Life on the Bell Curve: An Interview with Theodore Porter

Redefining mediocrity

Paul Fleming and Theodore Porter

While there have certainly been average men from time immemorial, the concept of the average man is relatively new, the product of the modern science of social statistics in the nineteenth century. With the rise of statistics, discussions of man with respect to the soul or ratio gave way to percentages, expectancies, and risk factors. You just need to crunch a few numbers to tell you who you are: how much you will make, how far you will go, and how long you will live.

Theodore Porter is professor of history and chair of the Center for Cultural History of Science, Technology, and Medicine at UCLA. He has written extensively on the history of statistics and its implications for both scientific thought and everyday life. His books include The Rise of Statistical Thinking, 1820–1900 (1986) and Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life (1995). He is currently working on a book on the history of the scientist. Paul Fleming met with him in Los Angeles.

Paul Fleming: It’s been said that around 1830 there was a paradigm shift from the enlightened or rational man to the average man. Could you elaborate a little on the history of the term “the average man” and what is at stake in this shift—from the man of reason to man as quantifiable and subject to quantification?

Theodore Porter: The enlightened man was also quantifiable, in fact was more obviously quantifiable, than the average man, because enlightenment meant rationality, and rational decisions should reflect a kind of mathematical ordering. The rise of statistics in the early nineteenth century attests to a loss of faith in the power of individual reason, or at least to a new anxiety about the masses. The average man embodied a form of political activity that could no longer be understood as the rationality of probabilistic calculation. In place of individualistic rationality, the age of mass society gave us a collective order of statistical averages. The term “average man” was invented by the Belgian Adolphe Quetelet in the 1830s to support his new quantitative science, a science of the whole population. The average was a way of embracing the whole of society and of giving it an individualized representation. Quetelet’s idea was to found a science of society on the basis of this emblematic figure of the average man, which was taken as typical or representative.

But Quetelet often refers to the average man as a fiction, as a construction. How does “the average man” relate to the life of the living individual?

It is a fiction in the sense that no real person will have all the characteristics of the average man. In some ways you might think of the average man as the basis for a quantitative model, a person whom the ambitious social scientist uses to abstract away from concrete individuality. This was a fiction anchored in reality, and Quetelet even argued that statistics could help novelists and poets delineate characters who would be appropriate for their age. And there are ways in which he made the average man more real than actual, flesh-and-blood human beings. He portrayed the average man as the center of the symmetrical distribution that we know as the normal or bell curve. For Quetelet, this role was comparable to that of an average in the physical science of astronomy. Here the average stands for the true value of something that you’re trying to measure, and the spread of measures around the mean is just a distribution of errors. From the standpoint of science, the statistical, emblematic figure of the average man more closely represents society as a whole than any flesh-and-blood individual ever can. Quetelet’s average, though fictional, becomes more real than the actual people who make up the distribution.

Is the average man the ideal? Should one aspire to be average?

It’s an interesting question because now we tend to see the average as mediocre rather than exemplary. Quetelet wasn’t totally unaware of this aspect. Yet there are a couple of ways he managed to idealize the average man nonetheless. One was by celebrating the stability of the average. While any individual will have highs and lows, being sometimes desperately in love, sometimes obsessed with philosophy or poetry or natural science, wavering perhaps between radicalism and conservatism in politics, the average smoothes over these fluctuations and is therefore more stable. Quetelet was acutely conscious of living in a revolutionary age, not just in the wake of the French Revolution of 1789, but as one who saw his scientific ambitions gravely threatened by the Belgian Revolution in 1830. One reason for idealizing the average is just its stability, its equanimity and its calmness, when the world is raging with passion. A second perspective, which he drew from Aristotle, is to see extremes as vice and the average as virtuous balance. Instead of thinking of a continuum from low ability to high ability, he imagined a spectrum, say, of passion or of politics, where both extremes are dangerous and the average means stability, the foundation of steady progress. I would say, finally, that Quetelet’s average man fits into a system of social teleology, representing not any concrete production of nature, but nature’s intention.

So the average constitutes a kind of natural teleology?

