A Mind of Winter

The feeling of snow

Charlie Fox

Consider an author, alone in the snow. Vladimir Nabokov has frozen still, caught out between the past and present as he drifts back into the memory of a childhood winter, its distant sleigh bells ringing in his ears. “What am I doing in this stereoscopic dreamland?” he asks. “How did I get here?”[1] Suddenly no longer the small child with the puppyish gaze who spent “snow-muffled rides” hallucinating a role in “all the famous duels a Russian boy knew so well” but the impish old man of writerly legend, he rediscovers himself aged in his New England exile. (He and Vera have not yet left America to live at the foot of the snow-capped Alps in Montreux.) The memories are immaterial; “the snow is real, though, and as I bend to it and scoop up a handful, sixty years crumble to glittering frost-dust between my fingers.” So much is condensed in this handful of snow, now solid, now melting: a whole collection of memories and wonders. But what is the material supposed to mean? Perhaps you have to develop what Wallace Stevens calls, at the start of his poem “The Snow Man” (1921), “a mind of winter” to know.[2] Snow, like so many other materials, keeps its own special area in our thinking, and has its own blizzard of effects on our minds.

A more depressive survey than my own might be occupied by sketching out the imaginary equivalent of the Arctic across these pages. Indeed, snow’s richest metaphorical potential probably lies in its capacity to accurately map states of mental desolation, ranging from inertia to catatonia, through its exquisite blankness. But turn away from this icy eloquence and there are many other properties to be found, a full arc of thinking that curves from the trashy to the numinous. Snow coats reality in a fresh layer of strangeness. The psychological territory it occupies is vast and shape-shifting—if snow sends Nabokov into an elegiac mood, it can also account for great flurries of joy. The most logical response might be simply to play with it, following the thoughts that swirl through the mind as it responds to your attention.

