Artist Project / The Dreamer, or, the Adventures of a Luftmensch

Albert Grass and the Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society

Zoe Beloff

When the Coney Island Museum invited me to create an exhibition to celebrate the centennial of Sigmund Freud’s visit to Coney Island and its Dreamland amusement park in 1909, I readily agreed. But rather than simply illustrate his afternoon at the seaside, I wanted to explore the great psychoanalyst’s legacy via the dreams and desires of those who lived, worked, and played in Coney Island in the decades that followed. The archive of the Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society provided the perfect framework for this investigation.

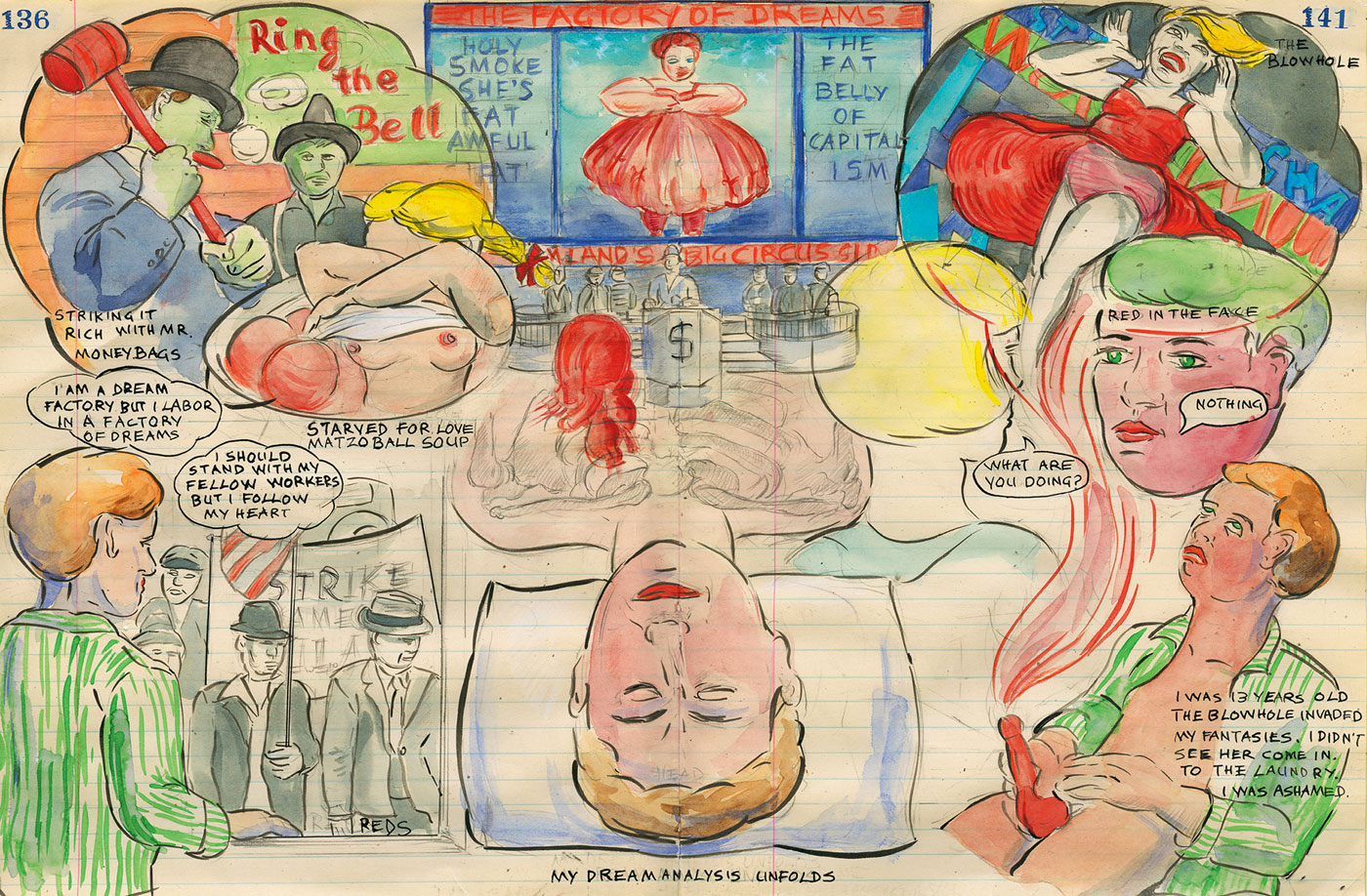

The Society was founded in 1926 by Albert Grass, a designer of amusements at Coney Island.[1] Precisely how he discovered Freud’s writing remains unclear, but when he returned from World War I, where he was stationed in France as a member of the Signal Corps, he was a passionate convert to the new discipline of psychoanalysis and was determined to share his enthusiasm with his friends. The members of his fledgling society, most of them Jews and Italians from the surrounding neighborhoods, grasped its utopian potential: while socialism might free workers from the tyranny of class, psychoanalysis would also liberate their psyches from the cultural and sexual mores of the time. They took difficult, abstract, European concepts and with a hands-on American spirit—and a sense of playfulness born out of their proximity to the “people’s playground”—applied them to their own lives. Grass, for example, initiated an annual “dream film” competition, inviting members to recreate their dreams on film and analyze them.[2] And in the late 1920s, he worked tirelessly to rebuild Dreamland, which had been destroyed by fire in 1911, as a great Freudian theme park. He produced numerous plans and sketches, but unfortunately he was not able to raise the necessary capital to realize his vision.

