Hot on the Trail

The culinary genius of Alexis Soyer

Thomas A. P. Van Leeuwen

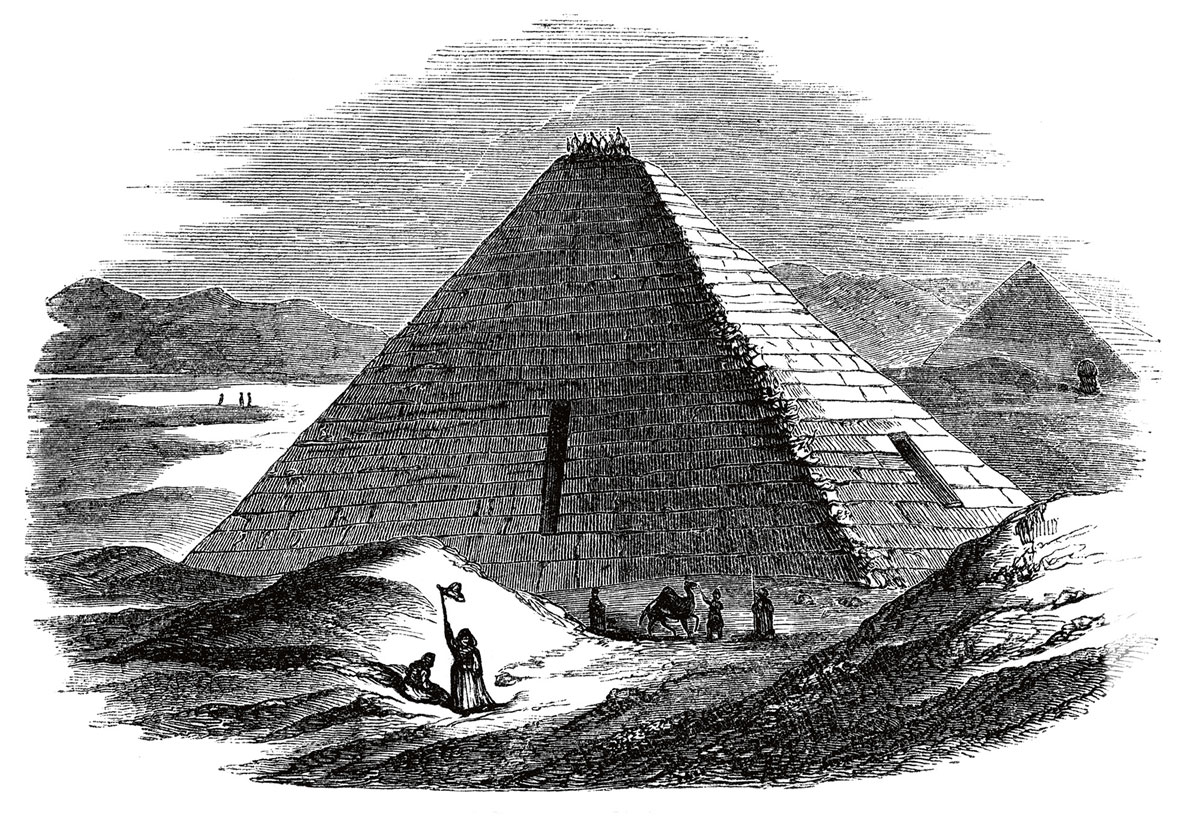

“You reproach me for not sending you one earlier,” Alexis Soyer wrote in the introduction to the 1851 edition of his book of recipes The Modern Housewife. “That which I intended for you has been taken by the Marquis of N. [Normanby] and party to Egypt, with the view of having a dinner cooked on the top of the Pyramids.”[1]The Marquis of Normanby was an eccentric, somewhat Jules Vernesque aristocrat to whom Soyer apparently had lent his latest culinary invention: a proto-camping gas cooker called the Magic Stove.

