Ingestion / Kitchen Confidential

When artists cook

Jeffrey Kastner

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

“Tell me what you eat,” Brillat-Savarin famously wrote at the beginning of his 1825 culinary treatise, The Physiology of Taste, “and I shall tell you what you are.” For the nineteenth-century French epicure, people’s relationship to food held clues not only to their social standing and background, but also to deep-seated aspects of their individual character—their discrimination or indiscipline, their creative energy or lassitude, their wisdom or folly.

One of the centerpieces of Brillat-Savarin’s extended disquisition on cuisine and taste are his series of observations on the concept of “gourmandism.”[1] Defining the term as the “impassioned, considered, and habitual preference for whatever pleases the taste,” Brillat-Savarin draws distinctions between the predestined gourmand and the professional gourmand. Among the eminent categories of the latter he counts the Bankers, the Doctors, the Writers, the Devout, and the Chevaliers and Abbés, each with their own particular appetites and corresponding personality traits.

Curiously, given Brillat-Savarin’s cosmopolitan tendencies, his list does not go on to examine the food personalities of the Artist. For those interested in how such a line of inquiry might look in a more modern context, one place to start is The Museum of Modern Art Artists’ Cookbook.[2] The book—written by Madeleine Conway and Nancy Kirk and published by the museum in 1977 in a simple black-and-white, spiral-bound edition with artist portraits taken by the photographer Blaine Waller—is a combination recipe collection and sociological study, featuring dishes concocted by (and occasionally quite intimate insights into the lives of) thirty leading artists of the day, ranging from the legendary (Bearden, Dali, de Kooning, Lichtenstein, Motherwell) to the lesser-known (Richard Anuszkiewicz, Allan d’Arcangelo, Richard Lindner, Ernest Trova). What follows are brief excerpts from some of the artists’ entries, along with a few of their more idiosyncratic recipes.[3]

Louise Bourgeois

“I was told as a child in France that cooking is the way to a man’s heart. Today I know that the notion is absurd, but I believed it for a very long time. My mother was in delicate health and could not cope with long hours of work in the kitchen. To please her I took on the responsibility of seeing to it that my father had dinner. It wasn’t easy. He often came home very late. I waited for hours to make sure the food stayed hot and fresh—and I became expert at just that. When my father appeared and wanted a steak, I cooked it for him. In those days a man had the right to have his food ready for him at all times. During my student years I did not cook at all. The memory of those many wasted hours lingered. I subsisted on yogurt, honey, and pumpernickel bread. I still eat the same foods today.”

