Geographical Amusement

The rise of the cartographic board game

Colton Valentine

In 1795, Henry Carington Bowles released Bowles’s European Geographical Amusement, or Game of Geography, the latest in his family’s board game series. Allegedly based on a 1749 travelogue, “the Grand Tour of Europe, by Dr. Nugent,” it combined learned pretensions with simple rules. “Having agreed to make an elegant and instructive TOUR of EUROPE,” players took turns rolling an eight-sided “Totum” and moving their “Pillars” through the appropriate number of cities. Whoever returned to London first was “entitled to the applause of the company and honor of being esteemed the best instructed and speediest traveler”: an enviable but deceptive accolade. In fact, erudition and swiftness were inversely correlated in Bowles’s game; being “instructed” required that your Pillar be delayed.

An opening roll of five, for instance, landed you in Blois, “a pleasant town upon the Loire,” where you would “stay two turns, and learn to speak the French language in its purity,” while a six on the next, for a cumulative eleven, fixed you briefly in Bordeaux to regale yourself with good claret. Other sojourns were less desirable. On forty-one, you found Ferrara, “once a flourishing city, but greatly on the decline, since it became subject to the pope” and learned that “this being so unfortunate a place, the traveler must turn back to 7. St. Malo.” That route made little navigational sense, but it exemplified the game’s ardent anti-Catholicism. Rome, in fact, was judged “once mistress of the world, but now only capital of the Pope’s dominions,” so you needed two turns “to view its curiosities, and reflect on the abuses of papal government.” It’s no wonder the Anglican Pillars raced back to London, taking an approach Gustave Flaubert would memorialize in his Dictionnaire des idées reçues: “VOYAGE—Doit être fait rapidement.”[1]

Of course, no one was voyaging particularly rapidly in 1795. Steam ships and railways were decades away, leaving the glamour of the Grand Tour accessible only to those, like Dr. Nugent, who could afford a network of costly coaches.[2] At the century’s end, even the elite were homebound, as the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars functionally sealed the continent off to Brits. While our recent penchant for analogizing pandemics to martial crises is pernicious in many ways, they do have one thing in common: borders close.

So like COVID-19-ers, late Georgians went on virtual tours. Without live feeds of Shibuya Crossing or the aurora borealis, they made do with travel writings and maps—plus a new product that synthesized the two: the cartographic board game.[3]

