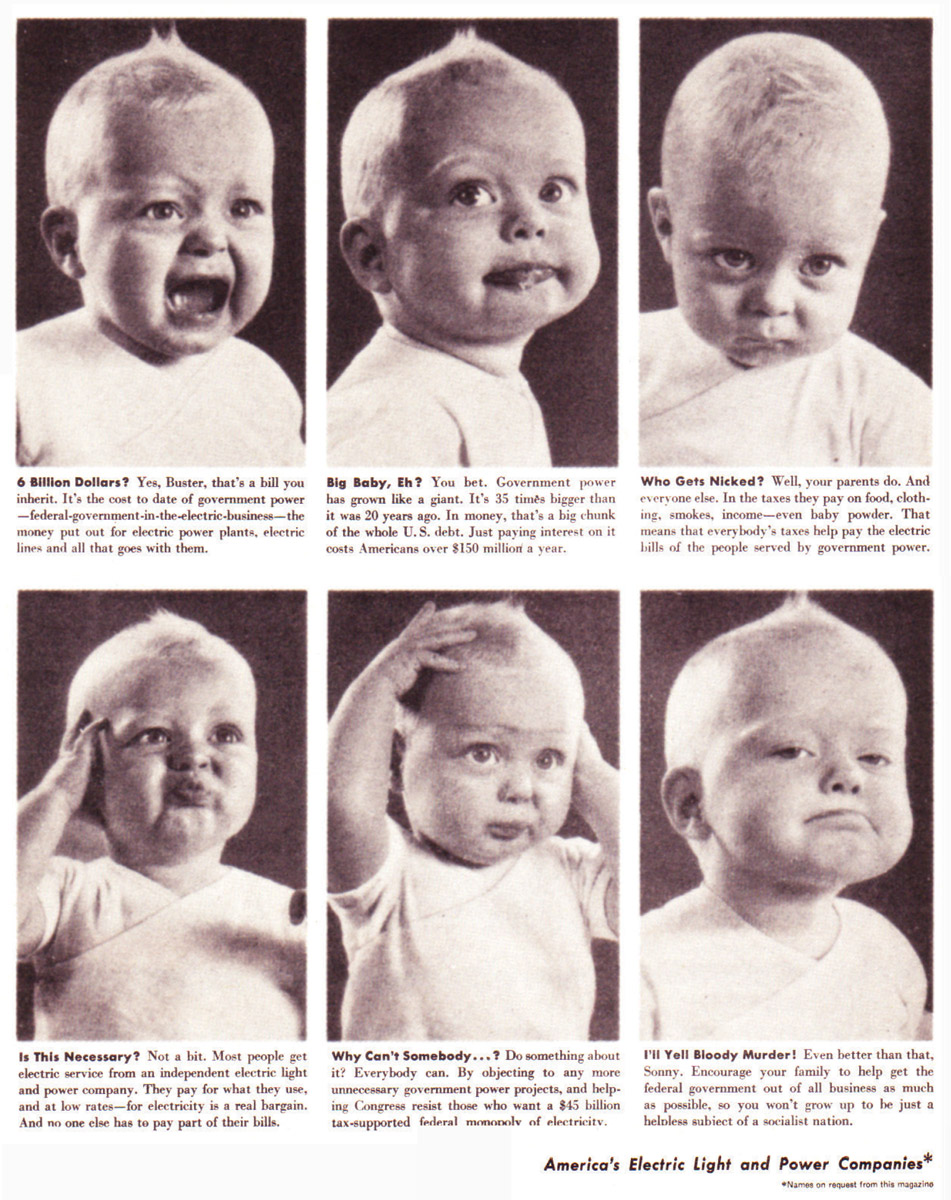

Well, the companies responded quite aggressively to head off campaigns for public ownership through massive propaganda both before and after World War II. And it wasn’t just in the media. It was in the school books, through the churches, in every avenue of life. For example, the private electricity companies tried to buy up the most influential newspapers around the country, funded private press services, and, in the case of the Edison Company, even built and operated a radio station, all to ensure pro-private utility media coverage. School materials were distributed, including booklets on “Our Public Utilities” and textbooks were edited and removed from reading lists. University professors and research institutes were funded to write textbooks that favored private utilities. They were quite sneaky about it—organizing women’s tea parties where they would plant people to just bring up in conversation that public ownership was a bad thing, that it was the thin edge of Communism, and so on. So people were getting this message from all sorts of places, but often in such a way that it was not obvious that it was coming from the utilities themselves. And it wasn’t just negative against public ownership but, of course, also positive for private ownership. Private ownership was portrayed as essentially public ownership because the public owned shares in electricity companies, particularly through their pensions, etc.

And it seems to have worked—notwithstanding the politics of the New Deal, you note in your book that by 1965, seventy-six percent of the power in the US was privately provided. So despite the swings back and forth between political preference for private or public ownership, the private providers were winning.

