Breaking Bread

The dark and white flours of ideology

Nicolaia Rips

I was on the phone with my father, chatting about Berlin, when he asked me a question that I had not reflected on—though a subject dear to my heart.

“How is the food?”

I realized I hadn’t truly had any German food. I lived in a predominantly Turkish neighborhood of Neukölln, and ate Turkish, Thai, Syrian, and Italian food—everything but German. Traditional German food was scarce, though German bread was plentiful. Language reflects this—the direct translation of Abendbrot (dinner) is “evening bread” and Brotzeit (snack) is “bread time.” A play on Brotzeit, Zeit für Brot is the name of a popular bakery chain. The bread register maintained by the German Institute for Bread, located in Weinheim in the southwest of Germany, declares that there are now more than three thousand officially recognized types of bread in the country.[1]

Bertolt Brecht writes in his diary in 1941 on the topic: “There is no proper bread in the states and I like my bread. My main meal in the evening is bread and butter.”[2] The deficiency of adequate bread is a main complaint of many Germans living abroad. Unlike its southern neighbors France or Italy, with their airy ciabattas, focaccias, and baguettes, Germany has a climate less accommodating to growing wheat flour, instead relying on toothsome sourdoughs made with spelt or rye and filled with grains, nuts, and seeds.

Bread evokes memories of sharing a meal with loved ones during peacetime and of hunger satiated, a distant feeling for a nation attempting to rebuild from the defeat of World War I, the economic severities of the 1920s and 30s, and the political turmoil of the Weimer Republic. During World War II, the Nazi party exploited the comfort that bread provided. In its daily bulletin of 15 October 1941, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency informed its readers that in addition to the recession and the killing of Christ, the Jews were now also being blamed by the Germans for the creation of white bread. “The baking of white bread,” a Nazi broadcaster quoted by the agency had explained, “was promoted by Jews both for speculative reasons and also for the purpose of undermining the health of the German people. Before the Jews settled in Germany, the people generally ate whole wheat bread. For the last century, however, the Jews pushing themselves in between the producer and the consumer, fostered the production of ‘dead flour’ which is deprived of the main nutritive value.”[3] This was a particularly insidious piece of propaganda because of the psychological values that bread connotes. Blaming the Jews for creating white bread—weak stuff cropping up in bakeries and grocery stores across the Germany—set them in diametric opposition to traditional values.

Because of its central role in human nutrition, bread has appeared in countless cultural and religious keystones: the epic of Gilgamesh; the description of Egypt as the land of bread-eaters; Jewish oppression and the feast of Passover (bread of the afflicted); the Roman cry of “bread and circuses”; bread as a symbol in the poetry of Omar Khayyam; bread that signifies the body of Christ in the Eucharist.[4] In short, made with simple, wholesome ingredients, bread is the staff of life. German bread continues to exemplify this tradition, one that Jews were supposedly destroying with processed white bread.

In contrast to the German disdain for white bread, in the United States it had become a symbol of successful industrialization, of a promising modern future. In the early twentieth century, Americans had developed a new anxiety about the potential contamination of their food supply. Eugene Christian and Mollie Griswold Christian exemplify the dramatic phobias surrounding both home-baked and bakery-bought bread in their 1904 book Uncooked Foods and How to Use Them: A Treatise on How to Get the Highest Form of Animal Energy from Food, with Recipes for Preparation, Healthful Combinations and Menus. They write, “Bread rises when infected with the yeast germ, because millions of these little worms have been born and have died, and from their dead and decaying bodies there rises a gas just as it does from the dead body of a hog.”[5] Yum! Mass-produced bread seemed somehow safer, more sterile, in the public eye.