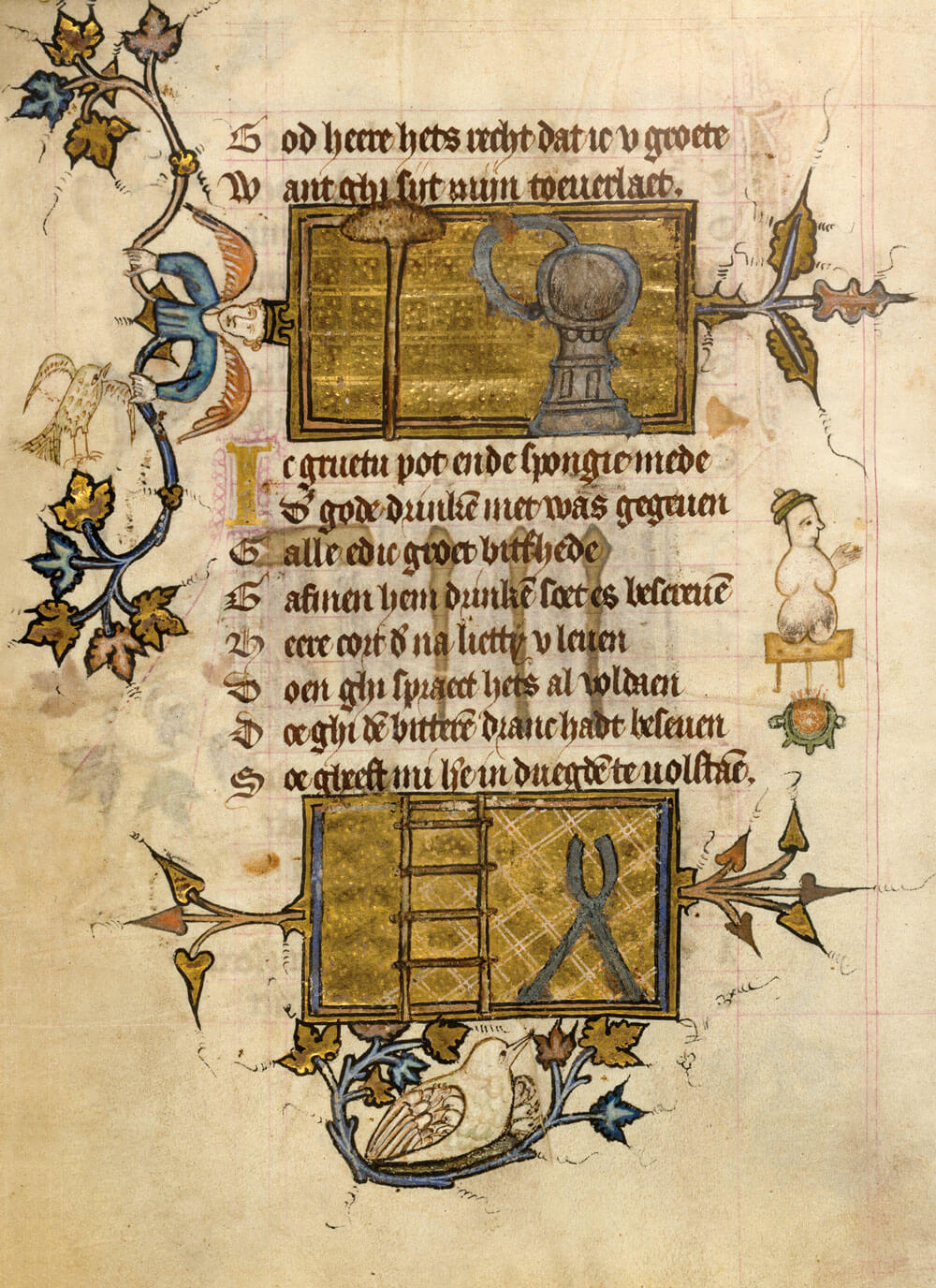

Bob Eckstein’s book The History of the Snowman (2007) is intended as a festive novelty, a goofy stocking filler, but examined with monomaniacal attentiveness over a dismal summer, it seems more like a thorough and eccentric work of anthropology: “The biggest niche in snowman retail is ... the artificial snowman industry. Plastic, Styrofoam, glass, wood, wool, silk, ceramic, Lenox, wax, rubber ... white chocolate, marshmallow, singing, dancing, lit up, blown up, hung up, strung out.”[3] Eckstein’s manic and materially various catalogue indicates the supernatural versatility of artificial snow, but also illuminates the discreet oddity of the snowman himself, a creature at once cuddly and cold. There’s a touch of cruel fairytale transformation—the fat man turned into a winter vagabond—lurking at the heart of these homemade sculptures as they cannily freeze the body, repurposing a carrot into a nose and coal into eyes. But this ingenuity with humdrum domestic stuff also supplies the snowman with a weird indigent charm, as if he were a jolly hobo paying a yuletide visit. He is a figure of fun, but you might wonder exactly what he represents for the family inside the house. A happy mascot with a balloon physique, the snowman keeps watch over the outside world. He might be a parody of the father or of all fathers and the gloom they supposedly exude, especially in Victoriana (cold, heartless, at some definitive remove from the orbit of the house), or a thrifty homage to an elder, signified by cozy but archaic accoutrements like the muffler and the pipe. The snowman could be an avuncular totem pole.

