Cinematic Airs

The battle of the “smellies”

Christopher Turner

In Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel, Brave New World (1932), the Bureau of Propaganda has invented the “feelies,” which bring tactile effects to popular entertainment. By holding special knobs on their chairs, audience members could enjoy titillating experiences such as “a love scene on a bearskin rug” between “a gigantic negro and a golden-haired young brachycephalic Beta-Plus female,” almost as if they were there. In 1929, Huxley had seen his first talkie, The Jazz Singer (1927), which he described as “the latest and most frightful creation-saving device for the production of standardized amusement.” He was dismissive of the movies, believing cinemas were great factories of political distraction, where crowds soaked in “the tepid bath of nonsense. No mental effort is demanded of them, no participation; they need only sit and keep their eyes open.”

In the novel, Huxley’s central character attends a screening of the feely Three Weeks in a Helicopter, billed as: “AN ALL-SUPER-SINGING, SYNTHETIC-TALKING, COLOURED, STEREOSCOPIC FEELY WITH SYNCHRONISED SCENT-ORGAN ACCOMPANIMENT.” This introduction of smell into theater was not without precedent. In 1868, for a production of The Fairy Acorn Tree, smells were dispensed around the Alhambra Theatre in London with “vapourisers.” And it is at the Alhambra where Three Weeks in a Helicopter is screened in the novel. Oscar Wilde, considering the staging for an 1892 production of his play Salome, imagined “in place of an orchestra, braziers of perfume … a new perfume for each emotion,” and during MGM’s Hollywood Revue (1928), an orange aroma was released when Charles King sang “Orange Blossom Tree.”

Huxley’s feely, described by one character as “first-rate,” begins with an overture played on the scent-organ, to which the audience sniff and listen, transported by a “delightfully refreshing Herbal Capriccio—rippling arpeggios of thyme and lavender, of rosemary, basil, myrtle, tarragon; a series of daring modulations through the spice keys into ambergris; and a slow return through sandalwood, camphor, cedar and new-mown hay (with occasional subtle touches of discord—a whiff of kidney pudding, the faintest suspicion of pig’s dung).” The film, in accordance with a culture that uses free love and sexual satisfaction as a form of social control, soon descends into pornography, and it remains unclear what role smell plays in the gymnastic gyrations that send an electric thrill through the audience. Other polysensuous extravaganzas referred to in the novel include “the famous all-howling stereoscopic feely of the gorilla’s wedding” and The Sperm Whale’s Love-Life, which made joking reference to contemporary science documentaries, a form Huxley actually admired, including his purported favorite, The Sex Life of Lobsters.

