Leftovers / At Death’s Doorknob

The bloody-minded invention of Dr. Dibble

Paul Collins

“Leftovers” is a column that investigates the cultural significance of detritus.

Disposing of very large quantities of blood is an onerous chore. You can’t give the stuff away—well, perhaps you can, but few are willing to endure the stares that proving this point entails.

Yet the slaughtering and butchering trade has long faced precisely this dilemma. London butchers in Newport Market during the 19th century were banned from tipping blood into the street sewers, due to the rats it attracted, though enough of them flouted this law that sewers under meat markets became commonly known as “blood sewers.” Among London sewer workers, toiling in these “blood lines” vied in unpleasantness with the caustic rivers that ran under soapmakers and the boiling drains beneath sugar refineries. Indeed, one of the better ways for meat merchants to dispose of cattle blood was by selling it to these sugar mills, which used it in their refining process.[1]

Recycling was already the order of the day: bones were ground up for phosphorus matches, tobacco ash was turned into tooth-cleanser, old wool sweaters shredded into wallpaper flocking, and it was discovered that desiccated fish eyes made delightful buds for artificial flowers. Unlucky stray dogs wound up as phony cod-liver oil, and tallow makers in Paris were not above fishing dead dogs and cats out of the Seine when production quotas demanded it. But blood and animal waste remained a perennial problem. New Yorkers found one promising use for it in the 1870s: they tried mixing blood with other discarded offal to manure their fields.[2]

But perhaps the most creative approach to blood disposal is one we might all still readily grasp, as this headline from the January 1892 issue of Manufacturer and Builder magazine attests:

Door Knobs, etc., from Blood and Sawdust.

Doctor W.H. Dibble, of New Jersey, had patented an exciting material for interior decorators: hemacite, he called it. Hemacite, the magazine explained, was “nothing less than the blood of slaughtered cattle and sawdust, combined with chemical compounds, under hydraulic pressure of forty thousand pounds to the square inch.”

Sawdust back then had already found use in papermaking and as a filling for dolls, and desperate Swedes had also figured out how to distill brandy from it. But these base ingredients of blood and sawdust remained plentiful, and were wonderfully effective when combined together as an animal polymer, the blood’s albumen binding with the wood particulate. “Hemacite,” noted the magazine, “is susceptible of a high polish, is impervious to heat, moisture, atmospherical changes, and, in fact, is practically indestructible.” Starting out as brownish powder resembling snuff, hemacite could be molded into any shape and dyed to any color, and it became a popular and reasonably priced substitute for both wood and metal among architect and decorators.

In fact, by the time of the Manufacturer and Builder article, the Trenton headquarters of the Dibble Manufacturing Company had been for some years producing hemacite house trimmings and drawer pulls, and it now had a catalogue of hundreds of designs of their most popular product, hemacite doorknobs. The doorknobs carried a guarantee for the lifetime of the door, because rather than having a separate knob and shaft to wear out, they were molded as one unbreakable piece. It was a successful enough product that Dibble eliminated his own name from the enterprise entirely: Trenton became the proud home of the Hemacite Manufacturing Company.

