Talking with the Volcanoes

Devotion to the twin peaks

Jesse Lerner

Scattered throughout the Mexican state of Puebla, in out-of-the-way towns like Tecali de Herrera, Tepeaca, and Tecamachalco, are a series of sixteenth-century Franciscan convents, now largely abandoned and in varying states of disrepair. These massive structures are most remarkable for the exceptional syncretic murals that they house, the work of indigenous artists struggling with and adapting unfamiliar European subject matter in the aftermath of the Spanish Conquest. The resulting images embody the fusion of two religious traditions. Jaguars, eagles, and other fauna with divine connotations in the Mesoamerican mind bear witness to the Annunciation; representational tropes borrowed from the pre-Cortesian codices find their way into biblical scenes. Old World landscapes transform when rendered by artists unfamiliar with the originals they sought to represent. These exquisite paintings are vivid testament to a process of cultural mestizaje, the fusion of European and Mesoamerican systems of belief and representation. But this mestizaje is not simply a thing of the past, the product of Iberia’s violent subjugation of the pre-Columbian world five hundred years ago. The process of cultural hybridization continues today, and diverse expressions of the union of the two distinct belief systems continue to live, evolve, and thrive in these very same places. The photographer Everardo Rivera has documented one such contemporary expression, in which the participants, drawing on Aztec and Catholic beliefs, not only worship but also converse with the volcanoes in whose shadows they live.

