Mark of Integrity

A brief history of card tricks

Jonathan Allen

In the preface to S. W. Erdnase’s classic treatise on “professional” card handling, The Expert at the Card Table (1902), the author suggests that the volume may “inspire the crafty by enlightenment on artifice” and enable someone “skilled in deception to take a post-graduate course in the highest and most artistic branches of his vocation.”[1] Stated more clearly, the volume is a practical guide for card cheats.

Erdnase’s identity remains to this day a matter of controversy, but what is certain is that the book’s author knew the world of fin de siècle cardsharping intimately, and had strong opinions about what he had seen.[2] The Expert focuses on “card mechanics,” the physical mastery of card manipulation. Shifts, culls, and blind riffles are dealt out in functional detail alongside jogs, slides, and false shuffles. Erdnase sharply contrasts these and other “artifices” with what he condemns as “advantages without dexterity,” examples of which include collusion at the card table, the employment of doctored playing cards, and the use of “hold outs” (cumbersome mechanical gadgets that enable useful cards to find their way secretly into the operator’s hand).

The distinction he draws—between enlightened professionals and artless amateurs, whose “skill, or rather want of it,” requires the use of such inexpert methods—lends the book its sardonic edge, since its rhetoric never fully conceals the fact that no matter how elegantly he might conduct his art, the “professional” is just as much of a crook as his amateur counterpart. If we set aside, however, a hierarchy of deception based on methodological differences and stylistic proclivity, we are free to consider in greater detail one of the “advantages” that Erdnase dismisses and to observe a history of deviousness that, far from wanting in dexterity, simply demonstrates its application in different, if not more subtle, ways.

