Out of the Picture

Maurice Blanchot and the refusal of photography

Louis Kaplan

He is dead and therefore he is not himself anymore. But then again, he would say that he was never “he” when he was alive because he had given himself over to the impersonal, the neuter, the neutral voice of writing, and the space of literature where he died before his time, and where he lives on for others like myself to write on his remains, to write after him.

After is the word that I am after—when I write in the wake of Maurice Blanchot, when I write on what remains of Maurice Blanchot. After is a word that appears when he writes about the two versions of the imaginary. Do you remember? The image arrives after—always belated, always delayed, always looking into the mirror and remembering that it is an image, that it is an afterimage.

After all, he wrote about “after” this way: “After the object comes the image. ‘After’ means that the thing must first take itself off a ways in order to be grasped.”

This takeoff is also the step back that makes room for memory, for reflection, for the conjuring of the image, for photography.

But now I have said the word and named the thing to which he had such an aversion. Is he rolling over in his grave? Can he bear the thought of what would reanimate him as an image? Photography is the medium to which he did not lend himself, to which he did not take, to which he did not expose himself. The camera is the technical apparatus that he did not care to smile into. Maurice Blanchot was a camera-shy guy.

So what to say about these two photographs that have survived him? The older one when he was a young man and the newer one when he was an old man.

The first image of Blanchot is to be placed among the countless snapshots of everyday life that are taken and passed around among friends and that serve as mementos of the space-time they have shared. The image features Blanchot as a man in his twenties in dandyish attire seated on a car and surrounded by companions. The dark-haired man is none other than Blanchot’s lifelong friend, the philosopher of alterity, Emmanuel Lévinas. As far as the facts go, the group is on their way to Charles Blondel’s home for a dinner party in Strasbourg. It is as if Blanchot in his exposure to the camera and in his being posed in exteriority has yielded to the etiquette required by the ethical philosopher who believed so strongly in faciality—in the indebtedness of the face as it turns itself toward the Other.