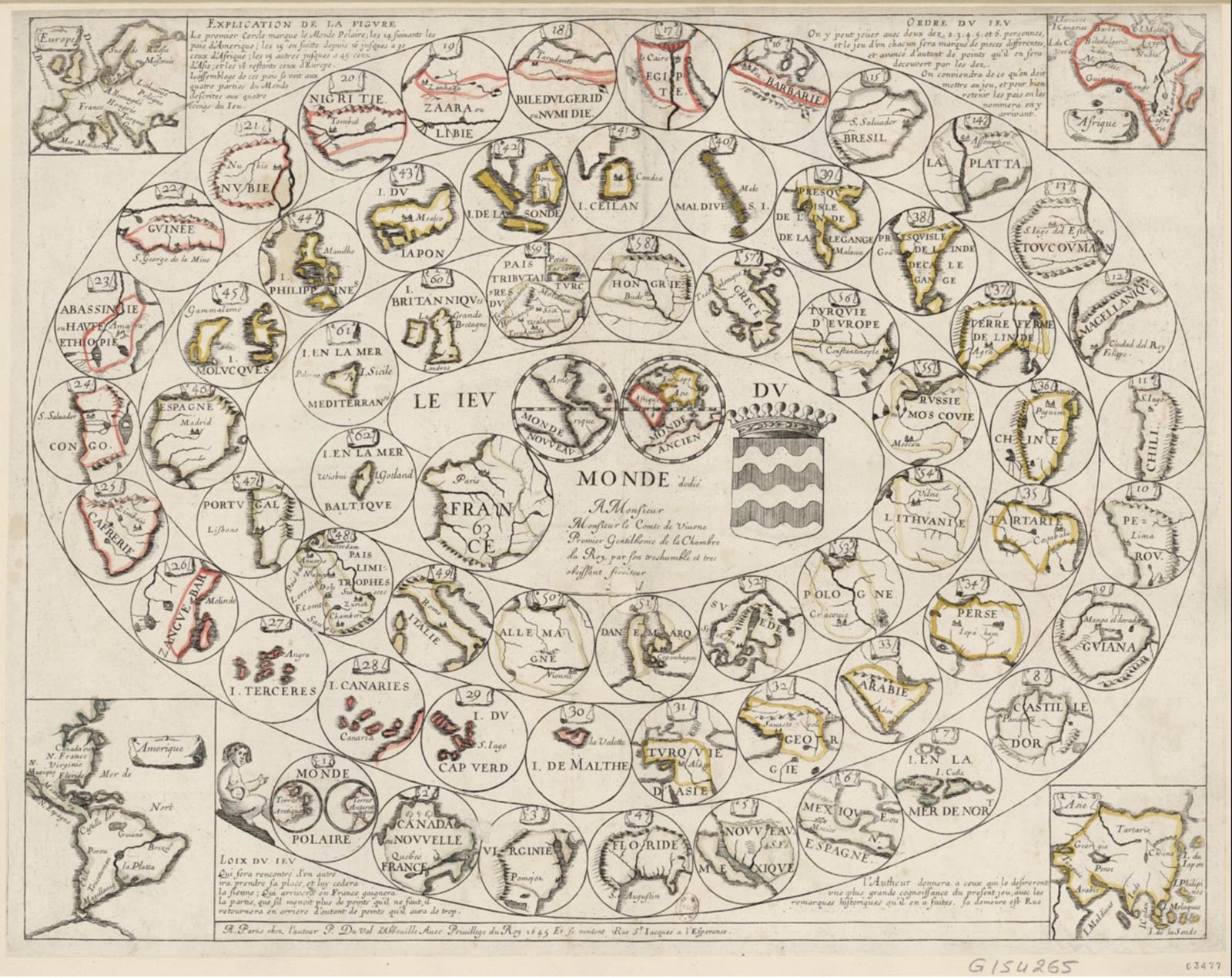

The Bowles family was not the first to manufacture amusements of this ilk. That title is held by Pierre Duval, whose Jeu du Monde (1645) organized the “world” into a snail-shell spiral, beginning with “1. Monde Polaire” and ending in “63. France.” More adaptor than inventor, Duval worked with the Jeu de l’Oie (Game of the Goose) model that had been popular across Europe since the sixteenth century. He kept two of its characteristic features—sixty-three spaces and monetary stakes—but his image-heavy helix went easy on delays and instruction.[4] Locales lacked individual descriptors, so players lost no time learning other languages or discovering the horrors of Protestantism. Didacticism came later, when the model finally took off across the Channel thanks to John Jefferys’s 1759 game, A Journey through Europe, or the Play of Geography. In that century gap, however, the jeu had assumed quite a different form.

Jefferys replaced Duval’s spiral with a Mercator projection, ignored the sixty-three-space anserine convention, and cut any invitation to gamble. Instead, the first to return to “No. 77 at London wins the play, shall have the honor of kissing the King of Great Britain’s hand and shall be knighted and shall receive the compliments of all the company in regard to his new dignity.” Monarchic through and through, the rules decreed that players landing on “any number where a King lives” would benefit from a double roll. Never mind that the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) was currently underway. Would anyone sped along by Frederick II in Berlin have received the helping hand of Louis XV?

Though A Journey through Europe lacked political savviness, it did value knowledge, and seems to have introduced the lasting fixture of instructive delays. In Frankfurt an der Oder, one turn was required to purchase “Printer’s Black to send to England”; after another in Mainz, “to see the Art of Printing which was found out there by John Faustus in 1440,” you’d even know how to use it when you returned. Unless, of course, you were derailed by popery. Anyone visiting Rome was assumed to be “kissing the Pope’s Toe” and would be “banished for his Folly to No. 4 in the cold island of Iceland and miss three turns.”

If these rules sound similar to Bowles’s, you may have an ear for board game plagiarism. Our earliest surviving copy of A Journey through Europe features the publication line: “Printed for CARINGTON BOWLES, Map & Printseller, No. 69 in St Pauls Church Yard, London. Price 8s.”[5] That address goes a long way toward explaining what happened next. It had anchored the family business since the late seventeenth century, when Thomas Bowles I began a print publishing trade. His eldest son, Thomas II, took over in 1715, while the younger brother, John, opened his own shop, first in Mercers Hall, Cheapside, then in Black Horse, Cornhill. Each brought a son of their own into the enterprise—Thomas III and Carington I, respectively—but the branches reunited when the former’s early death led the latter to return to St. Paul’s in 1763. His son Henry Carington took over from 1793 to 1830, overseeing the last chapter of a four-generation dynasty.[6]

Over those 150 years, the Bowleses printed everything from mezzotint portraits like George White’s John Dryden (1698) and Thomas Burford’s Jonathan Swift (1744) to landscapes and political satires.[7] For a delightful bit of mise en abyme advertising, I’d recommend Robert Dighton’s A Real Scene in St. Pauls Church Yard, on a Windy Day (1783). Look past the scattered fish and windborne hats, and you’ll see a window with No. 69’s own prints on display.

