Fallen Fruit

Help yourself

Matias Viegener

On the corner of Finley and Dearing Streets in Athens, Georgia, grows a white oak tree that belongs to no one but itself. William H. Jackson’s love for this tree was so great that in 1820 he deeded it to itself, and it grows on a protected corner island to this day. To be precise, this is not the same tree. The original died at the approximate age of 400 in 1942, at which time the horticulture students at the local university planted an acorn from the original tree on the same plot of land. This “son,” the legal heir of the original tree, was featured in the original Ripley’s Believe It or Not series and has become one of the oddities on the tourist map. Its popularity may lie in the set of questions it provokes about humans’ relationship to the natural world: Can something we consider property own itself? What is the purpose of public space and who controls its use? Does nature serve us or do we serve it?

A corollary of these questions is another vexing area of property law: What happens when your neighbor’s tree grows over your land? Common law holds that you cannot destroy the tree, but you can prune or control any part that encroaches upon your airspace. Legal precedents are even more complicated when it comes to the ownership of the tree’s fruit. One interpretation holds that the tree’s owner also owns all the fruit, though he may have no legal access to harvest portions hanging outside his land, while another holds that the fruit, like the branches and leaves, may be disposed of as the lucky or unlucky neighbor sees fit. Many a homeowner has known this dilemma as he gazes upon a neighbor’s bounteous crop of apples or pears overhanging his fence.

What if the tree hangs over public space, a sidewalk, street, or alley? The status of this “public fruit” is even more unclear. Los Angeles is a good case in point. In a city of moderate density spread over a large area peppered with lawns, shrubs, trees, and even survivors of long-gone fruit orchards, public fruit is to be found on almost every block. Bananas, peaches, avocados, lemons, oranges, limes, kumquats, loquats, apples, plums, passion fruits, walnuts, pomegranates, guavas, and more grow year round in every neighborhood in the city. Urban public fruit, whether deliberate or accidental, is more efficient to grow than farmed fruit because it eliminates the cost of transport. Since it is not a mono-crop, as in an orchard of a single variety of apple, there are fewer pests and less chemicals required to treat them. A further irony is that most public fruit in Los Angeles is organic, blessed by neglect.

The question of food, property, and social responsibility is not a modern one. The Old Testament contains several injunctions to farmers and growers not to “reap all the way to the edges of your field, or gather the gleanings of your harvest ... or gather the fallen fruit of your vineyard; you shall leave them for the poor and the stranger.” (Leviticus 19:9–10) Today’s gleaners collect leftover crops from farmers’ fields after they have been mechanically harvested or from fields where it is not economically profitable to harvest. Gleaning was a legal risk until the 1996 passage of the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act, which promotes food recovery by limiting the liability of donors to instances of gross negligence or intentional misconduct. National food salvage programs work within the legal definitions of this act to regularly deliver surplus food from restaurants and shops to emergency food centers.

Gleaners also refers to those who live outside the conventional world, nomadic and without property, living without working and surviving on only the cast-off food they find. The Brahmin of India are likewise ascetics, but also rigorous vegetarians whose beliefs come through Hinduism’s equation of meat-eating with violence and with the karmic belief that such violence would be returned; certain sects of Brahmins are renowned for not harvesting and only eating fallen fruit. Today’s “fregans,” coined from free and vegan, are similar to gleaners, though they embrace more anarchistic notions of rejecting capitalism, labor, property, and the obligation to work and be productive. Their lifestyles are an active critique of the economics and values of modern life.

Our project, Fallen Fruit, began in response to a call for submissions in the summer of 2004 from the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest for work addressing urgent social and political questions, not in the form of critique or negation, but by proposing generative solutions. The problems of urban life seem obvious enough: disengagement, alienation from neighbors, and ignorance of the often grave needs of others, such as the homeless. Our approach was to address these problems through the coupling of waste and need by coining the term “public fruit,” and surveying our neighborhood to inventory this underlooked resource. Los Angeles is a particularly fertile city with an “artificial” ecology of great variety, as well as a fading past of agrarian values that mirror all American cities and especially their suburbs, with a fruit tree in every yard. Fresh fruit holds a poignant place in the mythology of California; early postcards often depict houses with swimming pools and orange trees against a backdrop of snow-covered mountains.