Undoubtedly, Normanby’s choice of location was audacious and original. Picnicking, that unique Victorian jumble of high-class formality and bucolic joviality, relied in large part on spectacular locations. The fun of the picnic was not so much about eating and drinking in the outdoors, but about moving the whole formal dining experience—complete with cutlery, wine cellar, servants, and appropriate attire—to the countryside. An abrupt contrast between formal interior and informal exterior, between civilization and nature, was essential; the more contrast, the more fun. In that respect, the pyramids could not have been better chosen. Another obvious contrast was that a well-appointed picnic basket typically held only cold food: smoked salmon, cold cuts, biscuits, fruits, cakes. Cooking on the spot was not (yet) in fashion. Soyer’s Magic Stove was to change all that. Exactly what made the picnic on the pyramid so utterly exciting was that the meal was cooked and served hot. Not only the dining room but also the kitchen was transported to this improbable and truly inaccessible location. In the history of the picnic, the experience of dining atop a pyramid could merely be regarded as the gradual, if daring, evolution of an already established theme, whereas the portable cooker heralded a total revolution.

Alexis Soyer (1810–1858) was indeed a true revolutionary. He arrived in London in 1841, blown over from France by the July Revolution, and took a position as the chef de cuisine of the Reform Club on Pall Mall newly built by architect Charles Barry, who at the time was also working on the nearby Houses of Parliament.[2] The new chef caused a veritable storm in Britain’s arch-traditional culinary scene. Soyer excelled in the organization and mechanization of his trade. His custom-built kitchen at the Reform Club was a marvel of ergonomics and cooking technology. A 3-horsepower steam engine pumped up water, heated the bains-marie, and drove the spits, dumb waiters, and ventilator fans. Right after the invention of coal-extracted gas, Soyer directed gas mains into his kitchen to heat the cooking pots (gas had been used for lighting since the early 1810s, but not for cooking). For club members alone, he cooked five meals a day, totaling hundreds, even thousands, of breakfasts, coffees, lunches, teas, dinners, and after-theater suppers.

The introduction of the gas stove and the other futuristic novelties of Soyer’s kitchen drew large crowds to the Reform Club. The chef even conducted his own tours; one year, more than fifteen thousand visitors attended.[3] Large numbers indeed fascinated him. The London Universal Exposition of 1851 even challenged him to mount an operation called “Soyer’s Universal Symposium of All Nations,” a giant thematic food park adjacent to the fair grounds, where specially prepared meals from all corners of the world were to be served to five thousand guests on a daily basis.

Soyer marketed household versions of his own designs as spin-offs from his professional operations: a patented tendon separator; the “Alarum or Cooking Clock”; steam-heated fish-pans; patented teapots; a range of potted, original Soyer sauces; cookbooks; and the first domestic gas stove—the “Phidomageireion or Modern Gas Cooking Apparatus.” (This unwieldy name translates as “thrifty kitchen;” Soyer was rather fond of monikers derived from classical Greek.)

Soyer’s penchant for Greek names aside, the Magic Stove—the first version of which he registered with the patent office in 1849—was more Omar Khayyam than Aristotle, gesturing toward a world of leisurely comfort as well as heavenly flavors. The small, portable burner was designed to run on pressurized fuel and to have sufficient heating power to cook a meal in a couple of minutes.[4] The Magic Stove’s first appearances in the great outdoors reflected the grandiosity of its gentlemanly origins. Normanby’s request for a pyramidal trial was not the most outlandish: “Mad” Lieutenant Gale, a daredevil hot-air balloonist, wanted to take the Magic Stove on board, but died too soon in a botched ascent. Explorers took the stove with them on their expeditions. In 1850, the Admiralty ordered some Magic Stoves for Captain Horatio Austin’s expedition to the Arctic in search of Sir John Franklin, prefiguring Amundsen’s use of the Primus stove on his journey to the North Pole.

Soyer wanted his stove to be a “must-have,” an irresistible gadget that would look great “in the parlour of the wealthy, the office of the merchant, the studio of the artist, or the attic of the humble.”[5] (Its successor, the better-known Primus developed by the Swedish inventor F. W. Linquist, did not come on the market until the end of the nineteenth century.) Newspapers praised it and found it “so certain in its operations that a gentleman may cook his steak or chop on his study table, or a lady may have it among her crochet or other work.” Outdoor use was advocated as well for “the sportsman on the moors, or the angler by the side of the mountain stream.” The stove was small enough, it was said, that it could be carried in one’s hat.[6]