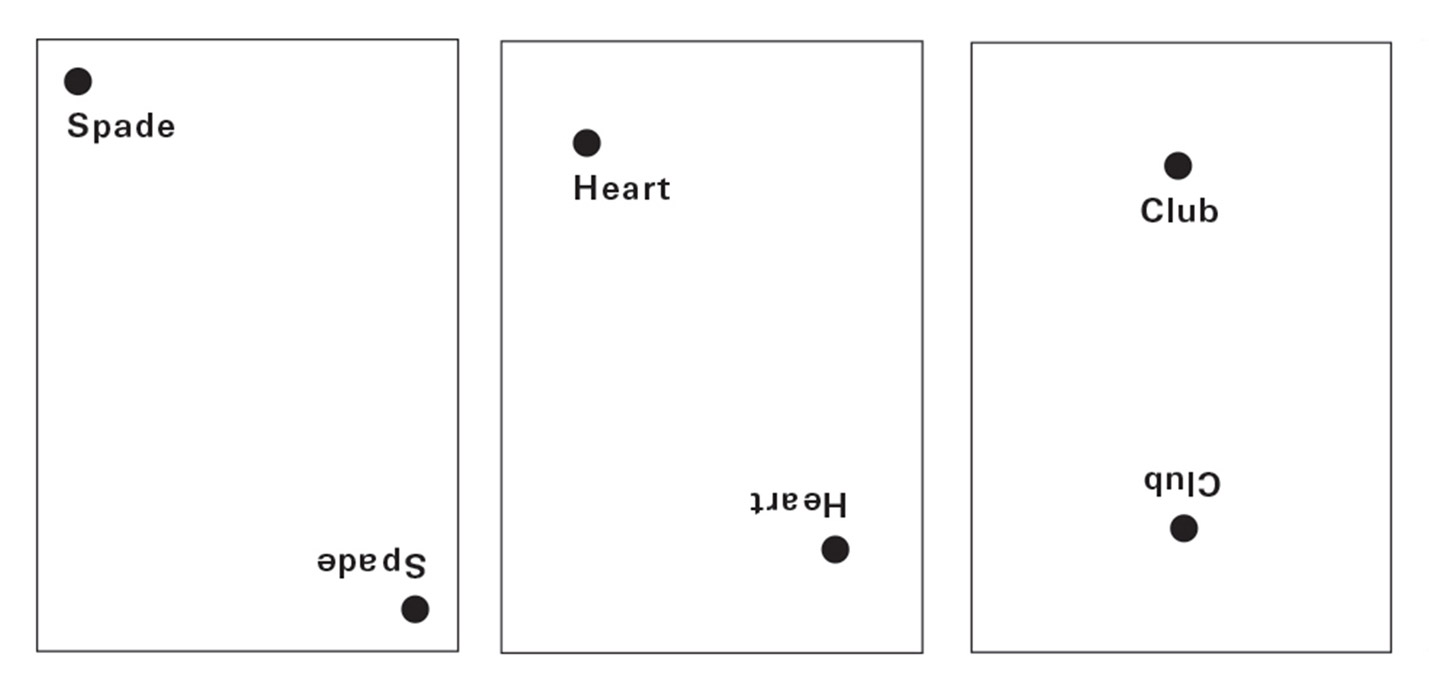

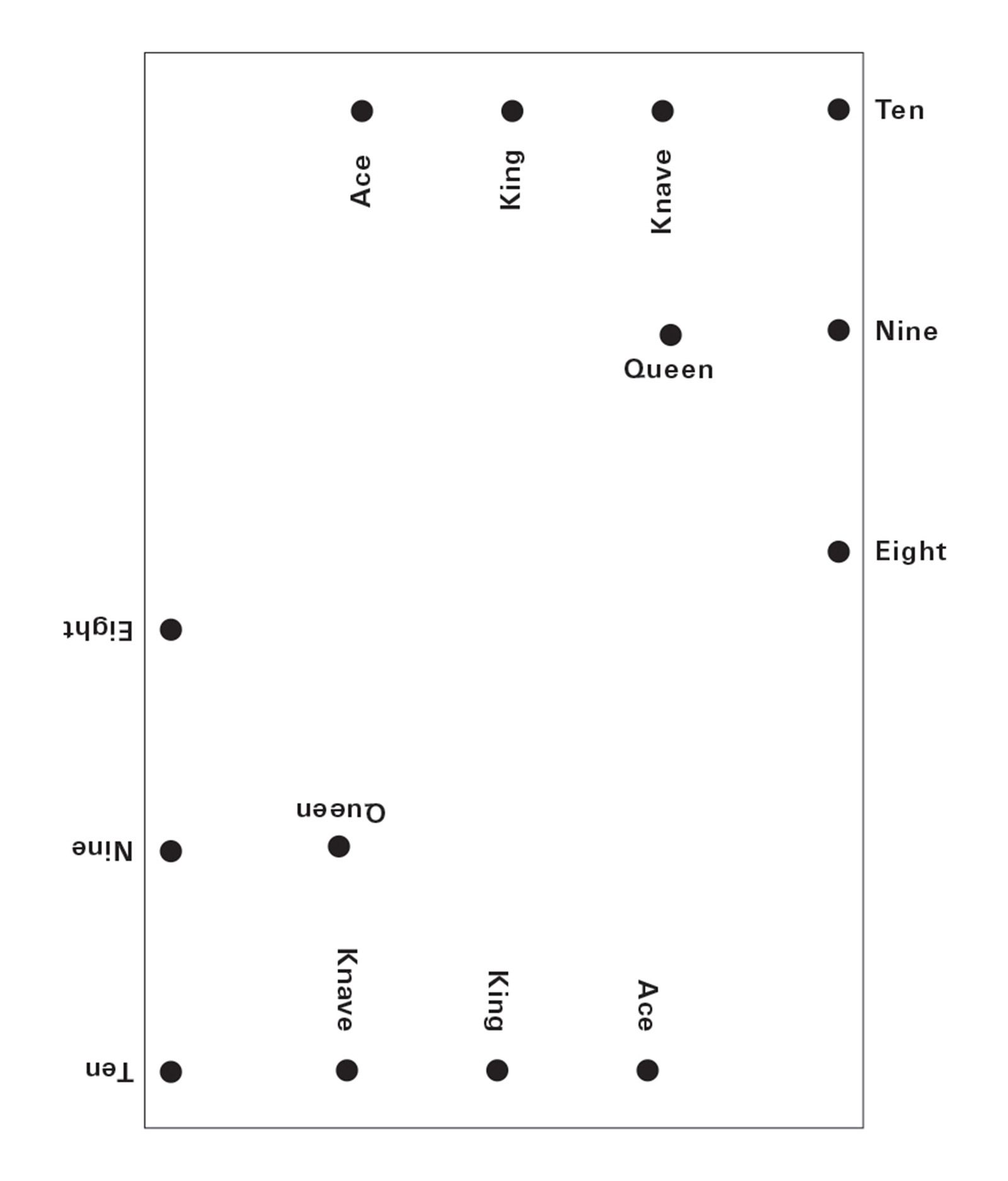

The history of the marked playing card, perhaps as old as the playing card itself, is a miscellany of inventive guile. “The systems of card-marking are as numerous as they are ingenious,” wrote John Nevil Maskelyne in 1894. “Card doctoring,” to use Erdnase’s term, covers many forms of subterfuge, but in the brief survey that follows, we shall focus our attention upon what might more usefully be termed the “language” of the marked card.

One of the many early documents to describe card marking refers to a system in which cards are divined not by a visible mark but through touch. In his recent commentary on Horatio Galasso’s Giochi di carte bellissimi di regola e di memoria (1593), historian of magic Vanni Bossi describes Galasso’s methods: “The secret involved is the covert marking of cards by nail-nicking or punchwork (using a metal point: un punctal de strenga). … By dealing through the deck, the performer can, with ‘the fleshy tips of the fingers,’ tactilely locate the marked cards without looking at them.”[3]

The rudimentary punched cards described by Galasso in late sixteenth-century Italy had become les cartes pointées (pricked cards) by the time they were documented by Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin in Les Tricheries des grecs dévoilées in 1863. The term grec (Greek), used as shorthand for “cardsharp,” draws on a long history of prejudice which Robert-Houdin reflects in his description of “Greeks [who] improve on this method by splitting apart the corner of the card, making the puncture from the inner surface, and afterwards pasting the two surfaces together again. In this way, nothing is to be seen but a slight roughness on the back of the card, which, should it ever be remarked, would pass for a mere defect in the card-board.”[4]

