All Monsters Must Die

Gojira’s children go to North Korea

Magnus Bärtås and Fredrik Ekman

After crying himself to sleep, the little prince wakes up the next morning with a heavy heart. His father—the king—is dead, poisoned by the power-hungry black knight El El. Before dying, the king had managed to pass along a valuable gift to his son, a little stone sculpture of a strange creature he called Galgameth. The prince’s streaming tears fall on the sculpture, and later, while the prince sleeps, the figure comes to life in a little cloud of stardust.

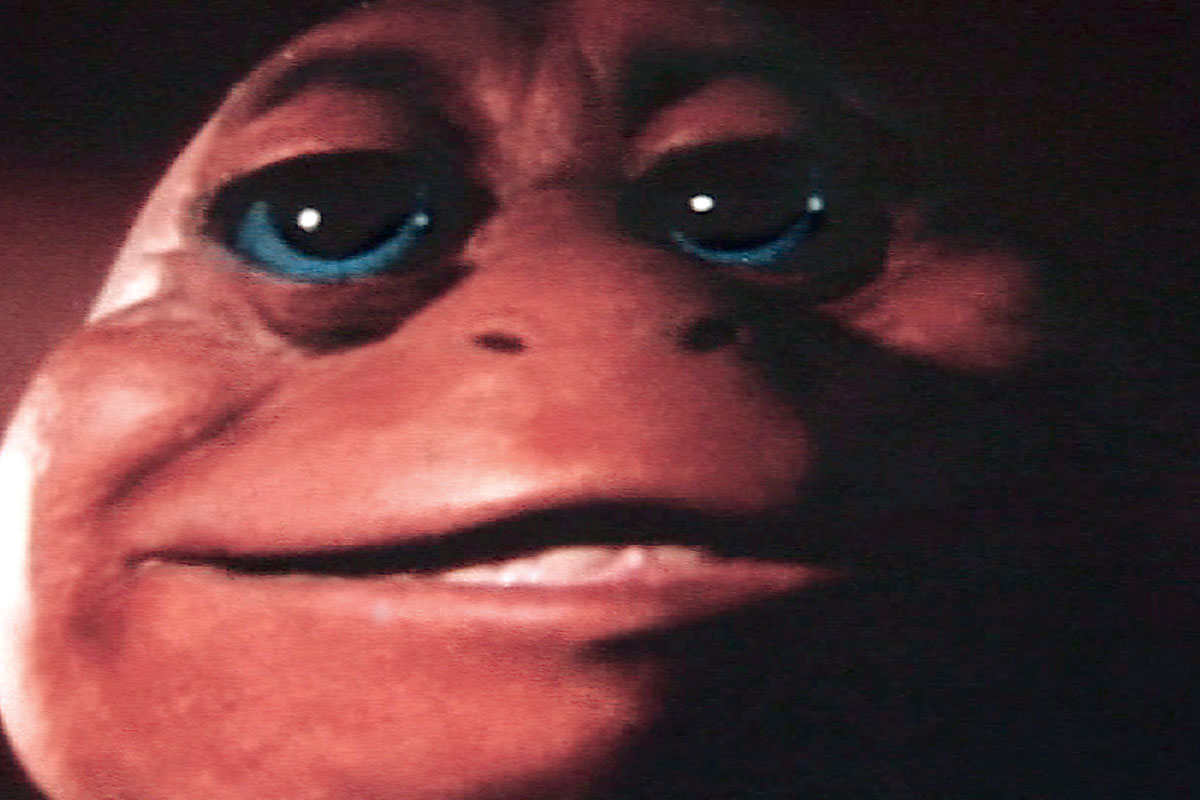

In the morning light, the prince discovers that something is moving under the blanket; a small lizard-like creature is looking at him with round, mocking eyes. Amazed, the prince stares back at the little monster. The creature leaps, lands on the chandelier, and immediately begins to feast on the metal candelabra. The monster clearly has an appetite for iron, which it chomps without the slightest resistance. It does not take long before the creature grows many times larger; no swords or lances can penetrate its armored body. Galgameth becomes the prince’s ally in the battle to uphold his father’s honor.