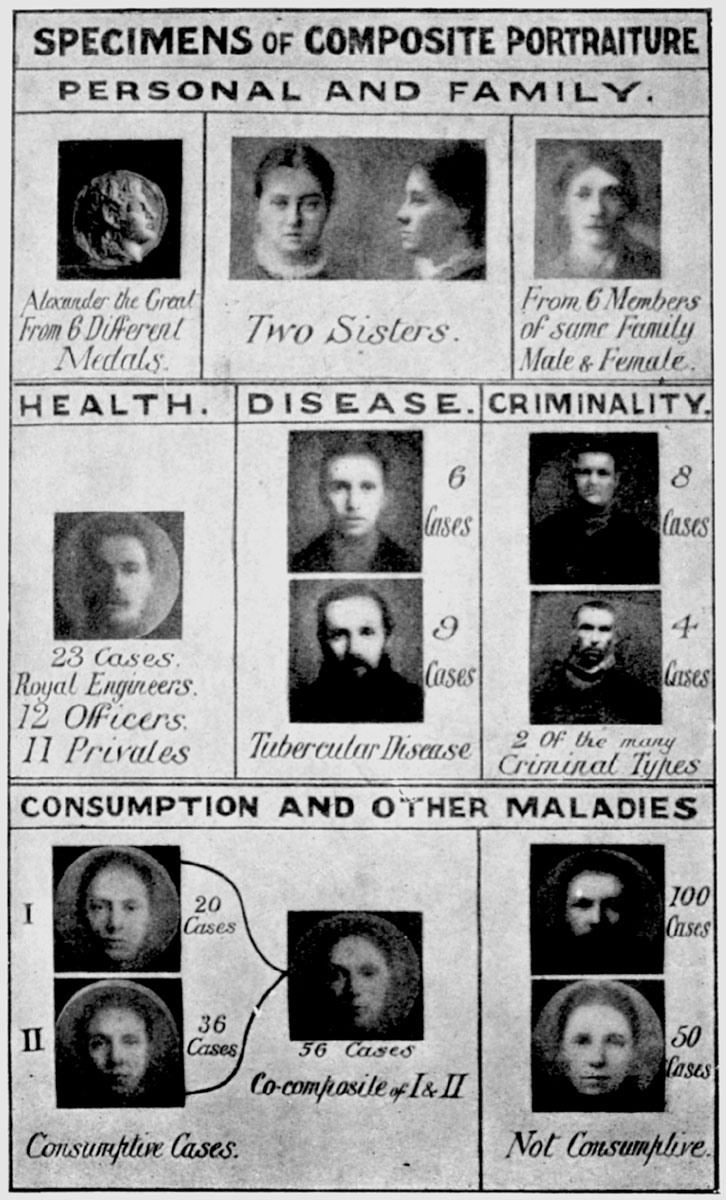

Absolutely. Half a century later, the British biologist and statistician Francis Galton would argue, in the spirit of eugenics, that the average is boring and mediocre and what we need is to cultivate the exceptional. But even Galton thought that averaging could improve an appearance by canceling out peculiarities and defects. This was how he interpreted the composite photographs that he made by superimposing images of several individuals of similar type. Quetelet, too, believed in the beauty of the mean, and with far less ambivalence. The individual was subject to defects of a quantitative kind, involving excess or deficiency, and also to defects in the sense of quirks or oddities, which disappear in an average.

If Quetelet was espousing some form of natural teleology, what role did the notion of the average man play for his political goals of social reform, particularly legislative reform? In his view, society more or less establishes the conditions for the criminal, and all the criminal does is merely carry out the crime. How does his desire for social engineering relate to his belief in a natural teleology?

He wanted to shift focus from the individual to the collective, and to socialize human responsibility, by for example seeking out social and not personal causes of crime. The criminal on the scaffold, he liked to say, is merely an expiatory victim, a passive agent who carries out the deeds demanded by a given state of society, by its systems of law, education, economy, wealth, and religion. The study of averages supported a program of social amelioration based on treating legislation as a kind of social experiment. You try out some new law or a new institution: perhaps you make schooling available to populations that didn’t have it before, and you see how this affects crime or illegitimate births. Then you can design further legislative changes based on that response. It is a vision of society as predictable in a way that the individual cannot be. This recalls the point at which we began. Quetelet was seeking to relocate rationality, which had become problematic at the level of the individual, but perhaps could be recovered at the level of the whole society. Statistics was a form of social reason and, as you say, part of an effort at social engineering.