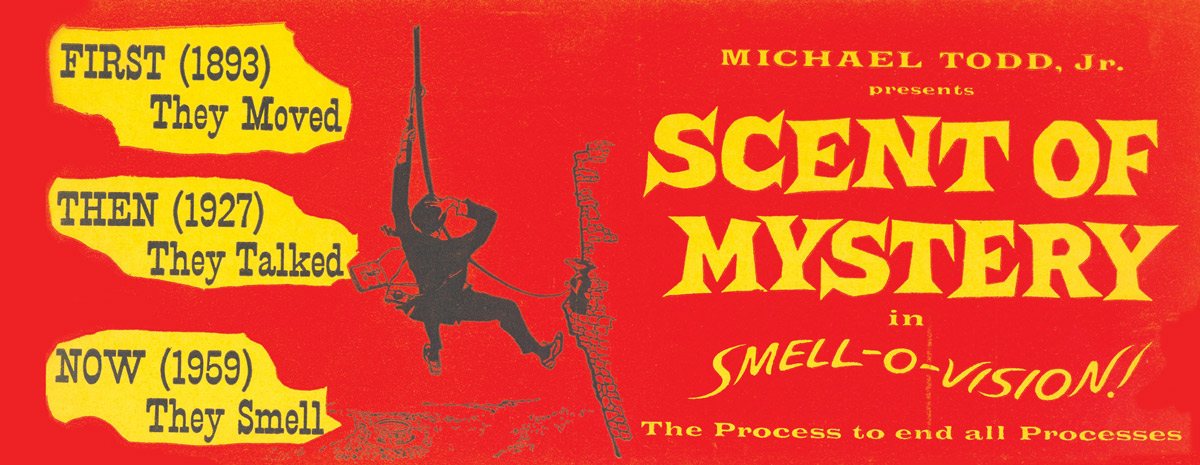

In 1938, Huxley emigrated to Hollywood, where, ironically given his disdain for cinema, he worked as a scriptwriter. He was tasked mainly with adapting literary classics, but also attempted, unsuccessfully, to bring Brave New World to the screen. In 1956, he even proposed transforming it into a three-act “musical comedy,” complete with numbers like “Everybody’s Happy Now” (which all sounds a bit too much like “Springtime for Hitler” in The Producers). Despite pitching the idea to his friend Charlie Chaplin, this bizarre scheme unfortunately also went unrealized. Notably, in his script, Huxley made the choice not to stage the feelies, deeming the representation of its multisensuous possibilities unfeasible on screen. However, in 1959, influenced by Huxley, two American films were made that used ambitious technology in the attempt to do just that, by introducing smell to cinema. The poster for one proclaimed: “FIRST They moved (1893) THEN They talked (1927) NOW They smell (1959).” The films premiered in December 1959 and January 1960, and the press dubbed their rivalry “The Battle of the Smellies.”