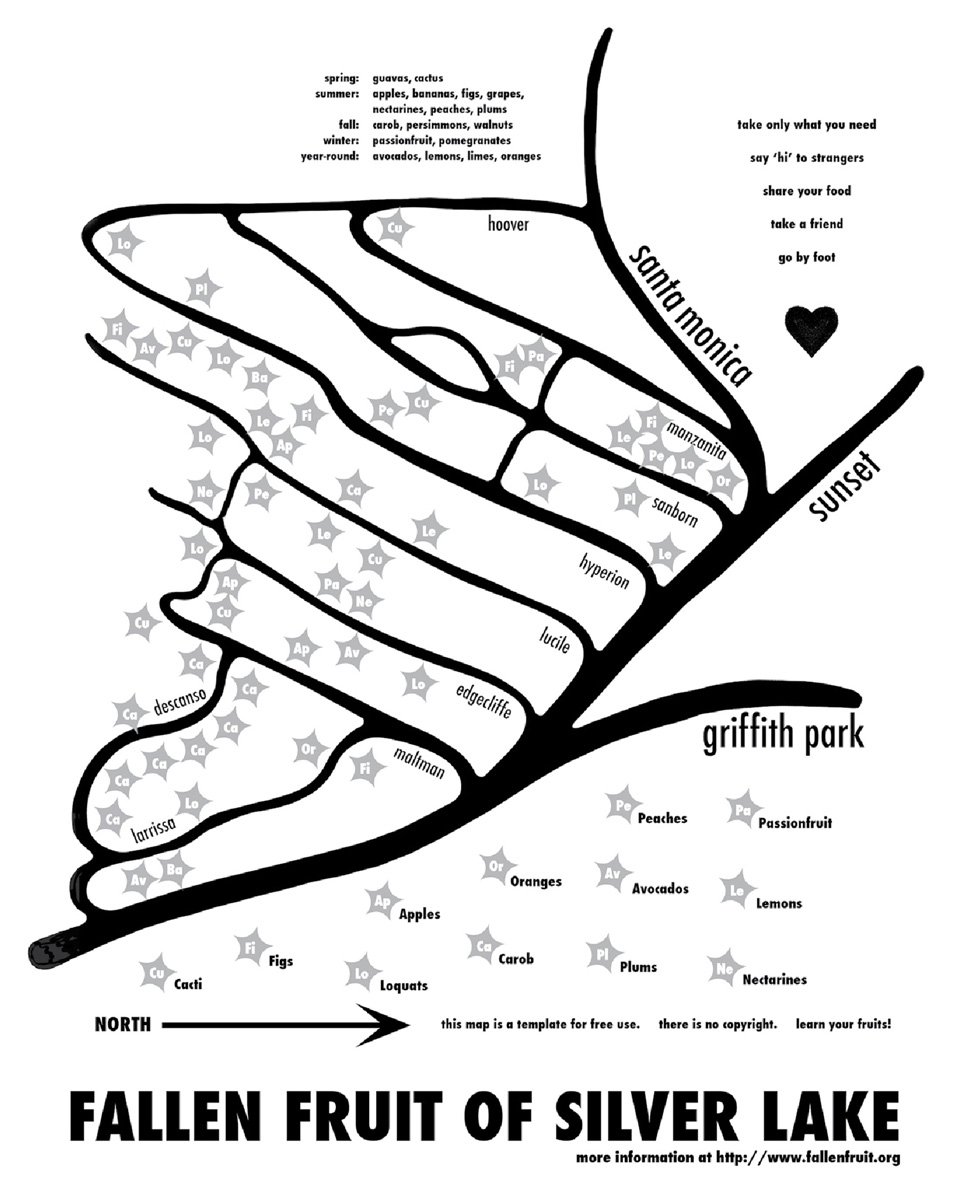

Fallen Fruit’s first project was to produce a map of all the public fruit within a five-or-so block radius of the homes of its three members (David Burns, Austin Young, and myself). The desire to map one’s neighborhood fruit has its seed in the wish to be in a fantastical California resembling the Garden of Eden. But in a city as auto-centric as Los Angeles, the simple mandate to either map or follow a map also obliges you to take to your feet and see the neighborhood from a very different angle, akin perhaps to learning about the strata of pipelines, tunnels, and subterranean wiring under all cities. Additionally, a fruit map suggests that the separation of city and farm is not real or absolute, and that all neighborhoods possess far more secrets than we know. The map of the Silver Lake neighborhood has spurred others to map their own neighborhoods, and the goal is to keep mapping, building a kind of unending, Borgesian fruit map that covers the world.

As with many activist-oriented projects whose purpose is to spur change, it soon became apparent that mapping or describing the world one would like to see is no substitute for actually making it happen. Fallen Fruit began to generate “propaganda” material urging property owners to plant trees on their perimeters and to generate a culture of public sharing. We organized a series of nocturnal fruit tours, both following the maps and looking for more public fruit. All of the residents we met while surveying and leading the fruit walks were not only curious about the crowd admiring their fruit, but invariably invited them to pick some, indicating that for a variety of reasons they never ate any or that they had far more than they needed. In a city with such great contrasts of wealth and poverty, the quantity of already existing public fruit is remarkable. This would be even greater but for the fact that many residents are reluctant to plant fruit trees because of the litter, or fallen fruit, that has to be disposed of; and it also needs to be pointed out that pedestrians are often reluctant to pick food within their grasp because they perceive it to be private property.