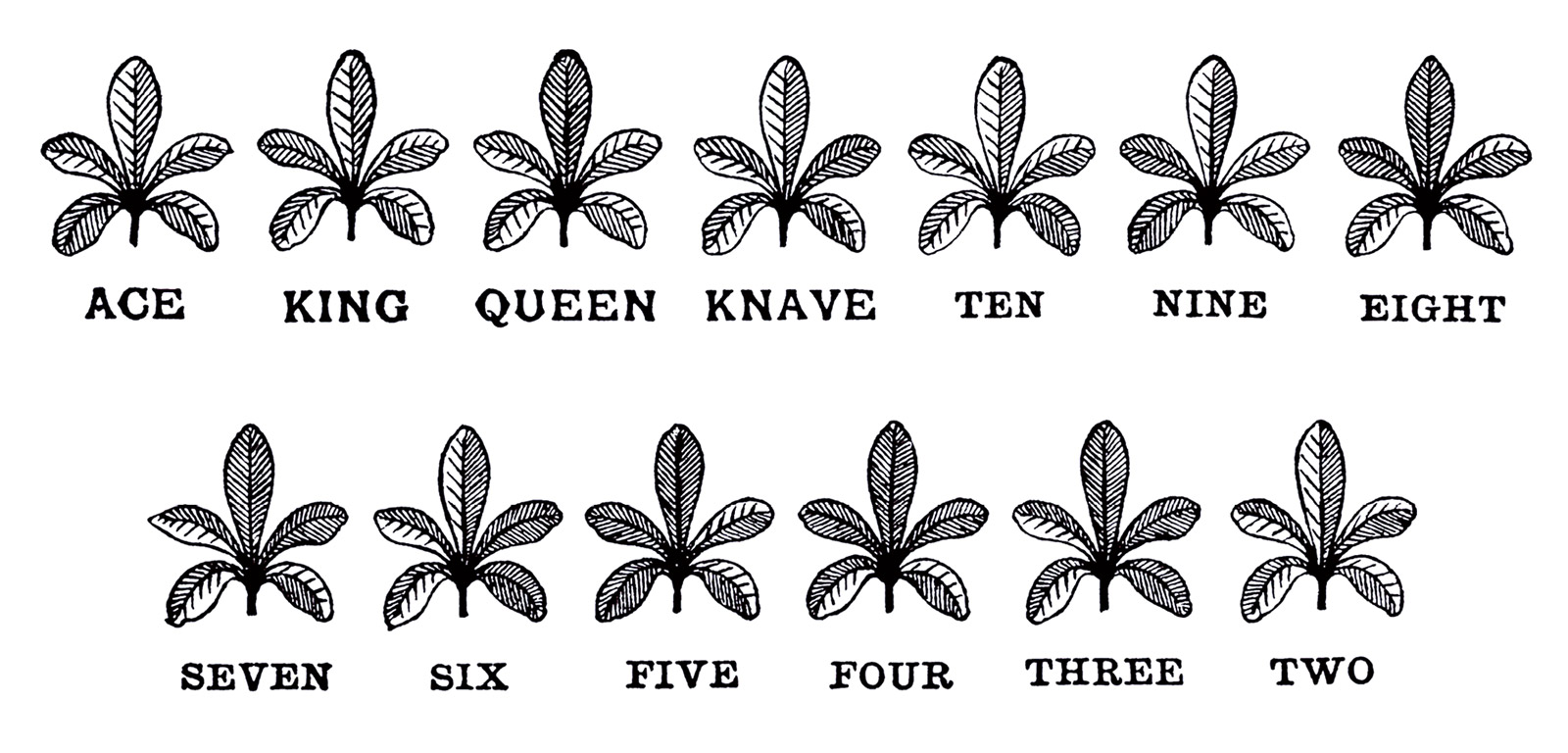

Sometime during the same century, card pricking became further codified in the hands of an enigmatic French card-worker known simply as Charlier.[5] The “Charlier system” allowed piquet cards to be read through a sophisticated code of ponctuation (punctuation) set out clearly by Professor Hoffmann, magic’s most influential writer of technical manuals, in More Magic (1890). The Magic Circle in London has in its archives a deck marked by Charlier himself, a personal gift to Hoffmann from the Frenchman, who vanished in London in 1882, never to reappear.[6] Nailing and punching (later known also as blistering or pegging) continue, with mixed success, to evade detection to this day, both in the theatrical magic world and general card play.