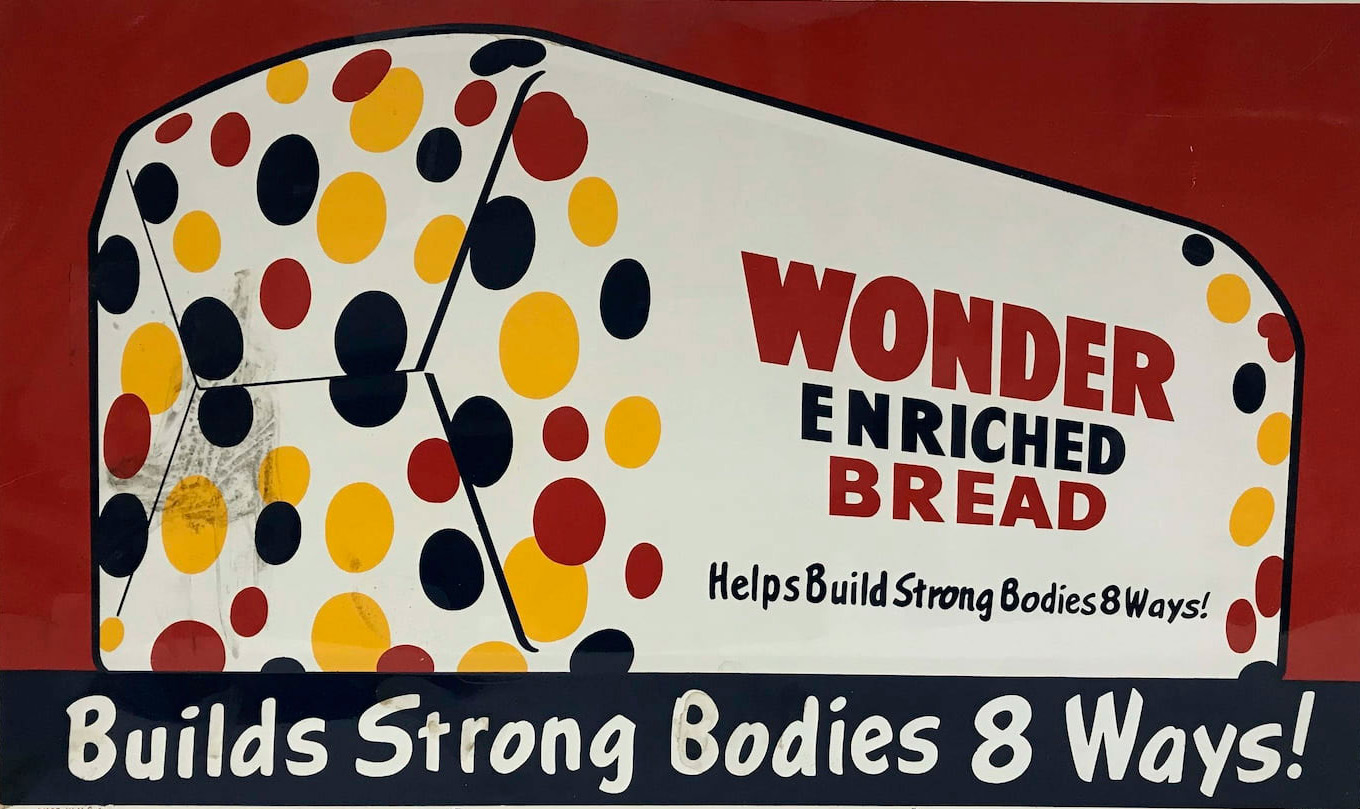

Wonder Bread, created in 1921, was the gold standard; glowingly white, luxuriantly soft, nutrition-less (it was only fortified years later), barely bread. Its popularity and eventual rise to cultural icon has as much to do with the American zeitgeist as its taste. As an article on the Smithsonian website memorializing Wonder Bread notes, “The new Wonder Bread didn’t suggest hearth and home. On the contrary, the unnaturally vibrant colors of the logo and visual purity of this new, virgin white, 1.5-pound loaf perfectly evoked the otherworldliness of the enormous manufacturing system that was seen as America’s future.”[6] Where German bread meant a return to the past, later to be figured as a mythological past where Aryans reigned, Americans fought for a white bread of an industrialized future.