Galgameth is an American fantasy film from 1996 which passed quietly into the anonymous rows of VHS boxes in the children’s section of video stores. But for those who know the film’s genesis, it holds special significance. Galgameth is the last part of a monster genealogy that reflects political intrigues and raises questions about how the cute operates in the realms of art and power.

Galgameth can be traced to three earlier generations of monsters. The first is Godzilla—or Gojira, which is the original Japanese name—the mother of all film monsters. The first Gojira film from 1954 is a dark, melancholy elegy characterized by sophisticated visual language and sound design. There is nothing kitsch or ironic about it, even if the special effects can no longer impress a public that has grown up with digital imaging. The monster Gojira was a product of the atomic age; the film begins with scenes of a fishing boat that is hit by a devastating light, alluding directly to the American test in March of that year of a 1.5 megaton hydrogen bomb in the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. The Japanese tuna-fishing boat, Lucky Dragon No. 5, found itself in the vicinity of the test site and was enveloped by the radioactive fallout. The crew fell ill with radiation sickness and the incident triggered an international crisis. In Japan, fear of radioactivity once again took hold—the so-called “tuna fish horror.”

In the film’s story, Gojira emerges during the Jurassic period and survives at the bottom of the ocean only to have his habitat destroyed by the American test. After absorbing the radiation, the now homeless monster begins to wander. The Japanese fleet lays down depth charges and the military erects a high-voltage line to protect the coast, but nothing can stop Gojira. The scales on his back glow and a beam of radioactivity, transmitted from the monster’s jaw, makes buildings and houses melt.

The images from the film recalled the recent past for the Japanese nation. The smoking ruins of Tokyo the day after Gojira’s attack were a reminder of the devastating bombing of the city at the end of the war. The images of burned children being examined with Geiger counters at a hospital evoked the still-vivid memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The person responsible for designing the Gojira figure was Eiji Tsuburaya (1901–1970), the legendary special effects creator at the Toho Studios in Tokyo. Tsuburaya’s figures—such as Gamera (a jet-propelled giant turtle), Rodan (a flying dinosaur), Mothra (an enormous moth), Booska (a forerunner of the Teletubbies), and Ultraman (a humanoid alien in an attractive red and silver costume)—are still beloved by the Japanese public and have been reprised again and again in films, video games, comic books, TV series, and toys. But none of these figures rival Gojira—“Japan’s best-known international film star”—a national monument whose statue stands in Ginza in Tokyo. The Gojira series is one of the most enduring in all of film history, spanning over fifty years and twenty-nine movies.

Gojira’s success in Japan created a new genre, the kaiju film, which quickly spread to neighboring countries. In 1962, the South Korean filmmaker Kim Myeong-jae contributed to the genre with a film titled Pulgasari. The film itself has been lost, but two film posters found in recent years serve as proof of its existence. According to the Korean national film archive, the story, which takes place during the Koryo Dynasty (918–1392), is based on a Korean folk story: a martial arts master is murdered but reborn in the form of an iron-eating monster named Pulgasari who takes revenge on his murderers.

Like Galgameth, this film would also be a footnote in film catalogues were it not for a series of extraordinary events that unfolded at the end of the 1970s. South Korea was at that time a dictatorship under General Park Chung-hee. In schools, students learned that North Korea’s leader, Kim Il Sung, was a devil who literally had horns on his head. The censorship rules within the South Korean film industry were very strict, even though General Park himself was an enormous film fan. In 1961, he had fallen in love with a melodrama called Sangnoksu (“The Evergreen Tree”), a film that he came to regard as the cinematic national anthem of South Korea. The film was made by a young director, Shin Sang-ok, and the main role of the young self-sacrificing woman teacher at a village school was played by his wife Choi Eun-hee. In the 1950s, the married couple had established Shin Films following the Hollywood studio model. By the 1960s, the operation had grown to dominate the entire South Korean film industry, producing everything from period films, melodramas, horror films, and war films to musicals and “Wild East” movies, the so-called Manchurian Westerns.

