1485.0 kHz

Friedrich Jürgenson and the voices of the dead

Carl Michael von Hausswolff, assisted by M. S. C. Harding

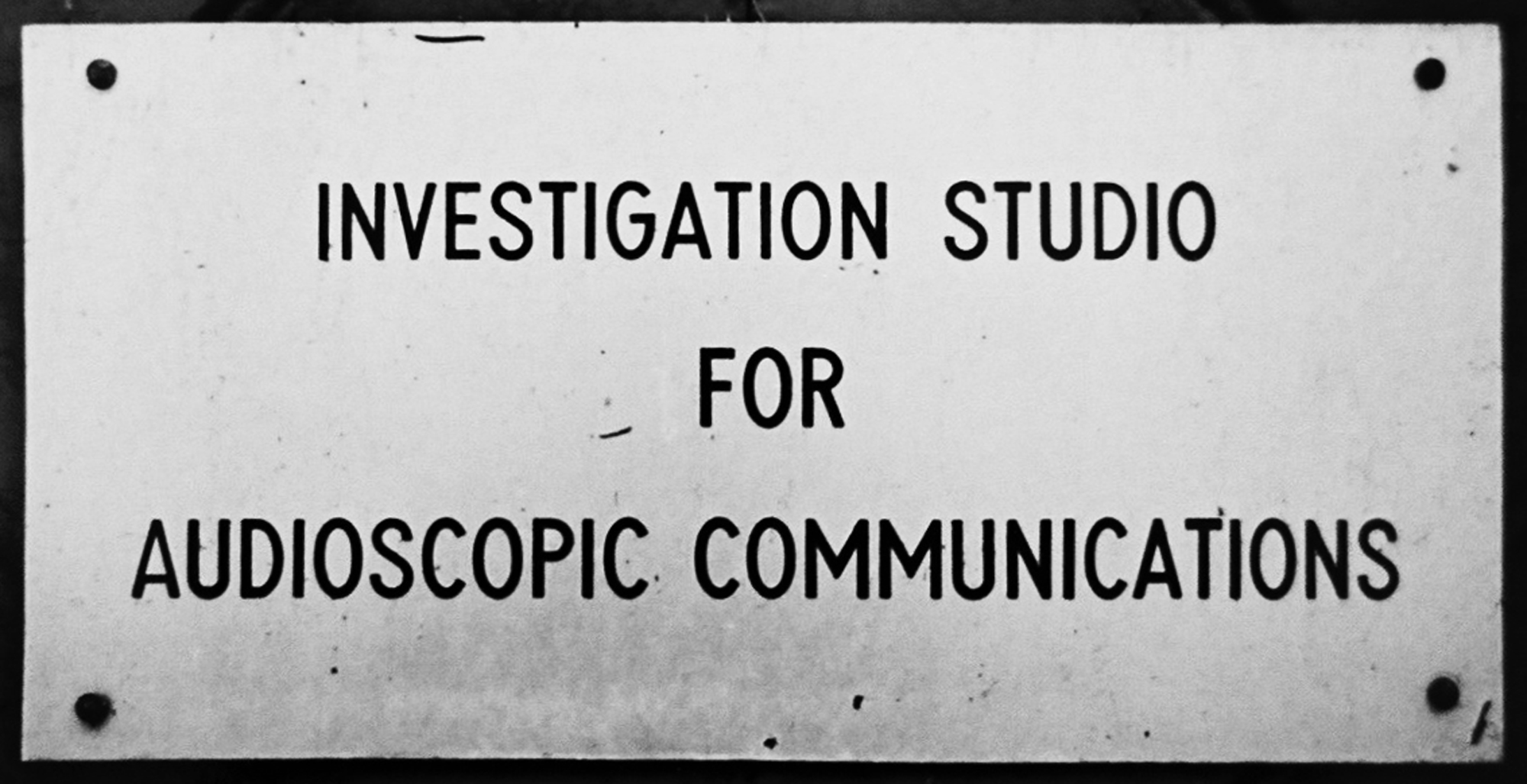

Both Guglielmo Marconi and Thomas Edison believed in the possibility of using new recording devices to contact the dead, or the “living impaired,” to use Edison’s uncanny twenty-first century term. Sir William Crooks, President of the Royal Society and inventor of the cathode ray tube, and Sir Oliver Lodge, one of the leading contributors to radio technology, believed the other world to be a wavelength into which we pass when we die. In the 1950s, Friedrich Jürgensen, a painter, archaeologist, and former opera singer living in Sweden, found traces of extra voices on tapes with which he was trying to record birdsongs. Over the years, Jürgensen made thousands of recordings of the voices of the dead, ranging from his family and friends to people such as Vincent van Gogh and Himmler’s masseur. These are claimed to be the world’s first recordings of Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP), the paranormal appearance of strange voices on magnetic tape. The following is a sketch of Jürgenson’s life and his remarkable and persistent “audioscopic research” into contacting the dead. Some of the recordings from Jürgenson’s vast archive have recently become available on the CD Friedrich Jürgensen: From the Studio for Audioscopic Research (Ash International).[1]

