A Child Could Do It

The art of aesthetic ability testing

Tom Holert

In the first half of the twentieth century, the academic psychological community did not hold the field of art psychology in particularly high esteem. Researchers engaged in such studies were consistently faced with snobbery and disregard from colleagues using more established approaches to measure the human mind. However, in Europe and the US in the 1920s and 1930s, an ever-growing demand for biopolitical tools for assessing all aspects of individuals’ abilities, aptitudes, and personalities—combined with the role the discourse of “creativity” had increasingly played in educational reform since the turn of the century—resulted in greater attention to the aesthetic capacities of the individual.

In the US, experimental psychologists of a certain, albeit parochial, renown like Alfred S. Lewerenz, E. L. Thorndike, Florence L. Goodenough, or G. L. Carey developed tests to measure all kinds of artistic abilities. They took their cue from earlier diagnostic studies on the correlations between drawing and manual, as well as mental, skills by researchers such as Wilhelm Wundt, Georg Kerschensteiner, and Ernst Meumann. To allow the “scientific” investigation of childhood talent and the subsequent placement of such talent in the educational and vocational realm of the Fordist regime of production, American psychologists devised tests including “Measuring Scale for Free-Hand Drawing,” “Scale for General Merit of Children’s Drawings,” “Art Aptitude,” and “Art Appreciation.”

Between 1929 and 1939, Norman C. Meier, an associate professor in the psychology department at the University of Iowa and one of the major proponents of the tiny sub-discipline of psychology known as “psychology of art,” directed a research program called “Genetic Studies in Artistic Capacity” with support from the Spelman Fund and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. At times, Meier’s funding was so generous he could afford to employ up to twenty research assistants. Based on the findings in his 1926 University of Iowa dissertation, “The Use of Aesthetic Judgment in the Measurement of Art Talent,” the main hypothesis of the ten-year program came close to being tautological. Meier’s position was, as he explained in the 1933 introduction to the first volume of “Studies in the Psychology of Art” (which he edited for the American Psychological Association’s prestigious “Psychological Monographs” series), “that aesthetic sensitivity, measurable through aesthetic qualities or principles of art, constitutes the most certain index to artistic capacity.”[1] Likewise, he discovered that cognitive capacity, as measured by intelligence testing, was linked to artistic success.

Though eager to display his comprehension of that segment of contemporary art he dubbed “experimental art,” which he acknowledged as the “laboratory of art in general,” Meier’s steadfast belief in anthropologically constant “principles” was not exactly sympathetic with modernist trends of his time. As he states in Art in Human Affairs: An Introduction to the Psychology of Art, his 1942 summary of more than fifteen years of research into the hereditary and environmental determinants of “artistic aptitude,” individuals may differ in their “evaluative behavior,” but “change in the fundamental bases of evaluation is not considerable.”[2] Meier’s aesthetic principles placed art’s value beyond the effects of historical change. There was “normality” and “abnormality” in nature; these manifested themselves as “ordered, contrasted, organized presentation,” on the one hand, and “the confused statement, the rambling argument, the unmatched measure, or the non-climactic drama,” on the other.[3] The decision as to what is preferable was made long ago, at an early stage in the evolution of the human capacity to produce and behold artworks.