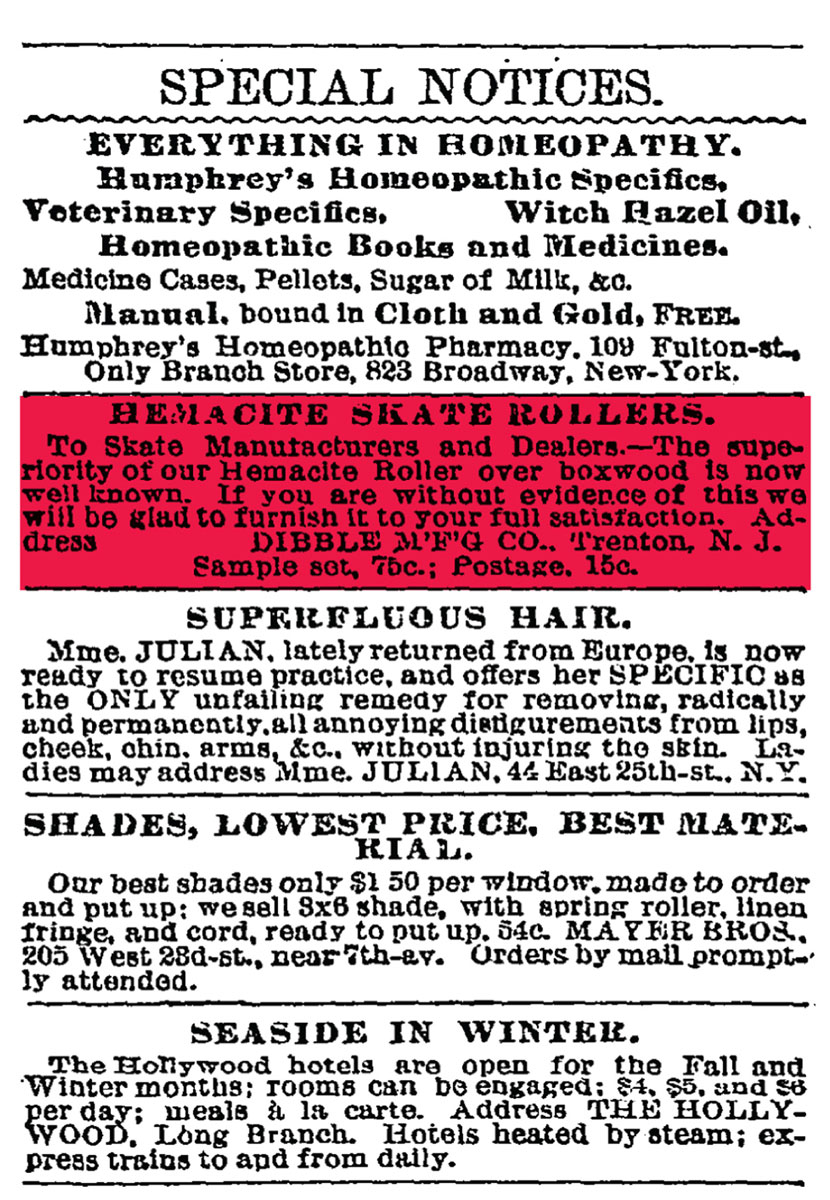

Dibble branched out into products like hemacite cash register buttons and, quick to pick up on the latest fads, roller skates.[3] “To skate manufacturers and dealers,” boasted an ad in the 11 October 1885 issue of the New York Times, “the superiority of our Hemacite Roller over boxwood is now well known.” The campaign seems to have worked: the 21 February 1903 Times carries an ad by the Siegel Cooper department store, hawking athletic supplies, and nestled among promotions for medicine balls and $12 Swedish Dogskin Coats (“For sporting use or driving”) is an entry for 75-cent roller skates with hemacite wheels, a more expensive option than skates with plain “black wheels.” Curiously, Siegel Cooper’s ad appears over a plug for Plasmon Cocoa mix—“A blood-invigorating and muscle-making beverage of the highest order.” Plasmon’s active invigorating ingredient? Albumen, which was also the organic binding agent behind hemacite roller skate wheels.

W.H. Dibble was certainly an inventive fellow, having previously patented a dentist’s contraption to simultaneously pry patients’ mouths open while draining away their saliva, but his hemacite products were not quite the amazing innovation that he led others to believe.[4] Like a true American, what he had really done was nick a foreign idea and improve upon it. Long before Dibble’s 1877 application, the Parisian writer Francois Lepage secured an 1855 patent for what he called bois durci: a pressurized mixture of sawdust and cattle blood or, less economically, egg whites. Lepage founded the Bois Durci Company and exhibited its wares at the Great International Exhibition of 1862, back when Dibble was still tinkering with ways to suck the spit out of dental patients. Bois durci went on to turn up in a variety of 19th century inkstands, plaques, picture frames, and furniture; Edison even used it for the housing on early telephones.[5] Even bois durci was not the first use of blood in buildings. Cattle blood had long been used in “blood cements,” as, for that matter, had albumen from eggs, milk, and cheese. One Chinese recipe called for 100 parts slaked lime, 75 parts bullocks’ blood, and 2 parts alum. Floors in South Africa gained a black marble-like polish with the use of blood, and an early London tennis court acquired its hard and glossy surface in the same way; it has even been used as an additive in roofing material.[6] It seems there is no part of a house that cannot be manufactured, in part, from blood. Hemacite certainly captured the attention of Victorian architects. By the turn of the century, though, Dibble’s firm had already suffered a factory fire, moved shop to a new building, and changed its name to Trenton Brass and Machine Company. The old Hemacite Company was as much a victim of changing times as fire: new plastics like Bakelite were in the offing, pushing aside the quaint notion of sawdust mixed with blood. The rechristened company soldiered on for many more decades, surviving the Depression and a postwar strike, and until recently still supplied fittings to plumbing contractors. But even Trenton Brass is gone now, and with it the last faint trace of Dr. W.H. Dibble and his Hemacite Company.[7] But old hemacite house fixtures, strong and durable as they are, live on. So the next time you find yourself running short on bouillon, you may take this token of advice: consider boiling your doorknobs.

- The varieties of London sewers are from John Hollingshead’s splendid subterranean travelogue, Underground London (1862).

- Recycling methods are from “The Art of Utilizing,” in Manufacturer and Builder, October 1871. Blood-manure and sawdust-brandy are described in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, January 1874, p. 304.

- An unpaid bill owed to Hemacite by the August Cash Register Company is cited in the “Business Troubles” column of the New York Times for 14 February 1894.

- See “Dibble’s Dental Apparatus” in Scientific American, 30 September 1865.

- A description of Bois Durci is available at the Plastics Historical Society’s webpage: www.plastiquarian.com.

- See “Blood Used in Building,” in Notes and Queries, series 10 no. 2 (1905), pp. 34–35, and no. 3, p. 373.

- See Edwin Robert Walker et al., The History of Trenton, 1679–1929 (Princeton: Princeton University Press and the Trenton Historical Society, 1929). Gary Nigh of the Trenton Historical Society provided valuable information on the company’s history. The strike is detailed in the 16 March 1946 New York Times.

Paul Collins is the author of Banvard’s Folly and the forthcoming Sixpence House: Lost in a Town of Books (Bloomsbury). He edits the Collins Library for McSweeney’s Books.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.