I Feel It Is My Duty to Speak Out

The disingenuousness of the Silk Cashewmilk makeover

Sally O’Reilly

Dear WhiteWave Foods,

I am writing to complain about one of your products: namely, Silk Cashewmilk (with a touch of almond). I imagine that you receive many complaints about your use of the word “milk,” and frequent challenges to specify where exactly on the cashew nut the teats are located. This, however, is not a problem for me, since I simply mop up what I take to be a sloppy euphemism with a pair of quotation marks. No, what I wish to complain about is the recent redesign of your half-gallon “milk” cartons.

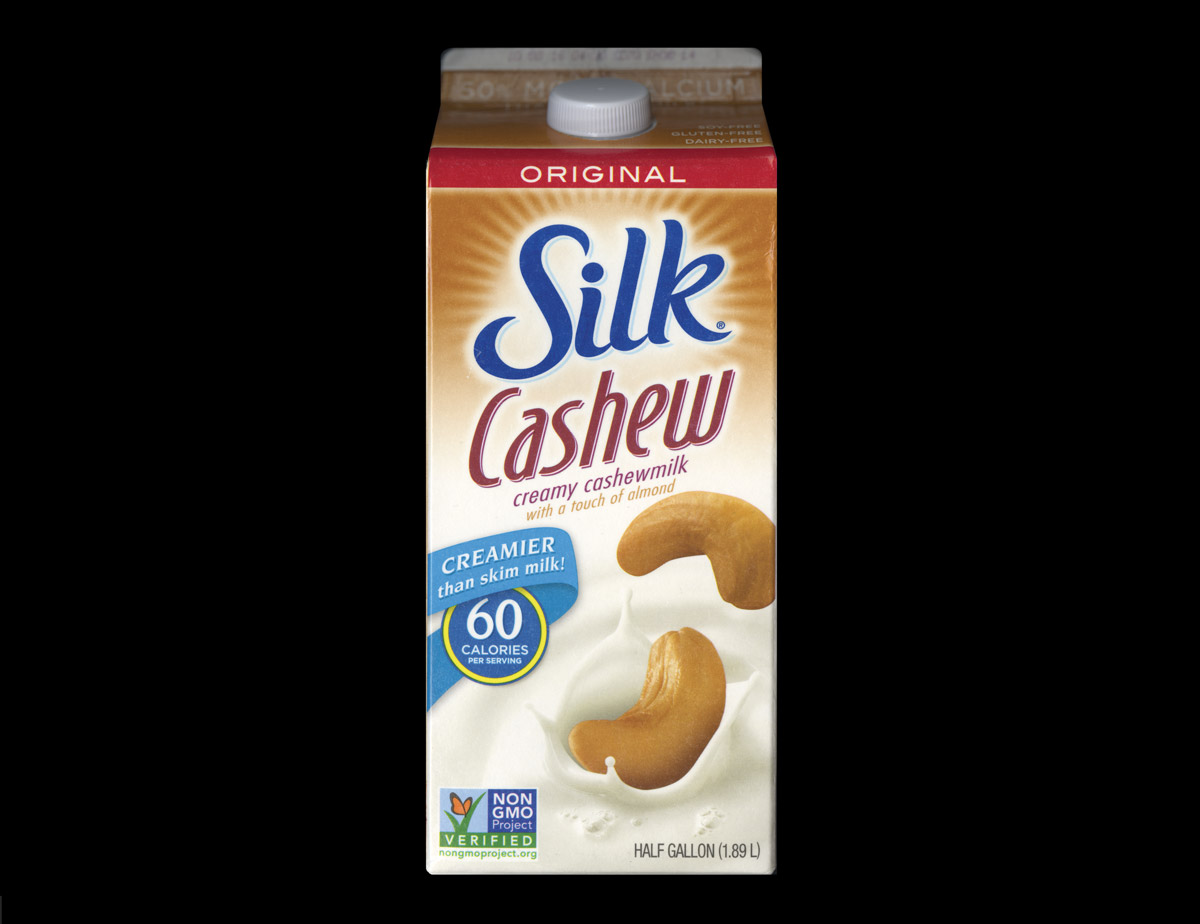

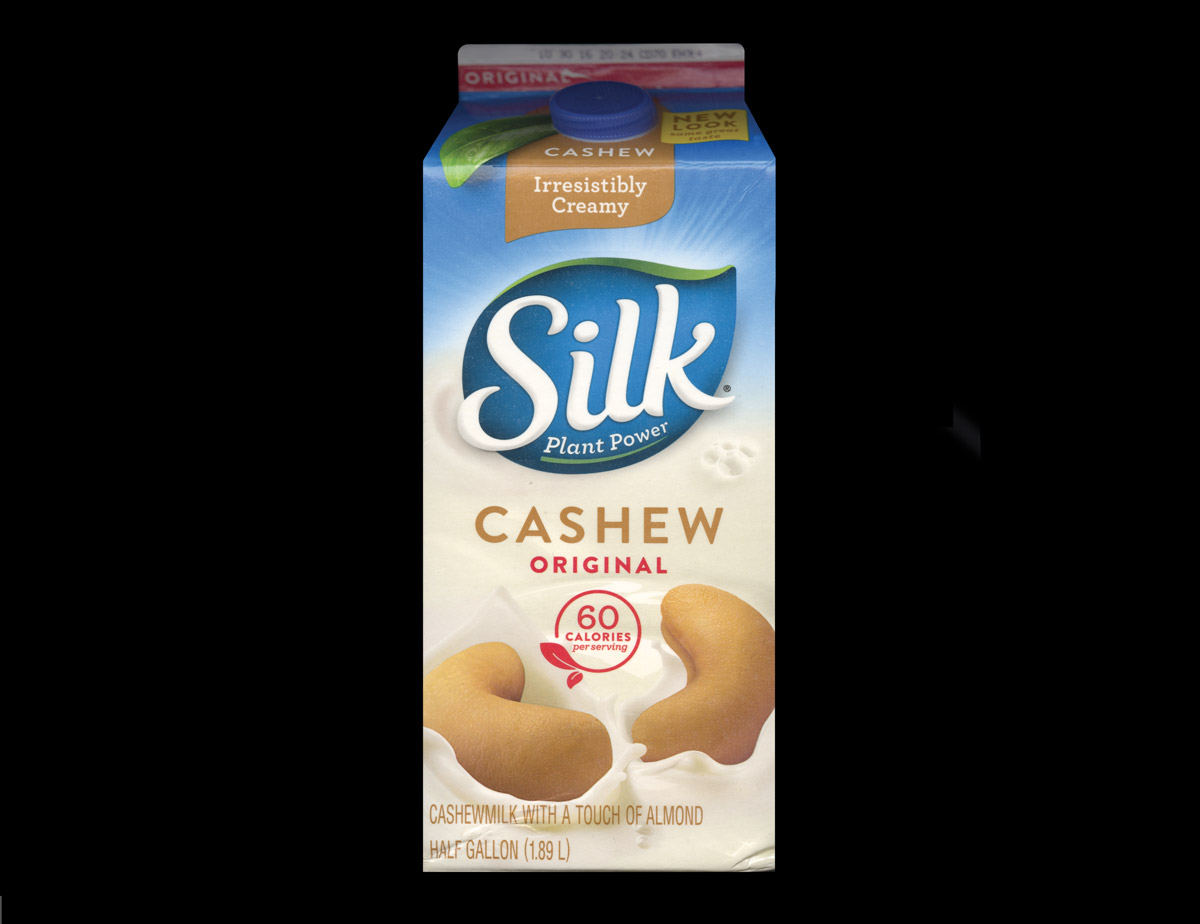

My bipartite beef with this redesign is 1) the reduction in realism of the illustration and 2) the stance of the nuts represented therein. To start with the latter point: I have come, in recent years, to identify with the two nuts who, like game siblings, plunge pell-mell into their fate. I hope that it is not an anthropomorphism too far to suggest that one splashes down as if propelled from a water chute, and the other arcs forward, as if diving headlong, emboldened by the first’s joyful splash. This is an image of excitement and of freedom (from what, I presume, is for the “milk” drinker to decide). In the new arrangement, however, the two nuts face one another, turning their backs on the world to assume a conservative relation based in partnering and stability. My concern is that here you are affirming and perpetuating recent troubling shifts in political attitudes the world over. Your open and energetic cashews have become inward-looking; even their spatial alignment is now in almost complete agreement with one another, as if no differently oriented nut would be welcome.

The medium into which they are about to be subsumed has similarly been made safe. You have, it seems, seen fit to censor the milk-droplet coronet of the earlier packaging—which was, I felt, a nod to the pioneering photographic work of A. M. Worthington at the turn of the twentieth century, and a salute to the spectactularist high-speed film experiments of Harold Edgerton some fifty years later. The new design suppresses the tremendously uplifting splash motif, implementing instead what might be described as a mellifluous swelling of liquid about the nuts. This is no doubt to draw on connotations of silk, to visually insinuate the creaminess that the tongue can look forward to. Well, for one thing, a tongue cannot look. And for another, I do not need such synesthetic cues or Elysian fictions to aid me in my beverage choices. And for yet another, you have likely alienated your buyer base of thrill-seeking individualists with this new appeal to comfort-loving sensualists. This smacks to me of playing to the risk-averse majority; but then again yours is, I would feel confident in submitting, a numbers game above all else.