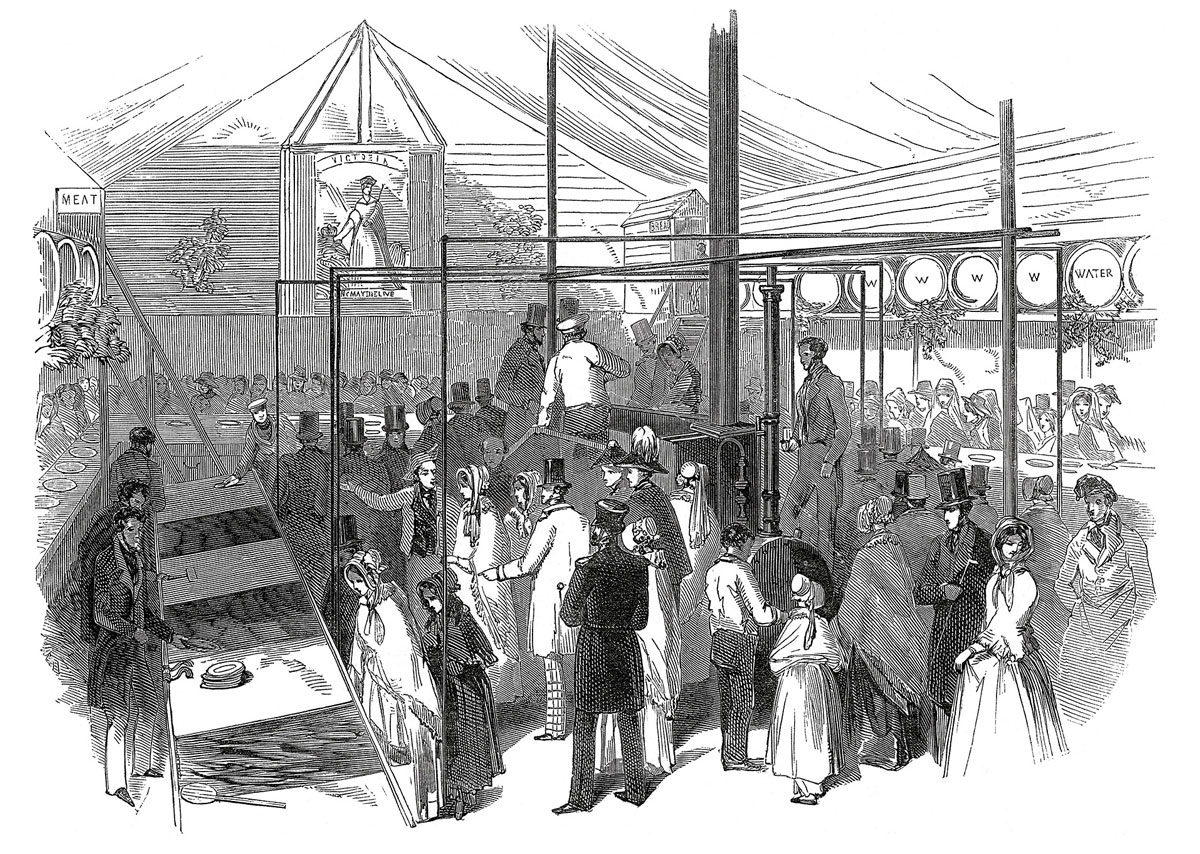

In 1847, at the height of the Irish Famine, Soyer was invited by the Lord Lieutenant to devise a new model soup kitchen for the starving, one that improved on the existing models by bringing Soyer’s efficient, scientific methodology to what had been rather haphazardly run enterprises. He managed in very short time to sketch the kitchen, and have it designed by the leading engineering firm of Bramah, Prestage & Ball; it was swiftly mass-produced and shipped to the suffering areas.[7] These kitchens, established in South Dublin, eventually served more than one million portions.