Choi Eun-hee, known by film lovers as Madame Choi, was Korea’s greatest star. She had begun her career as a theater actress in productions of Shakespeare and Molière during the Japanese occupation (1910–1945), and was forced to perform for Japanese troops. Shortly after the Korean War broke out in 1950, she was kidnapped and brought to North Korea where she was compelled to appear in propaganda plays for the Communist troops. In 1953, she finally managed to escape and return to Seoul, where, instead of being welcomed, she was branded a traitor and brought to trial. The case was dismissed on one condition: that she entertain South Korean troops. Choi, considered to have the first “Western” face in Korean film (large eyes, strong eyebrows, and a pronounced nose), is said to be the most photographed figure in South Korean film history. She also broke many taboos: her 1958 on-screen kiss was the first in Korean history. In the 1960s, she took on an enormously diverse set of roles in Shin’s films: chaste widow, housewife, princess, and flirtatious prostitute in films centered on life around the American army bases. She was also the director of three films.

General Park was so eager to see Shin and Choi’s films that he demanded newly developed reels be brought directly to the presidential palace. The couple became constant guests of the dictator, who enjoyed playing cards with Shin, whose signature look at the time consisted of tinted pilot glasses and a black silk cravat with white polka dots. But the card games with the dictator came to an abrupt end in 1975 when Park got the idea that the director was conspiring against him and banned Shin from working in film. His studio was closed and his staff was dismissed. Around the same time, Shin and Choi divorced.

Shin died in April 2006. In July of the same year, we traveled to South Korea to meet with Choi Eun-hee. After long negotiations, she had agreed to meet us at the Marriott Hotel in central Seoul. We had prepared for our meeting with sessions at the national film archives, newly moved into laboratory-like premises in a building made of glass and polished stone. We had seen as many of her films as possible, but now we wanted to hear her version of the bizarre events that began in 1978.

The seventy-nine-year-old Choi arrived fully dressed in black. She had improbably smooth skin, full lips, tinted sunglasses, and a black onyx cross around her neck. Madame Choi told the story of her life methodically and chronologically. She became immersed in her own narrative, losing track of time; the hour we had been promised turned to five, extending to lunch at a bulgogi restaurant and soju drinking.

In 1978, Choi recalled, she was in Hong Kong on a business trip. On her way to a meeting, she was attacked; a sack was pulled over her head and she was taken to the harbor where she was placed aboard a small boat and injected with sedatives. After eight days, the boat docked at the North Korean harbor of Nampo. Waiting for her on the dock was a short man with a strange haircut. He greeted her with a smile: “Thank you for being here, Madame Choi. I am Kim Jong Il.”

Shortly after her arrival, Choi was dressed in traditional Korean clothes and photographed. Kim Jong Il proudly displayed the pictures to his father, Kim Il Sung, at the time the dictator of North Korea, who announced that Madame was still beautiful, especially dressed in hanbok.

Thereafter, Choi was invited to the Friday parties at Kim Jong Il’s personal palace, where she was expected to appear as if stepping out of one of her films. The parties would always include a film screening, followed by backgammon and mah-jong, punctuated by enormous glasses of cognac which had to be drunk standing on one foot. There was dancing to an all-female combo band, which played jazz and disco. In the small hours of the morning, Kim Jong Il would climb onstage and direct the band.

Kim Jong Il had an enormous archive of 35mm films, probably over 15,000, and was eager to discuss film with Choi. He could not emphasize enough the importance of film as a propagator of national identity and community. The archive was only accessible to the “royal family,” but Kim considered her part of the family. He seemed to forget that she was there against her will.

Outside of the weekly parties, it was an idle life for Choi in captivity. There was no certainty about her future and her days dragged on. Eating, she recalled, was “like consuming sand.” The years went by and she filled her days with gardening. She sculpted small clay cranes and placed them in the garden, their beaks pointing south.

Five years went by. For the last three, Choi had fallen out of favor and was no longer invited to the Friday parties at the palace. But then on 6 March 1983, an invitation arrived. It was a huge banquet with magnificent flower arrangements. Choi was seated as the guest of honor and Kim Jong Il was unusually excited. He made a speech in which he appointed her the mother of North Korea, the mother of Chosun. He talked about how Korea consists of one people, with a shared history and culture. And then the unbelievable happened: surrounded by dignitaries, Shin Sang-ok arrived. Dumbfounded, Choi stared at his emaciated face. Finally Kim Jong Il exclaimed, “Why are you just standing there? Come on, hug each other.”