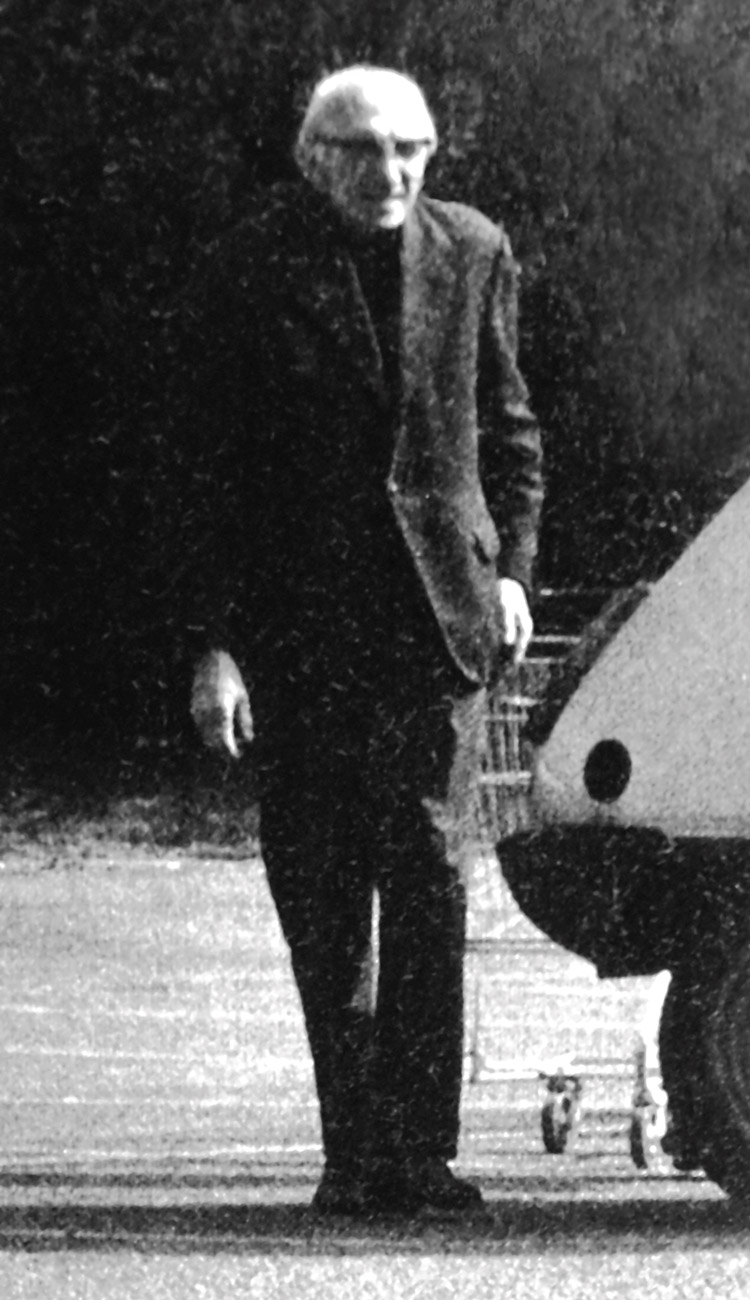

The more recent image has the word paparazzi written all over it. Amusing to think about the author of Thomas the Obscure as subject to such a celebrity treatment! The image shows a lanky old man dressed in black with white hair and glasses walking in the parking lot of a supermarket with an empty shopping wagon behind him and the rear end of a white Renault car to his side (as if to balance the earlier photograph). It is a beautifully mundane environment to catch such a serious literary recluse and the grimace around his lips speaks volumes. Or am I just imagining that this is his expression for he may have been caught so unexpectedly that he did not have time to react negatively to this pesky surveillance camera?

Here is the young Blanchot willingly obliging friendship in the first snapshot image, and here is the old Blanchot in the other one resisting his arrest in the image that invades his desire for visual anonymity and the living death of the author.

In facing the dead Blanchot and conducting this autopsy in search for clues that somehow explain this refusal of photography, one turns to the first-person narrator of Blanchot’s Death Sentence (1948). While the English translation captures the interplay between mortality and writing, it will never pick up the arrest and the standard stoppage of time delivered in the French title L’Arrêt de mort. It underscores for us what photography shares with death. The photograph as proof has been placed under siege. It has been put into quotation marks at the very thought of an unmarked way of living. This cryptic text reads as follows:

I have kept “living” proof of these events. But without me, this proof can prove nothing, and I hope no one will go near it in my lifetime. Once I am dead, it will represent only the shell of an enigma, and I hope those who love me will have the courage to destroy it, without trying to learn what it means. I will give more details about this later. If these details are not there, I beg them not to plunge unexpectedly into my few secrets, or read my letters if any are found, or look at my photographs if any turn up, or above all open what is closed; I ask them to destroy everything without knowing what they are destroying.

On the one hand, the impersonal “I” of this text (whom I dare not call Maurice Blanchot) speaks to me of my betrayal of the secret as I am caught in the act of looking at and thinking about these few photographs that have turned up in the refuse. Why couldn’t I refrain from commenting on them and respect the enigma? But wasn’t it you who manufactured this mystique and who laid this trap in the first place with your hatred of photography so that you set up your photographic image—in its scant presence and in its overwhelming absence—into an even greater object of fascination?

Or could it be that through this refusal of the photographic image you are somehow remaining “truer” to its meaning in marking how the photograph or any image is based on absence and somehow superfluous even when it is right before our eyes and staring us in the face? There would be no need for Maurice Blanchot to bother with accumulating images of himself if these are but the shell of an enigma based on an absent core of death, disappearance, and nothingness.

At the opening of “The Two Versions of the Imaginary,” he asks: “But what is the image? When there is nothing, the image finds in this nothing its necessary condition, but there it disappears.”

Louis Kaplan is Associate Professor of History and Theory of Photography and New Media at the University of Toronto, and Director of the Institute of Communication and Culture at the University of Toronto at Mississauga. He is the author of American Exposures: Photography and Community in the Twentieth Century (University of Minnesota Press, 2005) and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy: Biographical Writings (Duke University Press, 1995), among other writings.