Mountain and Fog

Kant and the Nazi sublime

Nina Power

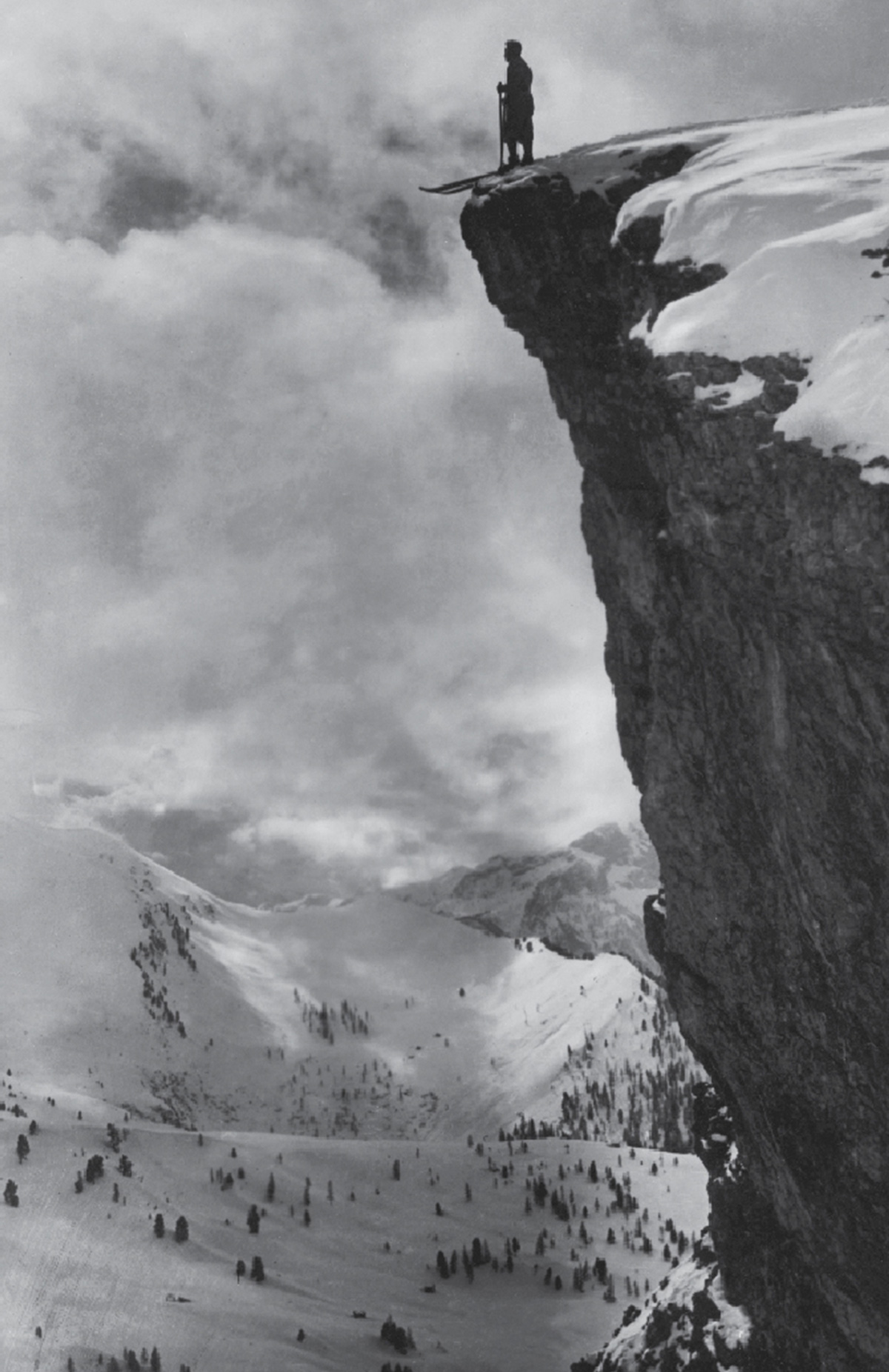

Although Immanuel Kant, happily ensconced in Königsberg, probably never saw a mountain, he is more than happy to discuss them in his masterpiece of aesthetic theory, The Critique of Judgment, published in 1790. Given the Romantic veneration after Kant of the “sublime nature” of peaks in poetry, painting, and later, German cinema—between Caspar David Friedrich and Leni Riefenstahl—what he says about them might surprise us. His message is, above all, a warning: do not conflate the power of nature with the power of your own mind. An encounter with the mountain, the raging sea, Arctic wastes, might make you feel like a hero, but what it should really point to is a respect for our fragile and profoundly human moral vocation.