Driven out by war in that year he moved to Sweden. Located in Stockholm, he married and became a Swedish citizen. Here he also learnt his tenth language. During the following years he painted portraits of wealthy Swedes and of the town of Stockholm. In 1949, he visited Pompeii in Italy and in order to get easier access to the buried city he showed some of his work to the Vatican. A few days later he received a proposal: the Vatican recognized his talents and asked him to catalogue their archaeological works buried beneath the Holy City. He returned the following year and for four months sat in this damp underworld, painted, and contracted pneumonia. The Vatican medics cured him and when Pope Pius XII saw the results of his work he asked Jürgenson to paint a portrait of him. In all, Jürgenson produced four portraits of the Pope. Now he had full access to Pompeii as well, and he returned there many times to paint.

In the following year Jürgenson had his first major exhibition amidst the ruins of Pompeii.

Back in Stockholm his telepathic contacts continued:

I sat by the table, clearly awake and relaxed. I sensed that soon something was going to happen. Following an inner pleasurable calmness, long sentences in English appeared in my consciousness. I did not perceive these sentences acoustically but they formed themselves as long phonetic sentences and after a closer study I couldn’t conceive the words as correct English but in a disfigured almost alphabetical way—completely deformed. I did not hear a voice, a sound, or a whisper. It was all soundless.

Later he also recalled that in the spring of 1959 he “got a message about a Central Investigation Station in space where they conducted profound observations of Mankind. ... My friends spoke about certain electro-magnetic screens or radars, that were frequently transmitted, day and night, in batches of thousands to our three-dimensional life levels and, like living beings, had a mission as mental messengers. Undoubtedly one could see these radars as half-living robots that, remote controlled, had the ability like an oversensitive television or radio to correctly register and transmit all our conscious and unconscious impulses, feelings, and thoughts.” Jürgenson knew that these fantastic facts really belonged to science fiction but he continued hoping to capture these messages on tape.

On 12 June 1959, Jürgenson and his wife Monica went to visit their country house to enjoy the warm summer. Jürgenson brought his tape recorder to record the singing of wild birds, especially the chaffinch.

Listening to the tape he “heard a noise, vibrating like a storm, where you could only remotely hear the chirping of the birds. My first thought was that maybe some of the tubes had been damaged. In spite of this I switched on the machine again and let the tape roll. Again I heard this peculiar noise and the distant chirping. Then I heard a trumpet solo, a kind of a signal for attention. Stunned, I continued to listen when suddenly a man’s voice began to speak in Norwegian. Even though the voice was quite low I could clearly hear and understand the words. The man spoke about ‘nightly bird voices’ and I perceived a row of piping, splashing, and rattling sounds. Suddenly the choir of birds and the vibrating noise stopped. In the next moment the chirping of a chaffinch was heard and you could hear the tits singing at a distance—the machine worked perfectly!“

From this point, Jürgenson continued to investigate these phenomena and at first he thought it was his “friends from outer space,” but very soon he began to believe that these voices were “from the other side,” or the “Voices of the Dead.” Was he close to solving one of the fundamental mysteries of death?

At this moment, Jürgenson experienced a remarkable event that would change his life:

I was outside with a tape recorder, recording bird songs. When I listened through the tape, a voice was heard to say “Friedel, can you hear me. It’s mammy. ...” It was my dead mother’s voice. “Friedel” was her special nickname for me.

At this point, Jürgenson abandoned painting for his audio recordings and in 1964 he published Rösterna från Rymden (“The Voices from Space,” published by Saxon & Lindström Förlag in Stockholm).

“My love for the arts was still alive now as ever, and I asked myself if it was the right thing for me to abandon the art of painting—a creative occupation to which I had dedicated my whole life.” Later, he writes: “Instead, I was sitting here with an enormous jigsaw puzzle brooding in despair over the problem of whether one could assemble a more complete picture from all these fragments. And, likewise ... I had never before been so touched and captured by any other urgencies than by these mystical connections, literally floating in the ether.”

