Colors / Scarlet

Our drug of sex and death

Joshua Glenn

“Colors” is a column in which a writer responds to a specific color assigned by the editors of Cabinet.

When paranoid types encounter a word as enduring and pervasive as scarlet (OF, escarlate; It., scarlatto; ON, skarlat; mod. Gr. skarlaton; Serbian, skrlet; etc.), we sit up and take notice.

A signifier used nowadays to refer to a vivid red color inclining to orange or yellow, scarlet is believed to be an alteration of the Persian saqalat (saqirlat, in modern Arabic), meaning a high-quality cloth, usually dyed red. Not just any red, though! In non-industrial societies, flame-red scarlet symbolizes fertility and vitality. Color therapists consider scarlet a vasoconstrictor, arterial stimulant, and renal energizer: they employ it to raise blood pressure, stimulate erections, increase menstruation, and promote libido. And in our popular culture, it’s associated with fallen women (The Scarlet Letter) and those women whom we’d like to see fall (Scarlett O’Hara, Scarlett Johansson, Miss Scarlet from the boardgame “Clue”). It is an intoxicating, maddening hue.

But if scarlet is reminiscent of sex, it’s also reminiscent of death. Since the days of Genghis Khan, poets have marveled at how poppies as scarlet as blood tend to spring up in war-torn meadows; that’s why veterans wear poppies on Memorial Day. And recent archaeological discoveries in the Middle East suggest that scarlet has symbolized death for nearly as long as humans have engaged in symbolic thinking: lumps of ocher found near the 90,000-year-old graves in the Qafzeh Cave in Israel, scholars have claimed, were carefully heated in hearths to yield a scarlet hue, then used in ritual activities related to burying the dead.

Thus in the history of symbolic thought, scarlet has meant both Eros and Thanatos, Sex and Death, the conflicting drives that—according to Freud—govern every aspect of human activity. But what if we’ve got it backwards? What if scarlet caused us to become passionately fixated on transcending ourselves, via merging with others in the act of sex, or by killing and being killed? What if scarlet was a drug—like rhoeadine, the sedative in scarlet poppies used by the god Morpheus, and the Wicked Witch of Oz—first distilled in the ancient Middle East? What if saqalat was not merely a luxury item but an intoxicant that once possessed entire peoples and changed the course of history?

At the risk of being flippant, one might go so far as to suggest that this crackpot theory makes sense of the Old Testament.

Let’s face it: the Pentateuch, or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, authored by Moses himself, tells a far-out story. Skipping over Genesis, the prequel to the main narrative (it’s The Hobbit, if you will, to Moses’ Lord of the Rings), we read in Exodus that the author, an adopted Egyptian prince who came to sympathize with the multiracial community of slaves known as Hebrews, encountered an entity “in flames of fire from within a bush”: If God has a color, that is, it’s flame-red, or scarlet. This unnameable phenomenon (YHWH means “I am who I am”) seems to possess and inflame Moses: when Moses comes down from Mount Sinai after spending 40 days with YHWH, “he was not aware that his face was radiant”(Ex 34:29), and forever after, one reads, he wears a veil when he’s out in public (Ex 34:33–34). What does YHWH want? To shape the Hebrews into a nation unlike other nations, one with no king but YHWH; to reveal Its laws to the Hebrews; and, oddly enough, to instruct the Hebrews in exacting detail on how to erect a tabernacle where It will dwell.