Later that year, Soyer also set up soup kitchens in the ultra-poor French Protestant neighborhood of Spitalfields in East London. He was so horrified by the living conditions he witnessed there that he wrote letters to various papers, including the Times of London: “We found, in many of the houses, five or six in a small room, entirely deprived of the common necessaries of life—no food, no fire, and hardly any garment to cover their persons, and that during the late severe frost.” He found a mother and her children starving, having “not tasted a bit of food for twenty-four hours, the last of which consisted of apples partly decayed, and bits of bread given to her husband.”[8] No contrast could be more heartbreaking than this picture of total deprivation and the boundless opulence of the tables of Pall Mall. Soyer took immediate action. “I immediately proposed that my Subscription Kitchen for the Poor, which was being made at Messrs. Bramah and Prestage’s factory, should be erected, without any loss of time, in the most populous district of Spitalfields.” In about a week, the soup kitchen had been set up, and was able to produce an excellent “meat-soup [bouillon] in less than one hour and a half, and this at very moderate expense—the quickness and saving of which are partly owing to the contrivance of my new steam-apparatus, and which food was distributed, in less than twenty minutes, to about THREE HUNDRED AND FIFTY CHILDREN.”[9] Soyer not only offered his services for free, he also donated the generous sum of fifty pounds toward the kitchen’s manufacturing costs.

To the irritation of both London housewives and Irish famine victims, Soyer suggested that backwardness and ignorance had contributed to their lamentable situation just as much as the cruel actions of their landlords. He argued that the problem might not just be the lack of food, but the lack of healthy food. Vegetables were notoriously absent and if there were any, they had been treated in such a way that they had lost all their useful nutrients. The simple land folk had to be educated in exploring new sources of nourishment.[10] He tried to make the victims aware of their lack of resourcefulness, a shortcoming which he tried to remedy with his very best advice as well as the production of cheap cookbooks such as Soyer’s Charitable Cookery, or, the Poor Man’s Regenerator, Addressed to the World in General, but to Ireland in Particular (1848) and, six years later, A Shilling Cookery for the People.[11] Soyer followed in the footsteps of his French predecessor François Cointeraux, better known for his ultra-economic building and fireproofing technique of pisé than as an advocate of rustic cooking. In his hilarious La cuisine renversée ou le nouveau ménage of 1792, Cointeraux enthusiastically promoted the cultivation and consummation of the potato, together with a set of highly sophisticated ways to arrange the kitchen, select a proper stove, and maintain a kitchen chimney.[12] For the potato-eating Irish, on the other hand, Soyer suggested a radically different diet of fish and mollusks, to be harvested in overwhelming plenitude from the island’s “streams and the surrounding seas.”[13]

Florence Nightingale was the first to act: she recruited a taskforce of thirty-eight nurses and set out for the barracks in Scutari, on the Turkish coast. What she found there was of s h excruciating horror that it made her write down the historic phrase that it was “a calamity unparalleled in the history of calamity.” The public indignation that followed was so massive that the responsible prime minister and his war secretary were sacked and succeeded by the relatively fast-acting team of Lord Palmerston and his new secretary of war, Lord Panmure. Panmure sent out a Sanitary Commission to investigate the situation, and when they returned with even more horrifying reports in November 1854, Alexis Soyer (by now an experienced chef sans frontières, first-aid cook, and culinary relief soldier) immediately offered his services.[15] Through his well-established social network, Soyer approached Panmure with an offer to help with what he could do best: setting up field kitchens and designing recipes that could restore life to the dying soldiers.