Many of the early notions of the average man and statistics were gathered from data concerning deviant behavior, behavior that is not average, such as suicide rates, crime rates, and murder rates. How does deviancy, especially volitional deviant behavior, relate to forming the idea of the average man?

Quetelet didn’t have much use for the deviant, and in a way he even feared it. At the same time, he used averages to make deviance normal, which is to say that it was no longer aberrant. What is deviant at the level of the individual—a terrible crime carried out by some monstrous individual—becomes regular and predictable at the social level. To take an average is to displace ourselves from the scene of the action, and thereby to gain a new perspective, somewhere above the earth, from which we survey it. From this distance we see that the present organization of society, its institutions and laws, implies a certain level of theft, murder, and suicide. Our statistical methods and our legislative experiments should give us the means to create a new normal state with narrower bounds of variation. Even if deviant behavior is to be condemned in the individual, Quetelet and then Emile Durkheim interpreted it as normal from the standpoint of society. Michel Foucault, Ian Hacking, and many others have argued correctly that statistics is a way of controlling deviance, by defining the usual as normal and (perhaps implicitly) condemning all else. But I would add that the language of normality, especially statistical normality, also gives us the option of taking a step back and reinterpreting individual deviance as normal and inevitable from a broader perspective. For instance, the Kinsey reports on human sexuality, around 1950, established the figure of 10% as the proportion of homosexuals in the American population. I should say as an aside that this percentage is very high, the result of a broad definition of “homosexual” and perhaps also of the distinctive profile of people who were willing to be interviewed in detail about their sexual experiences. Gay organizations have held onto this high number as evidence that homosexuality is socially or perhaps biologically normal. One might still call it “abnormal” in the sense that this is not the sexuality of the majority of the population, but 10% is widely thought to be too high for homosexuality to be dismissed as contrary to the intentions of nature. While some gays use words like “queer” to convey their defiance of polite respectability, others invoke the figure of 10% to show that homosexuals are normal, even though they are a minority.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, the statistical thought shifted from an emphasis on regularity to an emphasis on variation, on difference. Francis Galton, for example, denounces Quetelet’s average man as mediocre. Galton wants to use statistics coupled with biology to upgrade mankind, to create a more noble, a better race. Could you talk about the relation between Galton’s eugenics and his project of composite photography, which he called “pictorial statistics” and viewed as an immediate congruence between the abstract and the concrete?