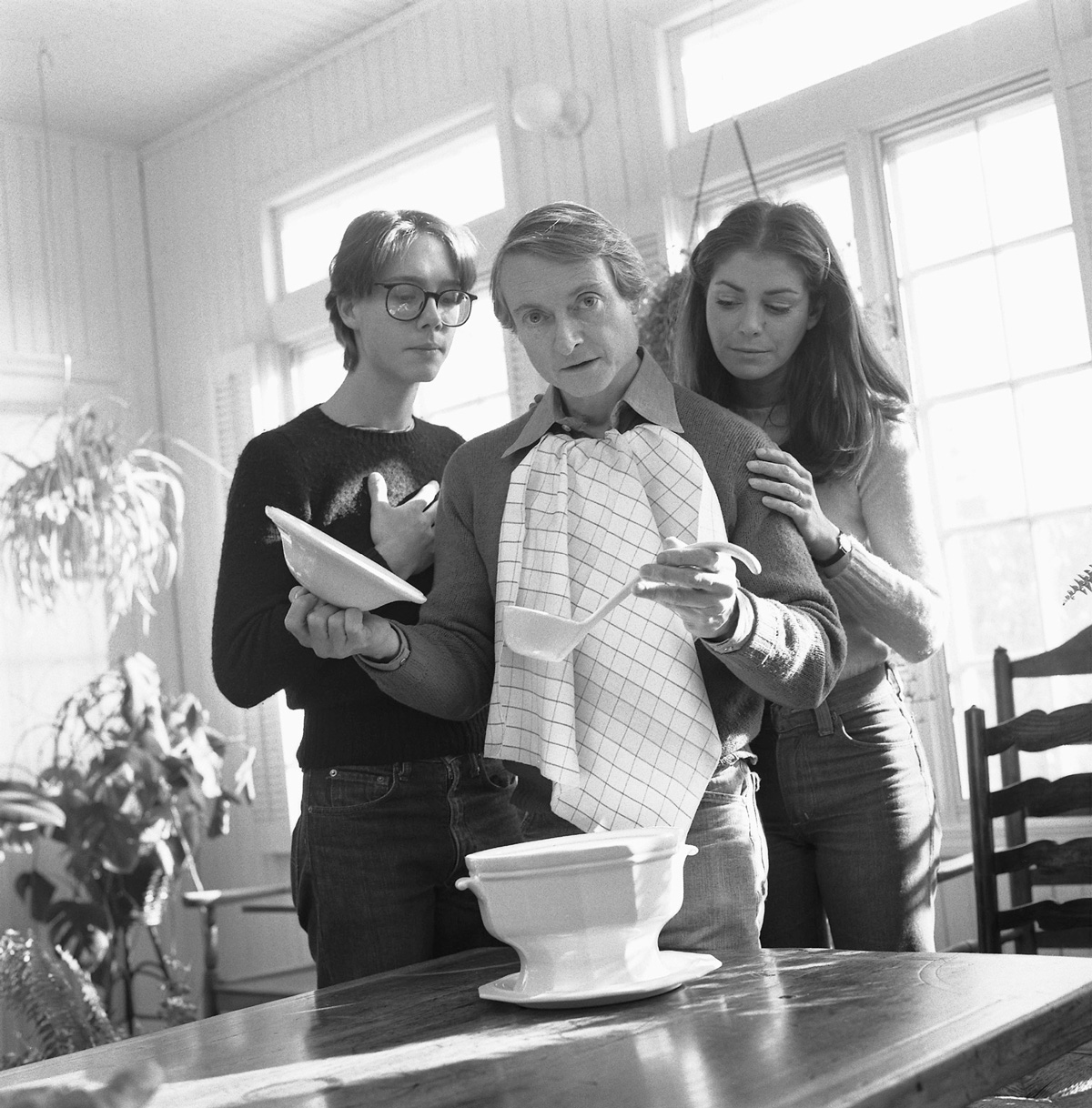

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Christo and Jeanne-Claude are very energetic and always busy—too busy, really, to think about food or to eat regular meals. Jeanne-Claude opens her oven and says, “I use my oven for storage space for my dishes. I never cook in it. It stays clean and beautiful.”

Christo adds, “We don’t eat, you know. Food is very unimportant. I don’t have time for it. We eat well only once a day—in the evening. Sometimes at midnight, sometimes at 9 o’clock.” ... Jeanne-Claude laughs, “What we say is not really true. We love to eat, but we don’t think about it. I have another oven downstairs! If I want to, I’m a great cook!”

Salvador Dali

Dali has designed and illustrated several books, including his own cookbook. His ideas on food are both exotic and classic. His book contains some recipes from Lasserre, Maxim’s, Tour d’Argent, and the Buffet de la Gare de Lyon. The recipes range from quail eggs with caviar to roast beef.

Dali has painted food symbolically. “The bread and wine of the Last Supper are mystical to everyone. They are Eucharistic symbols. Cannibalism is also a symbol. The praying mantis mates and then eats its mate. That is my last word on food.”

Helen Frankenthaler

“I’m adventurous, but I diet a lot to make my eating fun,” says Helen. “I don’t want to be fat. I don’t work well when I’m heavy, and I lose my self-esteem. I have more energy when I eat in a healthy way. My usual regime is no fat, no salt, no butter, no sugar, no bread, no cream, but homemade skim-milk yogurt. I don’t enjoy hard liquor or soft drinks. Processed cheese, kosher dill pickles, peanut butter, cheap sardines, and bologna—junk food; these are the things that I periodically crave and give in to. I keep a very healthy ice box so I’m not tempted, because if Sara Lee is in the freezer and I know she’s there, I’m destroyed.”

