How Little We Know of Our Neighbors

Mass-Observation and the meaning of everyday life

Rebecca Baron

Possible subjects of inquiry:

Behavior of people at war memorialsShouts and gestures of motorists

The aspidistra cult

The anthropology of football pools

Bathroom behavior

Beards, armpits, eyebrows

Anti-Semitism

Distribution, diffusion and significance of the dirty joke

Funerals and undertakers

Female taboos about eating

The private lives of midwives[1]

This eclectic list of largely physical, quotidian behavior was composed by two young Cambridge dropouts, Charles Madge and Tom Harrisson, to announce the establishment of Mass-Observation, an unusual social science project from the 1930s, whose hope was to introduce the British population to itself. Madge and Harrison rejected the press’s characterization of public opinion and suggested that the true nature of Britain’s “ultra-repressed” society was to be deciphered in images and objects of everyday life; sublimated meaning was to be discovered and decoded in the street.

The movement formed in the wake of Edward VIII’s decision to abdicate the British throne in 1936 for the love of American divorcée Wallis Simpson. The abdication created an uproar in England that is difficult to appreciate today—a constitutional crisis that called into question England’s identity as a participatory parliamentary democracy. A public exchange of letters regarding the abdication in January 1937 brought a small group together, who declared that the press and the Establishment were out of touch with the public and had no idea what people really thought about the abdication or, for that matter, anything else. They proposed to bridge the gap by conducting what they termed “an anthropology of ourselves.” In describing the Mass-Observation Movement, they wrote:

Mass-Observation develops out of anthropology, psychology, and the sciences which study man, but it plans to work with a mass of observers. Already we have fifty observers that work on two sample problems. We are further working out a complete plan of campaign, which will be possible when we have not fifty but 5000 observers ….It does not set out in quest of truth or facts for their own sake or for the sake of an intellectual minority, but aims at exposing them in simple terms to all observers, so that their environment may be understood and thus constantly transformed. Whatever the political methods called upon to effect the transformation, the knowledge of what has to be transformed is indispensable. The foisting on the mass of ideals or ideas developed by men apart from it, irrespective of its capacities, causes mass misery, intellectual despair and an international shambles.[2]

The movement’s diversity and often contradictory goals were present from the beginning and reflected in its founding members. Madge was a surrealist poet and journalist; Harrisson, an ornithologist and self-styled anthropologist, had recently returned from a three-year stay on the New Hebrides island, Malekula, where he had lived among the headhunters and written the book Savage Civilization. Their mission was to collect data and to refrain from judgment and analysis with the idea that information could be pure. In this mode, Harrisson stated that the ideal instrument for observation was an earplug. He advised, “See what people are doing. Afterwards, ask them what they think they are doing, if you like.”[3]

Looking back in the 1970s, Harrisson wrote:

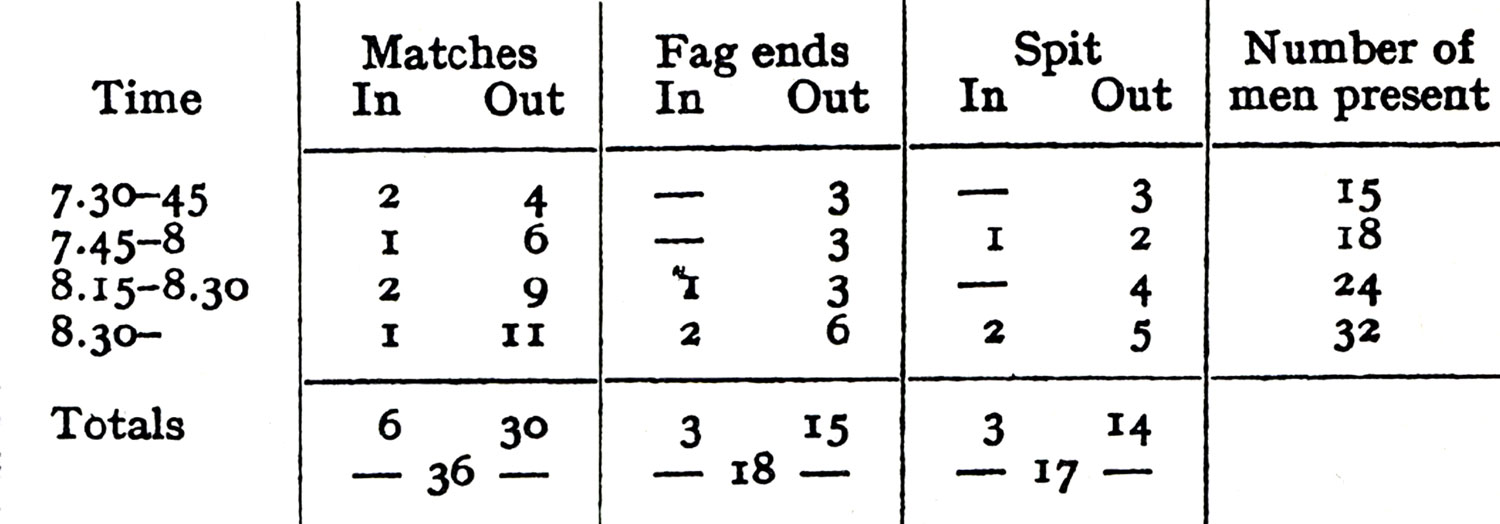

We believed in looking at situations and observing people. We did not believe that you could short cut to the truth by asking strangers in the street or on the doorstep what they thought about every subject …. to be able to operate in our way, it was essential to do exactly the opposite of the modern interviewer. We did not wish to produce “stranger situations.” We had to become assimilated into the society we were studying—and into all of its parts. So our observers joined each of the political parties, every club, pub, society, corner organization and gang ….Observers were trained to observe and record on the spot without being noticed so that life continued as if there were no “strangers.”[4]Through newspapers all over England, they recruited volunteers to record and report on the true nature of daily life. They conducted polls, distributed questionnaires, and enlisted “official” observers to take detailed notes of people’s behavior in public places. Observers were sent out into the street, the pub, and under the pier. Armed with stopwatches, they entered the cinema and timed the length of the audience’s laughter. They spied on young couples kissing by the sea. They counted the number of pints consumed in an evening at the pub and the amount of time it took to drink them.

Harrisson set up headquarters in Bolton, a Lancashire mill town, where he supervised a three-year survey of daily life called the Worktown Study. The study produced voluminous materials on the leisure and work habits of Boltonians and included a related study in Blackpool, the seaside town where the citizens of Bolton took their holidays. Here the aim was to investigate the difference in people’s behavior during the one week in the year away from their usual routines. Their sexual habits were of particular interest:

What actually happens—11:30 p.m., a fine evening on the Prom:The sea is rough, the sand covered

2 men, 2 women. One girl lies on a form, knees pointing up; boy stands gazing down on her.

2 men walk slowly south, larger with left arm round other’s neck.

1 man, 1 woman. Kiss, arms clasped round shoulders, 35 secs

1 man, 1 woman. He fondles her breasts.

2 men, 2 women. Separate couples. Kiss standing.

1 man, 1 woman. He gazes into her eyes. Kisses her neck, rubs her nose with his moustache. They peck. She looks up. They talk.

She clasps handbag. They cuddle. She tries to press him to her lips. He kisses her neck. She rises from form, tightens her girdle.

He presses her breast, drawing her down. They cuddle. He does not kiss her. They both get up, he towards station.

2 men, 2 women. One man presses girl under him, on railings. Look at waves. Straighten to look at two people. Man eases position. Sticks out backside. Leaves girl, goes to left, blows nose and wipes mouth. Takes hanky out of right trouser pocket, puts it in left.[5]

Despite claiming that they were not interested in invading private lives, Mass-Observation was periodically criticized by the press. Humphrey Spender, Mass-Observation’s official photographer, said: “There was an uncomfortable element of spying in all this and the press was often hostile. We were called spies, pryers, mass-eavesdroppers, nosey parkers, peeping-toms, lopers, snoopers, envelope-steamers, keyhole artists, sex maniacs, sissies, society playboys.” In one extreme example, an observer proves himself nothing less than a Peeping Tom:

Leslie Taylor: Undressing in the East End, 5 February 1939Description of male, 25 cockney (Irish) undressing for bed. Time 11.40 to 11.48.40 p.m. Light was originally switched on in room. Male came into bedroom dressed in blue shirt, dark suit, only. He undid the front of his braces and slung them over his shoulder, sat down on bed, immediately got up and lit a cigarette stood facing bed smoking his cigarette, 20 secs. Talking and motioning with his arms to someone already in bed, 10 secs. Sits down on bed again and strokes chin with his right hand, 5 secs. Pulls off his tie without undoing the knot, throws it over bed rail. Bends down and takes off his shoes, throws them to other side of room away from bed. Holds his head in his hands, 25 secs. Rolls up his shirt sleeves, picks his nose with his left hand, and rubs it on his shirt. Throws cigarette into fireplace (not visible), scratches back of his head with right hand. Motions to person in bed and shows the motions of a boxer an exhibition lasting 15 secs, scratches his back with right hand, pulls off his trousers, sits on bed and rubs his hand round his balls. Gets up and rubs his legs from ankles to knees. Stands up erect and goes over to fireplace, folds his trousers and goes over to bottom of bed putting them carefully over the rail. Sits down on bed, picks up newspaper from floor, looks casually at front page, stands up, climbs on bed, throws back clothes and slides slowly into bed and pulls clothes over him. Time taken 8 mins. 40 secs.[6]

While Harrisson carried on in Bolton and Blackpool, Madge was living in Blackheath, London where he organized the Day Surveys project. These were monthly diaries solicited from the public. Participants, also called Observers, were asked to send in a detailed description of a day’s activities on the 12th of each month. They were also asked to answer a “directive” regarding any number of subjects, from how well people knew their neighbors to what they found embarrassing to what they thought about the rat problem in London. These diaries and directives more closely fulfilled the idea of an “anthropology of ourselves.”

A woman in Kent describes her 12 July 1937:

The theme of the dayMain theme of the day was a regret for a wasted week-end that could have been very happy. In spite of this, however, and almost as a background to it, was the ever-present conviction that things are going to be alright here. Impossible to say what is meant by alright, but the feeling has been with me ever since I turned the key in the door of this house that has been the very first to feel home to me in all the years of my married life. It was nothing to do with appearances for everything bore an air of neglect and one wall of dining room was soaking wet and mildewed from an overflow left running for weeks. How then to account for this sudden conviction that came to me then and has persisted ever since, that even when I have felt most ill, or when depression has claimed me neither am I sure that it’s just because I want it so much because I have wanted it for more and worked harder for it in other times and yet have not had this alright come true. We shall see.[7]

The outbreak of World War II gave Mass-Observation a focus that it had not previously had. Surveys and questionnaires took up such issues as the public’s reactions to be being bombed, air raids, anti-Semitism, rations, reconstruction, and victory parades.

Many of the diarists faithfully continued to write throughout the war. One diary in particular, written by a woman named Nella Last, is a unique and remarkable memoir. She was a housewife living in Barrow-in-Furness, a shipbuilding town that became a target of German bombing during the Blitz. Last began writing in September of 1939 and continued for nearly 30 years. The diary records her opinions about the events of the war and provides vivid accounts of what life was like in England during the Blitz. She also writes frankly about her feelings about her family and her frustration at the societal limitations she faced as a woman.

Monday 25 September 1939: I‘ve got a lot to be thankful for. Even the fact—which often used to stifle me—that my husband never went anywhere alone or let me go anywhere without him, has settled into a feeling of content.Sunday 8 October 1939: Next to being a mother, I‘d have loved to write books—that is if I had the brains and the time. I love to “create” but turned to my home and cooking and find a lot of pleasure in making cakes etc. He [her son Cliff] seems to have got the idea that I‘ll go into pants! Funny how my menfolk hate women in pants. I do myself, but if necessary for work, would wear them.

Tuesday 5 March 1940: Mrs. Spencer is a polished, well dressed woman with immaculate hair, complexion and hands. We talked of our sons, her boy is on a hush hush boat somewhere. As she packed, I saw her hands and her once beautiful nails were bitten to the quick. Then I seemed to notice her too bright eyes and I thought of all the mothers whose boys have gone to fight and who suffer and I felt pity wrap me like a flame.