Beware the authentic snowman in decline, dying when the weather turns, because he seems to have stumbled out of a nightmare. The finest chronicle of this decline is David Lynch’s photographic project on snowmen.[4] As winter dwindled in early 1993, the filmmaker stole through the suburbs of Boise, Idaho, photographing the snowmen’s eerie struggle against the changing seasons. Lynch explained his fascination: “I don’t know who built the first snowman, but they always had coal for eyes and you’d put a pipe in there, and you’d put a muffler on him. That’s gone right out the window now. People do much weirder snowmen. … They’re made out of snow, which is a material you don’t get a chance to work with too often. And it really makes the human body look fantastic. I would like to take more pictures, because the houses behind the snowmen are also really interesting. And then the snowmen themselves are like aliens.”[5] Lynch treats his snowmen as freakish assemblages by unschooled artists, suggesting that far more monsters and phantoms run amok in the average mind than you might think, and giving extra unsettling life to that favorite theme of his films—the menace visiting the home. Lacking their traditional scarves or pipes, these snowmen look like lonesome ogres, huddled between little houses and witchy trees on lawns pockmarked with abrasive grass. Some have jack-o’-lantern grins and others are falling back into gnarly abstraction as time drifts on. With no full moon glow, the snow remaining on the ground is closer to a mean smear of industrial sludge than the spangled quilt you might dream about or find in melancholy winter films like Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955) and A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965). (Cartoon snow requires its own taxonomy: in The Simpsons, it glows, covering Springfield’s turf like whipped cream.)

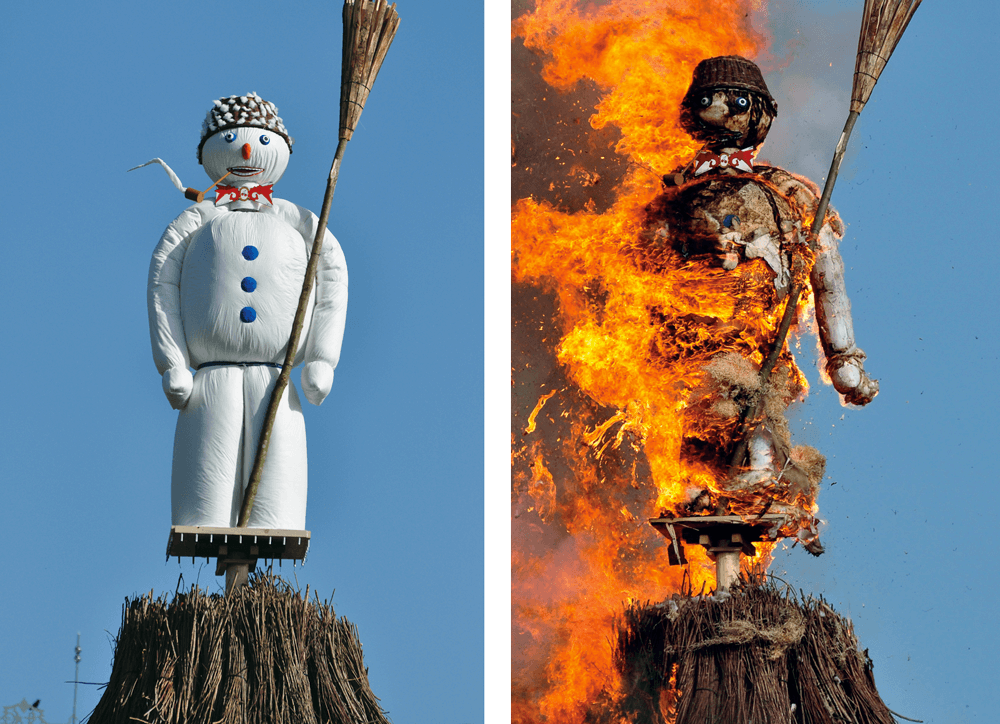

In addition to expending a good amount of genuine obsessive energy on such topics as “Early American Snowmen in the Seventeenth Century: New World, Fresh Snow” and “The Dean Martin Years: Drunken Debauchery and Other Misgivings,” Eckstein’s History of the Snowman is also instructive purely as a catalogue of whimsical practices and products. You can purchase, for example, inflatable snowmen as well as snowman kits, complete with “prefabricated hats” and “pseudo coal.” And he describes at length the annual Swiss spring festival Sechseläuten, which marks winter’s end by using a large amount of explosives “to blow up an innocent snowman”—a spectacle that combines the sacred pageantry documented in James Frazer’s The Golden Bough with the anarchic spirit of Looney Tunes cartoons. The best thing in Eckstein’s book might be the reproduction of a sweet but curiously eldritch etching on a chocolate box commemorating Sechseläuten. The wooden snowman—complete with fetching rustic feather cap and broom, his hollow body stuffed with fireworks—appears on the roof of a cart, a gargantuan schoolboy about to be heaved onto a bonfire.