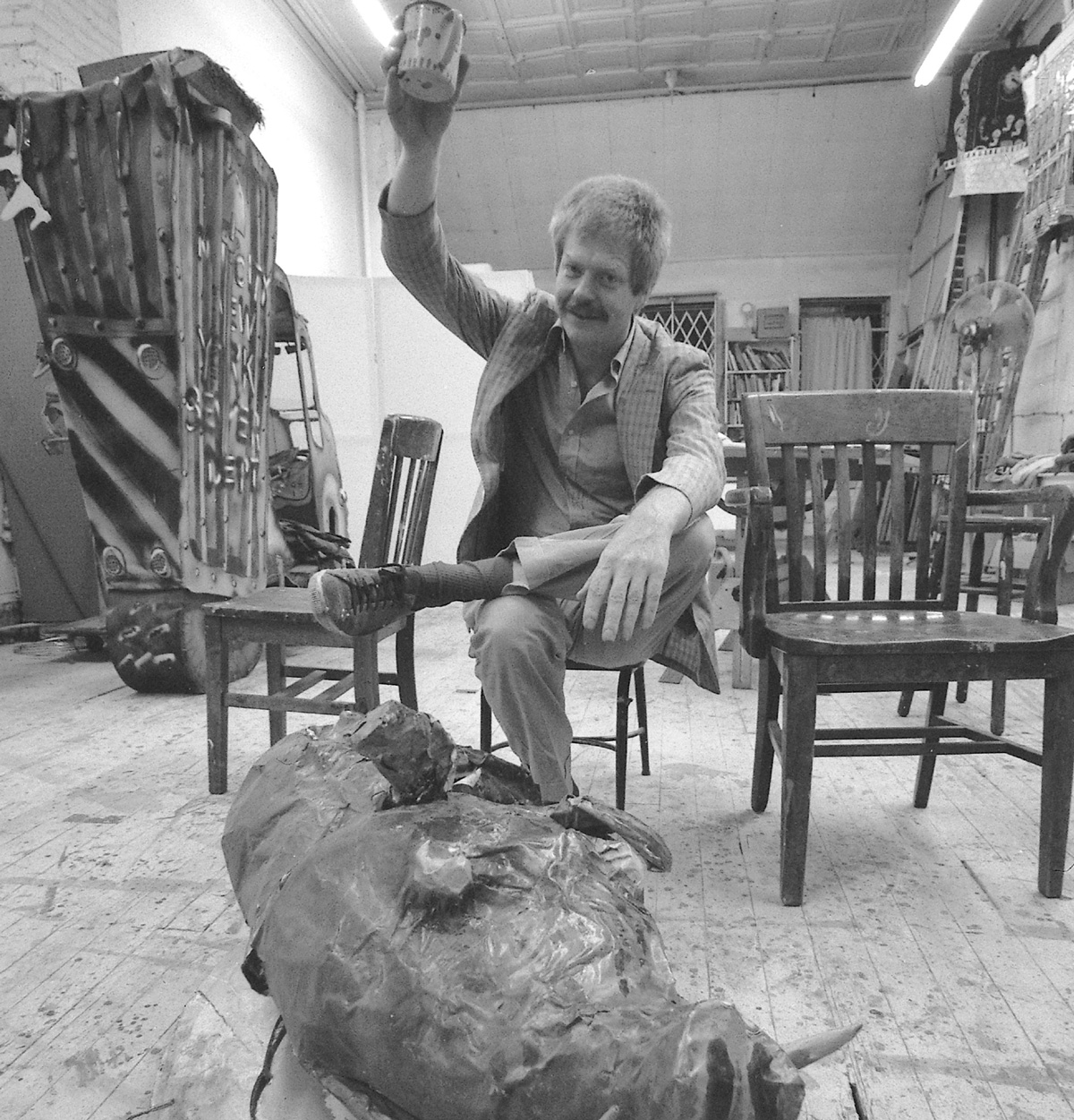

Red Grooms

Red Grooms sits down on a chair too small for his legs, sips a gin and tonic from a cup marked “cup,” and chews a chocolate Mallomar. He bought these treats on impulse because he can’t plan his snacks in advance. In the middle of the floor, on a large platter, rests a dark boar’s head made of papier mâché, an apple in its teeth. At one “performance,” he stuffed pounds of sliced bologna and steaming dry ice into the gaping hole in its neck. He then made sandwiches for the audience. Red is sure the image is what he wanted, but he is not sure of its meaning.