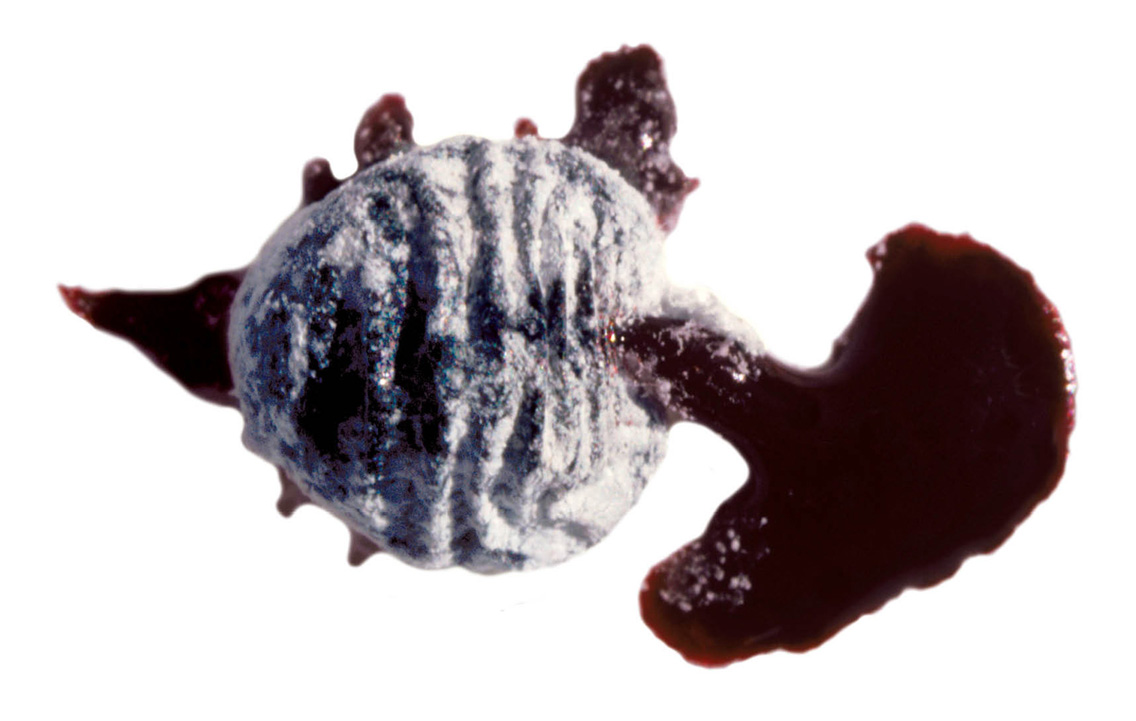

Does this take-me-to-your-leader business put anyone in mind of JHVH-1 (JEHOVAH), the evil, godlike space creature dreamed up by the parodic Church of the SubGenius? No surprise there, because in several important respects YHWH does resemble an extraterrestrial. Like the radioactive alien in the movie Repo Man, YHWH can’t be directly viewed by the Hebrews. It’s kept under lock and key in a protective containment sphere of sorts: the tabernacle. Though the Hebrews have fled into the wilderness with only a few possessions, throughout Exodus YHWH demands from them rare and specific materials for his dwelling place. First and foremost, It orders them to bring offerings of “blue, purple, and scarlet” (Ex 25:4), meaning dyes derived (in the case of blue and purple) from shellfish that swarm in the waters of the northeast Mediterranean, and (in the case of scarlet) from Dactylopius coccus, the cochineal bug, as well as from the various caterpillars and larvae that feed on cochineals.

Now, the scarlet pigment harvested from cochineals and their predators is a compound called carminic acid, which—according to chemical ecologists—functions as a protective substance. So when YHWH tells Moses that It wants Its tabernacle and Its door to be constructed of saqalat, and that furthermore It wants the ark in which It lives to be surrounded by more saqalat (Ex 26:1,36 and 27:16), It is obviously sterilizing Its environment. YHWH goes on to design the vestments of its priests, also of richly dyed cloth, and It forbids anyone “unclean” to enter the tabernacle: any priest who has become unclean through contact with other Hebrews, YHWH insists, must wash himself in scarlet. Leviticus, a book dedicated entirely to the special duties of YHWH’s priests, seems to suggest that scarlet dye was also used by the priests to infect others with what we might call the YHWH virus. In Leviticus 14, for example, we read that YHWH instructed the Levites to use a length of scarlet-dyed cord to sprinkle liquids onto the open sores of any ailing Hebrews. As we shall see, the scarlet cord, which functioned something like a syringe, would become an important symbol for the Hebrews.