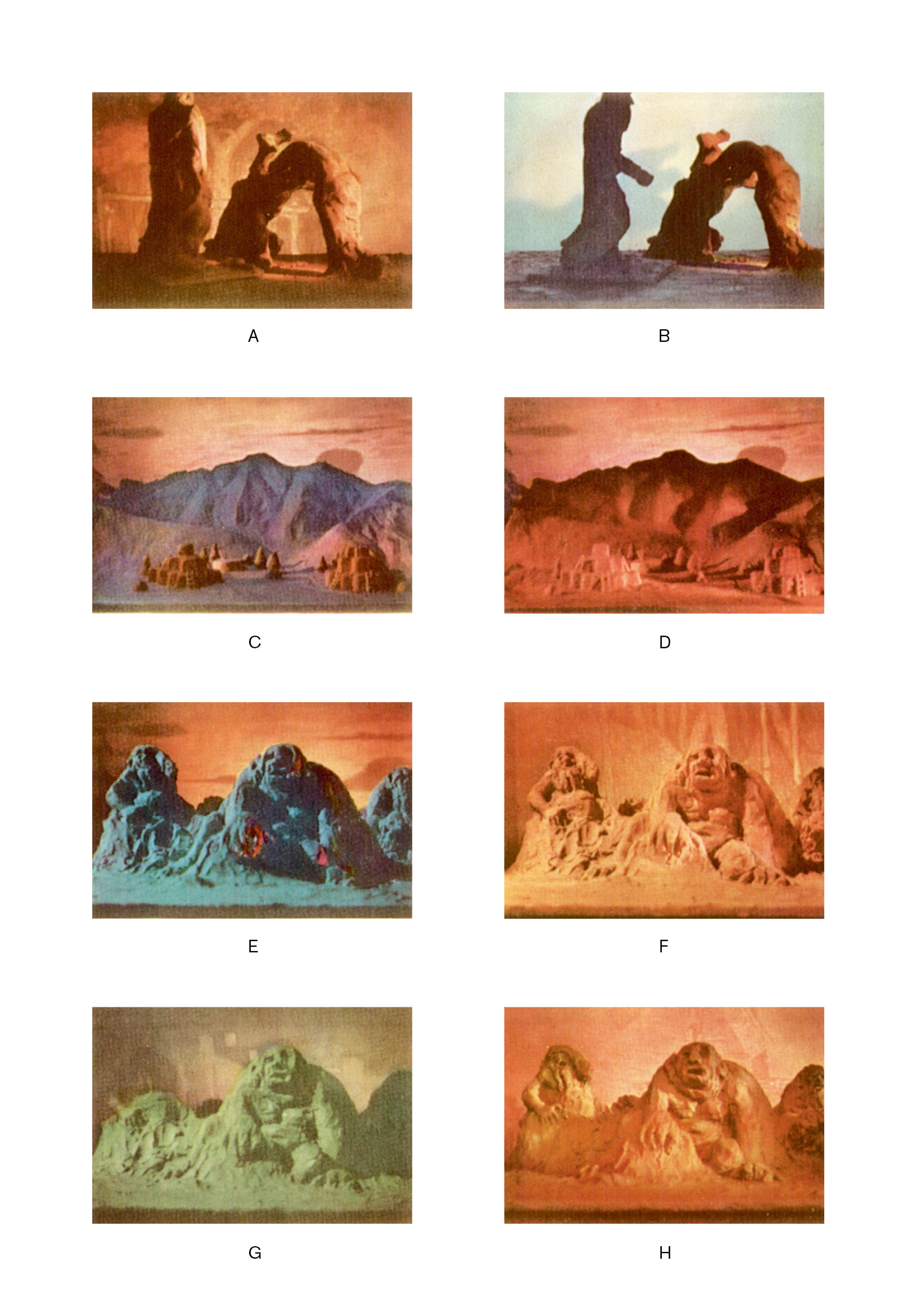

In the “Meier-Seashore Art Judgment Test,” published by Meier and his mentor Carl E. Seashore in 1929, subjects were asked to select the “better (more pleasing, more artistic, more satisfying)” from two pictures. The test booklet consisted of 125 pairs of pictures, each of which consisted of an image of “recognized artistic merit” and the same image altered “to lower its artistic excellence.”[4] The aim was to identify the gifted child who shows evidence of manual skill, energy, aesthetic intelligence, perceptual facility, and creative imagination. Unsurprisingly, the strictly binary right/wrong conceit of Meier’s test left no room to register the unexpected.