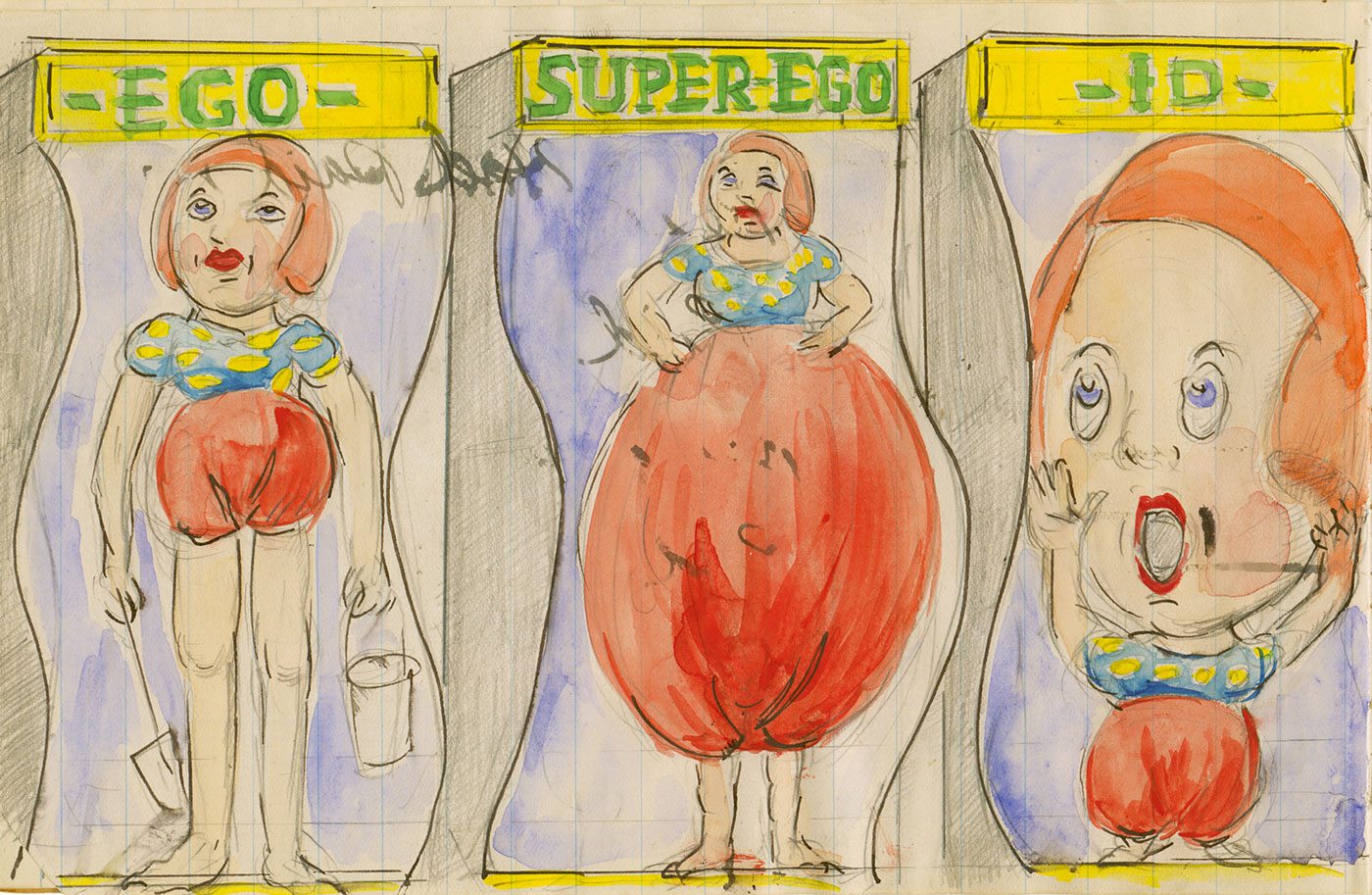

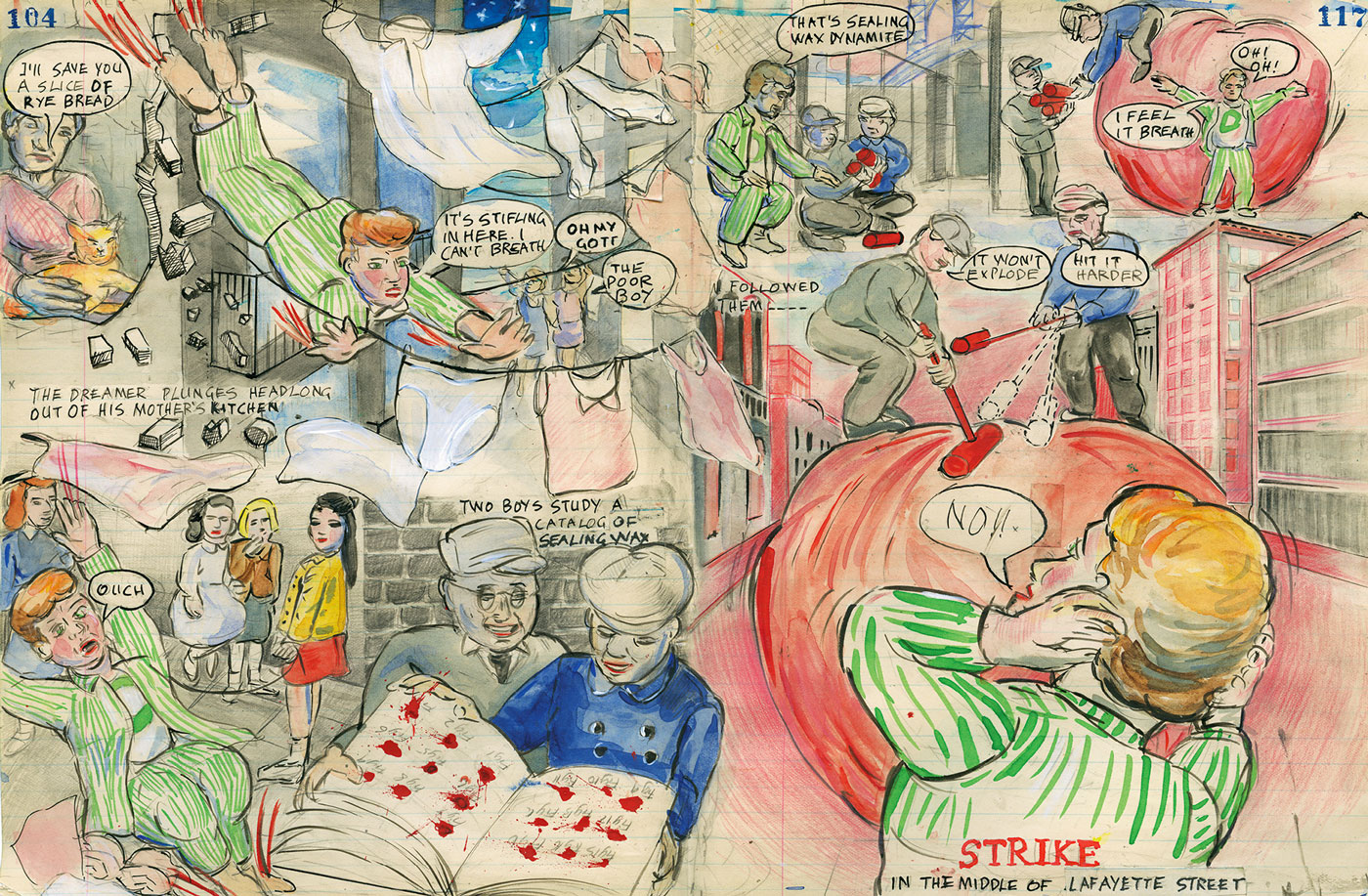

My book The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and Its Circle documents the work of the society but does not address what Grass did after it became clear that Depression-era New York was not ready for an amusement park that featured a fifty-foot-high “Libido” pavilion in the form of a half-naked prepubescent girl. To date, my research into Grass’s next venture, “The Dreamer,” is in its early stages.[3] It appears to have been a dream journal, started in the late 1930s, which he articulated in the language of comic books. In each episode, the hero is plunged into a strange and troubling dream and then, upon awakening, attempts to analyze it using Freud’s method of free association. I imagine Grass created the journal to share with the fellow members of the society. In many ways, the idiom of the comic book as a means to explore the unconscious makes perfect sense. Comic books, which were rapidly gaining in popularity, depicted fantastic and bizarre worlds in which the demons of the id regularly battled it out.