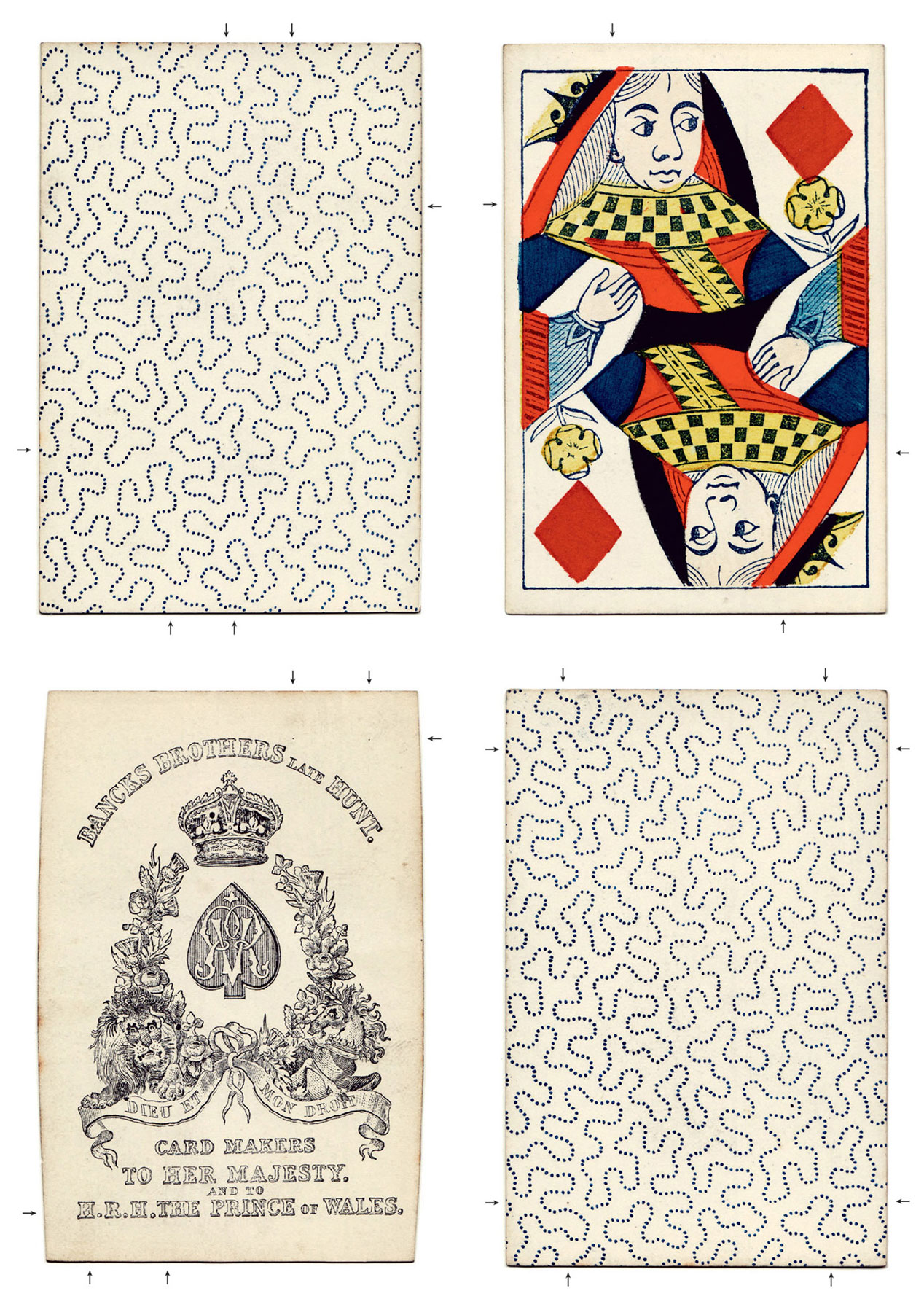

As for visual card marking, the simplest and most widespread method is probably daubing, which does not require advance access to the deck: the adept merely smudges the back of relevant cards with a tiny indicative speck of ash or dirt as play unfolds. It was partly in order to combat the ability of early cardsharps to daub plain or simply patterned card-backs that complex back designs flourished. But these new designs, while rendering the dauber’s mark less legible, ushered in card marking’s golden era by providing innovators with a vast range of figurative and abstract geometric decoration upon which to practice their art.

Although the subtle alteration of card-back design features in many of the earliest accounts of card mischief, the most comprehensive treatment of this form of marking can be found in Sharps and Flats: A Complete Revelation of the Secrets of Cheating, published in 1894 by magician John Nevil Maskelyne.[7] In a section whose pages could be mistaken for those of a neo-classical decorative arts manual, Maskelyne shows how miniscule adjustments to the motifs found within the card-back designs of his time allow their face values to be determined at a glance. Two main stylistic groupings emerge: shading and tint-work, and line-work and scrollwork. Shading involves the almost imperceptible darkening of a tiny selection of a back’s design, whereas tinting amounts to shading-in-reverse, whereby the entire card-back is slightly darkened except for marked sections. Line-work and scrollwork take advantage of the rococo ornaments common to many back designs by selectively adding to, or otherwise altering, curlicues, fronds, and other compliant motifs.[8]

Maskelyne spends considerable time discussing decks that are marked during manufacture but, in keeping with later commentators, notes that mass-produced marks become common knowledge too rapidly to sustain their effectiveness.[9] A “paper-worker,” according to Frank Garcia in Marked Cards and Loaded Dice (1962), prides himself on the secret markings he has personally applied; indeed, another term used to describe a paper-worker is “painter” because the latter prefers to “paint his own paper.” To this day, cardsharping instruction includes detailed advice on inks, brushes, solvents, and varnishes to uphold the cardsharper’s motto, “Art is to conceal art.”[10]

However, even the most proficient card-painter becomes vulnerable to detection if the deck is riffled, whereupon the changing marks can be seen to move about as in a miniature flick-book animation; this interrogatory process is known as “watching the movies.” Just as cinema finally loosened painting’s hold on representation at the beginning of the twentieth century, these miniature “movies” diminished the card-painter’s presence at the game table, thus curtailing card marking’s most representational, if not baroque, era.