There is a great deal more of this kind of thing in Leviticus and also in Numbers, an account of the Hebrews’ nomadic existence in the Middle East following their initial organization at Sinai. But in Numbers, YHWH finally reveals his plan to the Hebrews: they are to invade Canaan. Why? Because Canaan, later called Phoenicia, was a land where the dyeing industry was of central importance to the economy (both names in fact mean “land of purple”); and YHWH must have desired to corner the market. Having possessed the minds and bodies of the Hebrews via his priests’ scarlet cords, YHWH organizes them into a military camp and they march from Sinai as Its conquering army. The only problem is that the Hebrews keep defying YHWH: after thirty-nine years, they still haven’t invaded Canaan, and the old guard of tabernacle insiders is dying off. In Deuteronomy, the final book of the Pentateuch, Moses makes a last-ditch series of speeches urging the Hebrews to remain faithful to YHWH, and then dies himself.

This might have been the end of the history of YHWH on Earth, were it not for the efforts of Joshua, a Hebrew strongman who got his start standing guard outside the first, temporary tent that Moses set up for YHWH. Joshua leads the Hebrews across the Jordan into Canaan, occupies the kingdoms of Og and Sihon, and sends spies into the fortified kingdom of Jericho. At this transitional moment in the Book of Joshua (and the history of mankind), sex and death play a crucial role. Rahab, a prostitute, shelters Joshua’s spies and delivers to them the intel that the Canaanites are terrified of the Hebrews and YHWH. The spies then inform Rahab that when the Hebrews take Jericho, she can spare the lives of her family by hanging something out of her window. Remember what it was? That’s right: a scarlet cord.

Joshua and the Hebrews conquered Jericho and went on to seize control of all the hill country and the Negev, thus gaining control of the area’s dye industries. The next three major books of the Hebrew Bible—Judges, Samuel, and Kings—record Israel’s rise and fall. Judges portrays a kind of anarchist utopia unlike any other nation (i.e., an exploitative monarchy), because it could have only one king: YHWH. Early in Samuel, however, the Israelites bring YHWH’s ark into battle against the Philistines, and it is captured. For twenty years, the ark remains outside its protective tabernacle, and diseases follow it everywhere (1 Sam 5:6). It seems correct to assume that YHWH, unprotected by saqalat, was destroyed at some point during this period. Perhaps this is what Philip K. Dick was getting at in Our Friends from Frolix 8, in which a character announces, “God is dead. They found his carcass in 2019. Floating out in space near Alpha.”

The Hebrews, meanwhile, minds no longer clouded by whatever ego-obliterating substance they’d received via the priests’ scarlet cords, ceased to obey YHWH’s injunction that they should have no other king. Immediately after we learn of the ark’s capture, we read that Samuel, the most distinguished of Israel’s judges, was approached by a committee of Hebrews who demanded, “Now appoint a king to lead us, such as all the other nations have.” Samuel anointed Saul, who proceeded to do what kings everywhere have always done: he built a standing army, invaded other countries, and exploited the populace. By the end of 1st and 2nd Kings, we cannot help but agree with the Hebrew prophets. Alas, Israel became a nation like all the other nations.

So what role does scarlet play in our lives today? We Americans have always enjoyed portraying ourselves as a new Israel, but these days it’s only too apparent that we’re the empire-building Israel about which Isaiah lamented. Not only that, we’re a nation of sex and death addicts, ricocheting from one extreme to another—anorexia/obesity, Puritanism/pornography, sloth/war. Why? Call it an attempt to recapture the annihilating highs and lows experienced thousands of years ago by the Hebrews. Like them, we’re only happy when we’re drinking the scarlet Kool-Aid.

Joshua Glenn is a Boston-based writer and editor, currently for the Boston Globe. In the 1990s, he was editor and publisher of Hermenaut, a philosophy and pop culture journal.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.