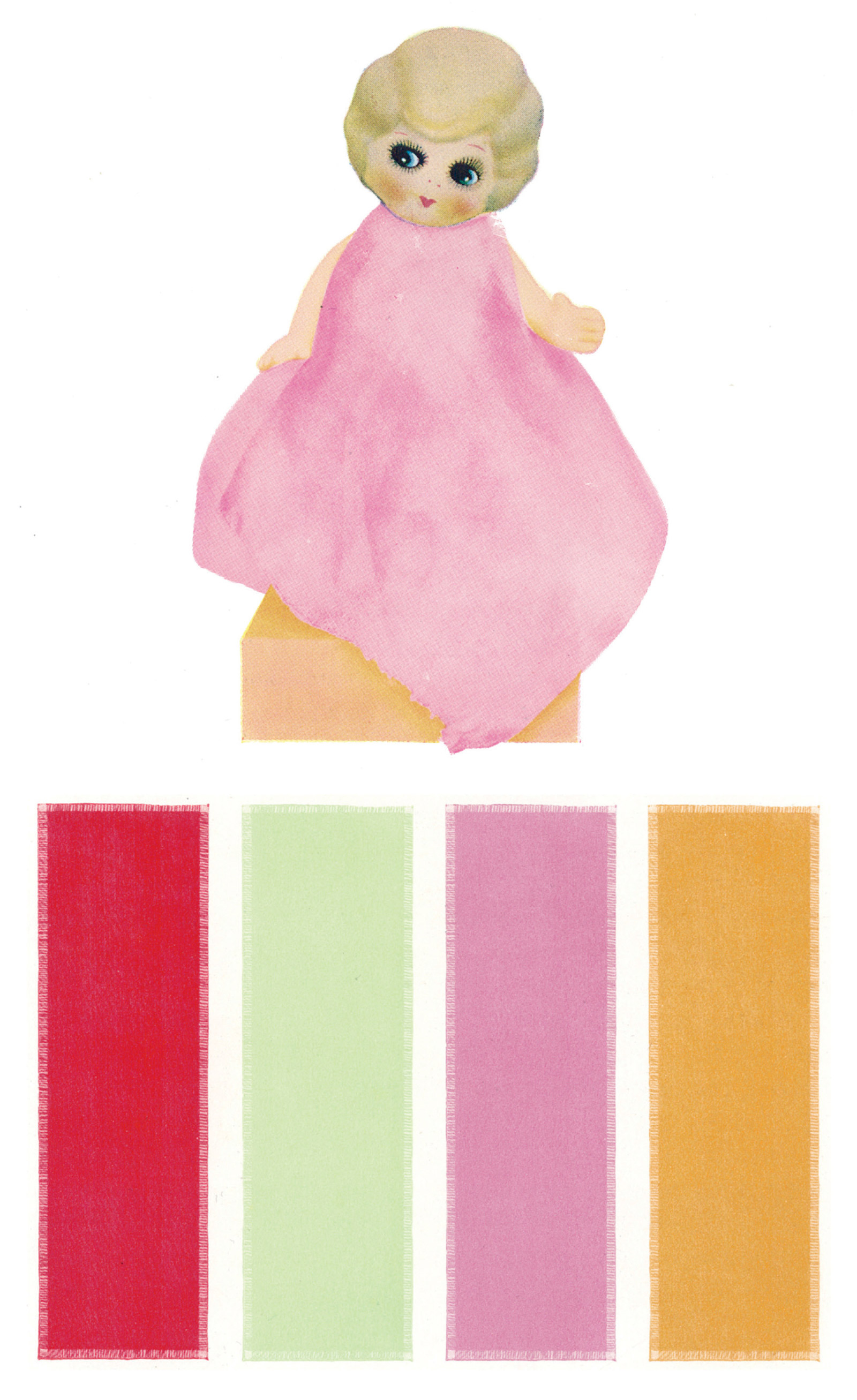

Accounts of Meier’s psychology of art course in the 1940s similarly speak of an art lover who loved art as long as it followed his ideas of harmony, symmetry, and balance. “I sometimes wondered if the project ever managed to get away from the hard-boiled test concept,” Eileen Jackson Williams said half a century later of her Iowa years.[5] In the early 1930s, Williams conducted a study at the Iowa State Teachers College Elementary School for “testing color harmony sensitivity in young children,” using a doll and the Ridgway system of “color standards and color nomenclature.”[6] The preschool children were asked to drape a scarf made of sateen around the already dressed doll, selecting from among four options. The color of one of these scarves was deemed complementary to the hue of the doll’s dress, and the children’s aesthetic “judgments” received high scores when they chose this “good” dress-scarf combination, as opposed to a “poor” match.