And then there were the maps. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the firm had acquired the cartographic stocks of Morden & Lea and John Seller, which formed the basis for a century of prints.[8] These ranged from the everyman’s Pocket Map of the Citties of London, Westminster, and Southwark(1725) to the punctilious Improved Map of Wiltshire Divided Into its Hundreds (1763) to the magisterial Plan of London as in Queen Elizabeth’s Days (1775).[9] With Jefferys’s example in mind, Carington Bowles would have had no trouble adapting his inventory to the board game format: one large print, cut into sixteen rectangles, glued to a canvas sheet, then folded into a portable slipcase.

In the following decades, he and his son brought out a full fleet of games. First came The Royal Geographical Amusement, or the European Traveller (1770), which incurred a legal spat with none other than the king’s geographer Thomas Jefferys (no relation).[10] Next was Bowles’s British Geographical Amusement (1780), which stayed domestic with “a Most Compleat and Elegant Tour thro England, Wales, and the Adjoining Parts of Scotland & Ireland.” For more global ventures, one might pick up Bowles’s Geographical Game of the World (1790), and for virtual tours across the revolution-stricken continent, there came Bowles’s European Geographical Amusement (1795). Along the way, Jefferys’s information was judiciously updated. At the century’s end, Paris no longer featured a Pillar-speeding monarch. Instead, one stayed two turns “to contemplate the New French Constitution, to view the Palace of Versailles, and the Scite of the Bastile demolished in 1789.”

What drove the demand for these games?[11] Besides crippling boredom, there was the rapid expansion of Britain’s trade networks and empire, which made geographical knowledge increasingly convertible to economic and cultural capital.[12] In secondary schools, reformers like John Clarke and John Holmes pushed for geography’s inclusion alongside arithmetic and modern languages, while on Grub Street, publishers churned out reference works, encyclopedias, and schoolbooks.[13] In the 1760s, John Spilsbury entered the field with his mahogany-mounted “dissected maps”: an early form of the jigsaw puzzle.[14] Less jovial was King George II’s response to the 1745 Jacobite rising: a rigorous survey of the Scottish Highlands that led to the 1791 establishment of the Ordnance Survey, the still-extant national mapping agency.[15] As its key advocate, Major-General William Roy, declared: “If a country has not actually been surveyed, or is but little known, a state of warfare generally produces the first improvements in its geography.”[16]

Bowles’s Geographical Amusement: anodyne diversion or tool in bringing up the next generation of globe-trotting imperialists? Either way, the culturation likely proved useful. When the continent reopened after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, a new era was dawning in the history of the voyage. Buoyed by steamships and railways, directed by pioneering guidebooks published by Murray and Baedeker, Brits flocked across the Channel in ever-greater numbers—an estimated hundred thousand per annum by 1840.[17] Over the course of the nineteenth century, Tourism replaced the Grand Tour, and we still live by its rules: disdain the Mona Lisa–gazing masses; avow cultural distinction by taking À la recherche to the Café de Flore; make milquetoast critiques of the cult of authenticity. “Tourism,” wrote Jonathan Culler, “brings out what may prove to be a crucial feature of modern capitalist culture: a cultural consensus that creates hostility rather than community among individuals.”[18]

Or so it did until mid-March. Since then, we’ve made like the Georgians, staying home to read and play board games, deferring the “cultural consensus” on beach holidays and studies abroad until political and technological miracles arrive. When they do, will the floodgates reopen? Or will virus-phobia push our touristic hostility toward a new paradigm? How persistent will we find our aversions to a grand tour? How enduring will we find its allures?

For William Hazlitt, inconstancy itself was the point. “It is an animated but a momentary hallucination,” he wrote of journeying. “It demands an effort to exchange our actual for our ideal identity; and to feel the pulse of our old transports revive very keenly, we must ‘jump’ all our present comforts and connections. Our romantic and itinerant character is not to be domesticated.”[19] Perhaps this is what will remember when we start to move again—that we leave home not to be “esteemed the best instructed and speediest traveler,” but for the quiver, the shock, the hallucinatory bliss of finding ourselves briefly different than we are.

- “Voyage—should be done quickly.” Gustave Flaubert, Le Dictionnaire des idées reçues (Paris: Louis Conard, 1913), p. 24.

- See Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century (Oakland: University of California Press, 2014); James Buzard, “The Grand Tour and After (1660–1840),” in The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing, ed. Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); Alison Byerly, “Technologies of Travel and the Victorian Novel,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Victorian Novel, ed. Lisa Rodensky (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Live feeds available here: www.sibch.tv; explore.org/livecams/aurora-borealis-northern-lights/northern-lights-cam.