Card marking’s more recent époques have been characterized by the pursuit of even greater deceptive invisibility. Three earlier systems that employed quasi-abstract methods have passed into gambling folklore. “Sunning the deck” involved marking high-ranking cards by leaving them in harsh sunlight to yellow slightly, while the simple process of spilling water on selected cards during play (producing extremely faint drying marks) had the additional advantage of a credible alibi if discovered. “Ironing the deck” involved just that—using sufficient heat to dull the varnish luster of selected cards. But if these methods tend toward the mundane, then some variations in the last quarter of the twentieth century have compensated with a distinctly otherworldly character.

“Luminous readers” are cards treated in such a way that pale green ink traces become clearly visible when viewed through red-filtered spectacles or contact lenses. The technology caused alarm upon its discovery but, due to its limited effectiveness and its reliance upon somewhat vampiric eye adornment, has remained more of a popular novelty than a serious subterfuge.[11] “Juiced cards,” on the other hand, do not need lens-based viewing, instead requiring the reader to defocus his or her eyes and spot liminal fluid-residue marks on an opponent’s distant cards (juiced cards are also known as “distance readers”). To many players, juicing, and its recent high-tech offshoot, “video juicing,” are the most effective real-world card-marking system available, and the considerable price of the closely guarded fluid recipe and application technique reflects this growing reputation.

With the advent of online gambling, card marking’s passage into abstraction was complete: a digital deck cannot be marked. Or can it? The software that has replaced the physical playing card has turned out to be as vulnerable as its material antecedent. When mathematically minded players on the UltimateBet gaming site noticed in early 2008 that account holders such as the now infamous “NioNio” were winning hands at rates sometimes ten times beyond standard deviation, the owners of the site were forced to concede that some players did enjoy an unfair advantage secured through “unauthorized software code that allowed the perpetrators to obtain hole card information [the identity of face-down cards] during live play.”[12] In a scandal that continues to shock the online gambling community through its wide-ranging network of suspected collusion, it has emerged that the software in question was designed several years previously through a consultation process with high-ranking professional players whose expertise was sought in order to develop online gambling sites that were “true to the game.”[13]

- This book was originally published in 1902 under the title Artifice, Ruse, and Subterfuge at the Card Table: A Treatise on the Science and Art of Manipulating Cards. The original binding bore the title “The Expert at the Card Table,” by which the book is now commonly known.

- Reversed, S. W. Erdnase spells E. S. Andrews, a realization that has triggered a number of countering claims upon Erdnase’s true identity. Martin Gardner, David Alexander, and Richard Hatch have made cases for the following identities, respectively: Milton Franklin Andrews, Wilbur Edgerton Sanders (W.E. Sanders is an anagram of S. W. Erdnase), and Edwin Summer Andrews. The literal German translation of erdnase is “earth-nose,” which some have seen as significant. Most controversy, however, focuses on the erudite literary style of the book, which contrasts with the levels of literacy more common among cardsharps of the era and has led to suggestions that a ghostwriter was involved. The Expert at the Card Table was central to A Man in a Room Gambling (1997), a sequence of five-minute texts with music by composer Gavin Bryars and artist Juan Muñoz.

- Vanni Bossi, “Commentary on Galasso’s Giochi di carte…e di memoria,” in Gibecière, vol. 2, no. 2 (Summer 2007), p. 166, translation of Galasso from Italian by Lori Pieper. The title of Galasso’s book, published in Venice in 1593, translates as “Most Beautiful Card Games Based on Rules and Techniques of Memory.” Bossi speculated that punchworked playing cards might have played a part in the evolution of Braille. Following this speculative line, one might ask whether Charles Barbier de la Serre (a key figure in Braille’s history) encountered a pricked deck amongst his fellow soldiers during the Napoleonic Wars, leading him to develop his dot-and-dash-based “night writing.” The latter was a Braille-like script designed to prevent soldiers from rendering themselves vulnerable to opportunistic gunfire as they used lamplight to read tactical missives. Magician, writer, and historian Vanni Bossi, who contributed personally to the evolution of this article, died in December 2008 and will be greatly missed.

- Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, Card-Sharping Exposed (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1890). The use of the term “greek” to describe a cardsharp may have its origins in stories of a renowned and highly successful Greek card cheat, Theodoros Apoulos, active during the reign of Louis XIV. The more long-standing prejudicial labeling of a deceitful person as a “greek” may also reflect Schistic animosity between the Orthodox eastern Roman Empire and the Roman Catholic western Empires.

- See Sydney W. Clarke, The Annals of Conjuring, edited by Edwin A. Dawes and Todd Karr in collaboration with Bob Read (New York: The Miracle Factory, 2001).

- The paper wrapping in which the deck was delivered to Hoffmann was signed “To Monsier J A Louis Advocat,” an ironic reference to Hoffmann’s professional status as a lawyer. Hoffmann’s real name was Angelo John Lewis (1839–1919).

- An early account of card marking can be found in Gilbert Walker’s A Manifest Detection of the Most Vyle and Detestable Use of Dice Play from 1552: “Lo is there much discept in it, some play upon the pricke, some pinch the cards privily with their nayls, some turne up the corners, some mark them with fine spots of inke.” And the uncredited Hocus Pocus Junior–The Anatomy of Legerdemain from 1654 states: “Moreover for the Cards there are divers other tricks, of which those that are cheaters make continual practice, as nipping them, turning up one corner, marking them with little spots, placing glasses behind those that are gamesters, and in rings for the purpose, dumb shows of some standers by.”

- Card marking’s vast and fugitive lexicon signals an educative endeavor among a community united in secrecy. Other terms include “block-out work,” “edgework,” “humping,” “white-on-white,” “sandwork,” and “crimping,” to name just a few. Frank Garcia, author of Marked Cards and Loaded Dice, uses the terms “chemists and cosmeticians” since some techniques use mildly odorous materials. A term in current use online is “inking.”

- While individual examples exist of decks marked during manufacture and distributed to gambling houses, there is a recurring grand conspiracy theory that all cards are marked in production, thus “revealing” a pan-global conspiracy between card manufacturers, gambling companies, cardsharps, and financial institutions.

- John Nevil Maskelyne, Sharps and Flats: A Complete Revelation of the Secrets of Cheating (London: Longmans Green, 1894), p. 25. In contrast to the permanent deceptions (from the Latin verb decipere, to ensnare or cheat) of the cardsharping “painter,” the theatrical magician employs the same methodology to different aesthetic ends by instigating an essentially ludic encounter with the audience (illusion, from the Latin verb ludere, to play). For the magician, like the artist, deception remains in the service of the production of the conditions of propositional illusion.

- In February 1961, the New York State Commission of Investigation reported on syndicated gambling in the state, and revealed a growing market in luminous card reading accessories such as “New Improved Triple Curved Contact Lenses.” See Frank Garcia, Marked Cards and Loaded Dice (New York: Bramhall House, 1962).

- Mike Brunker, “Poker site cheating plot a high-stakes whodunit,” msnbc.msn.com/id/26563848/ [link defunct—Eds.]. Accessed 18 September 2008.

- Max Drayman, “UltimateBet Online Poker Interview,” winneronline.com/interviews/ultimatebet.htm [link defunct—Eds.]. Accessed 9 February 2009. In the interview, the spokeswoman for ieLogic, the software developers of UltimateBet, boasted that “UltimateBet is lucky to have so many world poker champions choose to be a part of our project. ... [They] have helped us develop a site that is true to the game.”

Jonathan Allen is a London-based artist and writer. He was the Arts Council England Helen Chadwick Fellow for 2007–2008 at the University of Oxford and the British School at Rome, and is currently co-curating a Hayward Gallery National Touring exhibition with Sally O’Reilly. For more information, see www.jonathanallen.info.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.