Various shortcomings marred the construction of this particular test, however, because it lacked a scientific basis in color theory and was instead to be calibrated according to adult consensus. Whether such consensus was in fact achievable was a cause of considerable anxiety for the researchers: “It was therefore necessary to use some means to distinguish the better from the poorer situations. One way considered was to get judgments from art teachers or similarly qualified persons. This required that they be carefully instructed to keep the situation abstract.”[7]

This “abstraction,” defined as the absence of other chromatic distractions, was judged crucial not only for producing consensus among the teachers, but also for creating the most favorable conditions for the test-taking toddlers: “All tests were given between 9 and 11:30 A.M. in a small room with northern sky light. The walls were of unpainted white plaster. E [i.e., Eileen Jackson Williams] and the subject sat in front of a small table which was covered with neutral paper. E wore a white uniform, so that the child’s own clothing furnished the only possible source of suggestion in regard to color combinations.”[8] But this white cube laboratory was not reproduced as faithfully as had been proposed. In a black-and-white photograph accompanying the description of the procedure, the female test instructor is wearing a patterned dress of which only the collar is white, and in the background, behind the boy being tested, a dark curtain also invades the neutrality of white. Nonetheless, the aesthetics of psychological abstraction do dominate this picture, and even more so a color plate adorning the same article. Here, rather than a physical object, an image of a rather idiosyncratically designed doll hovers above four strips of color, one of which was again to be chosen to match the doll’s dress. This linking of the realist allure of the doll’s image and the functional aesthetics of testing is probably the closest Williams ever came to “abstracting” the testing of children’s aesthetic aptitude. The doll appears to be waiting for the moment when she is to be involved in the test—when she is to be dressed in near-modernist stripes of color, matching or mismatching, and thus, according to the schemes of Dr. Meier, signifying artistic success or failure, talent or its lack.

- Norman C. Meier, “Introduction,” in Psychological Monographs, vol. XLV, no. 1, 1933, v.

- Norman C. Meier, Art in Human Affairs: An Introduction to the Psychology of Art (New York and London: McGraw-Hill, 1942), p. 83.

- Ibid.

- Madaline Kinter and Paul S. Achilles, The Measurement of Artistic Abilities: A Survey of Scientific Studies in the Field of Graphic Arts (New York: The Psychological Corporation, 1933), p. 14.

- Quoted from Marilyn Zurmuehlen, “Questioning Art Testing: a Case of Norman C. Meier,” in Gilbert Clark, Enid Zimmerman, and Marilyn Zurmuehlen, Understanding Art Testing: Past Influences, Norman C. Meier’s Contributions, Present Concerns, and Future Possibilities (Reston, VA: National Art Education Association, 1987), p. 66.

- Eileen Jackson Williams, “A Technique for Testing Color Harmony Sensitivity in Young Children,” in Psychological Monographs, vol. XVIII, 1933, pp. 46–50; Robert Ridgway, Color Standards and Color Nomenclature (Washington, DC: Ridgway, 1912).

- Eileen Jackson Williams, “A Technique for Testing Color Harmony Sensitivity in Young Children,” op. cit., p. 48.

- Ibid., pp. 49–50.

Tom Holert is a Berlin- and Vienna-based art historian who teaches and conducts research at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna. His books include Fliehkraft: Gesellschaft in Bewegung—von Migranten und Touristen (with Mark Terkessidis; Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2006), Marc Camille Chaimowicz: Celebration? Realife (Afterall/MIT Press, 2007), and Regieren im Bildraum (Polypen/b_books, 2008). He is currently working on a study of modernist art and culture and experimental psychology.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.