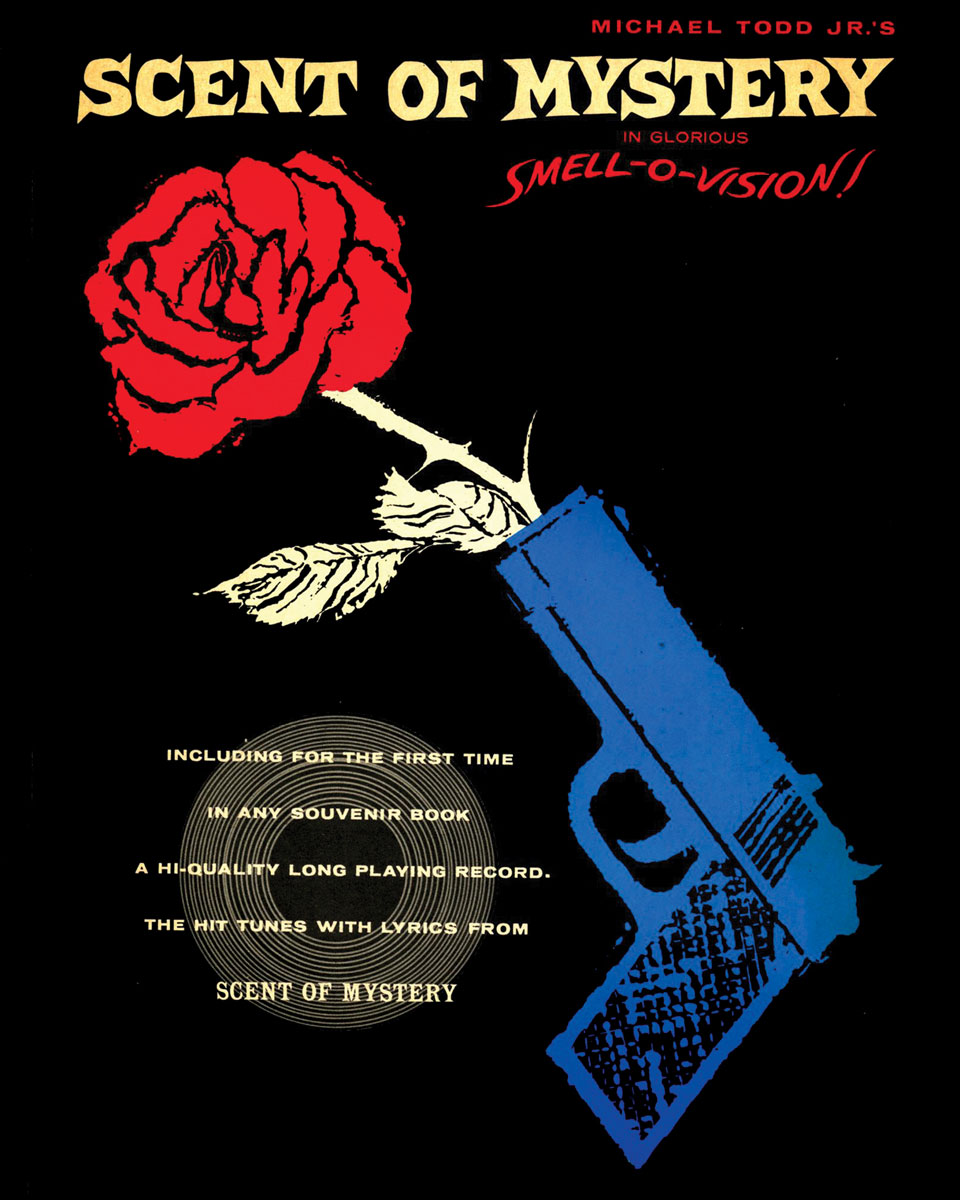

The two films were Behind the Great Wall, made with the Aromarama system, conceived and developed by public relations executive Charles Weiss; and Scent of Mystery, which used the Smell-O-Vision process promoted by Mike Todd Jr., son of the legendary theatrical impresario and producer of the same name. By the late 1950s, television was in ascendency, and the movies sought to innovate—with 3-D, wraparound 360-degree screens, and the “smellies”—in order to see off this existential threat. Weiss showcased his technology, which used aerosol canisters to inject fragrances into the cinema’s general air supply system, with a travelogue, a sweeping panorama of China featuring Buddhist temples and Mongol warriors that had already won prizes at the Venice Film Festival and the Brussels World’s Fair. It was given a smell track that featured the aromas of floral processions, fireworks, and construction sites, the spicy scents of Hong Kong’s street markets, and the burned resin odors of a tiger hunt.

The documentary was first shown in December 1959 at the DeMille Theater in New York, which was converted for the task at the cost of $7,500. A triggering device was connected to the projector and electronic precipitators acted as “deodorizers” to filter the air between smells. However, the New York Post wrote: “The great green outdoors upon one occasion came through as celery tonic.” Bosley Crowther in the New York Times further elaborated on the film’s flaws: “In between the suffusions of odors, the air in the theatre is cleared by a purifying treatment that itself leaves a sticky sweet smell, which tends to become upsetting before the film has run its full two hours. When this viewer emerged from the theatre, he happily filled his lungs with that lovely fume-laden New York ozone. It never has smelled so good.”

