Tears of Laughter

Darwin and the indeterminacy of emotions

Christopher Turner

“Between the expressions of laughter and weeping there is no difference in the motion of the features,” Leonardo da Vinci wrote in his posthumously published Treatise on Painting, “either in the eyes, mouth or cheeks.” With the difference between the physical expression of emotions so subtle, artists had a challenge on their hands: How to differentially depict, in the words of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the “frantic joy of a Bacchante and the grief of a Mary Magdalen”?

To do so, artists relied on a staged iconography of expression and posture, codified in handbooks such as Charles Le Brun’s A Method to Learn to Design the Passions (1667), in which Le Brun adapted Descartes’s Passions of the Soul (1649) into a visual lexicon of twenty-four emotions. Here, a menacing portrayal of the laughing face immediately precedes the illustration of a crumpled, crying one, almost as if the expressions were modulations of one another, but with certain differences artificially accentuated, especially in relation to the ruffling of the brow. Thus Le Brun created a stylized, histrionic vocabulary of the passions easily recognizable as tragic or comic on both canvas and stage.

Despite such expert guidance in the depiction of laughter, in the history of art there are very few images of people laughing. Le Brun, who was painter to the king at Versailles, systematized the passions amid an atmosphere of courtly restraint, as if by categorizing these turbulent invasions he could tame them. Laughter was considered vulgar in the eighteenth century as well, a variant of contempt, and decorum dictated that it should be strictly regulated. In a letter to his son in 1748, the moralist Lord Chesterfield proclaimed, “In my mind there is nothing so illiberal and so ill-bred as audible laughter,” especially by virtue of “the disagreeable noise that it makes, and the shocking distortion of the face that it occasions.” In his Laocoön (1766), Gotthold Lessing describes a portrait of the philosopher and libertine Julien Offroy de La Mettrie, in which he is depicted as Democritus, or the “laughing philosopher.” For Lessing, the philosopher’s gaping mouth is a worrying stain; the laugh degenerates into a foppish and repulsive grin, which fills him, he writes, with “disgust and horror.” In The Analysis of Beauty (1753), William Hogarth complained, in a similar vein, that “excessive laughter, oftener than any other, gives a sensible face a silly or disagreeable look, as it is apt to form regular pain lines about the mouth, like a parenthesis, which sometimes appears like crying.”

Nearly half a millennium after Leonardo, contemporary scientists have discovered a neurological explanation for the affinity between physical expressions and emotional sensations of joy and grief. In the centuries between, scientists took over where artists left off in urgently pursuing the question. Charles Darwin notably fused the two approaches, using the art of photography to further his scientific inquiry. In order to formulate The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) with scientific veracity, Darwin broke with both schematic artistic representations of the passions and aristocratic conventions preventing extreme displays of emotion. He hoped to use photography to portray emotional subtleties—like the close similarity between the laughing and crying face—with a renewed realism.

Capturing particular expressions, inherently transitory, volatile, and ephemeral, at first seemed almost impossible with the long exposure time photography then required. (Eadweard Muybridge had only just begun his experiments recording sequences of a horse in motion the year Expression came out.) Darwin described the spasms a laughing fit provoked, which would have rendered any photograph a blur: “During excessive laughter the whole body is often thrown backward and shakes, or is almost convulsed. The respiration is much disturbed; the head and face become gorged with blood, with the veins distended; and the orbicular muscles are spasmodically contracted in order to protect the eyes. Tears are freely shed,” he noted, appending a key observation, “Hence . . . it is scarcely possible to point out any difference between the tear-stained face of a person after a paroxysm of excessive laughter and after a bitter crying-fit.”