Private companies took over more than a hundred publicly owned systems after World War II and in the 1960s were still charging more in rates than the remaining public ones. But no one seemed to notice, because over time rates did not rise. The fight had gone out of the campaign for public ownership. It was only in the late 1970s when electricity companies began to invest in nuclear power that rates began to soar and environmentalists began to target electricity companies.

As deregulation becomes a bigger issue in the early 1980s, this all gets rolled into the larger political debates surrounding people like Reagan and Thatcher and the rise of neo-liberalism in general, and specifically its rhetoric about free versus planned markets.

In general terms, the private companies had managed to get private monopolies by advocating state regulation, and now with deregulation they wanted to dismantle those regulations as well. If they wanted to raise rates, they still had to get approval from the state regulators, and so they still had to go through the process of lobbying and making sure the right people were on the commission. And there was also regulation about holding companies that was the result of the 1929 crash—a piece of New Deal legislation called the Public Utility Holding Company Act that was designed to put a brake on the conglomeration and consolidation of electric companies. By the beginning of the 1980s, the momentum was actually for getting rid of monopolies, so that there would be competition. But the push for this was from the big electricity-using corporations and industries, which thought they could get cheaper electricity if new companies were allowed to come in and provide it for them. The existing regulated monopolies had these big debts from building nuclear power plants and their prices reflected this. What the big electricity-using corporations wanted to do was to avoid paying higher rates to cover the costs of prior nuclear investment. At the same time, there were new processes available for producing electricity—in particular, gas-fired electricity plants—and you didn’t need such a big investment for this technology, so the big industrial electricity consumers liked the idea of new entrants to the market being able to compete rate-wise with these large debt-laden utilities. And there were also companies like Enron, to name one particularly infamous example, which saw a lucrative role for themselves in all this as middlemen, as traders.

Speaking of Enron, you write in your book about the 1992 Energy Policy Act, which essentially opens up this sort of trading. What exactly does it mean to trade electricity?

In the old system, the utility monopolies that generated the electricity also owned the power lines that transmitted and distributed the electricity, and they controlled sales of electricity to consumers. Any new company coming into the market to generate electricity had no means to distribute it unless they could use the existing transmission lines or build their own, which would have made the whole enterprise uneconomic. The Energy Policy Act ensured that power lines could be used by whoever wanted to enter the market. Because of the Act, the existing utility companies had to allow competing companies to use their power lines for reasonable fees. This enabled competition to occur at both the generation end of electricity supply and the retail sales end. The Act also forced states to open their electricity sectors to competition. In various states, the utility companies were required to sell off some of their generating plants to encourage competition. It also enabled independent companies to trade electricity, that is, to buy electricity from generators in a wholesale market and sell it to users. This opened the doors for companies like Enron that were able to buy and sell electricity that they themselves did not generate. At the same time, electricity was being privatized in other parts of the world and that privatization was offering opportunities for American companies like Enron to go and buy up electricity companies around the world. So one aspect of the background to American deregulation was that companies that were investing overseas wanted the same opportunities back home, and so they also supported deregulation in the US.

But your book also highlights the role of global monetary organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which during this time essentially became a kind of mechanism to promote deregulation and economic neo-liberalism. And in fact it became a tenet of these organizations to promote this model for utility operation around the world.

That’s right. They adopted the neo-liberal ideology, and with it the idea that in developing countries the provision of electricity should be done privately rather than by the government. The rhetoric was that pre-existing facilities needed to be privatized in order to inject extra capital needed to fund the expansion of infrastructure in developing countries. But, in fact, the reason the governments weren’t able to do the expansion themselves was that the World Bank and the IMF had stopped lending money for the government provision of infrastructure, and decided to lend money to the private sector instead.

So these supposedly independent monetary organizations end up being the main way the message of economic neo-liberalism from the US gets spread around the world. How does this happen?

Well, political domination of these organizations by American interests is a large part of it. The voting power in these organizations is dominated by the US—the US has the right of veto in the World Bank and an effective veto in the IMF and appoints the Bank’s president. So it has a lot to say about the development of policy. But also, more than eighty percent of the World Bank’s economists, who are far more influential than the social scientists employed by the Bank, were trained in either Britain or North America, often at American universities that were promoting the neo-liberal economic philosophy, like the University of Chicago. And the representatives of other countries on the World Bank and IMF not surprisingly tend to come from economics-oriented ministries rather than from the health or environment ministries. So to the extent that the neo-liberal message was spreading through the economic professions, the World Bank and IMF were being converted as well.

Your book includes several national case studies. One particularly interesting one focused on Brazil, which relied on hydroelectric power for ninety percent of its electricity production as late as the 1980s.