It turned out that soon after Choi’s capture, Shin himself had been kidnapped. A failed attempt to escape his kidnappers landed him in a forced-labor camp, where for four years he survived by eating salt, grass, and bark. Now, Kim Jong Il wanted to crown them king and queen of the North Korean film industry—and declare them husband and wife. They had no choice but to accept. And so it was that Shin Films miraculously reemerged in North Korea, with Shin and Choi once again a married couple. They were given an enormous budget and a newly constructed film lot outside Pyongyang; they had access to as many extras as they needed.

Choi Eun-hee and Shin Sang-ok directed seven films in North Korea and assisted on ten others before they managed to escape. In 1986, Choi and Shin were invited to serve as jurors at the Vienna International Film Festival, but soon after their authorized arrival in Austria, they slipped away from their bodyguards and fled by taxi to the American Embassy.

The last film that Shin worked on in captivity, though he never managed to finish it, was called Pulgasari, like its South Korean precursor. The film was Kim Jong Il’s idea; the dictator had many opinions about cinema and was deeply involved in the country’s filmmaking industry. In an interview, Shin recalled that Kim Jong Il preferred action films, porn films, and horror films—his favorites were Friday the 13th, Rambo, and James Bond. According to Shin, Kim Jong Il believed that events portrayed on film were largely real: “I had to explain to him that most American films are fictitious.” But despite this confusion, Kim Jong Il perhaps intuited something deeper about the relationship between film and politics, a relationship illuminated by the neo-liberal concept of “soft power.” Soft power, a term coined by the American sociologist Joseph Nye, refers to a country’s ascendancy not through military or economic might but as a result of the enticements of its popular culture. Through soft power, popular culture disseminates latent political messages. Film humanizes people and places them in history; it mythologizes a country and its communities. Every shrewd politician with a feeling for soft power sees the potential of film to propagate narratives that tell how “our people” are human beings who suffer, love, and prevail.

Like the original version, the later Pulgasari, which helped establish the kaiju genre in North Korea, is based on a folk tale, but one now reworked according to revolutionary ideals. A blacksmith has been imprisoned for concealing his collection of metal tools, which are being forcibly seized across the land by a local warlord seeking raw materials to transform into weapons. Before he dies, the blacksmith makes a little figurine out of a grain of rice. His daughter, the heroine of the film, discovers it in his discarded clothes and takes it home as a memento.

In the evening, the heroine sits with her needlework; preoccupied by her sorrow, she happens to prick her finger. When a drop of blood falls on the rice figurine, a little blue halo of light appears above it without her noticing. When the figurine wakes up the next morning, it immediately grabs one of the needles in her sewing kit, puts it in its mouth, and bites it in two. Gorging itself until there are no more needles, it then leaps into the girl’s arms to nibble at the needle she holds between her fingers.

Pulgasari quickly bulks up on this iron diet, and joins the villagers in their uprising against the feudal overlord, which culminates in an attack on the imperial palace. But the monster is ultimately too demanding, as its enormous appetite for iron makes it increasingly difficult to feed. The heroine finally martyrs herself in order to destroy Pulgasari’s rapacity: just as her blood fosters its initial hunger for iron, so it ends it. That Gojira is the forerunner to Pulgasari is exemplified by the fact that Choi and Shin hired Toho Studios, the special effects team from Tokyo, to work on the film. It was Kempachiro Satsuma, a longtime portrayer of Gojira, who was given the task of bringing the Pulgasari rubber costume to life.

All North Korean films are made for domestic consumption, and so every film has to be seen as a message to the nation’s own inhabitants. One might interpret Pulgasari as a critique of the dictator’s power over the people, the emperor symbolizing the despot Kim Il Sung who lives luxuriously while his people suffer hardships. But such a critical perspective is, of course, officially impossible in North Korea: the oppressors must be capitalists from South Korea, Japan, or the US. It is against them that weapons must be directed. The weapons in Pulgasari are created from within, from soil, rice, and blood. The food—iron—is uranium, enriched in the blacksmith’s forge. The weapon is transformed and refined into an increasingly diabolical force. In the end, it is only the spirit of the people that can disarm the weapon. As it happens, the North Korean nuclear weapons program had secretly commenced by that time, and the national mentality needed to be prepared for this step.

