The Floating Island

HMS Habbakuk and the icy promise of pykrete

Paul Collins

In late 1942, Lord Louis Mountbatten—the British military’s Chief of Combined Operations—paid a visit to Winston Churchill at his official country home, Chequers. Mountbatten had with him a small parcel of great importance. A member of Churchill’s staff apologized that the Prime Minister was at that moment in his bath.

“Good,” said Mountbatten as he bounded up the stairs. “That’s exactly where I want him to be.” Mountbatten entered the steaming bathroom to find Churchill in the tub. It was generally not a wise thing to interrupt Sir Winston in his bathtub.

“I have,” Mountbatten explained, “a block of a new material that I would like to put in your bath.”

Mountbatten opened his parcel and dropped its contents between the Prime Minister’s bare legs in the water. It was a chunk of ice.

Rather than bellow at his Chief of Combined Operations, Churchill stared at the ice intently—and so, standing by the bathtub, did Mountbatten himself. Minutes passed, and still they looked into the steaming depths of bath water before them. The ice was not melting.[1]

Ice is strange stuff: brittle when struck suddenly, yet malleable when pressured over a period of time. With low but steady pressure, this plastic deformation can continue indefinitely. Above all, ice is unpredictable. Molded into a beam, it will fracture at loads anywhere from five kilograms per square centimeter to thirty-five kilograms per square centimeter. Because it fails at unpredictable loads, it is not ideal as a building material. But what was bobbing about in Churchill’s bathtub was no ordinary ice: it was pykrete.

Pykrete is a super-ice, strengthened tremendously by mixing in wood pulp as it freezes. By freezing a slurry of 14 percent wood pulp, the mechanical strength of ice rockets up to a fairly consistent seventy kilograms per square centimeter. A 7.69 mm rifle bullet, when fired into pure ice, will penetrate to a depth of about thirty-six centimeters. Fired into pykrete, it will penetrate less than half as far—about the same distance as a bullet fired into brickwork. Yet you can mold pykrete into blocks from the simplest materials and then plane it, just like wood. And it has tremendous crush resistance: a one-inch column of the stuff will support an automobile. Moreover, it takes much longer to melt than pure ice. But as strong and eco-friendly as it is, pykrete remains forgotten today save among glaciologists, who express bafflement over why no one has made use of it. “I don’t really know why it has languished in obscurity,” admits Professor Erland Schulson, director of the Ice Research Laboratory at Dartmouth College.[2]

Pykrete is the namesake of Geoffrey Pyke, who the Times of London once declared “one of the most original if unrecognized figures of the present century.” His career began in 1914 when, as a teenager at Cambridge University, he landed a foreign correspondent job by using a false passport to sneak into wartime Germany. After getting tossed into a concentration camp, he fled the country in a daring daytime escape. In the 1920s, he virtually created progressive elementary education in Great Britain, all for the sake of his own son’s education. Pyke financed his own school by brilliantly riding futures markets and controlling a quarter of the world’s supply of tin, a ploy which brought him to financial ruin in 1929. He lived on as an eccentric hermit, publishing prescient warnings of Nazism and proposing one of the first media watchdogs. After the war, his freelance genius helped propel the creation of the National Health Service.[3]

During the war, he appeared at the office of the Chief of Combined Operations with a simple recommendation for his hiring. “You need me on your staff,” the shabbily dressed man explained to Lord Mountbatten, “because I’m a man who thinks.” What Pyke was thinking about just then was building ships out of ice.

Pyke envisioned ships as vast and solid as icebergs. You could make the sides of your boat tens of feet thick, hundreds if you felt like it, and bullets or torpedoes would bounce away or knock off pathetically ineffectual chunks. And when a torpedo did knock a chunk away—so? You were floating in a sea of raw repair material. Given how long it took pykrete to melt, and the minimal onboard refrigeration equipment needed to stay frozen and afloat, it would be months or years before the boats exhausted their usefulness. In battle, the ice ships could put their onboard refrigeration systems to good use by spraying super-cooled water at enemy ships, icing their hatches shut, clogging their guns, and freezing hapless sailors to death.