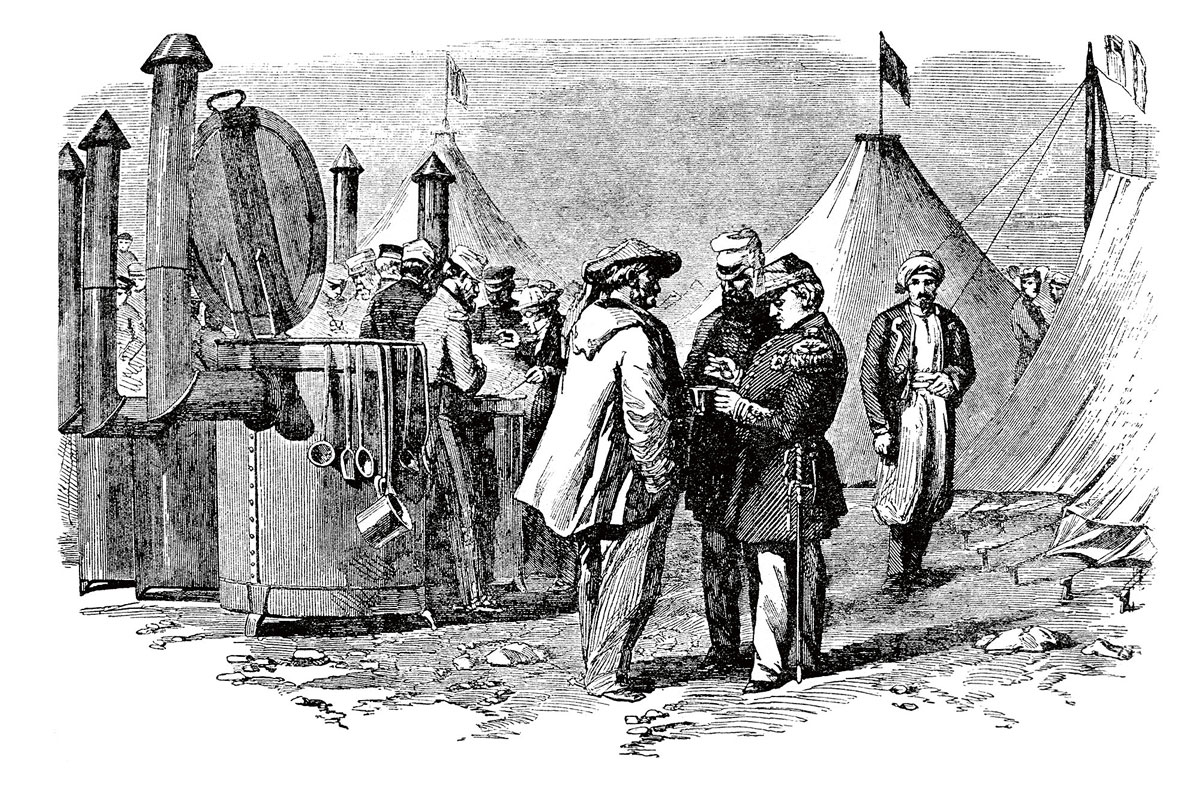

In keeping with his love for efficiency and his disgust of improvisation, Soyer did not embark until he had prepared the machinery needed to succeed in the wilderness of Northern Turkey (where the troops were quartered) and in Crimea. Though his first assignment was to repurpose the soup kitchen that had been deployed during the Irish Famine of 1847 as the new kitchen for the Scutari barracks,[16] his main goal was to use his new field stove to set up kitchens for soldiers at the front. “In a very short time I hit upon an idea [for the field stove] which I thought could be easily carried out, and would answer perfectly. Losing no time, I jumped into a cab and immediately drove to the eminent gas engineers and stove makers, Messrs. Smith and Phillips, of Snow-hill. On submitting my plan to those scientific gentlemen, they pronounced it practicable, and promised me a model, one inch to the foot, to be ready in a day or two.”[17] Soyer’s easily transportable stove, which could be made in a variety of sizes, was an enclosed unit where the limited combustible material (in addition to wood, it could utilize fuel ranging from dried dung to coal, important since the landscape was largely without trees) was concentrated and directed to a single heating surface: the cooking pot above. With a minimum of input, an unusually large output was secured. With Panmure’s approval, manufacturing began on ten large and four hundred small field stoves, to be used in Scutari’s hospital kitchens and at the front in Crimea, respectively.

Soyer took the model field stove with him to Scutari in March 1855, and after reorganizing the kitchens there (without the benefit of the large stoves, which had been delayed in transit) set out for the Crimean battlefield in May; once there, he immediately met with the British commander-in-chief, Lord Raglan, who agreed that when the shipment of field stoves arrived, Soyer could himself introduce them into the regiments.[18] Several hundred were delivered and instantly made operational in the summer of 1855. Soyer stayed in Crimea long enough to witness the decisive battle of Sebastopol in September 1855, and was in Constantinople when the war was officially concluded with the Peace of Paris in February 1856. His lengthy stay was in part the result of a nearly lethal infectious disease—the same that almost killed Nightingale—which forced him to spend the final months of 1856 in various hospitals and hotels until he was fit enough to travel back to western Europe. He finally arrived home in London in May 1857.