Comic books were also a singularly Jewish medium. In an era where discrimination against Jews meant they were unable to get jobs as commercial artists for magazines and advertising, comics were the one place they could work since many were Jewish-owned. Most of the great comic book creators were indeed Jewish, such as Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, whose Superman inspired a legion of superheroes that continue to this day. In fact, it has been argued that the idea of the masked superhero who had two identities resonated particularly with Jews, who themselves had to create bland Waspish identities if they wanted to get ahead.

But Albert Grass was not one to bow to commercial and ideological pressures: his character can proudly claim to be the first “out” Jew in comics. Although he owes much to pajama-clad little Nemo from the famous strip by Winsor McCay, “The Dreamer” is also a portrait of the artist as a young schlemiel who never manages to get dressed in the morning and is forever at the mercy of his nagging mother. Only occasionally, stripping off his pajama shirt to reveal a big D on his undershirt, does he come anywhere close to the muscle-bound superheroes drawn by Grass’s contemporaries. But as he remembers in an early episode, the letter D also stands for dunce, his teachers’ favorite appellation for him as a child. It is clear that the Dreamer embodies the classic figure of the luftmensch, which in Yiddish literally means “air man” (since he has the superhero’s ability to fly) but is also used colloquially to describe an impractical dreamer incapable of earning a living.

- Like many immigrants whose families passed through Ellis Island, there is some confusion over his name. I have seen it rendered both as “Glass” and “Grassman.”

- Grass learned cinematography in the US Army’s Signal Corps. Many members of the Society also belonged to the Amateur Cine League, another society founded in 1926 by a Brooklynite named Hiram Percy Maxim.

- This character should not be confused with Will Eisner’s autobiographical character, the Dreamer, from his comic book of the same name published in 1986. Eisner, a great pioneer of the comic book form and the originator of the graphic novel, was enormously productive, and his Dreamer is highly competent and rooted in the real world.

Zoe Beloff is a New York–based artist. Her exhibition “Dreamland: The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and its Circle 1926–1972” is on view at the Coney Island Museum through 21 March 2010. Her installation Somnambulists is touring England as part of “Magic Show,” curated by Jonathan Allen and Sally O’Reilly, through December 2010. For more information, see zoebeloff.com.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.