Kiosk / Spring 2015

In the nooks and crannies

Cabinet

Some awards are harder to get than others. Take the Dickin Medal, for instance, which honors animals’ service during war (see George Pendle’s article in this issue). Dozens of dogs and pigeons, and a handful of horses, have won the award but only one cat—the mighty Simon—has been recognized in the seventy-odd years that the medal has been given. This makes a certain sense, given that dogs, pigeons, and horses can be trained to carry out duties crucial to the war effort. But this downplays the vital role of morale, which is where the cat really comes into its own. During the darkest days of war, the cat offers comfort by sitting in soldiers’ laps, purring in the right way, and turning over to have its belly rubbed vigorously. This may seem like a small service, one that does not merit official recognition, but it is worth noting that the cat alone behaves as it does entirely of its own volition. Knowing that an animal has been trained to perform a certain duty effectively turns that animal into another soldier, but the cat, in its utter indifference to any form of instruction, is the only one that can raise morale, precisely because the soldier knows that the cat is keeping him company because that’s what it really wants to do. Perhaps the bestowers of the Dickin Medal should consider this when making their selections in the future, though it is of course highly unlikely that any cat would deign to attend a ceremony that imagines humans to be in a position to be handing out medals.

• • •

Author Bill Bryson, on the other hand, has attended numerous prize ceremonies. His bestselling A Short History of Nearly Everything, which sold millions of copies worldwide, won the 2004 Royal Society Aventis Prize and the European Union’s 2005 Descartes Prize. In researching the Chicxulub meteorite (see Maria Golia’s text in this issue), we came across some data in Bryson’s book that made our eyes pop. Did you know, for instance, that the shockwave produced by such an object striking Earth would travel at “nearly the speed of light”? We hope not, because this figure is massively wrong. In fact, if an error this large were to hit Earth, there would be no crater; it would simply rip through the planet and keep going on its merry way. That is because this figure is fifty thousand times too high. When we called H. Jay Melosh, University Distinguished Professor of Earth Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at Purdue University and author of many articles modeling meteor impacts, to ask him about this extraordinary number, he informed us that the shockwave would travel at roughly six kilometers per second. He was also generous enough with his time to correct a number of other assertions in Bryson’s account of the Chicxulub impact event. Some awards are easier to get than others, it would seem.

• • •

Speaking of large objects in outer space, when does a satellite become large enough to effectively function as a building? This question came up when we were editing William Firebrace’s essay in this issue. In print, the names of satellites—like all vessels’—should be italicized, per The Chicago Manual of Style. But the International Space Station looked very awkward to our eyes when it was rendered as the International Space Station, so we turned to the Arbiters of Style in Chicago. We are reproducing here our correspondence with them:

From: Cabinet <info@cabinetmagazine.org

>

Date: Monday, 22 June 2015

To: The Chicago Manual of Style

We are currently editing a text that includes a number of satellite names. We have italicized Vostok, etc., per Chicago section 8.115. But we now have a sentence that refers to the space stations Mir and International Space Station. Our feeling is that Mir should be italicized and International Space Station should not, but we can’t defend this since they are both proper names referring to the same exact kind of object (i.e.; a satellite, albeit one that is very large and can have multiple people living on it). Are these two to be treated the same as regular satellite names (e.g., Sputnik) and italicized? The fact that International Space Station is also functioning as a descriptor of the object makes it especially awkward-looking in italics. Any help would be greatly appreciated.

From: The Chicago Manual of Style <chicagomanual@press.uchicago.edu>

Date: Tuesday, 23 Jun 2015

To: Cabinet

Since Mir and ISS are the same kind of object, they should be treated in the same way. It’s an editorial decision, but they seem more like the names of buildings or communities or even projects than ships or vessels, and can therefore justifiably remain in caps only without further treatment.

All the best,

Staff

We appreciate the clarification but now live in dread of receiving an excellent text on, say, the history of the USS Intrepid and its transition from being an active ship in the US Navy to becoming the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum. Here is the kind of nightmarish italics scenario that such a text might put on our plate: “When the Intrepid was originally commissioned, no one imagined that it would one day become the Intrepid, a museum docked on the west side of Manhattan showcasing, among other things, the history of the Intrepid’s war service and its transformation into the Intrepid.”

• • •

We’ve always loved scratch-and-sniff films, where cinemagoers are given cards impregnated with various scents and asked during the film to release the appropriate odor for a given scene. The characters are eating pizza, say, and the cinema can be made to smell like a pizza parlor. While editing Stassa Edwards’s essay on the Great Stink of 1858, when the funk of London’s Thames finally overwhelmed the population, we were greatly helped by the matching olfactory ambience of our office, courtesy of a summer-warmed Gowanus Canal.