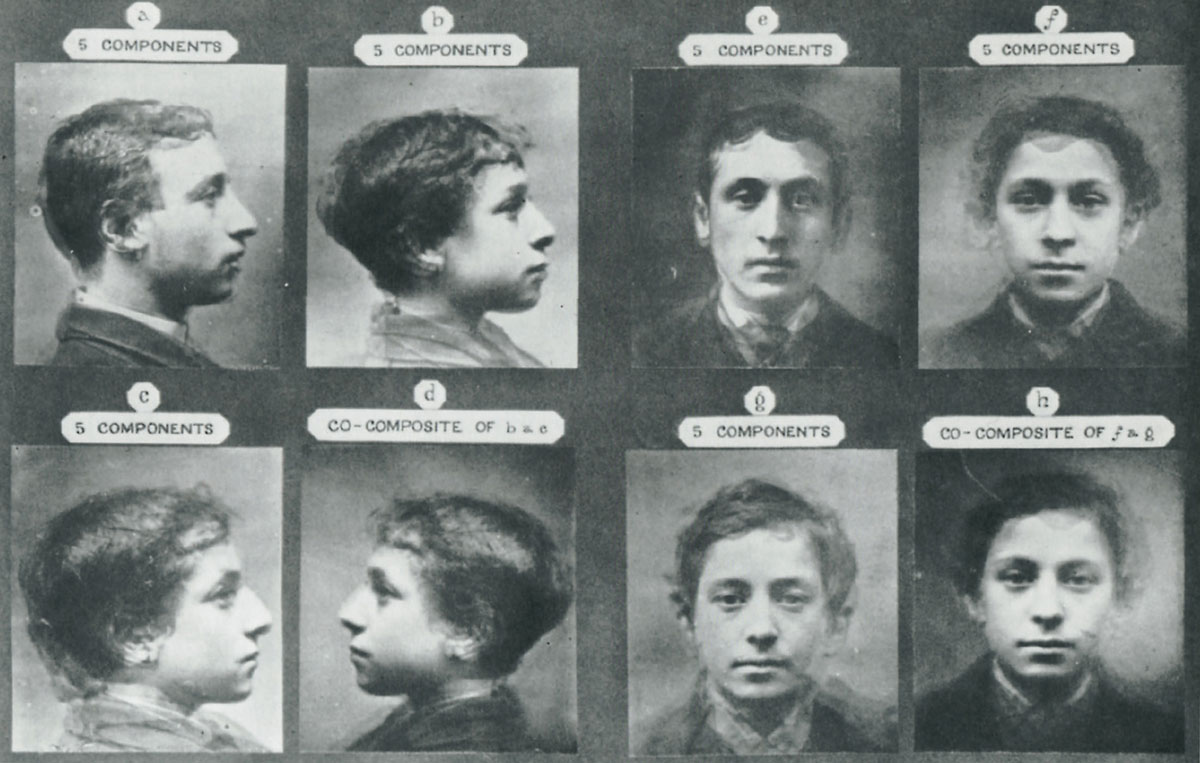

Personally, I find those composite photographs haunting, though it seems that most people at the time were not sufficiently convinced by the humanness of the composite images, with their fuzzy or even indefinite margins. I look at these pictures and see the production by superposition of fictitious individuality, and it is hard for me to think that there was never such a person. For Galton, the composite photographs bore a message about the limits of individuality, which could be merged with others of the same type. These images also were tools for very specific eugenic purposes. The superposition of pictures of mother and father, and of more remote ancestors with reduced weighting, should provide the basis for anticipating results of breeding, at least in horses. In humans, the composite photograph provided a concrete way of blending together the characteristics of a number of individuals. Sounding rather like Quetelet, Galton claimed that this average is usually more beautiful than the individuals who make it up, because the blemishes and defects disappear.

But Galton employs images of criminality or disease, and then juxtaposes them with images of health. So beautiful in what sense?

A short answer is that even the diseased should generally appear more beautiful in an average. But this for him was only incidental, and not the main purpose of the photographs. Galton set out from the premise of a fundamental human heterogeneity, which is not in the first instance statistical. Out of a vast spectrum of variation, he took composite photographs of people from within categories that he took to be homogenous. He even used terms like “race” to describe them: the race of Irishmen, prostitutes, or murderers. Or, in the investigative voice, composite photography could help determine which groups really were homogeneous. He aimed to divide humanity into an array of discrete types, then photograph in a single image the members of a particular type to reveal racial or collective characteristics that no individual can display to the same extent. Galton the statistician was affirming the mean in his composite photographs, but it’s the mean of a certain type, and he insisted on the fundamental heterogeneity of types. This is consistent with one crucial aspect of his eugenic theory: you could never breed a great and enduring change, a whole new kind of individual, if all variation were continuous. Real eugenic progress would require what the nineteenth century called “sports,” or the playfulness of nature, that is, real departures from a type. These would show up statistically as outliers on a frequency curve, distinct from the rest of the population, and not merely as the extremes of the normal curve. A new type would mean a new center of stability, with no tendency to “regress” back to the mean, and you need these discontinuities to make permanent eugenic progress. So in a way, Galton’s statistics remained in Quetelet’s mold, a conservative force, requiring discontinuous variation to escape from the grip of the mean. Still, he seems also to have believed that the children of outstanding parents were most likely to provide the nucleus of a new human type, and in any case he also cultivated a statistical language of exceptionality and greatness. He criticized statisticians who cared only for averages, because that was just praise for mediocrity.

Doesn’t Galton also depart from Quetelet’s political program of social reform and want to form an elite—a eugenic elite?