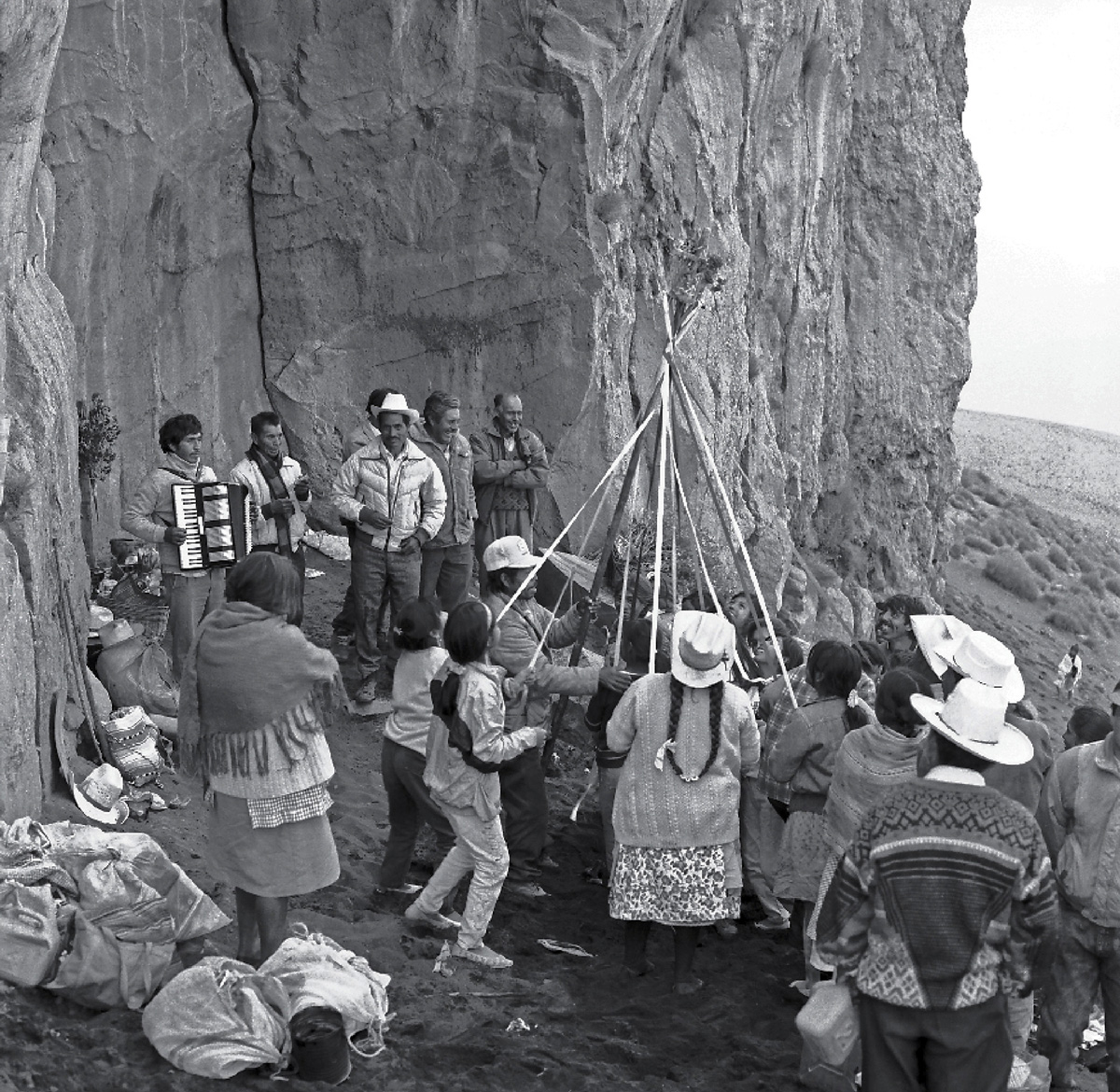

Not far from these Franciscan ruins, on the edge of the central valley of Mexico, the Catholicism imposed with the Conquest coexists with pre-Columbian rites of devotion to the twin peaks, a religious practice that seamlessly joins together Aztec and Christian elements. In these Nahuatl-speaking agricultural villages at the base of the volcanoes Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatepetl, certain residents are believed to be chosen by the mountains to take on special ritual obligations. To some, the calling comes in their sleep, by way of dreams; others are designated in a more dramatic way when a lightning bolt lands at their doorstep. Depending on the region, these practitioners are called tiemperos, aguadores, conocedores del tiempo, or trabajadores temporaleños. All the chosen individuals speak with the volcanoes in their dreams and employ this privileged line of communication to ensure adequate rains for the crops, placate the mountain divinities with offerings, and heal the sick. In spite of centuries of clerical condemnation and, at times, active repression, each year at the beginning of May the chosen practitioners climb the two mountains bearing foodstuffs, cooking utensils, and religious paraphernalia, well past the point where professional climbers will only proceed with specialized equipment. There they prepare a turkey in mole sauce, a regional delicacy. After a picnic, music, and a ritual offering, they descend back to their villages carrying boulders that, when placed in their fields, will help ensure adequate rains for the rest of the year.

In his extended photo-essay, Rivera has documented these rituals of climatic control as practiced by the inhabitants of Xalitzintla, a small town not far from his home in the city of Puebla. The photographs reflect a level of trust and intimacy all the more remarkable given the secrecy that is the result of the Church’s efforts at suppression. The images also clearly reveal the syncretism of the observances: Catholic elements, such as the bell, votive candles, and crucifixes appear side by side with clay figurines of the Aztec rain god, Tlaloc, at ritual sites that have been in use for centuries. The setting is a liminal one, high among the clouds, between the profane spaces of everyday life below and the divine realm above. The tiemperos function on this threshold as intermediaries, between the material and the spiritual, between earth and heaven.

In centuries of Mexican art, the two volcanoes, Popocatepetl and Iztaccíhuatl, have functioned as national symbols. From Jesús Helguerra’s popular calendar art, with its kitsch, hyper-Mexican renditions of the Aztec myth of the volcanoes for the masses, to José María Velasco’s meticulous academic landscapes of the valley of Mexico and its changing light, these two peaks are recurrent elements in the nationalist visual vocabulary. Beyond their religious significance, the tiemperos likewise take the volcanoes as a national metaphor. In December 1994, for example, in the aftermath of the Zapatista insurrection and a series of assassinations of high-level political leaders, and on the eve of a devastating currency devaluation, Popocatepetl began to smoke, rumble, and spew lava, leading local authorities to design emergency evacuation plans. The tiemperos diagnosed this volcanic activity as a symptom of the national crisis. They and the communities whom they serve did not participate in the state-sponsored evacuation drills. They contend that when their settlement is truly in danger of becoming a modern-day Pompeii, buried in lava and ash, the volcano will tell them.

Jesse Lerner is a filmmaker and writer based in Mexico City. His book on crime and photography in Mexico City of the 1920s and 1930s, The Shock of Modernity, was published by Turner/INAH in 2007.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.