Derelict Utopias

The Fascists go on holiday

Mark Sanderson

Along the coastline of northern Italy lie a number of distinctive buildings, constructed during the 1930s to function as holiday hostels for the children of industrial workers who were members of the Fascist Party. This kind of building was called a colonia, which translates literally as “colony,” and its purpose was to promote health and fitness in an atmosphere of sun, sea, and regular exercise. The holidaymakers pledged love and allegiance to Mussolini at daily flag-raising ceremonies. For the purposes of propaganda, there was no higher cause than the nurture of Italy’s children and no better vision than boys and girls at orderly play in spectacular settings of modern architecture amid panoramic views. Two futures were on display here: the modernization of a nation together with its future citizens.

The ideology was intended to manage the population through the production of belief, a technique most effective in the young—Mussolini’s most famous slogan, “Credere, Ubbidire, Combattere,”(”Believe, Obey, Fight”) was posted in every classroom. The Opera Nazionale Balilla (founded in 1926) absorbed and unified all various youth groups into a single cohesive entity and offered Balilla Youth between the ages of eight and fourteen after-school activities including sports, gymnastics, military drills with dummy rifles, and excursions to holiday colonies by the sea or in the mountains.

Idyllic spaces and panoramic views coincided with obedience, effort, and militarism. Comradeship was instilled in the Balilla Youth—who played, ate, slept, and marched together—in an attempt to dislodge older allegiances to place, church, and family.[1] Leisure time was being colonized with a view to regulating both consciousness and space.[2] Everyone was to be trained in the ways of Fascism, preparing them for a world of work, war, and mass culture.