Pykrete freighters could carry eight entire Liberty class freighters as cargo, but Pyke’s dream was not to use them as cargo ships but as aircraft carriers. One of the great disadvantages of aircraft carriers had always been that their short landing surfaces and cramped storage favored small planes with foldable wings and light armor. The most desirable fighters, like Spitfires, were not an easy fit for carriers, and bombers were altogether out of the question. Pyke’s logical conclusion was to build a behemoth: the HMS Habbakuk, he called it. Constructed from forty-foot blocks of ice, his Habbakuk would be two thousand feet long, three hundred feet wide, with walls forty feet thick. Its interior would easily accommodate two hundred Spitfires. The largest ship then afloat was the HMS Queen Mary, which weighed in at eighty-six thousand tons. The Habbakuk would weigh two million tons.[4]

For a man who had had ice thrown into his bath, Winston Churchill was surprisingly receptive to the idea. After reading the formal War Cabinet report on the Habbakuk project, Churchill shot back a memo stamped “Most Secret” the next day, on 7 December 1942. “I attach the greatest importance to the prompt examination of these ideas,” he wrote. “The advantages of a floating island or islands, even if only used as refueling depots for aircraft, are so dazzling that they do not need at the moment to be discussed.”

Mountbatten had already ordered Pyke and his colleague Martin Perutz to produce pykrete in large quantities to test and perfect it. Utmost secrecy was required, so Pyke set up shop in a refrigerated meat locker in a Smithfield Market butcher’s basement; his “shop assistants” were disguised British commandos. Their work was carried on behind a protective screen of massive frozen animal carcasses. When Mountbatten came to visit the operation, it was so hush-hush that Lord Louis had to disguise himself as, of all things, a civilian.

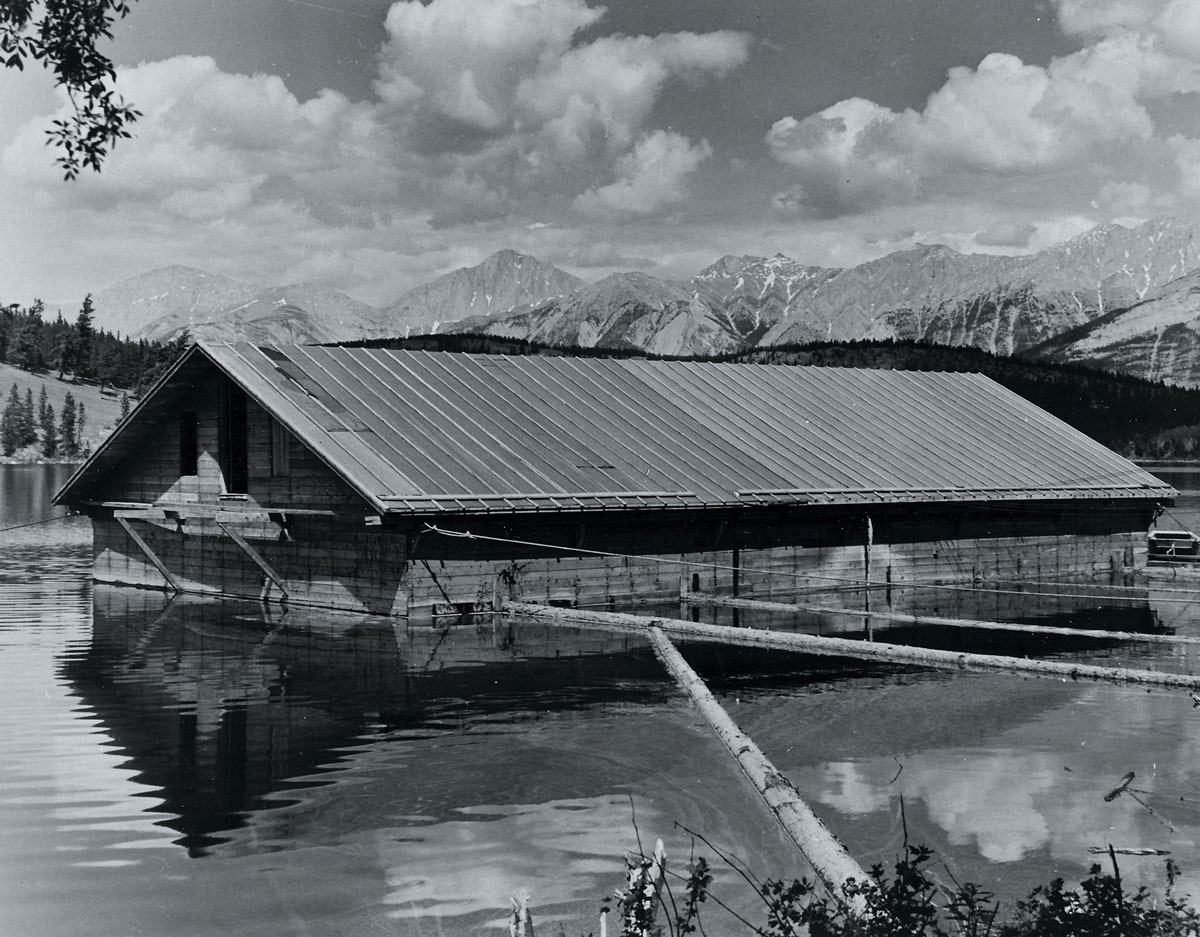

It looked like an ordinary boathouse, tucked in on the shore of Patricia Lake, just outside Jasper, Ontario. But it was not a house at all—it was the boat, with a tin roof stuck on top to make the bizarre craft look like a boathouse.