Galton was much more biological than Quetelet. He argued that biological causes were more important than social ones, and his eugenics campaign reflected that preoccupation. Following Quetelet, he drew a bell-shaped curve to represent normal variation. In most cases, and most certainly for his distributions of achievement or social worth, only one end of the curve was superior to the average, while the other stood for the dregs of humanity. The object of eugenic selection was to cultivate certain forms of exceptionality, at one tail of the distribution, but also to weed out the inferior specimens at the other tail. He was comfortable with stark assessments of human worth, and he drew curves with “genius” on one end, “idiots and imbeciles” on the other. These, for him, were no mere conventions, but real characterizations of the people he was describing. He favored the application of eugenics to shift the population away from failure and away from mediocrity.

So in many ways his big fear was mediocrity.

Certainly he had no fondness for mediocrity, and he appears most supercilious in his descriptions of places where it was to be found, such as social gatherings out in the provinces. In the early twentieth century, reformers began speaking of positive and negative eugenics. Negative eugenics meant blocking the reproduction of people described as criminal, shiftless, or degraded, and often labeled simply as the “residuum.” Galton and Pearson warned of the terrifying fertility of those at the inferior end of their curve. But as a “positive” program, to encourage the reproduction of gifted and creative people, its enemy was indeed mediocrity, which always threatened to swamp genius. Galton’s first book on inheritance, which already was inspired by a eugenic vision, was called Hereditary Genius (1869). He wanted to nurture and cultivate genius of all sorts in the families where, according to his interpretation of historical records, it was present as a biological tendency.

In your recent intellectual biography on one of the founders of modern statistics, Karl Pearson, you quote him as saying “Science is socialism.” How did he see science as socialism?

It’s an argument that makes more sense than it might at first seem. He had in mind the need for a kind of knowledge that stands above the individual. What is a citizen if not someone who can rise above prejudice and self-interest? Pearson, who intellectualized everything, interpreted this moral demand in terms of science. He spoke of scientific method as self-elimination, a choice of impersonal standards over selfish egoism. And it remains a commonplace in our day to speak of the impersonality of science, though few draw out the larger political implications as Pearson tried to do. But if you believe in a “scientific method” that is not limited to specific disciplines, Pearson’s conclusions are hard to avoid. In terms of practical politics, Pearson always defended what he called “socialism of the study,” roughly the science of socialism, over the messy engagement implied by “socialism of the marketplace,” but he was a great admirer of Karl Marx, and in 1881 he proposed himself to Marx as translator of Capital into English. He developed in fragments a historical theory that made socialism inevitable, and a plan for a gradual transition to socialism (for example by announcing the eventual nationalization of land by converting all ownership to 100-year leaseholds), roughly along the lines of the contemporary Fabians, whose society however he refused to join. I have to add that the relation of this scientism to a liberal belief in human individuality is complicated. Until recently I understood Pearson’s philosophical book The Grammar of Science (1892) in terms of a strictly prescribed method that would produce knowledge almost by rote, and in that way would squeeze out wisdom and experience. But Pearson valued high moral standards over mindless routines. He did not regard science as mass-produced knowledge, but as an enterprise that depends on the moral elevation of its practitioners. Science also reinforces these values, and this, as much as any commitment to national efficiency, explains why he wanted to make science the basis of education. You find repeatedly in Pearson’s early work the literary motif of renunciation, which he ascribed to Goethe. This renunciation is an ethical triumph, an achievement of the self. Without renunciation of the self, you can’t have scientific method. So in a way scientific method becomes as much the outcome as the cause of a socialist mentality. In any case, it should enhance rather than threaten the strong self. In his later years, as he became increasingly disaffected with the standardized life, he began to insist on science as a calling rather than a career, and as a way of expressing individuality. He thought of his own life, moving through so many different fields before he settled on statistical mathematics, as a kind of Bildungsroman. In each stage of life one should venture into something new, bringing out aspects of the self that previous experience had not awakened. The good life was a process of advancing individuality. And Pearson eventually brought statistics into this vision. Statistics is fundamental to science, he argued, because of the ubiquity of variation, because each individual is unique. If they were fundamentally the same, it would suffice to have general laws of behavior. The science of statistics and of chance suited a world of infinite variability.