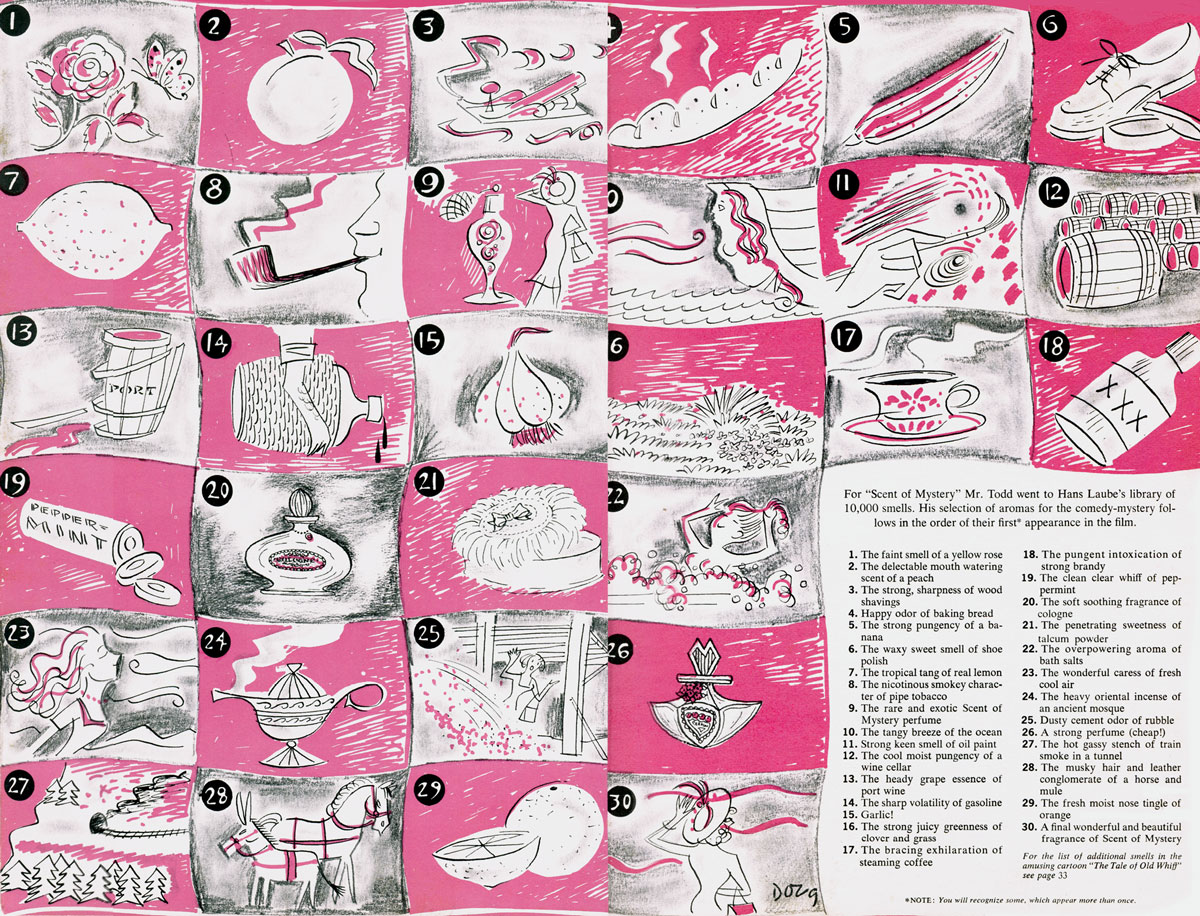

In contrast, the more sophisticated Smell-O-Vision process, used for the comedy-mystery film Scent of Mystery, cost $30,000 to install and allowed smells to dissipate naturally into the air. The odors were manufactured by Professor Hans Laube, a former advertising executive from Switzerland turned “world-renowned osmologist.” According to his daughter, Carmen, he thought that everything had a smell, including emotions; he once asked her to throw open the window because the room stank of ego. Laube was the inventor of a method for clearing the air in large auditoriums, and a logical extension was that he could also pipe smells in. He had shown what he called a Scentovision film, featuring several odors, as early as 1939 in the Swiss pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, which was also host to Michael Todd’s Hall of Music, featuring live performances by Gypsy Rose Lee. The Todds, known for their theatrical stunts and pioneering new processes, had been contemplating making a smell film for almost a decade, but it is unclear whether they first got wind of a feasible technology there. In 1943, the New York Times reported that Scentovision “produced odors as quickly and easily as the soundtrack of a film produces sound.”

There is a publicity picture of Todd Jr. and Laube sitting either side of the Smell-O-Vision master control system, or “scent energizer,” which resembled a complex piece of scientific machinery. It was described in the souvenir program as a “mechanical monster”: “Made of stainless steel, specially treated rubber, and glass, it looks like something out of an Atomic plant.” The device, manufactured by Belock Instrument Corporation, housed a carousel of eight-inch vials each containing the highly concentrated essence of a specific scent, and had a bank of dials to regulate the concentration of odors. The 1,100-seat Todd Cinestage Theatre in Chicago, which Todd Sr. had bought and fitted with a wide, curved screen to show Around the World in Eighty Days (1956), was used as a laboratory for the new technology. On the back of each seat was fitted a tiny, black pipe, about three-quarters of an inch in diameter, with a spray nozzle at the tip to project smells to the viewer. A mile of pipework ran under the floor, and each nozzle was connected to the “smell brain,” the huge dispensing machine that stored all the aromas to be projected. An extra track on the film carried the smell signal, which would send an electronic pulse to trigger the mechanism. A needle would then draw two centiliters of concentrate, enough to fill the auditorium, and with a faint hissing sound, right on cue, a small cloud of aroma would reach every seat in the house simultaneously.