Now located in Mölnbo, south of Stockholm, Jürgenson held his first press conference. The Swedish press was stunned by Jürgenson’s scientific approach to these matters, and was understandingly critical. The International Paranormal Societies, as well as the Max Planck Institute, the University of Freiburg, and the Parapsychological Association in the USA, also took a keen interest. Others, like Konstantin Raudive and Claude Thorlin, came to visit and began to work with tape recorders.

At first, Jürgenson only used a microphone and a tape recorder. He simply set up the microphone, set the recorder on ‘record,’ and spoke clearly into the room, leaving space for voices to respond. This was a bit tricky for Jürgenson since he always had to play back the tape, sometimes at a lower speed, to hear the voices. These voices spoke in a combination of various languages —Swedish, German, Russian, English, Italian—all languages that Jürgenson knew and could speak. He called this new mixture of languages “polyglot,” or, “many tongues.”

In spring 1960, one of the voices told him to “use the radio” as a medium and this was the technique he used until his death. He connected a microphone and a radio receiver to the tape recorder and in this way he could have a real-time conversation with his “friends.” Usually, he set the radio reception in between frequencies where there is generally a variation of noises. Later, he fixed the receiving frequencies to around 1445–1500 kHz. (1485.0 kHz is now called the Jürgenson frequency.)

In 1965, Jürgenson took up painting again but recording remained his main activity. At this time, he also revisited Pompeii and found that the site was being mistreated. Sponsored by Swedish National Television, he made the documentary film Pompeii: A Cultural Relic That Must Be Preserved in 1966. A vast output followed in the ensuing years from this highly energetic and creative figure.

In 1967, his book on EVP, Sprechfunk mit Verstorbenen, was published by Freiburg’s Verlag Hermann Bauer KG. In 1968 Jürgenson made four documentaries: The Temples at Paestum and the City of Temples and Graves, a film on the ancient Greek city south of Salerno; The Death of Birds In Italy, about the purposeless killing of birds in Italy; The Miracle of the Blood of St. Gennaro, about the famous blood phenomenon in Naples; and a film documenting Jürgenson’s own archaeological diggings at Pompeii. In 1968, his third book was published in Swedish: Radio och Mikrofonkontakt med de Döda (“Radio and Microphone Contact with the Dead,” published by Nybloms in Uppsala). Rome was impressed with Jürgenson’s documentary output. The result of his work at Pompeii was another mission for the Vatican, and in 1969 his documentary The Fisherman from Gallilee: On the Grave and Stool of Peter was finished. For this, Jürgenson received the Order of Commendatore Gregorio Magno from the hand of Pope Paul VI. Shortly after, he also made a film about the life of the Pope, and Paul VI’s high regard for this film prompted him to contact Jürgenson again. Jürgenson then painted three portraits of his second Pope. Around this time, he was also permitted to conduct his own archaeological diggings in Pompeii and he dug out the large house of the governor in Pompeii.

In the 1970s, Jürgenson continued to record and paint. Moving from Mölnbo to Höör in Skåne, southern Sweden, he found a more peaceful place for his work. Age began to take its toll and Jürgenson spent more time with his recordings at home, making an occasional trip to Italy. There was also serious talk about founding an EVP research institute in Italy. In 1978, he held his third press conference and gave a large number of lectures. Here, he predicted that we will soon be able to receive messages through television as well. He labeled the work “Audioscopic Research.” His German book was translated into Dutch, Italian, and Portuguese at the beginning of the 1980s. In 1985, he held his last press conference in conjunction with a nationwide television appearance.

Friedrich Jürgenson died in October 1987, leaving behind several hundred tapes of recorded material.

- Ash International and the Parapsychic Acoustic Research Cooperative (PARC) have also released The Ghost Orchid: An Introduction to EVP, which draws heavily on the work of Raymond Cass. For more information about both CDs, see the websites of Ash International and PARC.

Carl Michael von Hausswolff is an artist based in Stockholm. His work has been exhibited in many international events, including documenta X, the Istanbul Binennial, and Site Santa Fe. Von Hausswolff and Leif Elggren are the double monarchs of the Royal Kingdoms of Elgaland-Vargaland. For more information on the kingdom, see here. Von Hausswolff is a contributing editor to Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.