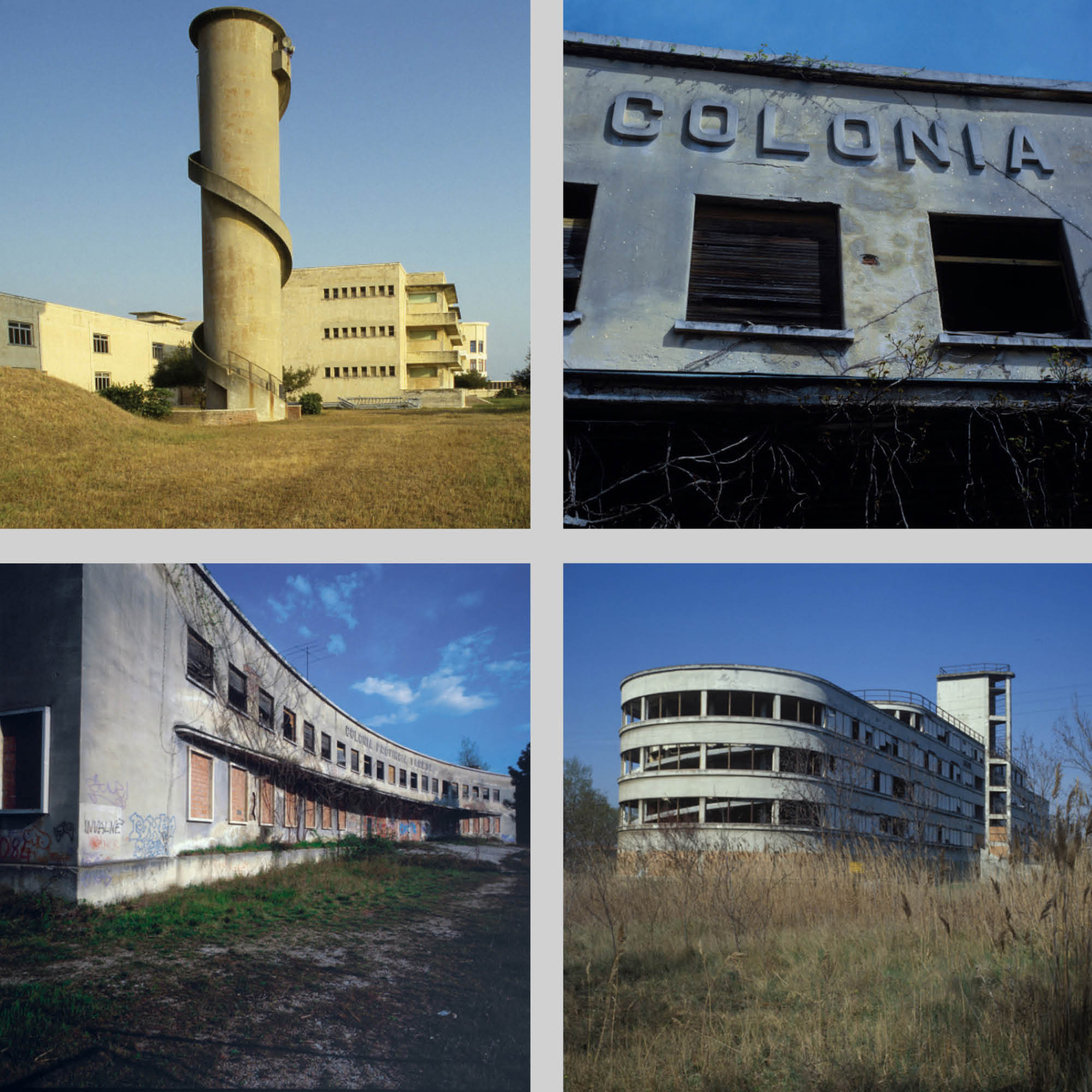

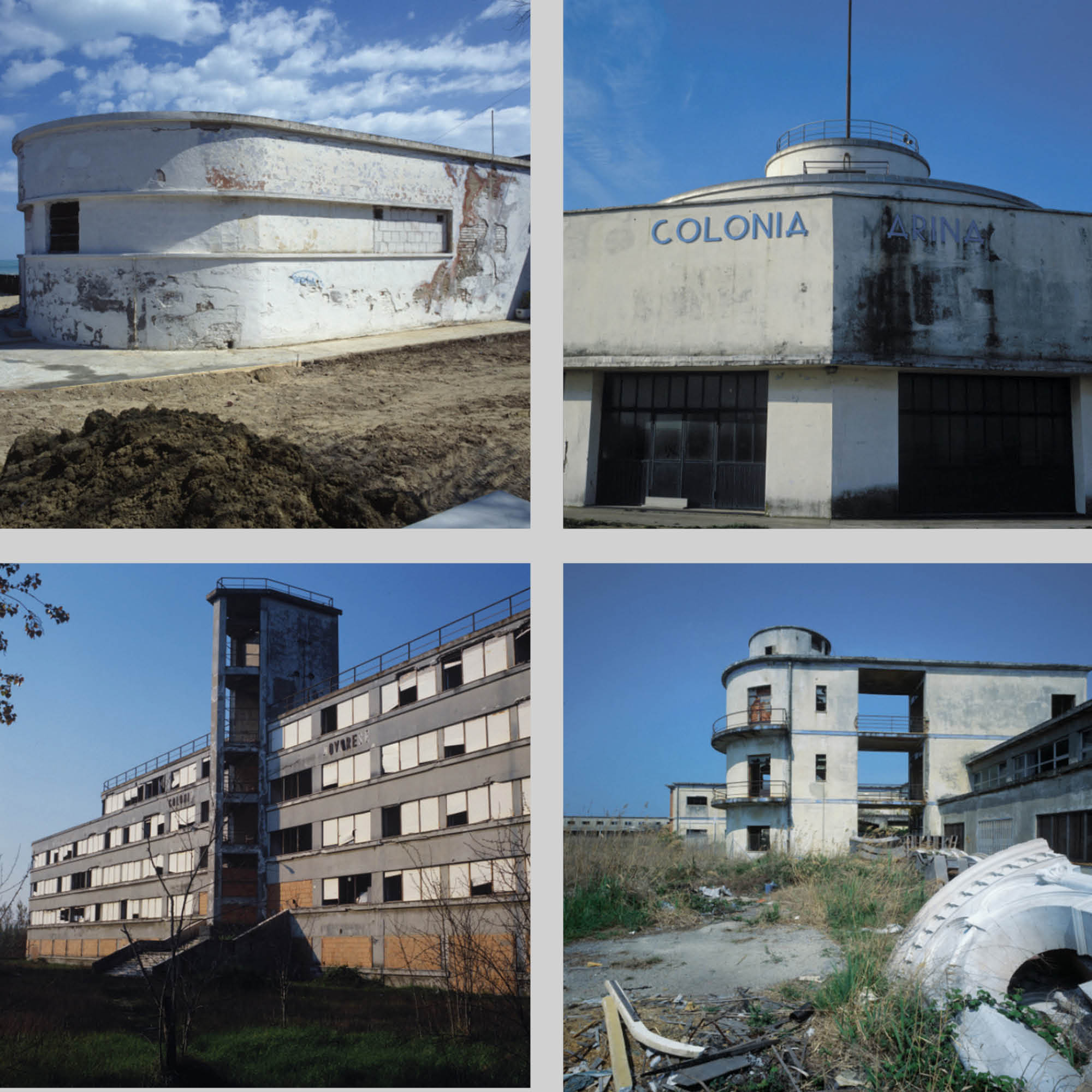

Right column from top: 1) Colonia Costanzo Ciano. 2) Colonia Marina Novarese.