Scent of Mystery was directed by the British director Jack Cardiff, who was known as the “Grand Master of Technicolor.” He had worked as a cinematographer for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger on Black Narcissus (1947), for which he won an Oscar, and The Red Shoes (1948), and he had joined John Huston in an awkward tropical shoot for The African Queen (1951). Cardiff had just made the move to directing when Todd Sr., who had wrapped Around the World in Eighty Days, approached him to make an adaptation of Don Quixote. However, Todd died in a plane crash over New Mexico in March 1958, and the project was shelved. His son, who was keen (and now able) to emerge from his showman father’s shadow, approached him to make Scent of Mystery instead. Cardiff was enthusiastic about shooting a $2 million “picture for the third sense.” In the 1930s, he had made travelogues about Rome, Naples, Jerusalem, and the Bedouin in the Jordanian desert, and he decided to shoot the film entirely on location in Spain. (Todd Jr. had also first distinguished himself as the unit manager for documentary sequences about Niagara Falls and the canals of Venice.) It was shot using the special, widescreen “70mm Todd Process Camera,” which gave an uncanny depth of field, adding an effect of hyperreality to the sumptuous Spanish scenery.

I had been trying to track down Scent of Mystery for years—it was missing from the British Film Institute archive, and all others I consulted—and I once wrote to Cardiff to ask if he had his own copies of the reels, but he was too ill to reply. (He died in 2009.) However, the film was recently reissued on DVD by Redwind Productions as Holiday in Spain—without the smell track, of course. It was amusing to watch it with only the illustrated list of thirty smells, printed in the program that accompanied the original screening of Scent of Mystery, to indicate the odors, without any clue as to when to expect them. (Helpfully, this souvenir pamphlet is reproduced with the DVD.) The dramatic point of crucial scenes was woven into the actual presence of a smell. For example, the camera lingers on bread for an unnaturally long shot, and you know that you’re supposed to smell the delights of baking; or, a villain runs down a staircase to escape several rumbling casks, which crush him, and the camera pauses on his lifeless body, pickled in what you know to be the strong aroma of wine.

In 1981, John Waters released Polyester with an “Odorama” scratch-and-sniff card that parodied things like Smell-O-Vision. Waters’s storyline featured Divine as Francine Fishpaw, a renifleur—someone who is sexually gratified by odors—and the audience had to scratch the smell card when the corresponding number flashed up on screen. These included the smell of farts, socks, and roses, that were basically distinguishable in scratch and sniff only as sweet and sour. I could imagine the illustrated list of smells for Scent of Mystery as a similarly pungent board game, every move on which secreted an olfactory delight: “1. The faint smell of a yellow rose 2. The delectable mouth watering scent of a peach 3. The strong sharpness of wood shavings 4. Happy odor of baking bread 5. The strong pungency of a banana.” There was also garlic, wine, gasoline, talcum powder, gun smoke, brandy, incense, train fumes, and even fresh air.

The film opens with a drifting, panning shot, made from a helicopter-borne camera, that follows a superimposed butterfly as it flutters into the garden of the Alhambra (appropriately the name of the cinema where Three Weeks in a Helicopter is screened in Brave New World). It alights on a flower, and the audience would have received their first smell, a rose-scented whiff of perfumed air. The second aroma would have hit them when they first encounter Peter Lorre, who plays a taxi driver and is leaning against his car devouring a ripe peach. Lorre, a fat, squat man with bulging, rolling eyes, was perhaps best known for playing a pedophile in Fritz Lang’s M (1931). He suffered a sudden heart attack during filming in Cordoba. Local doctors diagnosed him with blocked arteries, which they alleviated by using bloodletting, an ancient technique that seemed to work. Cardiff had to advertise for a Spanish double to cover him until he could return to the set and, even then, to do any running or other exertion.