Robert Indiana

There is a decidedly serious aspect to Robert Indiana’s feeling about food which is best exemplified by his EAT/DIE paintings. “EAT and DIE are really two sides of a coin. Eat was the last word my mother said to me before she died. I was in the Air Force in Alaska when she became seriously ill. Somehow she held on until I got home. When I came in the door she could hardly speak but what she was trying to say was, ‘Did you have something to eat?’ Five minutes later she was gone.”

Willem De Kooning

After more than fifty years, Willem de Kooning still marvels at his adopted country, America, and remembers his early years in Holland. “It was hard to overeat when I was a boy because when you had dinner, it was always brown beans. We were poor. When I came to America I had never seen so much food in my life! I came to America as a stowaway. When I was discovered among the pipes, I became a kind of cabin boy and washed the decks. I got off when we landed in Boston and took a train to New York. I went right to Wall Street. I recognized from the silent movies where the Stock Exchange was. ... My brother Koos came from Holland for a visit. He made me Dutch breakfast, which is roast beef and fried eggs, and he made a Dutch dinner especially for me—brown beans.”

Dutch Breakfast

(Serves 2)

2 thick slices white bread, buttered

2 slices roast beef or boiled ham

2 eggs, fried

Salt and pepper

Place slices of meat on bread and top with one fried egg each. Salt and pepper to taste.

Roy Lichtenstein

My favorite recipe? Primordial Soup. It is the atmosphere that may have generated life on earth.

Primordial Soup

8 cc hydrogen

5 cc ammonia

6 cc methane

10 cc water vapor

Dash of nitrogen

Heaping tablespoon carbon monoxide

Mix well in blender. Faulty connections should supply electrical sparks. Ultraviolet light should help. Wait for complex molecules to develop. Pour mixture into two-quart enamel saucepan and simmer over low heat. Soon, in geological time, amino acids will synthesize, become protein, and begin self replications. When two quarts have developed, remove from heat.

Note; Garnish with parsley. Serve with lemon slices on the side.

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol doesn’t eat anything out of a can anymore. For years, when he cooked for himself, it was Heinz or Campbell’s tomato soup and a ham sandwich. He also lived on candy, chocolate, and “anything with red dye #2 in it.” Now, though he still loves junk food, McDonald’s hamburgers and French fries are something “you just dream for.”

The emphasis is on health, staying thin and eating “simple American food, nothing complicated, no salt or butter.” In fact, he says, “I like to go to bad restaurants, because then I don’t have to eat. Airplane food is the best food—it’s simple, they throw it away so quickly and it’s so bad you don’t have to eat it.”

Campbell’s Milk of Tomato Soup

A 10 3/4-ounce can Campbell’s condensed tomato soup

2 cans milk

In a saucepan bring soup and two cans milk to boil; stir. Serve.

- The word gourmand is typically understood to refer to culinary overindulgence, but Brillat-Savarin takes pains to distance the term as he uses it from its associations with gluttony. For him, the meaning is closer to what we think of as a gourmet.

- Cabinet first became aware of the cookbook via a project by artist Allison Wiese in “Phantom Captain: Art and Crowdsourcing,” a 2006 exhibition at New York’s Apex Art, curated by Andrea Grover.

- The editorial comments that occasionally frame the artist’s direct quotes were presumably written by either Conway or Kirk or both—the book, long out of print, includes no specific credits for the various introductory texts.

Jeffrey Kastner is a Brooklyn-based writer and senior editor of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.