It is ironic that this gastronomic genius, who came to fame as chef de cuisine of the Reform Club, ended his career as a cooking instructor with the army. After his return to London, his life was more or less spent; he suffered from the Crimean Fever and had lost much of his personal fortune. Staying within the routine of the Crimean campaign, he finished his romanticized report on the war and had it published in 1857 as A Culinary Campaign (subtitled Being Historical Reminiscences of the Late War, with the Plain Art of Cookery for Military and Civil Institutions, the Army, Navy, Public, Etc., Etc.,); he went around lecturing about his kitchens, including his design for a totally mobile new army kitchen that could “cook whilst on the march, if on an even road.”[19] In a lecture delivered to a packed house at the United Services Institute, Soyer continued to advocate for his military culinary reforms, and “promoted his ‘cooking carriage’ to get hot food to soldiers in the trenches at night.”[20] His final act was to install new kitchens at the Guards Depot at Wellington Barracks, incorporating the latest gas ovens. A week after the inauguration ceremony, he was taken ill again and never recovered, dying on 5 August 1858 at the age of forty-eight.[21]

The field stove had been amply tested in and around the combat zone, and had passed the severest of trials. In the end, it had proven itself so well that it was adopted and used as standard British army equipment right up to the modern era. In her 1938 book, Helen Morris, Soyer’s first modern biographer, showed a photograph of a 1930 field stove and reported that it continued to be used by the entire army.[22] A post–World War II original, stamped “Wolverhampton 1953,” is still in the collection of the Wellington Barracks in Birdcage Walk, London. And according to military historian John Barham, “the Soyer stove remained the staple equipment for battalion cooking … until well into the 1980s.”[23]

Even in Turkey, the Soyer field stove never really went away. In 1989, I purchased a charming “camping barbecue set” in Bursa, Turkey. A small tin drum sprayed industrial brown, it sits on baroquely shaped feet and sports a small stovepipe topped with a perky little cap. The drum, like the field stove, has a lower compartment into which fuel is fed, and there is a cooking tray above it, on which meat could be grilled or a pan heated. The frying pan doubles as a lid. Only much later, long after I got acquainted with Soyer and his field stove, it struck me that this “Piknik Izgaralari” (picnic barbecue set) was not a regrettable, made-in-China knockoff. It is an unconsciously patriotic reminiscence of the Allied victory over the Russians in the Crimean War, and of the man who brought relief to a disease-stricken part of the Ottoman Empire with the help of an oversized “Piknik Izgaralari.”

- Alexis Soyer, The Modern Housewife, or Ménagère, Comprising Nearly One Thousand Receipts for the Economic and Judicious Preparation of Every Meal of the Day and Those for the Nursery and the Sick Room Etc. (London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., 1851), p. vi.

- See my article “The Magic Stove: Soyer, Barry and the Reform Club, Part 1,” in Hunch: The Berlage Institute Report on Architecture, Urbanism, and Landscape, no. 12 (2009) and “Part 2,” in Hunch, no. 13 (2009). The author wishes to thank Simon Blundell and Roy Tassi of the Reform Club for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

- Ruth Cowen, Relish: The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer, Victorian Celebrity Chef (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2006), pp. 48–49. Interest in Soyer has increased considerably in the last ten or so years. For a long time, the only biography in print was Helen Morris, Portrait of a Chef: The Life of Alexis Soyer, Sometime Chef of the Reform Club (New York and Cambridge: MacMillan & Cambridge University Press, 1938). For Soyer’s Crimean campaign, see the introductions by Michael Barthorp and Elizabeth Ray to Alexis Soyer, A Culinary Campaign (Brighton: Southover Press, 1995).

- The Magic Stove was magic in the sense that it was diminutive, especially for a time in which everything was big, heavy, and over-engineered, but produced an improbably powerful effect. Somewhat illogically, its disposition was sideways: a central support was laterally connected by a pipe to a lamp-shaped spirit burner. “When the spirit lamp was lit, the vapor it produced was forced through the blowpipe into the stove unit, where it connected with a reservoir of methylated spirit to produce a flame of ‘intense heat, double that of a charcoal fire.’” See Cowen, Relish, p. 162.

- Morris, Portrait of a Chef, p. 60.

- Ibid., p. 61.

- T. W. Moody and F. X. Martin, The Course of Irish History (Cork: The Mercier Press, 1967), p. 270. “To begin with, an act was passed providing for the establishment of kitchens and the free distribution of soup. The most dramatic result of the measure was the expedition of Alexis Soyer, the famous chef of the London Reform Club, to set up his model kitchen where soup could be made according to the same recipe as that which he had devised for the London poor.”