The audience had to wait for smell No. 9, “The rare and exotic Scent of Mystery perfume,” for the crucial, recurring clue to solving the murder mystery that unfolds. Our hero, Denholm Elliott (Cardiff originally cast Peter Sellers, a suggestion Todd rejected, and one can’t help wishing it was him in the role), has seen a mystery woman in a large hat walking away from him and, having apparently fallen in love with her on the basis of her lingering smell, believes she is in great danger. He spends the entire movie chasing this elusive scent around Spain, shadowed by the murderer, who is identifiable from his tobacco smoke. Eventually, after sliding down a wire using his umbrella to save her from certain death, we smell No. 30, the “final wonderful and beautiful fragrance of Scent of Mystery.” (One can also smell the money of the potential marketing opportunity of the corresponding fragrance). The woman, whom we have only known by her perfume, turns around. She is played by Todd Jr.’s stepmother, Elizabeth Taylor. The movie star, who had been married three times and was recent widowed, was twenty-seven years old and at the height of her beauty and fame. “I’m married to a girl who is a few years my junior,” Mike Todd had boasted. “As a matter of fact, she’s a few years my junior’s junior.”

The majority of the audience at the premiere were influential members of the film industry and press, and the atmosphere was full of anticipation as they prepared to sample the new, revolutionary experience alongside stars such as Elizabeth Taylor and Frank Sinatra. Todd advertised the film as shot in “Glorious Smell-O-Vision,” described as “the process to end all processes.” Cardiff himself was convinced he’d made a great movie. “Well, the magnificent machinery worked wonderfully,” he recalled in his memoir. “The only trouble was, the smells that were projected towards the eager nostrils were exactly like cheap eau-de-Cologne.” After its Chicago debut, the film played at the Warner Theatre in New York, which had also been expensively adapted, but the critics, in Cardiff’s description, “all had wrinkled noses and acerbic tongues.” “It stinks!” was just too tempting a headline. Apparently, as with Aromarama, the smells lingered in the cinema, adding to the sensory confusion, and Todd regretted that the pipes that pumped in the odors hadn’t also been used to vacuum the cinema clean before the release of the next one. However, by the time he had this epiphany, it was already too late.

Herb A. Lightman, writing in the February 1960 issue of American Cinematographer, described the film as “a knock-down-drag-out chase, adventure, who’s-gonna-do-it? mystery travelogue done in the Hitchcock manner—but not by Hitchcock.” Cardiff had worked with Hitchcock on Under Capricorn (1949), and in Scent of Mystery he channels the auteur, bringing to the film some wonderful, unexpected, vertiginous angles. But even without the smells, the meandering tale falls rather flat. Scent of Mystery’s thunder was stolen by Weiss’s Aromarama documentary, which had come out a month earlier, and, in what Cardiff describes as a “bathetic coup de grace,” a few days before the New York opening “an enterprising gent showed an awful ‘B’ film and installed incense in the air conditioning, triumphantly advertising his film as ‘the first smellie.’”

Cardiff later described the film as a “complete disaster,” “the one film I want to erase from my memory,” though he maintained that this was through no fault of his own: “It was a very interesting story with a marvelous photographic background of Spain, but the smell, for which it was made, didn’t exist.” Sons and Lovers (1960), for which he won a Golden Globe for best director and was nominated for an Academy award, came out the following year and he preferred to talk about that. In a 1986 interview, Cardiff blamed Laube for the failure, describing the professor as a “phony gentleman … a fake.” The “scent energizer” was a version of the machine being operated behind the curtain at the end of The Wizard of Oz. “I don’t know whether Michael Todd tried to sue him or not, or whether he just took it on the chin,” he said.

Todd Jr., looking back on his career, dismissed the film as “just a novelty gimmick.” He claimed that even if it had worked, an audience would have only been intrigued by one or two more Smell-O-Vision films. He released the film, without a smell track, as Holiday in Spain, but it did little business and the smellies were consigned to an afterlife in theme parks; cinemas reverted to their usual stench of stale popcorn, cigarettes, and hotdogs. For a decade, the Cinestage in Chicago was used to show adult films and, when the city bought it from Elizabeth Taylor in the 1980s, gutting it to make way for a new theater complex, the “smell brain” was still lingering in the basement. As for Laube, according to his daughter: “Scent of Mystery was his swan song. He lost all his money, my mom went to work, and he died about 16 years later, penniless and broken.”

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet and Keeper of Design, Architecture, and Digital at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.