Inventory / Artist’s Impact

Naming Mercury’s craters

Mats Bigert

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

In November 1973, Mariner 10, an unmanned robotic interplanetary probe, was launched from NASA’s space center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. One of its missions was to capture images of Mercury, a planet whose proximity to the sun had made it one of the most difficult to observe. In fact, Mercury’s elusive nature and ability to escape the scrutiny of astronomers is why the Romans named it after the fleet-footed god. After a yearlong trip, Mariner 10 made three successful flybys of Mercury and sent back a vast number of images showing a chaotic, moon-like surface complete with craters and ridges. Unfortunately, the probe’s camera only managed to capture roughly forty-five percent of the planet’s surface before it burned up, like an Icarian moth flying too close to the sun.

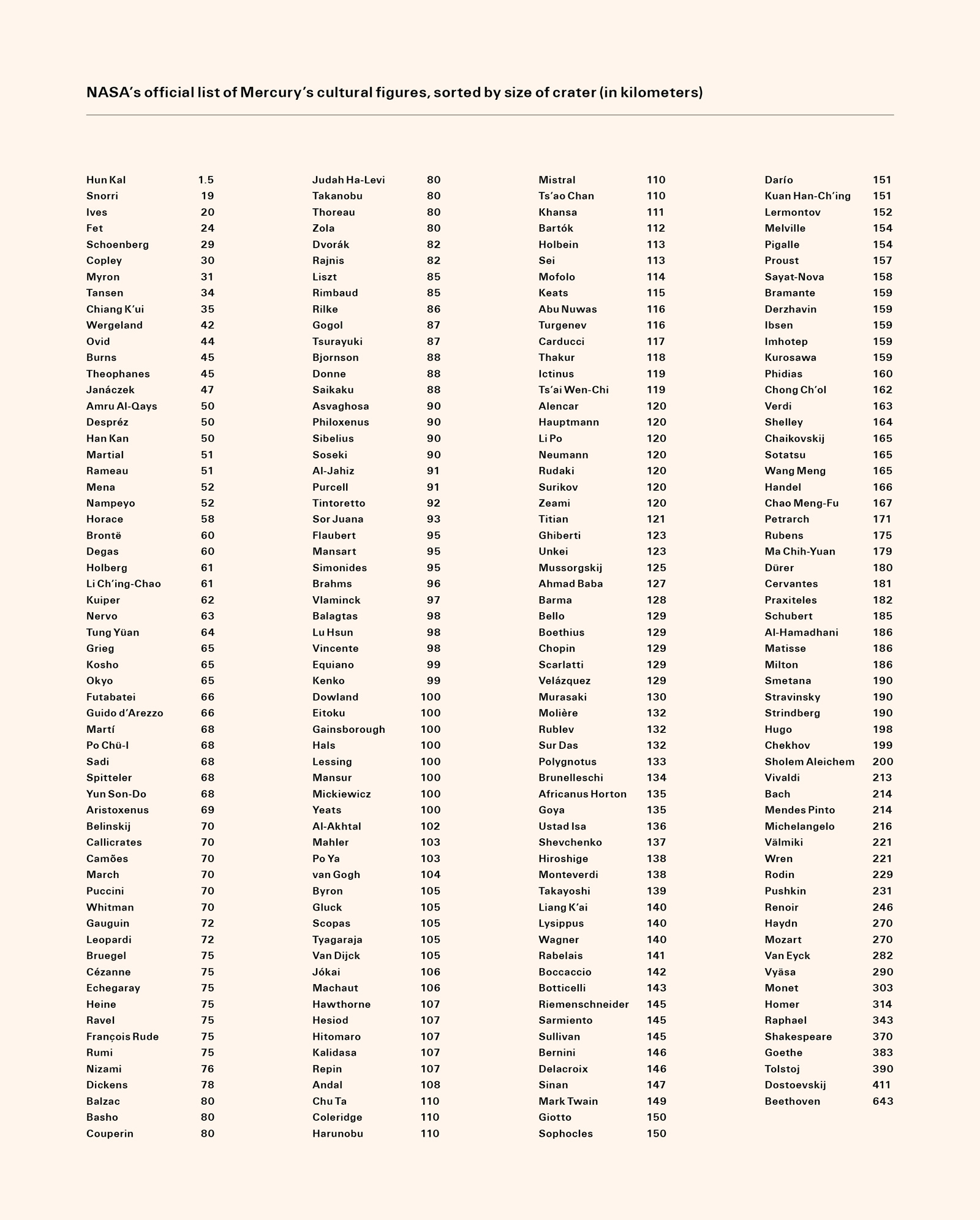

The year of Mariner 10’s launch was also the year in which the International Astronomical Union (IAU) set up the Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). Subgroups working under the auspices of the WGPSN were each assigned the task of naming features on a specific planetary body in the solar system. If approved by the WGPSN, these names were then passed on to the IAU and adopted at an IAU General Assembly. The group responsible for naming all of Mercury’s features, including its ridges, mountains, valleys, and plains, was chaired by David Morrison, currently senior scientist at the NASA Astrobiology Institute. By the time Morrison’s group had finished its work, every crater on Mercury had been named after an influential artist, composer, or writer (see page 10 for the entire list of names sorted by size of crater). Mats Bigert emailed Morrison to find out how the Mercury Task Group made its decisions.

Cabinet: How was the Mercury Task Group formed?

David Morrison: The WGPSN asked me to chair it, and I suggested the other task group members, with due concern for broad international membership. Most of the nomenclature work was done in less than twelve months.

Who came up with the idea of naming the regions and craters on Mercury after famous writers, composers, and artists?

I think I did. In any case, I certainly pushed “cultural heroes” among the various options considered for the craters. Other categories that were suggested for crater names included birds and butterflies, in addition to scientists, as were already being used on the moon and Mars.

The list of artists is very extensive, both geographically and historically. How were these names assembled?

We drew on various encyclopedias and reference books to create a name bank with broad international representation. There were also specific recommendations from team members, especially from the Russians and Chinese. We also sent letters or made calls to a few scholars. I did this to make sure we represented Persian and Arab artists, for instance, who were less familiar to us. It would be a lot easier today with Google!