The prototype Habbakuk was sixty feet long and thirty feet wide, weighing in at a thousand tons, and was kept frozen by a 1-horsepower motor. The boat would not move very quickly, and the enemy would hardly fail to see it coming, but this hardly mattered. “Surprise,” Pyke theorized in his first Habbakuk memo, “can be obtained from permanence as well as suddenness.” The immense hull was just as strong as Pyke had predicted, but Mountbatten eschewed the scientist’s reports for a more direct testing method: hauling out a shotgun and trying to blow a hole into their precious prototype’s side. He failed.

Meanwhile, the butcher’s backroom had produced enough samples for Mountbatten and Churchill to take their pykrete show on the road. Mountbatten unveiled the invention at a tense secret meeting of the Allied chiefs of staff at Quebec’s Chateau Frontenac Hotel in August 1943. With the heads of nearly every Allied branch in attendance, the outside of the conference room was filled with high-level staff waiting to give their reports. British Air Marshall Sir William Welch was among them when they heard two pistol shots ring out from inside the conference room.

“My god,” Welch yelled, “the Americans are shooting the British!” Guards rushing into the conference room found Lord Mountbatten holding a pistol amidst a scene of shattered ice and mayhem. And yet some of the officers were laughing. There was a very reasonable explanation for it all. Mountbatten had set out two blocks of material and then pulled out a gun to give the assembled chiefs a little demonstration. The first shot had been at a block of pure ice, which shattered. Nobody was much surprised by this. But the second shot proved very surprising indeed. This time, Mountbatten shot a piece of pykrete, and the bullet ricocheted right off the block and zipped across the trouser leg of Fleet Admiral Ernest King. It was quickly decided that Mountbatten had made his point.[5]

Churchill and Roosevelt soon came to an agreement that the world’s biggest ship should be built. But one man was conspicuously missing from these meetings: Pyke. The ship’s inventor was stunned to discover that to appease the Americans—who were not too keen on pottering eccentrics—he had been cut loose from his own project. It hadn’t helped that Pyke had sent a cable marked “Hush Most Secret” back to Mountbatten. It read, in its entirety: “CHIEF OF NAVAL CONSTRUCTION IS AN OLD WOMAN. SIGNED PYKE.”[6]

In the end, the Habbakuk was never built anyway. Land-based aircraft were attaining longer ranges, U-boats were being hunted down faster than they could be built, and the US was gaining numerous island footholds in the Pacific—all contributing to a reduced need for a vast, floating airfield. And deep within the newly built Pentagon was the knowledge that America already had a secret weapon in development to be used against Japan—an end to the war that would be brought about not by ice but by fire.

The prototype ice-ship, abandoned in Patricia Lake, did not melt until the end of the next summer.

- This Chequers account is included in the only biography of inventor Geoffrey Pyke: David Lampe’s wonderful 1959 book Pyke, the Unknown Genius (London: Evans Brothers, 1959).

- Martin Perutz, “Description of the Iceberg Aircraft Carrier and the Bearing of the Mechanical Properties of Frozen Wood Pulp Upon Some Problems of Glacier Flow,” in Journal of Glaciology, March 1948, pp. 95–104. There’s an entertaining modern experiment involving shooting pykrete at <goo.gl/JHx7F>. Accessed 30 July 2012. The Schulson quote is from my 7 March 2001 email interview with him.

- See Pyke obituaries “The Fearless Innovator,” The Times, 26 Feb 1948, p. 6; and “Everybody’s Conscience,” Time, 8 March 1948, pp. 31–33.

- Due to an Admiralty clerk’s error, it was “Habbakuk” rather than the correct biblical name “Habakkuk.” Pyke’s memos are available through the National Archives; they are Admiralty files ADM 1/15672 and ADM 1/15677. Also see the London Illustrated News, 2 March 1946, pp. 234–237.

- “War on Ice,” Newsweek, 11 March 1946, p. 51.

- Martin Perutz, “Enemy Alien,” The New Yorker, 12 August 1985, pp. 35–54. Perutz notes that design flaws might have made the Habbakuk impossible anyway.

Paul Collins edits the Collins Library for McSweeney’s Books and is the author of Banvard’s Folly (Picador, 2001) and the forthcoming travelogue-memoir Sixpence House (Bloomsbury USA). He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.