- Jeux de l’Oie are named after the “goose” spaces that double prior rolls. Standard features include hazards that delay players or send them back to earlier spaces. Fifty-eight is often a “death” space that either exiles you from the game or forces you to begin again. See Adrian Seville, “The geographical Jeux de l’Oie of Europe,” Belgeo, no. 3–4 (2008); Ashley Baynton-Williams, The Curious Map Book (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), p. 40.

- About $50 today.

- Since Carington I did not take over the St. Pauls shop from the Thomas line until 1763, that copy of Jefferys’s Journey is presumably a later printing. See Tim Clayton, The English Print, 1688–1802 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 105–107; Sheila O’Connell, The Popular Print in England, 1550–1850 (London: British Museum Press, 1999), pp. 51–53; and the “Publishers and Printsellers” database on British Printed Images to 1700, which is available at bpi1700.cch.kcl.ac.uk/resources/directory_publishers_B.html.

- Images available here: www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw80085/John-Dryden and www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw75190/Jonathan-Swift.

- Ben Weinreb, Christopher Hibbert, Julia Keay, and John Keay, The London Encylopaedia, 3rd ed. (London: Macmillan, 2008), p. 527.

- Images available here: www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/crace/a/largeimage87929.html; www.rareoldprints.com/p/8018; and www.rct.uk/collection/702180/a-plan-of-london-as-in-queen-elizabeths-days.

- In his bill of complaint, Thomas Jefferys accused Bowles of copying his own game, The Royal Geographical Pastime or the Complete Tour of Europe (1768). Bowles responded that he had purchased the game rights from John Jefferys, that he had used his own firm’s map stock, and that the game’s text instructions were not engraved but printed with letterpress, and so lay outside the jurisdiction of the 1735 and 1767 Engravings acts. The case was sent to a Master in Chancery, and the final decision is not known, but the litigation clearly did little to halt Bowles’s subsequent board game production. See Isabella Alexander, Copyright Law and the Public Interest in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford and Portland: Hart Publishing, 2010), p. 174; Isabella Alexander and Cristina S. Martinez. “A Game Map: Object of Copyright and Form of Authority in Eighteenth-Century Britain,” Imago Mundi, vol. 72, no. 2 (2020); and the “Jefferys v Bowles (1770)” entry on Alexander’s superb Copyright Cartography website: www.copyrightcartography.org/cases/jefferys-v-bowles.

- Other publishers who joined the fray included Robert Sayer and John Wallis.

- “Knowledge of geography,” writes Andrew O’Malley, “and specifically of the raw materials, resources, and agricultural conditions of a given country, was of incredible importance at a time of colonial expansion and broadening international commerce.” See O’Malley, The Making of the Modern Child: Children’s Literature in the Late Eighteenth Century (New York: Routledge, 2003), p. 108.

- For more on school reform, see Ian Green, Humanism and Protestantism in Early Modern English Education (Burlington: Ashgate, 2009), pp. 102–104, and Paul Elliott and Stephen Daniels, “‘No Study so Agreeable to the Youthful Mind’: Geographical Education in the Georgian Grammar School,” History of Education, vol. 39, no. 1 (2010). For more on map publishing in this period, see Barbara McCorkle, A Carto-Bibliographyof the Maps in Eighteenth-Century British and American Geography Books (Kansas City: University of Kansas Library, 2009); available at http://hdl.handle.net/1808/5564. McCorkle records an increase from 18 to 136 geographical texts published in Britain and America between the first and final decades of the century.

- Linda Hannas, The English Jigsaw Puzzle, 1760–1890 (London: Wayland, 1972), p. 20; Diane Dillon, “Consuming Maps,” in Maps: Finding Our Place in the World, ed. James Akerman and Robert Karrow (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), p. 340.

- See Rachel Hewitt, Map of a Nation: A Biography of the Ordnance Survey (London: Granta Books, 2010).

- William Roy, “An Account of the Measurement of a Base on Hounslow-Heath,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 75 (1785), p. 385.

- Steam vessels began crossing in 1821, and Karl and Fritz Baedeker and John Murray III brought out their first guidebooks in 1835 and 1836, respectively, though “anything like a seamless trans-Continental rail system remained the haziest of utopian dreams for much of the nineteenth century.” See James Buzard, “The Grand Tour and After,” pp. 47–48.

- Jonathan Culler, “The Semiotics of Tourism,” in Framing the Sign: Criticism and Its Institutions (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), p. 4.

- William Hazlitt, “On Going a Journey,” The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, vol. 4 (London: Henry Colburn and Co., 1822), p. 22.

Colton Valentine is a PhD student in the English Department at Yale University. His writing has recently appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Henry James Review, and Review of English Studies.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.