• • •

On the afternoon of Christmas Day 1956, in a snow-covered field on the outskirts of the small Swiss town of Herisau, some children and their dog discovered the body of a dead man, hand clutched tight to his stilled heart. It was the writer Robert Walser, who had died that day, aged seventy-eight, while out walking far from the mental institution where he had dwelled for the previous two decades. A photograph taken by the local medical examiner Kurt Giezendanner shows the body at rest, left arm thrown out as in the style of a sleeper midway through a restless night, while two shadowy figures at the margins look on. The sorrow of the scene is rather gently assuaged by the odd fact that Walser’s hat, perhaps moved by a breeze, lies at a modest distance from his body, as if it has leapt off his head to cartoonishly express surprise at its owner’s death. A few distant trees squeeze into the top of the frame like awkward mourners paying their respects. The snow, even on the ground but for a few shaggy lumps close to his boots, appears at first to be nothing more than a dazzling absence, as if the dead Walser were floating on a white winter sky.

In his essay on Walser, William H. Gass takes the perspective of one of those marginal witnesses and studies the photograph as a peculiar abstraction: “I like to think the field he fell in was as smoothly white as writing paper. There his figure … could pretend to be a word—not a statement, not a query, not an exclamation—but a word, unassertive and nearly illegible, squeezed into smallness by a cramped hand.”[6] Another photograph of the scene by the medical examiner taken from a different angle reveals the fateful trail of footprints—the only other marks in the snow. Examine them with a Gass-like slant and they become an ellipsis on this near-blank page, trailing away from a last, unfinished thought.

In his prose, Walser assumes the voice of a bewildered innocent, neither a child nor a full-grown man, enchanted and unsettled by the surrounding world. Snow was certainly something that fascinated him, and perhaps left him a little scared: “If there is snow, everything is soft, it’s as if you were walking on a carpet.”[7] Before this comes the little wonder of watching snow fall “slowly, that is, bit by bit, which means flake by flake, down to the earth.”[8] The schoolboy narrator of Fritz Kocher’s Essays adores snow because it smoothly removes the loud distraction of color from the landscape: “Colors fill up your mind too much with all sorts of muddled stuff. … I love things in one color, monotonous things. Snow is such a monotonous song.”[9] The empty page might be a snowscape, waiting to be blackened with words, but maybe the opposite thought is beautiful, too: words, like snow, slow the world down, inventing a quiet that can be vanished into and inhabited. John Ashbery imagines reading such a page (white on white) in his poem “The Skaters” (1966): “Words fly briskly across, each time / Bringing down meaning as snow from a low sky.”[10]