In addition to the nuclear weapons motif, something else connects Gojira and Pulgasari: ambiguity in the face of horror. In both films, the monsters are expected to be terrifying. They come bearing destruction, they run amok, and they have the power to wipe out the entire human race. But at the same time, these monsters have mitigating qualities. In Pulgasari, this equivocation becomes clear in certain scenes that show the monster as a playful, even cute character. A similar ambivalence was only very weakly suggested in the original Gojira film, but the later films show a more conciliatory attitude toward the monster. In the 1968 film Kaiju Soushingeki (“Destroy All Monsters”), Gojira is even represented as the overindulgent parent of the cuddly Minilla.

In other spheres of Japanese popular culture, this movement back and forth between the beastly and the cuddly has always been very clear. During the last few decades, the influence of the cute has expanded enormously at the expense of the terrifying. The concept of kawaii has become pedestrian in popular culture, and manifests itself everywhere in a city such as Tokyo: in advertising, apparel, costumes, trinkets, posters, cars, and even the architecture. Kawaii has become the most important source of soft power.

That Shin, who received asylum in the United States along with Choi, should ultimately go on to make Galgameth, a new, ultra-cute version of Pulgasari, parallels this trajectory of power camouflaging itself as cuteness. China is rapidly adopting a similar course: street signs prohibiting certain behavior now feature pictures of large-eyed, doll-like policemen who smile as they raise a warning finger. There is even a name for this development in China: “panda politics.”

Under the pseudonym Simon Sheen, Shin took Kim Jong Il’s idea to Hollywood, or rather, to a castle in Romania, where Galgameth was filmed. Many scenes—for example, the one in which the monster first appears—are borrowed directly from Pulgasari. From a psychological perspective, it is incomprehensible that the director, after years of working in a labor camp and being forced to make films in North Korea, would choose to do a remake of his captor’s artistic vision after finally escaping to the US. Was it a case of traumatic repetition-compulsion? Exorcism? Or simply greed? When we contacted the Gojira actor Kempachiro Satsuma’s agent in Tokyo, we learned that Shin had made inquiries about whether Satsuma would consider acting the role of Galgameth (Satsuma declined). Perhaps Shin had a vision: the same actor in three different monster costumes, representing three different political systems.

By September 2008, when we visited the studio complex outside Pyongyang where Pulgasari was filmed twenty-three years earlier, the huge buildings erected for Shin and Choi stand as isolated monuments. The golden age of North Korean film is over. We can now walk through the muddy streets where film crews erected a vision of Seoul under Japanese occupation. Among the other sets we find a decadent bar district in Tokyo; naïve backdrops for narratives about immoral living in contemporary Seoul; buildings from the Chosun era; and even a Bavarian village—a convincing illusion at a distance, though closer inspection reveals that the houses are made of military-grade cement. Ordinary North Korean citizens’ ideas about the world outside the country have shaped these sets. Our guide tells us that Kim Jong Il comes here from time to time to provide “on-the-spot guidance.”

It was different in Choi and Shin’s era. Madame Choi tells us that Kim Jong Il had full faith in their filmmaking, and that while he was entirely engaged in it, he never imposed himself. We are astonished by her forgiving attitude toward the dictator; she even seems to have a slightly guilty conscience overt the fact that they managed to escape from captivity, leaving the North Korean propaganda factory to its fate.

Magnus Bärtås, an artist and writer, is professor of fine art at Konstfack in Stockholm. Together with Fredrik Ekman, he has published two books of essays, Orienterarsjukan och andra berättelser and Innanför cirkeln (Bokförlaget DN, 2001 and 2005, respectively). He has recently participated in group shows at the Zendai Museum of Modern Art in Shanghai, the Museum on the Seam in Jerusalem, the Miroslav Kraljevic Gallery in Zagreb, and the Seoul Photo Fair.

Fredrik Ekman is a writer, librettist, and editor. Together with Magnus Bärtås, he has published two books of essays, Orienterarsjukan och andra berättelser and Innanför cirkeln (Bokförlaget DN, 2001 and 2005, respectively). With composer Erik Mikael Karlsson, he has produced a number of electro-acoustic pieces and musical radio dramas, notably Night of Enchantment and Die Hoffmann-maschine.