Right column from top: 1) Main hall of Le Navi. 2) Colonia for girls in Tirrenia. Designed by Mario Paniconi and Giulo Pediconi, 1934; grounds now used as a parking lot in summer months.

Some of the colonies were indeed designed to look nautical, through the use of portholes, decks, and streamlined profiles. A colony at Chiavari looks like a thirteen-story conning tower, while the Novarese colony (built in 1934 in just over four months) appears like a cross between a warship and a modern sphinx. “Le Navi,” designed by Clemente Busiri Vici and built in 1932, is the most explicit example of the nautical style to be found in Europe, certainly in the 1930s: four dormitory wings (only two now remain) in the shape of futuristic ships are drawn up on the sand, arranged around a central block that houses offices and a refectory.

Some of the buildings display futurist themes of dynamism either through their streamlined form or through actual dynamic elements that would be activated by the movement of children through them: the Novarese colony had two semi-spiral ramps at each end which acted like turbines as they “flushed” children from the dormitory floors and “siphoned” them up again at the day’s end. The Costanzo Ciano colony features a skeletal bridge carrying two ramps in an X configuration which made a spectacle of the movements of its inmates and ensured an impressive and photogenic scene when used for mass gymnastic displays. Despite its somewhat spectral and austere classicism, typical of late Fascist architecture, the ramp-bridge is also futurist in its triplane-like appearance. It recalls the stage set for the musical number in Gold Diggers of 1933, “Remember My Forgotten Man,” choreographed by Busby Berkeley.[3]

Clearly, the intention was to integrate the theme of play into material form and to signal a distinct function that was essentially without architectural precedent. Another, no less significant, purpose of the colony was to provide a memorable and glamorous experience for the children, one that was in stark contrast to their humdrum everyday existence. The colonies were seen as instruments of modernity, not just through the socialized, robust, and disciplined lifestyle they offered, but also through their power to transform the very nature of their users. As the Italian architect Mario Labò wrote in 1942:

Everything in [the colonies], from their abstract lines and volumes to their ground plans, which trace the itineraries of life in common … everything combines – canteen and washrooms, dormitory and gymnasium—to make up the plastic form and visual image with which, for ever, these children will identify the memories of periods spent in school colonies…. They will be stimulated for the first time to appreciate architectural form seen not just from the outside, but adopted for living within.”[4]

In the process, a new malleable citizen was supposed to emerge, conditioned to the transience of modernity and purged of traditional, vernacular tastes and habits.[5]

The war, which scarred many of these holiday resorts, saw some transformed into temporary barracks, hospitals, and stores; later, scavengers and vandals damaged these too. Whereas old ruins are usually photogenic—full of melancholy and absence—these modern ruins evoke a sense of failure, violence, and indifference. (As Nikolaus Pevsner points out, “Concrete structures, with walls designed to be rendered white, make bad ruins.”[6]) Ironically, many still operate as hostels, though the military-style dormitories have been subdivided for greater privacy. Some of the hostels operate in view of other, now-derelict colonies. In one example, these juxtapositions are combined in the same structure: the “Rosa Maltoni” colony, originally co-owned by rail and postal workers, survives, one half restored, one half disused.

- Camerata, or “room-mate”—the Fascist form of address—derives, like its communist synonym, “comrade,” from the word for room.

- Noel O’Sullivan points out the lasting relevance of Rousseau to activist politics and totalitarian, listing his four main steps to producing patriotic feelings: total politics (no distinctions between the personal and political); total education (with an emphasis on physical exercise to generate competition and emulation); total will (the submerging of all factions in the general will); and total spectacle (making politics into theatre). Noel O’Sullivan, Fascism (London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1983), pp. 93–97.

- It is worth noting that a preoccupation with representations of obedient and well- managed crowds was not only the province of totalitarian regimes.

- Mario Labò, “L’architettura delle colonie marine italiane,” in Mario Labò & Attilio Podesta, Colonie (Milan: Editoriale Domus, 1942), quoted in Fulvio Irace, “Building for a New Era: Health Services in the ’30s,” Domus, no. 659, March 1985, p. 3.

- Anthony Vidler indicates a useful pantheon of twentieth-century thinkers on the topic of the lost nature of dwelling that collects Freud, Heidegger, Bachelard, Dreyfus and Lukacs. Anthony Vidler, The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1992), pp. 7–8.

- Nikolaus Pevsner, “Time and Le Corbusier,” Architectural Review, 125, no. 746 (March 1959), p. 160. In Mark Wigley, White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashioning of Modern Architecture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995), p. xvi.

Mark Sanderson is an architectural photographer and a senior lecturer in Visual Theory at University College for the Creative Arts at Maidstone. His current research is on Italian holiday resorts for children during the Fascist era and his architectural photography has been published in numerous European architecture and interior design magazines.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.