• • •

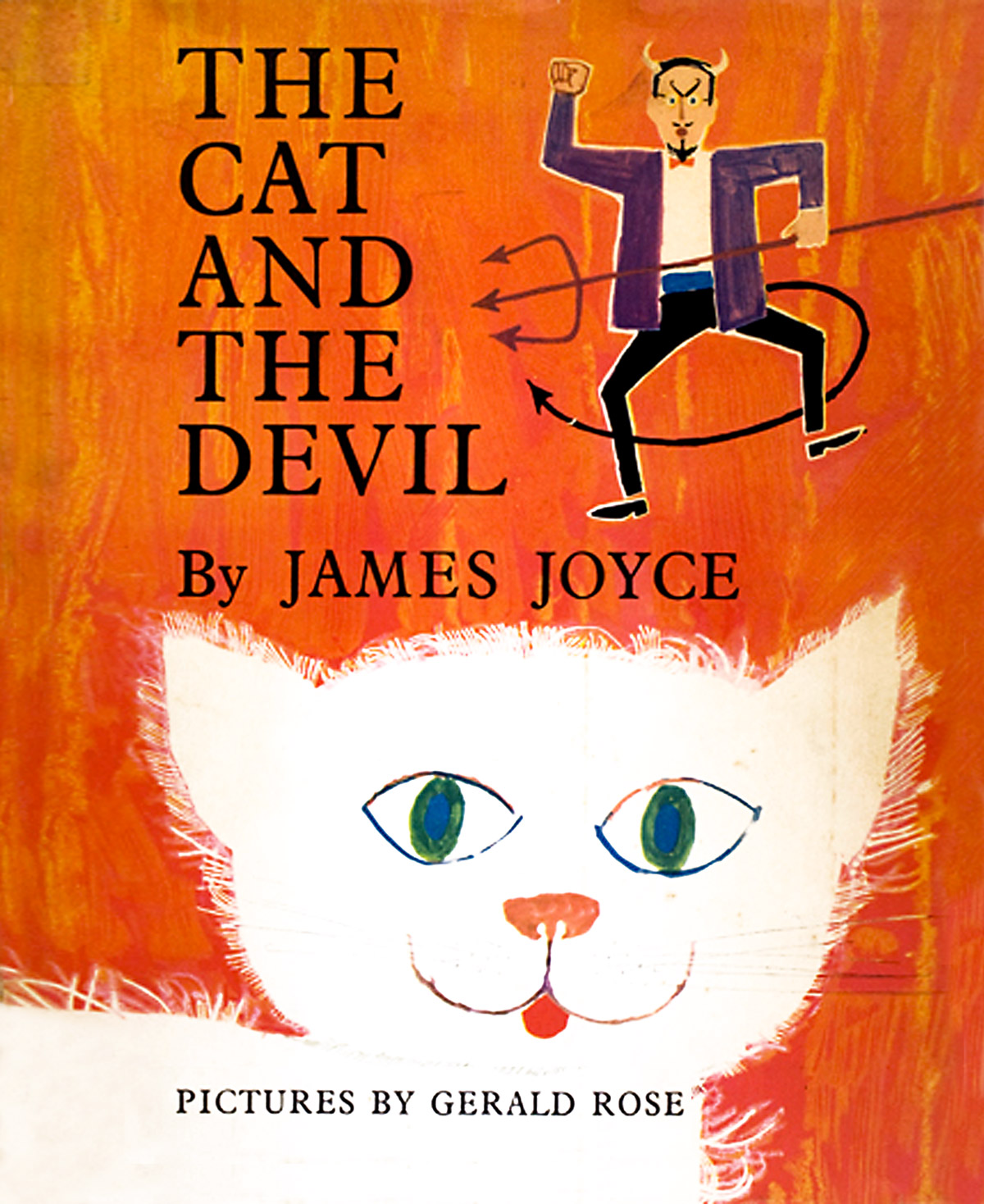

The Walter Benjamin text in this issue was hard to choose. He created many excellent radio broadcasts for children, and so many of them focused on terrible disasters! But reading Benjamin also reminded us of a time when intellectual giants did not think it beneath them to write books for children—Oscar Wilde, Daniil Kharms, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Langston Hughes, T. S. Eliot, Leo Tolstoy, and Ludwig Wittgenstein are only a few of the names to be added to Benjamin’s. We can’t vouch that all of them wrote great books, but it would be wonderful if someone revived the tradition, or at least sent us an essay on why it withered.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.