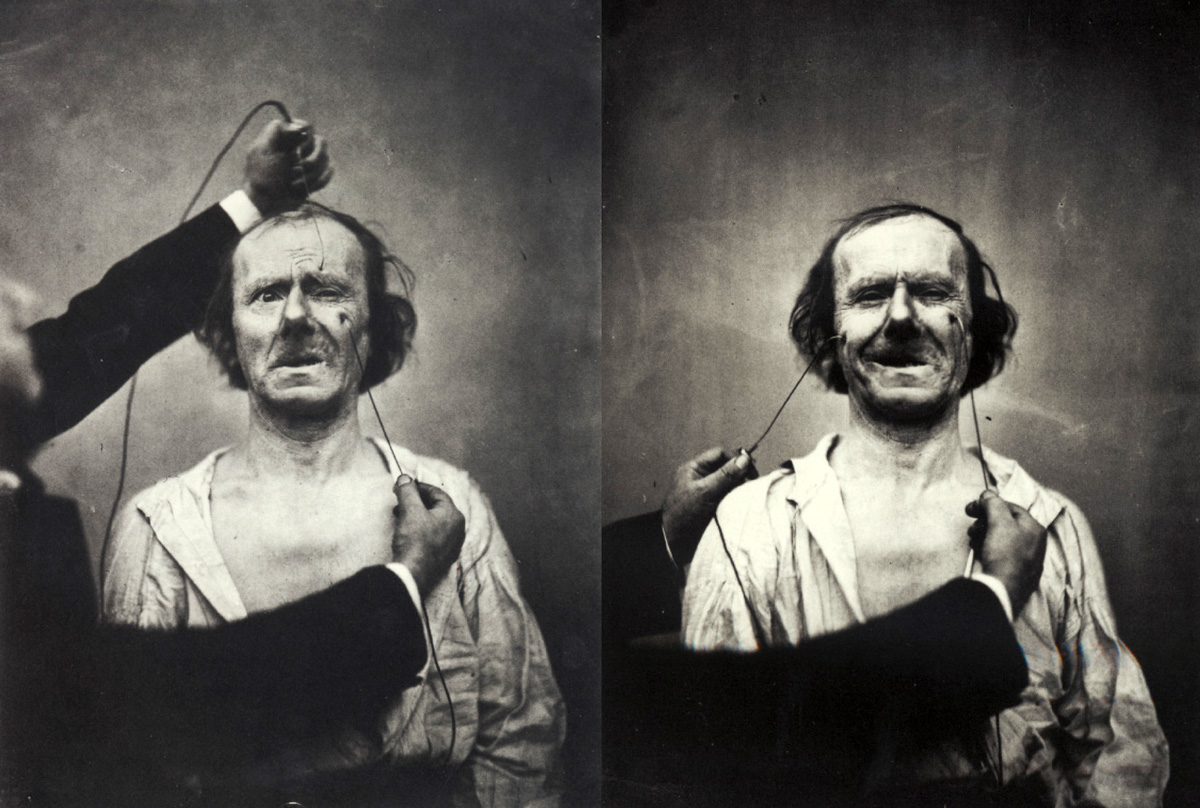

Darwin found a ready-made solution to the problem of how to capture raw expression in a set of extraordinary pictures taken by the French doctor Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne and reproduced in his book, Mécanismes de la physiognomie humaine (1862). Duchenne practiced medicine at the Salpêtrière hospital, where he embarked on an infamous series of experiments in an effort to explain the workings of facial musculature. His process involved administering a constant flow of electric current to human facial muscles, which contorted the face into various expressions and held them long enough for photographs to be taken.

Duchenne took as his primary subject “an old, toothless man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality and whose facial expression was in perfect agreement with his inoffensive character and his restricted intelligence.” The man suffered from palsy, which paralyzed his face and made him impervious to the pain of the electricity. Using his electrical devices, Duchenne could “fake” emotions in his subject, activating and fixing expressions without inflicting torture, as though he were, as he put it, “working with a still irritable cadaver.” The results are disturbing; the use of electrodes, and the hands that hold them in place toward the bottom of the frame, create a distinct impression of sadism. Darwin must have noted this, for in his book, the hands are only visible in the plates depicting benign expressions such as the smile; indeed, for the picture Darwin used to illustrate horror and agony, he instructed the engraver to remove the menacing electrical apparatus and the hands that press it to the skin.