It is precisely this moderate Kantian lesson that the pre-Nazi Bergfilm (“mountain film”) made by Arnold Fanck, Leni Riefenstahl, and others in the 1920s fail to heed. In these films, those who dare to tackle the mountain are young, beautiful, and heroic. They are also impulsive and completely irresponsible. It is this combination of physical flawlessness and the blind celebration of danger that leads Siegfried Kracauer, in his 1947 From Caligari to Hitler, to claim that these mountain films, so beloved of the young Hitler, were “rooted in a mentality kindred to Nazi spirit”. There is, on the one hand, a Kantian sublime, a moment of mental agitation succeeded by the revelation of a shared moral capacity, and, on the other, there is the Nazi sublime, a supremely volatile cocktail of the fantastic and the sentimental. As François Lyotard puts it in his essay “The Sublime and the Avant-Garde” on Barnett Newman, “The aesthetics of the sublime, … converted into a politics of myth, was able to come and build its architectures of human ‘formations’ on the Zeppelin Feld in Nürnberg.”

Amid the coalescence of highly advanced cinematic technique with thunderously banal emotional content in the Bergfilm, we should not blame the mountain itself, for it is an unwilling participant in a dangerous game of aesthetic and moral equivocation. Much of the dynamism of the mountain films and the later Nazi propaganda films depends upon the expert manipulation of contrasts, both visual and sonic: light and shadow, earth and sky, man and heavens, the solitary face and the mass rally, human beauty and inanimate nature, music and blackness. But these pairs are not simply presented as opposites. There is a third element that best characterizes the fascist aesthetic, and that is obfuscation.

What hovers at the limits of these stark contrasts is the relentless presence of mist, cloud, fog, steam, shimmering light, dust, haze, the fluttering of flags—anything to prevent the emergence of reflexivity or critical resolution. Cinematic fascism, or rather the cinematic attempt to aestheticize fascism, precisely depends upon occult confusion and the attempt to make impossible any clarity of thought. We see this everywhere: from the miasma out of which Hitler’s plane descends in Triumph of the Will, to the mist that floats across the Olympic rings at the beginning of Olympia; from the steam rising from the cooking in the army barracks, to the trails left by the torch-bearing skiers in the mountain films. Mountain air is not clean and pure, but heady and disorienting.

In contrast to the Soviet cinematic output of the 1920s, with its relentless attention to process, production, and the tracking of people and machines from one point to another, Fanck’s and Riefenstahl’s films present scenes that simply appear. The crowds waiting to greet Hitler are simply present, just as the mountain is simply present (recall Mallory’s famous response when asked why he wanted to climb Everest: “because it is there”). The ordered human masses of Triumph of the Will are thus prefigured in the opaque “thereness” of the shapeless physical masses of the mountain films. One can speak here of a certain frozen style. Even in the midst of exertion, movement, vitality, and dynamism, there is a distinct stillness both in the representations of nature and in the statuesque bodies of the gymnasts and blond boys listening impassively to Hitler’s speeches in Triumph of the Will. The element of obfuscation—this opaque, cloudy dizziness of unreason that smears the edges of perception—furthermore prevents any attempt to track origins or consequences. There is no moment at which the characters of the Bergfilm or the figures in Triumph of the Will can reach a point of decision because all possible self-assertion has already been filled in by the combination of post-Romantic mantras (brotherhood, loyalty, strength, the fatherland) and metaphysical haze—the light-headedness of one who climbs a mountain in a snowstorm to escape the urban quotidian drudgery of the “valley-pigs,” those homogeneous city-dwellers who could not possibly comprehend the majesty of the “holy” berg.

The commitment to presenting extremes in a smothered way, to promoting lofty sentiments in the name of an elitist heroism—love, destiny, infatuation, all terms that are as stirring as they are vague—is the ultimate aim of the mountain film. These films summon a universe that is at once meaningful, intensive, and occasionally beautiful—a kind of religion without transcendence, whose earthly yet mysterious skies and clouds drift through one’s heart with a sublime significance. Turning to Kant’s separation of the beautiful and the sublime, one finds the following point:

The beautiful in nature is a question of the form of object, and this consists in limitation, whereas the sublime is to be found in an object even devoid of form, so far as it immediately involves, or else by its presence provokes, a representation of limitlessness, yet with a superadded thought of its totality.

The capture of the beautiful in nature (whether it be the rushing rivers and snowy peaks of the mountain films or the bodies of the divers in Olympia) is a representation of pure form, and it astonishes before one has a chance to distance oneself from such intense immediacy. The sublimity of the mountain, on the other hand, symbolizes both the limitlessness of ambition and the impossible desire to make such an ambition all-consuming. It is no coincidence that the “Holy Mountain” of Fanck’s 1926 film causes the death of all three lead characters (even if we don’t see Riefenstahl’s character die at the end of the film, it is her death mask that fills the first frame). But the proto-Nazi sublime deliberately mistakes the subjective judgment with the object itself. Kant, on the other hand, takes care to guard against this temptation:

True sublimity must be sought only in the mind of the judging subject, and not in the object of nature that occasions this attitude by the estimate formed of it. Who would apply the term “sublime” even to shapeless mountain masses towering one above the other in wild disorder, with their pyramids of ice, or to the dark tempestuous ocean, or such like things?