• • •

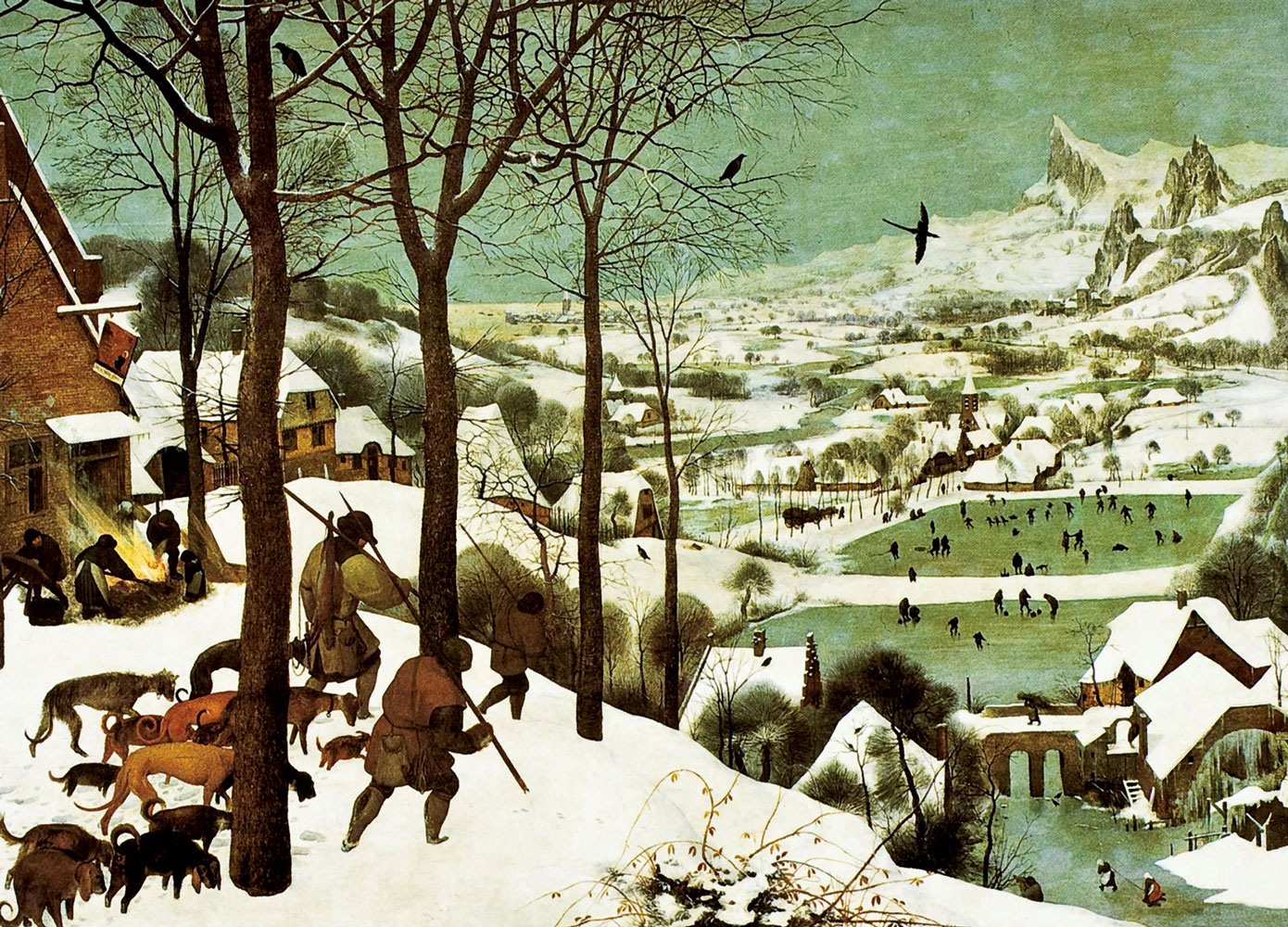

Hollywood now relies on innocuous paper snow or computer trickery to create its winter wonderlands, but the history of this special effect is far more sinister. From the 1930s to the 1950s, asbestos fibers were repurposed as a low-price snow simulant for use in both domestic decorations and cinematic landscapes. The toxic substance was sold in gaudy boxes that bore names like White Magic and Snow Drift and featured cartoons depicting dreamtime scenes—vanilla ice cream snowscapes, velvet skies, expressionless children in snowsuits (no trolls, no witches, no carcinogens), and stars scattered like powdered sugar around the cake of the moon. Always depicting a backyard Narnia, these kitschy scenes exist within a cultural tradition where winter turns domestic. Thoughts of lupine hunger are banished, and the season is transformed into summer’s Nordic cousin: heartwarming and inviting endless play in the open air, despite the gathering chill. (Classical example: the frolics in the hinterland of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Hunters in the Snow from 1565.) There’s also a surreal sensory jolt induced when you come across the reality-distorting phrase “fireproof snow” on certain boxes, rhetoric designed to position the material as a safe option for your cozy home.