Fallen Fruit has proposed two public fruit parks, which would include only fruit or nut-yielding plants whose bounty is to be shared communally. They include demonstration areas, fruit-sharing depositories (so people can trade their excess fruit for other people’s), and informative plaques with thoughts about public fruit. One park was originally proposed for Griffith Park, the largest urban park in America. Most fruit-producing trees are not native to California, which means our park contravenes Griffith Park’s current policy only to plant natives; the park authorities have agreed, however, to consider siting the project in marginal land, probably by the LA River, that can be reclaimed. This park would be planted with the drought-tolerant varieties catalogued around the city’s neighborhoods: figs, loquats, walnuts, carob, avocados, and pomegranates.

The second park that Fallen Fruit has proposed is called the Endless Orchard, to be located in the park between the Music Center and City Hall in downtown Los Angeles, currently a hodgepodge of outdated and underused “green space” slated for renovation. The Endless Orchard is a ten-by-ten grid of fruit trees spaced twenty feet apart, the size of two city lots, enclosed on three sides by perfectly mirrored walls and open on the fourth side facing City Hall. The visitor to the orchard will experience the boundless vista of fruit trees that once characterized much of California, whose agrarian bounty was the state’s first engine of economic growth. The mirrors on three sides reference the state’s current economic investment in the business of creating illusions. The trees in the Endless Orchard will be 5-in-1 grafted fruit trees, with plums, peaches, apricots, nectarines and pluots, for example, all ripening at different times. Visitors are asked to take no more than they can hold in their hands—to sample, not hoard.

Fallen Fruit also engages in guerilla fruit plantings in which unwanted private fruit trees are “liberated” and replanted on public land. The volunteers are found through craigslist.org, where homeowners list their unwanted goods under “Free Stuff.” The fruit plantings generally take place in the evening with members of Fallen Fruit wearing their work clothes—brown worker’s outfits that resemble UPS uniforms.

There is a growing community garden movement in America, which has a kinship to the great popularity of farmers’ markets, and to the artisanal, organic, and slow food movements. All are responses not only to urbanization and to a perceived ecological crisis, but also to a globalized model of food production in which every step has been industrialized and monetized. Chez Panisse chef, Alice Waters, in Berkeley has founded a community school program called the Edible Schoolyard, which provides urban middle school students with a one-acre organic garden and classes in nutrition and cooking; the goal is to foster environmental stewardship and to revolutionize the school lunch program. Earthworks, a community organization in Boston, has had an Urban Orchards project since 1990. Funded by a grant from the US Forest Service, it is a greening and food production program that operates with local groups to plant, maintain, and harvest fruit- and nut-bearing trees, shrubs, and vines on public land. South Central Farmers, a collective of 350 or so low-income and largely Latino immigrant families in South Central Los Angeles, has received national publicity in its struggles to hold on to the fourteen-acre farm that the city has sold from underneath them. One of the largest urban and communal farms in the US, its occupants were forcibly removed by the sheriff in June 2006; forty people were arrested.

The ejection of the community gardeners conjures a much older event in the history of property and its use—the enclosure of the commons that began after the Renaissance and took full steam during the Industrial Revolution. Commons were found in many pre-industrial societies and were used for grazing, communal farming, woodcutting, and fishing. The principle was that though common land might be owned by towns or individuals, the right to its resources or its use was shared by the community. Examples of rights of common are common piscary (the right to fish), estovers (the right to take sufficient firewood) and common pasture (to graze one’s animals); communal plantings were necessary because plowing and farming were so labor-intensive. The legal position concerning the commons is ambiguous, as most commons were based on ancient rights that predate formal law and any form of government. Most Scandinavian countries still permit public lingonberry and cowberry harvesting on uncultivated private land, and hunting game on private land is permitted (with a license) in countries all over the world.

Food has always provided the most ancient forms of communion among people. Hunters and gatherers banded together for survival, and gatherers became farmers; farming laid the ground for humans’ connections to the earth, and farms became the first communities. Among all the foods, fruit holds a special place as a symbol of bounty, fertility, beauty, and hospitality, which is perhaps why of all foods we most like to give fruit as a gift. The gift model—giving without expectation of return—forms the basis of the public fruit project, re-territorializing urban space with a sort of residual slippage of control and restrictions.

Matias Viegener is a member of Fallen Fruit, a Los Angeles-based artist collective.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.