In one of Duchenne’s pictures, which Darwin refers to but does not reproduce (Plate 48 of the Mécanismes), Duchenne galvanized each side of his subject’s—or victim’s—face with a different expression; one half is given a fake smile, the other is made to weep. Duchenne’s intention was to show that the similarity of the two expressions stemmed from the underlying musculature in the marked nasolabial fold, which runs from the wings of the nostrils to the corners of the mouth, wrinkling both cheeks, and which is a characteristic of both the laughing and crying face. Darwin was apparently less than impressed with the results of this particular experiment: “Almost all those (viz. nineteen out of twenty-one persons) to whom I showed the smiling half of the face instantly recognized the expression,” Darwin wrote, “but, with respect to the other half, only six persons out of twenty-one recognized it—that is, if we accept such terms as ‘grief,’ ‘misery,’ ‘annoyance,’ as correct.”

Darwin then turned to the Swedish photographer Oscar Rejlander, who taught photography to Julia Margaret Cameron and Lewis Carroll, to investigate these similarities and differences for him. Rejlander was famous for his large, allegorical photographs and self-portraits; he once portrayed himself in a toga and with a leering grin as Democritus, the laughing philosopher who had so offended Lessing. At the invitation of Darwin, Rejlander posed for four photographs in Expression. He even had his moustache trimmed so as not to obstruct the pantomimic grimaces and decorous gestures he acted out for the camera. But his most famous contribution was his picture of a screaming child, known as Ginx’s Baby, illustrating the chapter on “Low spirits, anxiety, grief, dejection, despair.” Rejlander sold 300,000 prints of this photograph, which almost single-handedly kept his foundering studio afloat.

In the Darwin archive at the University of Cambridge there is a photograph of Rejlander next to Ginx’s Baby. It rests on an easel and by it sits the photographer, mimicking his subject’s expression, his arm around the picture of the baby. Another, almost identical picture appears alongside it, like a stereoscopic slide. “Fun, only,” he wrote on the back of the photograph, “There I laughed! Ha! Ha! Ha! Violently—In the other I cried—e, e, e, e,.. Yet how similar the expression.” It is almost impossible to tell them apart.

Also in the Darwin archive is a slide produced by the London Stereoscopic Company that depicts two sculptures by Adolph Itasse of babies in bonnets, one crying, the other laughing. Normally, a stereoscopic slide would contain two identical images, which would create a 3-D effect when seen through the viewfinder. Here, however, the two sculptures would appear superimposed, their expressions blurring into each other. The composite image would flicker between the two emotional extremes like a hologram.

• • •

Why would the uncanny similarity between the expressions of laughter and crying have so intrigued Darwin? In short, it helped confirm his theory of evolution. Darwin thought that monkeys, like humans, laughed. In this, he disagreed with Aristotle, who claimed that humans were the only creatures who laughed. Darwin’s purpose was to show that the expressive facial muscles had evolved from animals and that therefore man was not a separate, divinely created species. Duchenne kept a pet monkey and reported to Darwin that he’d often seen it smile, but Darwin relied on his own empirical experiments to argue that they laughed as well. “If a young chimpanzee be tickled—the armpits are particularly sensitive to tickling, as in the case of our children—a more decided chuckling or laughing sound is uttered,” Darwin wrote, “Young Orangs, when tickled, likewise grin and make a chuckling sound and. . . their eyes grow brighter.”

Along the way, however, Darwin noted that apes didn’t shed any tears when they laughed. To prove that tears of laughter were a definitively human feature, Darwin, a keen armchair anthropologist, sent a questionnaire to a number of colonial functionaries in the far outreaches of the British Empire asking “whether tears are freely shed during excessive laughter by most of the races of men.” The answer was affirmative. Sir Andrew Smith had seen “the painted face of a Hottentot woman all furrowed with tears after a fit of laughter”; Rajah C. Brooke reported that the Dyaks of Borneo had an expression which meant “we nearly made tears from laughter”; and Mr. Swinhoe informed him that the Chinese, more curiously, “when suffering from deep grief, burst out into hysterical fits of laughter.”