Brazil was a country that had a very effective public electric system, one that was reliable and that provided affordable electricity to most of its population. It was a system that was working well to start with. But under pressure from the World Bank and IMF to privatize, they began selling off various parts of their system, with dramatic results. First, electricity prices rose drastically. Secondly, when it came to needing more electricity—when it became necessary to expand generation capacity—these new private companies weren’t willing to invest without all sort of guarantees on returns. And the government, which could have in other circumstances funded the expansion and had done so over decades before, was no longer able to under World Bank and IMF rules. So Brazil went from a situation of having plenty of cheap electricity to having to ration it because there was such a shortage. The big winners of the privatizations have been the electricity companies, the intermediaries, and the traders, as well as the banks and the consultants—there’s a whole industry that benefits from privatization. And Brazil is far from an isolated incident. You could also look at the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, Papua New Guinea, India...

So have these recent failures of privatization, or something like the Enron collapse, had an impact on public attitudes?

Not so much the collapse of Enron, because I’m not sure to what extent the public associates that directly with deregulation and privatization. But I think that the message has gotten out in more recent times that the crises that happened around the world, starting with California—where electricity prices soared and the companies tried to explain it in terms of increased demand and environmentalists stopping expansion of new facilities—were crises generated by private greed and by companies, in the California case by Enron and others, manipulating prices to make more money.

Can you quickly summarize what happened in the 2000–2001 California energy crisis?

In the new deregulated system, generating companies offered specific amounts of electricity for each hour of the next day for specified amounts of money. The system operator would work out how much was needed for each hour and accept the cheapest offers to fill that requirement. All electricity used would be paid for at the most expensive price out of all the offers that had been accepted for that hour. The thing was, the generating companies knew at what times most of the electricity offered would be required and could manipulate the price by holding back some electricity for that time period and offering the rest at hugely inflated prices. The companies that supplied the electricity to the customers—the utilities that had been required to sell off much of their generation capacity—had to buy the electricity at these inflated prices. But in places where the retail price had been frozen, they couldn’t pass the higher costs on to the customers. Basically the whole situation was created not because the demand was any higher than in previous times, but because of price manipulation through withholding and other mechanisms.

Weren’t there also power shortages and blackouts related to this manipulation?

There are some theories that actually as the big utilities that sold the electricity to consumers were feeling the pinch, they forced the government into bailing them out by not paying their bills and deliberately creating a situation of blackouts that the public wasn’t going to stand for so that the government would have to bail them out. This was even though their parent companies had made money hand over fist from the same system. So the situation was not just artificially high prices through artificial shortages, but artificial blackouts that were manufactured for a political purpose.

What are current attitudes to privatization outside the US?

Well, throughout South America and Asia where electricity or other services have been privatized, prices have soared and these are countries where many people cannot afford high prices for electricity. But the effects of privatizing have been felt very heavily in Latin America. And you can see what’s happening now with the turn against neo-liberalism and the Washington consensus because these people are experiencing the effects directly.

This is happening with Chavez in Venezuela, with Morales in Bolivia—a general rejection of American-style economic liberalism. So what is the strategy for them? To bar foreign investment and the kind of trading that operates globally now in order to take their electrical systems back into a nationalized framework?

Because privatization of electricity has not been completed in many countries, they have an opportunity to stop it. And in some countries, the campaign to stop privatization is very fierce; people have actually gotten killed in places like Papua New Guinea and South Korea, where following the deaths they have for the time being stopped the privatization process. But Korea is also one of those developed countries that has more of a choice about these things because they are less reliant on IMF or World Bank funding. But my impressions from a recent visit were that there’s still enormous pressure on Korea, not so much lending pressure but pressure from international organizations and other governments for them to privatize. This pressure comes from international financial markets; organizations like the World Trade Organization and the International Energy Agency; transnational and national corporations which are large political donors; and from neo-liberal economists and think tanks. At some of the meetings I went to when I was there, organizations such as the International Energy Agency put forward the argument that unless they privatize, electricity won’t be efficient and they won’t be able to provide future supply, etc. So the propaganda argument is still that privatization is the only way they’re going to be able to provide electricity competitively and efficiently in the future. But what’s being lost is the fact that efficiency isn’t the only goal of electricity provision. There’s no point in having an efficient electricity supply where the benefits of that efficiency are all going to private companies—you’ve got to have a cheap, reliable, accessible electricity system for the people, and there’s not really much evidence that the private companies deliver that.

Sharon Beder, Professor at the School of Social Sciences, Media, and Communication at the University of Wollongong, is author of several books including Global Spin: The Corporate Assault on Environmentalism (Green Books, 1997), Selling the Work Ethic: From Puritan Pulpit to Corporate PR (Zed Books, 2000), Power Play: The Fight for Control of the World’s Electricity (The New Press, 2003), and Suiting Themselves: How Corporations Drive the Global Agenda (Earthscan, forthcoming).

Jeffrey Kastner is senior editor of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.