Wednesday 15 January 1941: I gave Cliff a very big helping as he had to catch the train back [to his base] after lunch. He said ‘If you ever have to work for a living, Mom, come and cook for the Army’. I said ‘What do you mean—work for my living. I guess a married woman who brings up a family and makes a home, is working jolly hard for her living. And don‘t you ever forget it. And don’t get the lordly male attitude that thinking wives are pets—and kept pets at that.’[8]

Harrisson, who was always looking for sponsorship for Mass-Observation, struck a deal with the Ministry of Information for Mass-Observation to gather and report on data regarding wartime morale and the effectiveness of wartime propaganda. Although the cooperation between Mass-Observation and the government lasted only a short time, the eventual revelation of the arrangement created a sense of betrayal among many of its participants. An undergraduate at Cambridge wrote:

While I am at any time ready to assist an impartial organization whose object is to collect and fearlessly to publish the truth; yet when that organization seeks and obtains official Government support, I am afraid I must dissociate myself from its activities. When, and if, you obtain freedom from official association after the War, I shall be pleased to join with you once again.[9]Madge was also unhappy at Harrisson’s willingness to cooperate with the government. Their relationship had never been easy, and in 1940, Madge left Mass-Observation to work for the National Institute of Economic and Social Research. In 1941, Harrisson joined the army and was sent to Borneo. Still, a small dedicated staff kept Mass-Observation running. The end of the war was the undoing of the project. Harrisson returned briefly to Britain in 1946, but soon left to become the director of the Sarawak Museum in northern Borneo. Mass-Observation’s fate in 1949 was to become Mass-Observation Ltd., a market research firm. The irony of this evolution must, however, be qualified. Although Mass-Observation had started as an anti-establishment organization, from early on it had provided information about the public’s consumption habits to private industry.[10] The concerns of Mass-Observation’s pre-war studies lose some of their silliness when regarded in this light. Surveys of people’s feelings about margarine and how many men are wearing caps in the pub echo contemporary market research.

Although the market research firm continued work for several decades, Mass-Observation as an anthropological research project terminated in the early 1950s, and in 1970 its archive was acquired by the University of Sussex. Since 1981, the Mass-Observation Archive at the university has resumed the diary and directives projects. The internet has been instrumental in recruiting participants. Recent directives ask observers to comment on:

Daily use of numbers

Feelings about higher education

War in Iraq

Opinions about the BBC

Attitudes toward Americans

Sending emails to the wrong person

What counts as a love letter

Further Resources

In addition to the books cited above, the Mass-Observation Archive has a very informative site at www.sussex.ac.uk/library/massobs. The archive is a public service open by appointment. For extracts from postwar diaries, see Simon Garfield, ed., Our Hidden Lives (London: Ebury Press, forthcoming). For a description of the Mass-Observation project and its relationship with anthropology, see Dorothy Sheridan, Brian Street & David Bloome, Writing Ourselves: Mass-Observation and Literacy Practices (Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 2000).

- Tom Harrisson, Humphrey Jennings & Charles Madge, “Anthropology at Home,” New Statesman and Nation, 30 January 1937, p.155.

- Ibid.

- Tom Harrisson quoted in Tom Picton, “Mass-Observation,” in Camerawork, September 1978.

- Britain in the 30’s (London: The Lion and Unicorn Press, Royal College of Art, 1975) p. 3.

- Speak for Yourself: A Mass-Observation Anthology, 1937–1949, eds. Angus Calder and Dorothy Sheridan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), pp. 48–49.

- Ibid.

- Mass-Observation Archive, University of Sussex.

- Nella Last’s War, eds. Richard Broad and Suzie Fleming (Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1981).

- Mass-Observation Archive, University of Sussex.

- According to Dorothy Sheridan, Director of the Mass-Observation Archive, there is, however, no evidence of any income from sales to private industry. A current research project at the Archive is in fact examining the commercial dimensions of Mass-Observation.

Rebecca Baron is a Los Angeles–based filmmaker. Her latest film, How Little We Know of Our Neighbors, is about the Mass-Observation Movement. She teaches at the California Institute of the Arts, School of Film and Video.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.