A better description of the conception of the sublime at work in the Bergfilm could not be found anywhere. It is precisely in these films that an idea of the sublime is directly applied to those “shapeless mountain masses”: the vapid enthusiasm of the young mountain climbers and their willingness, indeed desire, to die rather than stay in the world of the everyday, is the ominous precursor of a generation prepared to sacrifice itself in the name of an opaque all-consuming passion. Kant continues his warning:

Though the irresistibility of nature’s might makes us, considered as natural beings, recognize our physical impotence, it reveals in us at the same time an ability to judge ourselves independent of nature, and reveals in us a superiority over nature that is the basis of a self-preservation quite different in kind from the one that can be assailed and endangered by nature outside us. This keeps the humanity in our person from being degraded.

We might question Kant’s claims for our “superiority” over nature, but it is clear that the sublime in this instance involves a moment of judgment, a reflective and shared capacity to mark our rational distance from the world outside. Whereas Kant’s sublime reinforces the subtle self-rule of reason, however, the Nazi sublime simply conflates nature and the external object with the subject. The healthy mountain-climbing youth comes to represent a paradigm of beauty and determination that deliberately excludes vast swathes of humanity.

Siegfried Kracauer notes that in the Bergfilm “immaturity and mountain enthusiasm were one.” This association of youth and the mountain is crucial. The mountain is the place to test one’s strength, to reach as far up into the clouds as possible. Nature, and the mountain in particular, is simultaneously the object of youth-worship, the place of non-religious but nevertheless mystical destiny, and key symbol of the sublimation of sexual desire. For later filmmakers such as Werner Herzog, who in many ways works with the same themes as the Bergfilm, the crucial point of separation comes with undoing the idea that nature has a privileged relation to youth. In fact, if anything, for Herzog, it has a privileged relation to madness, the outsider, the renegade. Nature for Herzog is also profoundly indifferent to human concerns, and reveals little of one’s “destiny” or role. He states: “I believe the common character of the universe is not harmony, but hostility, chaos, and murder.”

For the directors of the Bergfilm, however, it is the combination of physical exertion and stillness in the face of natural beauty that calms and attempts to discipline, even if it cannot quite entirely eradicate, sexual desire. At every point in The Holy Mountain, in particular, where lust threatens to explode into language or physicality, the characters go skiing or climb mountains, pausing occasionally to admire an Alpine view. Mountain-climbing is pure sublimation that removes sex in order to raise an increasingly fit youth to ever greater emotional and patriotic heights.

When Hitler in Mein Kampf surveys the contemporary cultural world, one of his main complaints, aside from its “regression” and “degeneracy,” as we might expect, is of the lack of cultural access permitted to the youth: “It was a sad sign of inner decay that the youth could no longer be ‘sent’ into most of these so-called ‘abodes of art’—a fact that was admitted with shameless frankness by a general display of the penny-arcade warning: ‘Young people are not admitted!’” What, Hitler asks, would the great dramatists have had to say about the exclusion of the young from art galleries and theaters? “How Schiller would have flared up, how Goethe would have turned away in indignation!” If the theaters and art galleries don’t want the youth, then the mountains will welcome them with open (if occasionally deadly) arms. They certainly pleased the most infamous of Goethe’s teen suicides, Werther, whose immature sorrows and nature-worship precisely circulate around mountains:

Stupendous mountains encompassed me, abysses yawned at my feet, and cataracts fell headlong down before me; impetuous rivers rolled through the plain, and rocks and mountains resounded from afar. In the depths of the earth I saw innumerable powers in motion, and multiplying to infinity; whilst upon its surface, and beneath the heavens, there teemed ten thousand varieties of living creatures.

And, perhaps more revealingly, “As I contemplated the mountains which lay stretched out before me, I thought how often they had been the object of my dearest desires.” The fusion of the Nazi sublime with this strand of youthful “mountain-lust” captures a devastatingly strong irrationality that feeds directly into those later aesthetic manifestations of fascism that no longer need to rely upon mountain imagery directly. What we learn above all from the Bergfilm is the supremely dangerous power of lightheadedness.

Nina Power is a philosophy lecturer at Roehampton University, London. She is the co-editor of Alain Badiou’s writings on Samuel Beckett (Clinamen Press, 2003) and has published numerous articles on contemporary politics and philosophy. She is currently writing a book on feminism and capitalism for the newly founded Zero Books, and she is also a member of the film collective Kino Fist.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.