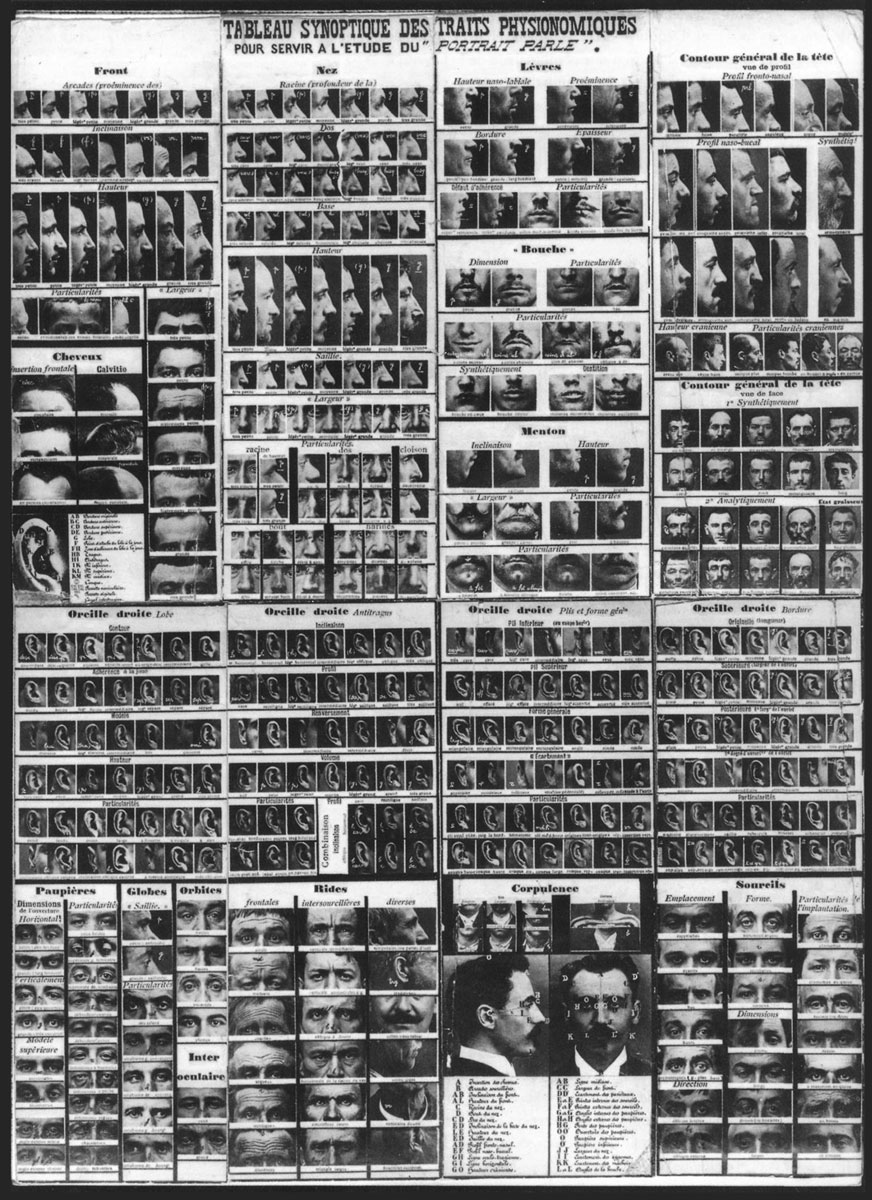

His interest, then, is the exact opposite of Galton’s. Whereas Galton invented a genre of image based on shared physical traits, Bertillon’s system was concerned exclusively with the idiosyncratic.

But how does Pearson reconcile his socialist and his eugenic convictions?