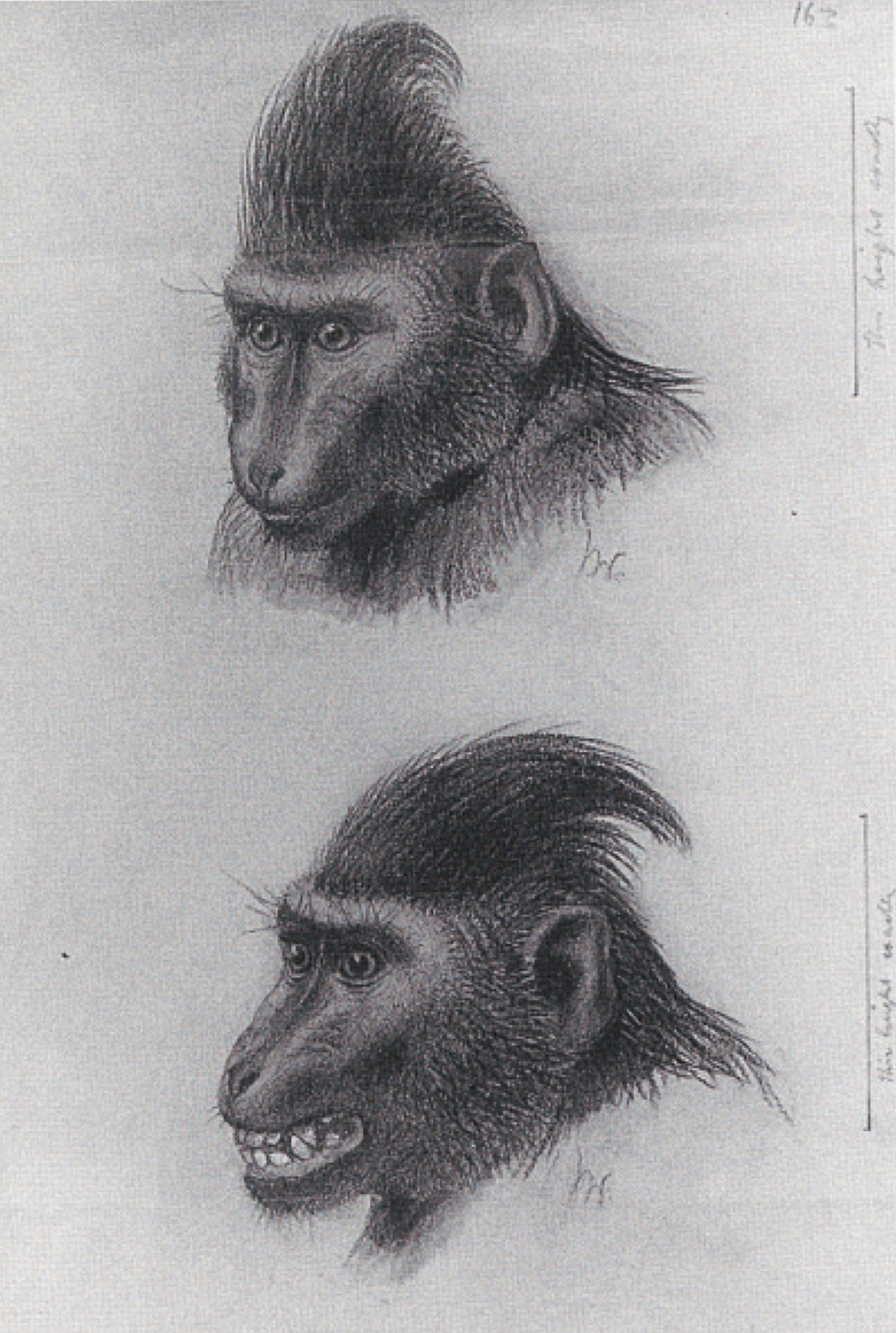

Darwin’s efforts to wring various emotions from our evolutionary forefathers were tireless. As well as tickling apes under the armpits, he gave snuff to chimpanzees to make them sneeze, made faces at orangutans, and watched baboons recoil in horror from a stuffed snake. One such experiment involved hiding a turtle under a heap of straw in London Zoo’s monkey cage. Darwin was hoping to shock the monkeys, thereby evoking expressions of astonishment or terror. The animal illustrator Joseph Wolf, who Darwin claimed had “an eye like photographic paper,” was on hand to record the results: “The Monkeys suspected something and kept looking down from on high,” Wolf wrote in his memoir, “Clever fellows! I shall never forget that. The keeper then retired, and presently the heap of straw began to move. The turtle came out, and instead of showing fear, the Monkeys crept nearer. The back-crested ape came and looked at it, and walked in front of the turtle as it crept under him. Finally he went and sat on the Turtle. Darwin was much amused, and asked for a drawing of the incident.”