On the subject of harsh realities, I come back to my first point: the illustration’s insulting retreat from realism. The previous packaging was so bracingly candid about the earthy origins of the nut. Not only were we invited to contemplate the somewhat irregular seam at which the two halves fuse, we were also treated to a well-lit view of the surface of the nut, ridged and pitted like the craggy face of an ancient poet. I could admire these nuts that had passed into “milk” with dignity and originality. The new protagonists, however, have been airbrushed and plumped up; they appear not to exist in any reality that I can identify with, but to hail from the pulpiest of fictions, and one that ends in an improbable perpetuity.

We all know that food photography lies—that the ice cream is mashed potato, that the meat is seared with shoe polish, that the milk, or “milk,” is PVA glue or hair conditioner or suntan lotion. I understand that the look or sound of reality must be constructed to be convincing. But it is not the material lies you tell so much as the conceptual maneuvering that strikes me to the core. What are you trying to hide from us? What is it that you think we cannot handle?

Is it the cashew apple that you are so desperate for us to forget about, or to not even know of in the first place? Do you forsake the pear-shaped fruit that puckers indecently around its ovary (which is so chauvinistically called the nut)? Or is it the cashew bark exudate that you renounce as a substitute for gum Arabic and deny is employed as adhesive, insect repellent, and a lubricant in the electrical insulation of airplanes? Or do you wish to bury the pompous initialism CNSL, because, when pricked, it turns out to stand simply for cashew nut shell liquid—that caustic goop used in brake linings and bioplastics, and which, when it comes into contact with the skin, or even if inhaled, can cause a pruritic rash on the extremities, torso, groin, axilla, and buttocks, and, less commonly, a perianal itch or a blistering of the mouth, and, even less commonly, can transform ears into “large red terra-cotta classical casts of ears,” as happened to the poet Elizabeth Bishop?

There is much about the cashew tree that I, and many others, are kept ignorant of. I would have thought you would be proud of the impressive company that it keeps as a member of the order Sapindales. Why not crow from the forest canopy that your product is related to the delicious mango, citrus, maple, lychee, and sumac trees, and to the historic big-hitters frankincense, myrrh, and balm of Gilead? Why not capitalize on its prestigious relatives the mahogany and the West Indian cedar, which furnish fine rooms and cigar boxes, respectively. Why remain quiet about its rubbing shoulders with the Ceylon oak, which is the source of Macassar oil, and the buckeye, which is used to make artificial limbs and paper and to stun fish? I can guess why. Because you do not wish us to know that it is even more closely related to the poison oak, poison ivy, and poison sumac. What the tranquil fiction that you feed us cannot admit is that this food originates as poison, that it is only through decortication and heat treatment that it is rendered food.

And yet I can cope with this sort of knowledge. I am perfectly at home with potatoes, for instance.

Perhaps I am mistaken in laying the blame with you. Perhaps it is the phalanx of official bodies that does not trust me to believe that shell liquid, sap, and “milk” are different. Is it the combined might of the African Cashew Alliance, the African Cashew Initiative, the National Council of Benin Cashew Exporters, the Brazilian Cashew Nut Manufacturers’ Association, the World Cashew Nut Alliance, and the Vietnam Cashew Exporters’ Association that silences you? Or do the International Nut and Dried Fruit Council, the Combined Edible Nut Trade Association, or the International Nut Council tie your hands on the matter? (Although I don’t imagine the Californian Dried Plum Board or the American Peanut Council would gladly suffer the impositions of these last three generalists.)

If what I have inferred is indeed the case, then, as a valued consumer of your product, I can only convey my disappointment at your perviousness to political pressures. I hereby also express my hope that, at your next design summit, you will seek an alternative packaging solution that is as courageous and principled as it is affecting.

Yours sincerely,

Sally O’Reilly

Sally O’Reilly is a UK-based writer. Her recent projects include the novel Crude (Eros Press, 2016), and the libretto for the opera The Virtues of Things (co-commissioned by the Royal Opera, Aldeburgh Music, and Opera North, 2015). In 2016, she had a year-long writing residency at Modern Art Oxford.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.