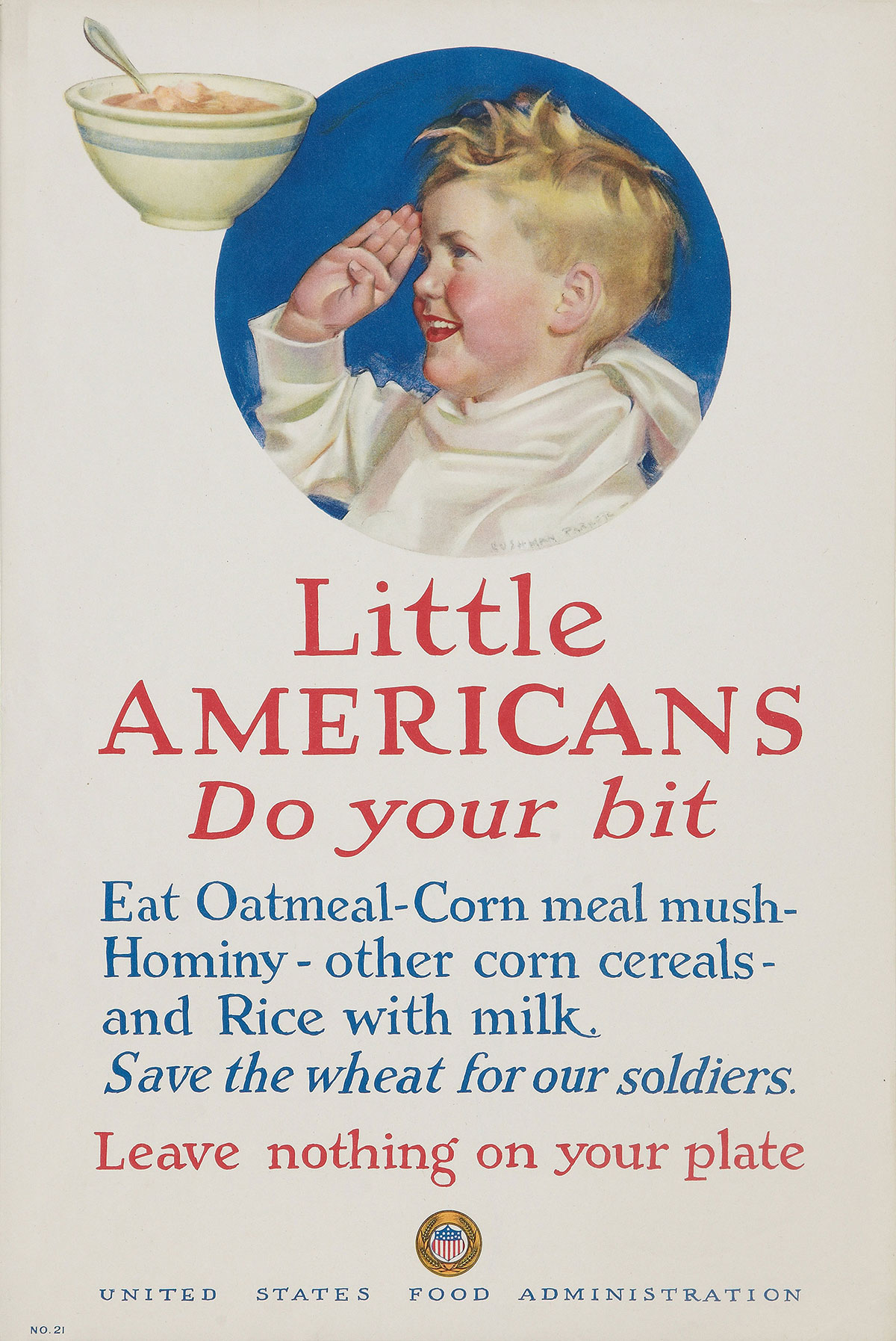

The precedent for white bread as a patriotic symbol was in fact set during World War I. Because of the US’s ample food supply, it provisioned England, France, Belgium, and other nations, which were incapable of providing the five thousand calories a day that American soldiers were consuming. To ease the burden of buying and shipping massive amounts of wheat, the US Food Administration fixed the commodity’s price. At the same time, Woodrow Wilson created the Committee on Public Information (CPI), an agency that churned out propaganda, some of which encouraged abstemiousness and the swapping out of certain ingredients for more frugal options. One US Food Administration poster announced: “Save the wheat for our soldiers.”