- Ruth Brandon, The People’s Chef: A Life in Seven Courses (London: Wiley, 2004), p. 153.

- Alexis Soyer, Soyer’s Charitable Cookery, or, the Poor Man’s Regenerator, Addressed to the World in General, but to Ireland in Particular, available in Soyer, Modern Housewife, p. 484.

- See Soyer, Soyer’s Charitable Cookery.

- Alexis Soyer, A Shilling Cookery for the People Embracing an Entirely New System of Plain Cookery and Domestic Economy (London: G. Routledge & Co., 1860).

- François Cointeraux, La cuisine renversée ou le nouveau ménage, par la famille du professeur d’architecture rurale (Lyon: Ballanche & Barret, 1792).

- Nothing could have been more politically incorrect than Soyer’s remark that although the potato crops might have failed, the Irish waters still abounded with things perfectly edible: “… to impress upon your minds that the country produces plenty of vegetable and animal substances, and the waters washing your magnificent shores teem with life, which the all-wise Providence has given as food to man, and that they only require to be properly employed to supply the wants of every one with good, nourishing, and palatable food.” See Soyer, Soyer’s Charitable Cookery, p. 482.

- For this aspect of the war, see Andrew Lambert & Stephen Badsey, The Crimean War (Dover, NH: A. Sutton, 1994).

- Why Soyer was so instantly convinced that he had to leave the safe comfort of London to challenge fate and solicit his death in the war zone is psychological history. Brandon, People’s Chef, p. 228: “Soyer’s departure was the logical continuation of a career that, ever since 1847, had taken an unusually radical direction. Most upper servants like Ude [Soyer’s forerunner as a French chef de cuisine on British soil] drew a kind of reflected prestige from the exalted households in which they worked. … But Soyer had always found service demeaning, however much he might enjoy the culinary and social opportunities it afforded. Paradoxically, given that his attitude to the rich and powerful was little short of fawning, his social views ... were singularly democratic.”

- Soyer, A Shilling Cookery, p. 183.

- Alexis Soyer, A Culinary Campaign (London: G. Routledge & Co., 1857), p. 39.

- See Cowen, Relish, p. 289.

- Soyer, A Shilling Cookery, p. 184. From “Soyer’s Kitchen for the Army,” an appendix later added to original 1854 edition.

- John Barnham, “Recipes from Disaster—Conclusion,” available at goo.gl/tMtMY. Accessed on 30 July 2012.

- “The achievements of Alexis Soyer in the development of British Army catering were hugely significant. Perhaps his most important success, and also his first priority, was that he converted senior military thinking to the belief that the British soldier would stay far healthier and fight better if he was well fed. Soyer understood the character of the average squaddie enough to know that to guarantee this, his rations needed both to be palatable and to be prepared for him. The methods required to achieve this—the establishment and training of specialist cooks, and the provision of practical, efficient, and soldier-proof cooking equipment—followed on from there. To that extent he is arguably the founder of modern military catering; the fact that an Army Catering Corps was not founded as such until 1941 is unimportant in this context—ACC personnel were always attached to the units of Arms and other Services, and fully integrated into the activities of these units, as Soyer’s cooks were.” Barham, “Recipes from Disaster.” For the Wellington Barracks kitchen, see Cowen, Relish, p. 316.

- “… and it is still, as General MacMunn wrote in 1935, ‘among the most essential articles of camp equipment.’” Morris, Portrait of a Chef, p. 131.

- Barham, “Recipes from Disaster.”

Thomas A. P. Van Leeuwen was professor of architectural history, cultural history, and art criticism at Leyden University for many years. He presently teaches at the Berlage Institute, Rotterdam. His books include The Skyward Trend of Thought: Metaphysics of the American Skyscraper (MIT Press, 1988) and The Springboard in the Pond: An Intimate History of the Swimming Pool (MIT Press, 1998). These studies are part of a tetralogy with each volume centered on the relationship between architecture and one of the classical elements. In preparation are Columns of Fire: The Un-doing of Architecture and The Thinking Foot: A Pedestrian View of Architecture.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.