Object Lesson / Abject Object

Out and down in Paris

Celeste Olalquiaga

“Object Lesson,” a column by Celeste Olalquiaga, reads culture against the grain to identify the striking illustrations of a historical process of principle.

Animals approach the elimination problem differently. Cats, it is said, cover their stools so as not to leave any traces for potential enemies. Dogs evidently don’t share this refined ancestral instinct. Yet not so long ago in evolutionary terms, man’s best friend would eat its prey’s droppings, thereby camouflaging its own smell so as to surreptitiously approach an unsuspecting victim. Coprophagia isn’t a canine exclusive, either: rabbits gobble their turds to make the most of their nutrients, while koalas and elephants feed their feces to their young to transmit digestive bacteria. Animals use their ordure for marking territory and gathering information (who, when, and how), and humans appropriate it for construction, fertilization, and combustion—as cow dung proves so well.

While animal waste is a prime commodity in the ecosystem, human excrement is considered repugnant and worthless, except for purposes of medical analysis. Its removal is a massive undertaking compared by Dominique Laporte in Histoire de la merde (1978) to the socializing role of language: juxtaposing a selection of French literary and official texts from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, Delaporte argues that the transit from Latin to French as the official state language was not only symbolically intertwined with, but also as gradual and painful as, the process of dissuading citizens from throwing their excrement out the window. If Rome boasted of its cloaca maxima as the embodiment of civilization two millennia ago, Paris has finally been able, in the last few hundred years, to get its shit (or almost all of it) together.

Contemporary French cleanliness, while certainly less obsessive than that of New Worlders, is nevertheless unfairly berated: Paris is not only one of few cities in the world to offer street toilets (coin-operated service soon to be available for free), but has also seen the invention of two supremely effective modern cleansing devices: bidets and toilet paper. Although not as culturally catchy as their disposable counterpart, bidets (those oblong basins with built-in douches for personal hygiene) go back at least 250 years, when such a meuble de toilette was recorded as part of Madame de Pompadour’s 1751 expenses. The term bidet—which derives from the ancient French verb bider, to trot—typically designated a small saddle horse (whereby the association of shape and posture with the fixture), with related usages including “donkey” (Rabelais, 1534), “revolver” (1550) and bidet de compagnie, a small horse employed to carry the infantry’s tents in the days when war was still a body-to-body matter. Despite their popularity in those American epitomes of domestic bliss, the modern bathrooms of the 1950s, the American Medical Association in subsequent decades warned against bidets as hazardous, since bacteria could accumulate when they were not properly cleaned. Needless to say, this prohibition came much to the chagrin of a female population whose intimate parts bidets happily service in more ways than one—jealousy probably being at the core of this radical and unfortunate ban.

Quite different was the fate of that lasting invention, toilet paper. Evolving from the fourteenth-century toilette or tellete—a piece of cloth used for wrapping merchandise that often included objects of personal care (from toile, cloth, and tisser, weaving)—toilette was gradually applied to the elements and very act of washing and grooming, producing such well-known items as savon de toilette, eau de toilette and in 1902, papier toilette. In 1945, probably as a contraction of the term cabinet de toilette, toilette became a euphemistic name for that most denigrated of spaces, les toilettes, the WC, john, can, rest room, comfort station, girl’s—or boy’s—room, etc.

More scatological than eschatological (eschatology is a fascination with the end of the world; scatology with the end-product of intestinal activity), and always proud of exhibiting their heritage, the French must be the only people to have built a museum to their own merde. Comfortably seated at the edge of the Pont d’Alma (where Lady Di tragically met her own end), the Musée des Égouts de Paris is a monument to a culture so invested in food and drink that it fastidiously studies each and every step in their processing. Discussion of the production, acquisition, preparation, and presentation of food often takes up its whole period of consumption in banquets that can last several hours, depending on the mood of the diners—rather than on contingencies such as time and money, neither of which will ever prevent a good French meal from lasting as long as there is a steady supply of cigarettes, wine, and juicy items to criticize.