The sketch of the scene is illustrated in Expression as Cynopithecus niger, in a placid condition, and The same titillated by sitting on a crawling turtle. The monkey who is riding the turtle is depicted with his impressive crest of hair flattened back, and with the corners of his mouth drawn backwards to reveal a frightening set of chattering teeth with which, according to Darwin, he was making a “slight jabbering noise.” Only “those familiar with the animal,” Darwin admitted, could be absolutely sure he was not baring his teeth but grinning with happiness. Years later Wolf added a skeptical note to his sketch: “I never believed the fellow was laughing, although Darwin said he was.”

• • •

Five years ago, at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, where Duchenne had distorted faces with a galvanized rod, Professor Yves Agid implanted an electrode into the brain of a 65-year-old woman in the hope of discovering a cure for her Parkinson’s disease. The electric current would sometimes alleviate her symptoms, but this time something quite unexpected happened. A melancholy expression came over the patient, her head slumped forward, and she tilted to the right. She began sobbing uncontrollably. “I no longer wish to live, to see anything, hear anything, feel anything,” she wept, “I’m fed up with life.” With another flick of the switch her dark mood was immediately lifted. She smiled and said apologetically, “What was all that about?”

In Los Angeles, California, around the same time, another surgeon, Itzhak Fried, inserted the tip of an electrode into the skull of a 16-year-old girl to investigate her severe case of epilepsy. When a low voltage was applied she began to smile. As it increased she started giggling, until finally she fell about in paroxysms of laughter. “You guys are just so funny,” she guffawed at the team of scientists in white lab coats, who began to crack up too because her laughter was contagious.

By poking about in this adolescent girl’s head, neuroscientists had discovered, by mistake, what they called the “laughter center,” a piece of the brain roughly one inch square, in which our sense of humor seems to be located. The 65-year-old woman’s mind revealed what one might term, by extension, the “crying center,” source of all our misery and grief. It turns out these points abut each other in the left-frontal lobe of the brain, and their close proximity provided neuroscientists with a clue as to why laughing and crying are so interconnected.

Whereas Darwin had sought to explain away the confluence in terms of excess nervous energy—“It is probably due to the close similarity of the spasmodic movements caused by these widely different emotions,” he wrote, “that hysteric patients alternately cry and laugh with violence, and that young children sometimes pass suddenly from the one to the other state”—contemporary scientists have found an answer in the very bedrock of the brain. Among the sources of their discovery is a rare disorder known as Pathological Laughter and Crying (PLC), which was first diagnosed in the early twentieth century. The condition illustrates the jumble of the two emotions in startlingly graphic form: patients suffering from PLC suddenly burst into Tourette’s-like fits of giggles or tears.

One well-documented case of PLC is that of 51-year-old landscape gardener, referred to simply as C.B. by his doctor, Antonio Damasio. C.B. suffered a mild stroke in 1999 that damaged both his brainstem and the cerebellum, which neurologists now believe controls the laughter and crying centers, adjusting behavior to the appropriate context. As a result, he’d laugh riotously in response to sad news and sob irrepressibly in response to a joke—or, indeed, in response to anything at all. A laughing fit would sometimes turn into a crying one, but never vice versa, and the patient noted that after a long bout of laughter or crying, he would eventually feel correspondingly jolly or sad. Neuroscientists concluded that “feelings were being produced, consonant with the emotional expression, and in the absence of any appropriate stimulus.” In other words, one can manufacture or summon up an emotion, much as an actor might, by assuming the desired expression. If this is so, one can only imagine the internal pleasures or horrors experienced, while scientists and philosophers preoccupied themselves with the surface of things, by Duchenne’s paralyzed old man.

Christopher Turner is an editor at Cabinet and is currently writing a book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came to America to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.