But that’s snow’s greatest mythic property, its paradoxical power to convey warmth (the proverbial “warm and fuzzy” feeling induced by a sentimental or festive mood), an affect that would be much more difficult to transmit through some winter scene depicting, perhaps, an enchanting mirror of fresh ice on a lake.[11] Remember that moment in The Wizard of Oz (1939) where the bewitched ruby-red poppy field sends Dorothy, Toto, and the Cowardly Lion to sleep. Only the Good Witch’s counterspell—a sudden flurry of snow—wakes them. Poor Judy Garland comes to amid the stalks, coated in fantastic dust. “Unusual weather we’re having, ain’t it?” cracks the Cowardly Lion in the sunshine, not knowing that the snow has rusted the Tin Man’s joints once more. The presence of this little toxic cloud floating over everybody’s favorite Technicolor fable is maybe just ghoulish trivia but the scene offers, too, a woozy meditation on the magic of art, especially its power to transform or tame weather and remake it as a sweet illusion.

“Unusual weather” also sweeps through William Dieterle’s Portrait of Jennie (1948), the most luxurious artificial snow reverie from Hollywood’s golden age. A love story coated with a creepy psychological frost straight from Edgar Allan Poe—doomed artist goes to the edge of madness in his attempt to capture the titular heroine in all her will-o’-the-wisp beauty—the film is a lavish mash note from its producer David O. Selznick to Jennifer Jones, its star and his new bride. A penniless painter (Joseph Cotten) is out roaming New York City on a ferocious winter evening during the Great Depression, when who should he encounter in Central Park but Miss Jones, playing a saucer-eyed nymph. He’s immediately spellbound by this innocent adolescent wearing schoolgirl plaid and rabbit-paw mittens, but she disappears after a little playful conversation, not even leaving a footprint behind. At their next meeting, he discovers that she’s the orphan daughter of high-flying—and falling—trapeze artists. The painter and the girl develop a fey friendship, all hot chocolate and chilly breath, as he grows ever more obsessed with her. Jennie is captured in an early charcoal sketch as a doll-like little creature at the end of a twilit avenue, enclosed by a protective roof of haggard branches.[12]

With every fresh encounter, Jennie ages, growing from perky fawn to near-adult maiden in the course of the story, and soon it becomes clear that she’s nothing but an apparition. Vanishing and returning according to her own dreamy whims, Jennie is a symbol for the vagrant nature of inspiration, and, of course, other febrile desires: “I wanted more than just dreams,” Cotten confesses in his nighthawk voice-over, “but that was impossible.” Snow—strewn over the dark streets in fluorescent marble chunks, laid flat in an angel’s-eye view of the park like sparkling glass, or settled, snug, on the earth like an animal’s fur—turns the city into a drowsy little world. This enchanted climate indicates an erotic condition—a frozen longing—that finally thaws when Jennie reaches adulthood with the spring. Monochrome, too, dissolves into wild-sea green at the finale, which is in turn a mere warm-up for the Technicolor epilogue where the long-dreamed-of portrait is unveiled. (Selznick hung this real treasure in their house.) It’s a faithful trick from Gothic fiction, making the weather into a barometer for a character’s moods: snow manifests a state of mind.