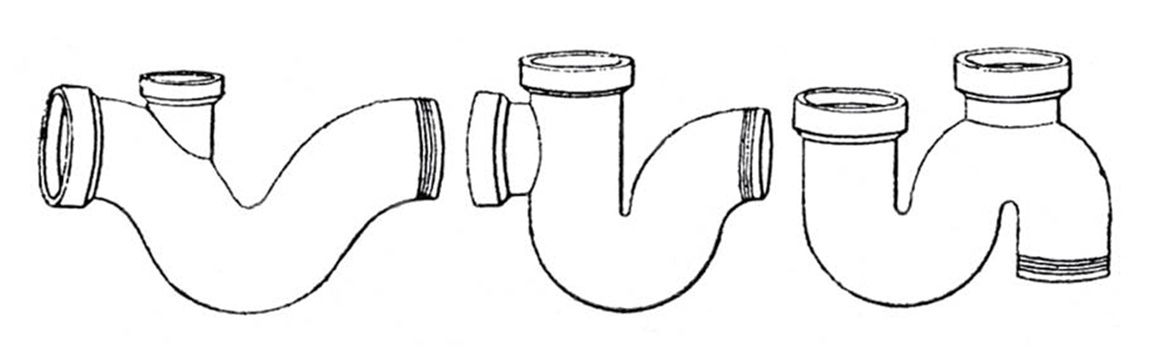

Given this penchant for ingestion, it should not be surprising that the “outcome” be considered if not equally, then at least relatively, worthy of interest. Conceived by the man who overhauled the Parisian sewage system, Eugène Belgrand (1810–1878), the Musée des Égouts was inaugurated in 1908 as the Musée sanitaire, later known as the Musée d’hygiène générale, which eventually changed river sides and adopted its current name. The institution pays tribute to urban burdens. Scarcely 1,000 meters long, yet probably the soberest (not a trace of golden leaf or other baroquisms here) and most odoriferous of all French museums, this marvel of the plumber’s art provides a unique and absorbing history of metropolitan development according to fecal disposal needs. Installed within the sewage system itself, the museum allows due admiration of sorting, filtering, and distributing mechanisms, as visitors breathe in the triumphs of municipal engineering on its bottom line.

Now about 150 years old, the Parisian sewers or égouts (from e-gout, to distill drop by drop) are the crowning achievement of a system primitively instated more than seventeen centuries before. The first grand égout, running down what is now the Boulevard Saint-Michel, was built in the Gallo-Roman city of Lutetia, before there was even a rive droite, and was destroyed in the third century by Germanic barbarians—who not only totally lacked in toilet training, but flung their sheitze at others. Two drainage systems were developed in the “Dark Ages” (perhaps so-called because of the “used” or “black” waters—as they are known in French and Spanish, respectively—that strutted their stuff down unpaved streets). One sewer paralleled the Montaigne St. Geneviève on the right bank, and the other was routed through the Arsenal basin (formerly a tributary of the Seine) on the left. Both evacuated directly into the Seine, which was, of course, also the main source of drinking water.

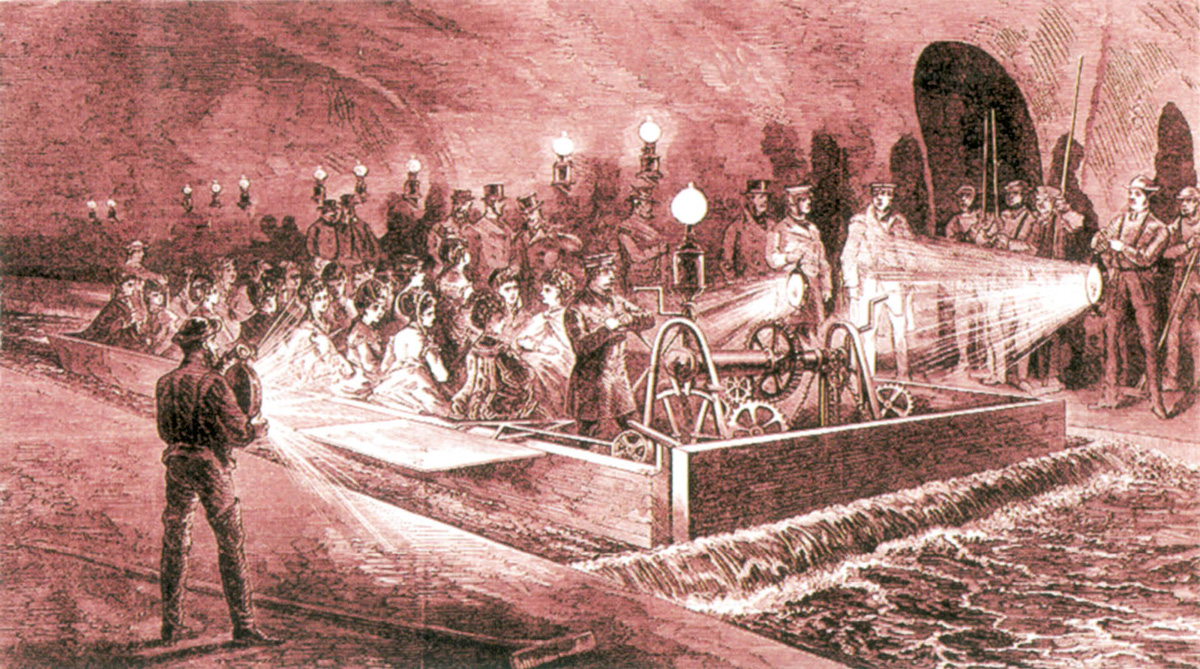

Until the nineteenth century, however, the only health hazard fully recognized was the reeking open sewer. Although the conduits began to be covered as early as the fourteenth century, the majority of the system would not be fully subterranean until the early 1800s. When the public plumbing was finally buried, it created a twenty-five-kilometer-long underground purgatory pungently evoked by Victor Hugo in Les Misérables (1862), in the chapter aptly entitled “L’intestin de Léviathan”:

Winding, fissured, unpaved, cracked, full of quagmires, broken by strange elbows, ascending and descending without rule, fetid, savage, ferocious, submerged in darkness, with scars on its pavements and gashes on its walls, gruesome, such was, viewed retrospectively, the old sewer of Paris. Ramifications in all directions, crossings of trenches, branches, goose-tracks, stars, as in mines, caecums and cul-de-sacs, arches covered with saltpetre, infected pits, scabby exudations on the walls, drops falling from the roof, darkness; nothing equalled the horror of this old excremental crypt; the digestive apparatus of Babylon, a den, a trench, a gulf pierced with streets, a titanic mole-hill, in which the mind fancies that it sees, crawling in the shadows, amid the filth which has once been splendor, that enormous blind mole, the past.

It wasn’t until a cholera epidemic exploded during the 1830s that the city’s septic situation was seriously reconsidered, leading to its massive overhaul and expansion in the second half of the nineteenth century. The renovation proceeded under Napoleon III, by order of the same Baron Haussmann who transformed Paris from a medieval maze into a modern grid, and was duly executed by the aforementioned engineer, Belgrand. By 1878, the sewer canals had grown to 600 kilometers, that is, 300 times their former length. Nowadays, they extend 2,100 kilometers (roughly the distance between Paris and St. Petersburg) in a complex network that also comprises running water (drinking and non-drinking), telephone lines, and part of the heating system. Eighteen thousand bouches d’égouts (sewer “mouths”) and 26,000 regards (“viewing-points,” used to access and inspect the system on the spot) attest to the anthropomorphic extension of the city’s bowels to mouths and eyes, in truly Rabelaisian fashion.

The same success story cannot be told regarding the excrement of homo erectus’s alter ego, the ubiquitous domesticated mutt, who is invariably present at the French table—as a voyeur, not a delicacy—although no respectable garçon would consider enforcing the dress code in this case. (Only after sharing a New Year’s dinner with one such creature at table did I feel fully accepted into French society. My gluttony later made me sick as a dog, but that was a small price to pay for the welcome.) Alas, many Parisians don’t think twice about allowing their canine counterparts to soil streets and sidewalks. Tourists may put up with tiny, unventilated restaurant facilities, whose operating instructions are cryptic at best, but dogshit succeeds where such cabinets d’eau fail: after slipping on one of the inevitable mounds—650 accidents are reported per year—the visitor finally loses patience with French public hygiene.

To be fair, Parisians have put up a struggle to eradicate this civic phenomenon. In-your-face ad campaigns on TV and in the cinema, and, particularly, onerous fines (183 euros per dump) are gradually achieving what the motocrottes (“shit-cycles” or ride-on pooper-scoopers) valiantly attempted between 1985 and 2004. Painted the standard sanitation-department bright green, these truly French contraptions—consisting of a motorbike, a container box, and a hose—were supposed to rid the city of its most unpleasant décor, literally vacuuming turds off the ground. Operated by sanitation workers, for whom regular garbage pickup must have appeared far more appealing, the 140-strong army of motocrottes was scarcely a threat to the sixteen tons of crap deposited daily by 200,000 pooches. After a good part of the fleet mysteriously burned in 2002, the city decided to abandon this strategy, to the relief of sanitation workers, street walkers, and pesky mongrels alike.

“The enormous blind mole, the past” can thus be appreciated in many guises, and the original abject object, shit, is one of them, as the study of coprolites, or fossilized dumps, strives to show. As for those too prudish or anal to admit that defecation is a part of life, the Indian fable of the man who sought redemption might come in handy: counseled by a wise hermit to find something more vile than himself, the man noticed his own “number two.” He was on the verge of gathering it when the caca begged him not to, claiming that it was once a delicious pastry and had been reduced to this foul state after coming in contact with the man only once. What worse fate could possibly await, were the man to touch it again? Enlightened by this encounter, the seeker became the most humble of men.

Celeste Olalquiaga is the author of Megalopolis: Contemporary Cultural Sensibilities (University of Minnesota Press, 1992) and The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury of the Kitsch Experience (Pantheon, 1998). She is currently writing a book on petrification. For more information and to contact Olalquiaga, visit “Celeste’s World” at www.celesteolalquiaga.com

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.