There were many eugenic socialists in the early twentieth century, and in England eugenics was as much a movement of the left as of the right. Really, it had two faces. First is its often profound anti-egalitarianism, an aspect that was always present, even on the left. A century later, this emphasis on inexpugnable biological difference seems reactionary. But here’s how it looked form the standpoint of the eugenic Fabians: If you want a socialist society that will assure the welfare of everyone, you need to build it out of strong material. Pearson put it bluntly, but no more cruelly than the anti-Darwinian George Bernard Shaw. In a world of military and economic struggle among nations, the “residuum” cannot be allowed to outbreed the “fit.” Socialist eugenics seems implausible to us now, and there were many socialists who hated eugenics even in 1910, but there also were conservative opponents, including, perhaps most reliably, the Catholic Church, which chose to leave human reproduction to the family and to God. There is, by contrast, more than a hint of socialism in the willingness of eugenicists who had grown up under Victoria to put the state in charge of sex and reproduction. To be sure, some conservatives reconciled themselves to reproductive intervention by the state, particularly because such controls would be exercised mainly over the poor. Socialists were more willing to bring the rich into this net as well. Pearson was profoundly anti-egalitarian, but he did not accept the old social hierarchies. A consummate meritocrat, he strongly opposed the inheritance of wealth, preferring to have the state endow personal, biological merit.

What are some of the tensions and questions surrounding statistics today? Where is statistical thought going and how could this affect our daily lives now as well as in the coming years?

As a historian, I get nervous talking about the future, and here I speak only as an interested observer. First I would call attention to the extraordinary role that statistical designs and methods have come to play in all kinds of public decisions involving business, engineering, medicine, education, and administrative procedures, as well as the social and biomedical sciences. I don’t see any sign of that declining. In recent times, there has been a strong move to individualize statistical results. Statistics grew up as the science of mass observation and mass society, of collectives and wide averages. Although the controlled experiments described by Pearson’s successor (and bitter rival) R. A. Fisher allowed statistics to be applied to relatively small populations, it was usually with the intention of universalizing the results. But now there are increasingly powerful tools of analysis and data management—I’m thinking especially of computers—that allow the manipulation of information regarding all kinds of subcategories, even rather small ones. In a database of millions or hundreds of millions, few will be so odd or unique that they can’t be grouped with others to support a statistical analysis. Beyond that, there is a great interest now in finding ways to combine categories, and thereby to individualize still further. Let’s say a person with a rare disease has also an unusual genetic makeup. We would like to know not only what treatment gives the best results on average, but also how to modify the therapy in consideration of other relevant characteristics of the patient. The study of the human genome has entered a statistical phase, as scientists try to puzzle out the significance of an endless sequence of base pairs. Molecular biologists generally didn’t recognize, or at least didn’t admit, how hard this problem would be until after the genome was decoded, and I’m not expecting miracles. But this is part of an effort, which surely will produce results, to move from great averages to individualized knowledge. Statistics has always proceeded by grouping and counting rather than trying to fathom the infinite complexities of the individual. This aspect of statistics will not melt away, but the ambition of our time is to tighten and narrow the categories rather than to apply great averages indiscriminately.

Could there be a flip-side to such a re-individualizing of statistics? Couldn’t such re-individualization be used against you?

Yes, individuation has negative as well as positive consequences. Many of the most important institutions of the welfare state depend on a statistical perspective. Social insurance involves what we may call statistical communities, communities that depend on ignorance of details. It’s like the social contract proposed by John Rawls, in which we are imagined to choose political arrangements before we know anything about our station in life. Since we are all subject to medical hazards and don’t know who among us will suffer serious illness, we (more or less) willingly share the risks through taxes or other mandatory contributions. Suppose we were to attain that utopia of scientific medicine, the power to forecast health accurately at an individual level. The purchase of health insurance by individuals would then become impossible or pointless, because insurers would be able to charge very nearly what each specific policy will eventually cost them. Such knowledge would help individuals plan for their financial needs in the future, but the healthy would resist contributing to the medical costs of those less fortunate. Insurance depends on a combination of individual uncertainty with reliable knowledge of the mass. Individualized medical prognostication would solve some important problems, but would tend to create new forms of inequality and also new forms of discrimination by employers, business partners, and—who knows?—maybe lovers and potential spouses as well.

Theodore Porter is professor of history and chair of the Center for Cultural History of Science, Technology, and Medicine at University of California Los Angeles. He has written extensively on the history of statistics and its implications for both scientific thought and everyday life. He is the author of Karl Pearson: The Scientific Life in a Statistical Age (2004) and the co-author of The Empire of Chance: How Probability Changed Science and Everyday Life (1989).

Paul Fleming is assistant professor of German at New York University. He is currently commencing a book project on the aesthetics and politics of mediocrity.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.