• • •

Gaston Bachelard’s response to snow is cool, conspicuously lacking the kind of boyish glee found in Walser’s writing. In The Poetics of Space, he observes that “snow … reduces the exterior world to nothing rather too easily.”[13] Why swoon over snow with its far too obvious charms, Bachelard asks, when you can find the subtle thrills that come from studying a shell or a bird’s nest? But his writing on snow has its own uncommon beauty, recording with the same careful attention found in Walser’s prose just how this shift in the weather reshapes our thinking and transforms our surroundings. Though he’s reluctant to find solace in the monochromatic, or to be wholly lured by its seductive nothingness, he remains a masterful chronicler of its lulling, narcotic effects. Snow “covers all tracks, blurs the road, muffles every sound, conceals all colors.”[14] For those within the house, it encourages the profitable hibernation that gives rise to new reveries and dreams. Time turns misty: “on snowy days, the house too is old. It is as though it were living in the past of centuries gone by.”[15] As the world beyond the house is turned into a “diminished entity” by the weather, the thoughts of its inhabitant (always, for Bachelard, the solitary “dreamer of houses”) can resonate with greater intensity.[16] A double retreat to the interior is staged, at once into the house and further into the shelter of the mind.

Here, in this fading light, you can see where snow falls in what the poet and critic Bruce Hainley has wisely called “the psyche’s meteorology.”[17] Slowly, it activates reverie, daydreaming, and digression within digression. Perhaps this is not only because it temporarily hushes the flow of the outside world, but because its appearance (remaking a field as a map gone blank) lays out a space approximating an empty mind. In this climate, thinking wanders or stops still, allowing you, as Stevens wrote in “The Snow Man,” to “behold nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

The first caption in this article, which incorrectly stated that the photographs of Walser’s body in the snow were taken by his friend Carl Seelig, was corrected on 7 August 2016.

- Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 66. The hallucinated duels appear on page 152.

- Wallace Stevens, “The Snow Man,” in Complete Poetry and Prose (New York: Library of America, 1995), p. 8.

- Bob Eckstein, The History of the Snowman (New York: Simon Spotlight Entertainment, 2007), pp. 45–46.

- See David Lynch, Snowmen (Paris & Göttingen: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain & Steidl, 2007) and David Lynch, Images (New York: Hyperion, 1995).

- Chris Rodley, ed., Lynch on Lynch, rev. ed. (London: Faber & Faber, 2005), pp. 217–219.

- William H. Gass, “Robert Walser,” in Finding a Form (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), p. 65.

- Robert Walser, “Winter” in The Walk, trans. Christopher Middleton et al. (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2013), p. 126.

- Ibid., p. 127.

- Robert Walser, “Autumn,” from Fritz Kocher’s Essays, in A Schoolboy’s Diary and Other Stories, trans. Damion Searls (New York Review Books: New York, 2013), p. 6.

- John Ashbery, “The Skaters,” Collected Poems, 1956–1987 (New York: Library of America, 2008), p. 149.

- Right down to the frisky italics on “warmth,” this discussion of myth obviously has Roland Barthes’s sensualist fingerprints all over it, though he devotes little space in his omnivorous works to snow beyond that lovely vision from Mythologies (1957) of Greta Garbo in Queen Christina (1933) and “her snowy solitary face.” For a more thorough investigation of the semiotics of snow, hunt out Gilbert Adair’s neat essay in his collection Surfing the Zeitgeist (1997): “What a coating of snow provides is the winter’s equivalent of a beach,” and his splendid classification of snow as the “raw, powdery material of nostalgia, existing either in the past as a memory or in the future as a dream.”

- Perhaps it’s no surprise that the novella from 1940 of the same name by Robert Nathan, on which the film is based, was a favorite of the artist Joseph Cornell. (He also kept a dossier on Jennifer Jones in his legendary basement in Queens.) The film and the book are an index of Cornell’s obsessions: winter, circus lore, wondrous but ungraspable girls, nineteenth-century New York, art’s capacity to stop time, etc. The domain of his work is uncannily forecast by a mournful line in the voice-over: “The world of my art remained an empty box.”

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), p. 40.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 41.

- Ibid.

- Bruce Hainley, “Seen and Not Seen: Maureen Gallace,” Frieze, no. 57 (March 2001). Available at https://www.frieze.com/article/seen-and-not-seen-0.

Charlie Fox is a writer who lives in London. His book, long thought to be about recluses, has lately changed shape.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.