How did you decide which crater would be assigned to which artist? How, for instance, did Strindberg or Botticelli get their specific craters?

I generally tried to pick the most famous people for the biggest craters, always seeking to maintain an international balance. Since we were naming features on only about half of Mercury, we tried to use only about half of the most prominent names.

Were some artists ejected from the list for being, say, too subversive or too “unknown”?

Not many. As I recall, two of my composer suggestions—Gilbert & Sullivan and Scott Joplin—were vetoed.

Which artist names were “left over” after all the craters were taken?

Since only half the large craters have been named, we made no effort to be complete—only representative.

Two people—Kuiper and Hun Kal—stand out as non-artists. Who were they?

Both these craters were named in early Mariner 10 approach photos, before our task group started its work. Gerard P. Kuiper was the greatest mid-century planetary astronomer, and Hun Kal is actually the Mayan word for twenty, marking the twentieth meridian on Mercury (which serves the same purpose as the Greenwich Meridian on Earth).

According to the Mercury map in the NASA Space Atlas, the planet has been divided in three regions: the Shakespeare region, the Bach region, and the Renoir region. As far as Shakespeare and Bach are concerned, I have no objections given their major impact in their respective art forms. But as a visual artist myself, I have to say that I’m more than puzzled by the choice of Renoir as the ambassador for the visual arts. How was the decision made to give Renoir a whole region of Mercury?

This was a mapping issue, not a nomenclature decision. Map sections (for Earth also) are always named after their most prominent feature.

The gender question doesn’t seem to have been on your agenda during that time. Male dominance on Mercury is almost total. Why is that?

As you say, not on our agenda. We were much more concerned about multicultural issues.

If the Messenger mission flyby of Mercury in 2011 is successful in photographing the previously unmapped side of the planet, will the gender imbalance be countered by giving the other side exclusively to women artists?

I doubt it. But I anticipate that we will use more women’s names than before.The original article misstated the dimensions of Mercury’s craters by a factor of a thousand; the unit given should have been kilometers rather than meters.

Mats Bigert is an editor-at-large of Cabinet and one half of the Swedish artist duo Bigert & Bergström. A solo exhibition of their work took place in summer 2007 at the Uppsala Art Museum, Sweden. Bigert & Bergström are currently at work on a film, premiering worldwide in 2008, that addresses the utopian quest for immortality.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.