In his 1948 article entitled “Bread or Freedom?”, historian F. Edward Lund offers an interesting take on the politicization of bread: “The electioneering promise of bread to the poor—‘Pass the biscuits, pappy’—and of property to the rich—‘lower taxes’—is repeatedly successful, particularly if, in return for their votes, the political candidate will also promise to protect each group from the other.”[7] Lund’s argument is that at the most basic level, totalitarianism is bread in exchange for freedom. When bread is discussed in totalitarian regimes, it’s not simply bread but bread as a gastropolitical contract: giving up that which defines you as a human being (free will) for that which sustains you (food).[8] The state guarantees sustenance in exchange for compliance.

If the totalitarian promise of bread offers security at the expense of freedom, then what of democratic bread? When the US government asked citizens to give up wheat at home in order to make it available for the troops, it was not urging people to fight for bread. Instead, it asked them to sacrifice part of their diet in order to fight for ideology. Give up bread for freedom.

Bread as a symbol of material and physical fulfillment was also invoked in the US suffrage movement, but there the opposition between bread and freedom was dismissed as a false choice. A rallying cry of suffragists was “Bread and Roses,” a slogan coined by Helen Todd in the early 1910s for speeches that she would give while traveling through Illinois advocating for women’s rights. In an essay published in The American Magazine in September 1911, Todd, a factory inspector, further explained the phrase, adding that women’s suffrage “will go toward helping forward the time when life’s Bread, which is home, shelter and security, and the Roses of life, music, education, nature and books, shall be the heritage of every child that is born in the country, in the government of which she has a voice.”[9] Simply put, Todd acknowledges that while bread may be the staff of life, freedom and the pleasures it entails are just as critical.

And how do I like my bread? I prefer it sliced thick and slathered with butter, and as free as possible of political symbolism. But even that, sadly, cannot be, as it turns out that I am gluten- and lactose-intolerant.

- English-language homepage of the German National Bakers Academy. Available at https://www.akademie-weinheim.de/international/english/.

- Bertolt Brecht, Journals 1934–1955, ed. John Willett, trans. Hugh Rorrison(New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 1993), p. 161. Lack of capitalization in original.

- “White Bread Is a “Jewish Invention” Nazi Radio Explains to Undernourished Germans,” JTA Daily News Bulletin, vol. 8, no. 253 (15 October 1941), p. 3. Available at jta.org/1941/10/15/archive/white-bread-is-a-jewish-invention-nazi-radio-explains-to-undernourished-germans.

- See Louise O. Fresco, “Bread: The Most Iconic of Foods,” in Hamburgers in Paradise: The Stories behind the Food We Eat (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

- Eugene Christian and Mollie Griswold Christian, Uncooked Foods and How to Use Them: A Treatise on How to Get the Highest Form of Animal Energy from Food, with Recipes for Preparation, Healthful Combinations and Menus (New York: The Health-Culture Company, 1904), p. 105. This book is credited with pioneering the raw food diet.

- Sam Dwyer, quoted in Colin Schultz, “The Life And Death of Wonder Bread,” Smithsonian.com (16 November 2012). Available at smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/the-life-and-death-of-wonder-bread-129979401.

- F. Edward Lund, “Bread or Freedom?” Peabody Journal of Education, vol. 25, no. 4 (January 1948), p. 144.

- Michaela DeSoucey coined the term gastropolitics in her book Contested Tastes: Foie Gras and the Politics of Food (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), p. xii.

- Helen Todd, “Getting Out the Vote: An Account Of a Week’s Automobile Campaign by Women Suffragists,” The American Magazine, vol. 72, no. 5 (September 1911), p. 619. The phrase “Bread and Roses” was subsequently adopted by James Oppenheim for his poem of the same name, published in the December 1911 issue of The American Magazine.

Nicolaia Rips is a writer based in Providence, Rhode Island. Her works include the memoir Trying to Float (Scribner, 2016), The Irregular Report: Gen Z and Fluidity (Gucci, 2019), and the film As They Slept (Neon Heart Studios, forthcoming).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.