Colors / Puce

A flea in your ear

Barry Sanders

“Colors” is a column in which a writer responds to a specific color assigned by the editors of Cabinet.

Some French wag in the seventeenth century played a colossal joke on the world, creating a color that everyone has heard of but, over three hundred years later, very few can define. The color is puce. But that’s not the joke. It’s that puce turns out to be the most decidedly sexual and most violent color in the paint box. Puce is about plotting. Puce is about villainy. And it is not just about simple murder, but the emotionally charged and deranged murder usually associated with love—with jealous, overheated love. Think twice about using puce, or at least heed its creepy history.

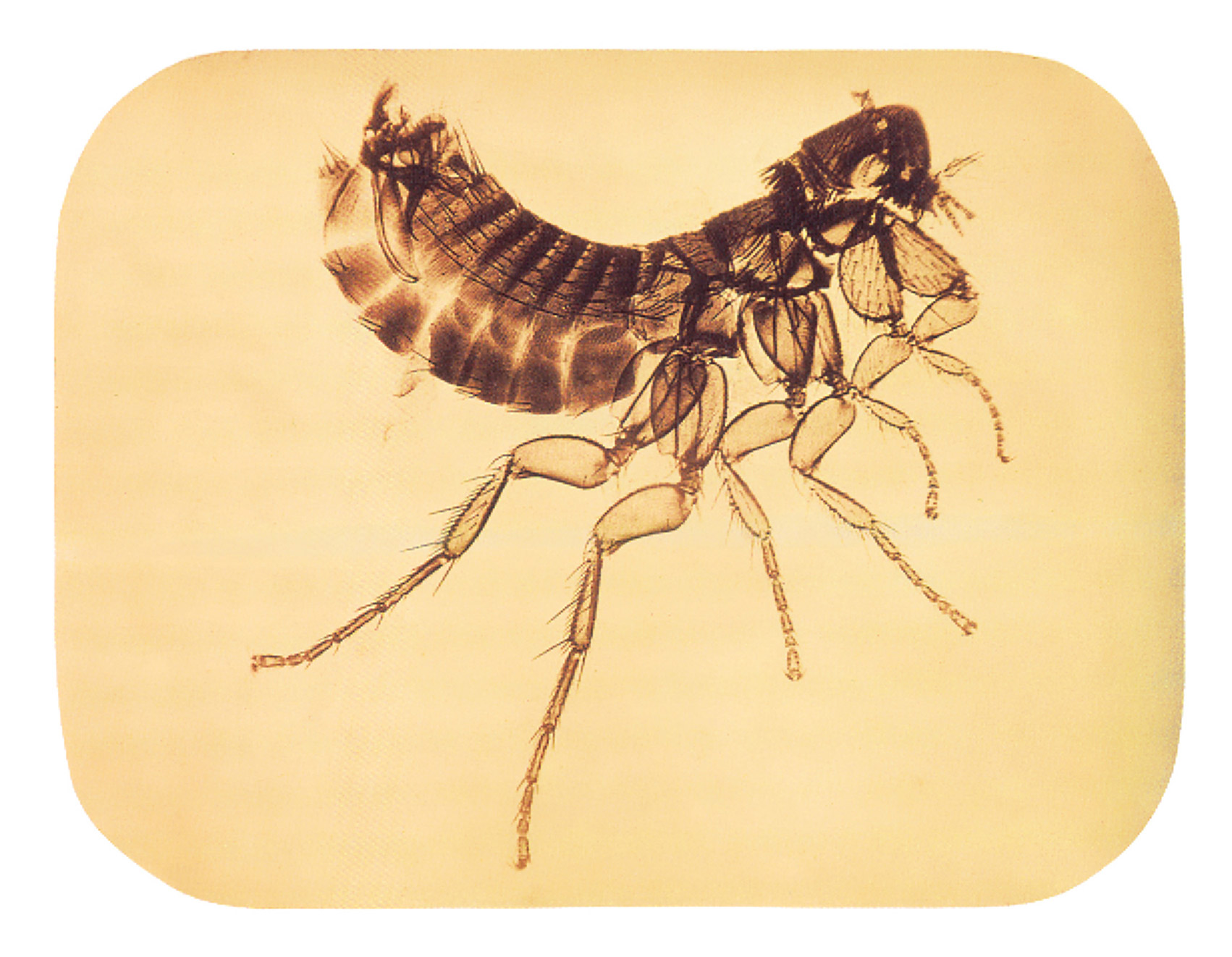

The first but by no means strangest fact about puce is that it owes its existence to one of the tiniest animals in the kingdom, the flea—in Latin, pulic or pulex, or more descriptively, pulex irritans. In Old French, flea is pulce, which by the time of the Renaissance becomes puce. Which prompts the question: how did we get from the loathly flea to the lovely puce? The answer is a surprising one—especially in the usually predictable world of the color wheel.

Don’t expect to find the answer in the Oxford English Dictionary, for it offers only the following thoroughly confusing definition: “Of a flea-color; purple brown, or brownish purple.” Does the OED deliberately deceive? Puce is not flea-color—that would render the color black. And black is far from either brown or purple. The supreme arbiter of the English language only perpetuates the mystery.

Even putting aside the differences of color, we have to ask: Why would anyone memorialize such a nasty, outrageously useless pest? Surely, there must be something other than perversity going on here. Camel brown and dove gray, colors that take their name from respectable animals, we can understand. But a flea seems out of the question. After all, fleas have been responsible over the centuries for millions of deaths. The flea is the plague; the flea is the Black Death. Moreover, everyone knows the flea’s intimacy with that dreaded rodent, the rat—a relationship just too, too disgusting for most people.

And yet the flea has another side, this one outlandishly sexual. It’s what appealed, I am certain, to our anonymous French wag. The flea took on its sexual identity from a string of suggestive cognates with puce, like pucelle, “maiden” (and in certain contexts, “slut”); pucelage, “maidenhead”; and depuceler, “to deflower.” In addition, the French eroticize the flea in a phrase popular since the fourteenth century, “avoir la puce à l’oreille” (“to have a flea in one’s ear”), meaning that one harbors a libidinous urge, “a sexual itch.” Say the word puce today, and a Frenchman will either titter or offer a knowing wink.

As far back as antiquity, that little black speck starred in some of the most elaborate metaphors of love, beginning with a volume of poems entitled Carmen de Pulice, “Songs of the Flea,” which some historians attribute to Catullus, and others to Ovid. But while the flea’s sexual career blossomed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries with a rash of erotic flea poetry, it really took hold in late sixteenth-century France after a celebrated court scandal. A flea, it seems, can fell a nation.

The events in question unfolded in the most innocent way. One particular evening in the summer of 1579, Monsieur Étienne Pasquier, a lawyer and distinguished man of letters, made a call on Madame Madeleine Des-Roches at Poitiers, and, to his surprise, noticed a flea on the bosom of her daughter, Mademoiselle Catherine. Pasquier, along with the other assembled gentlemen, showed special interest in the flea’s audacity but delighted even more in the privileged spot the flea had chosen for itself. A great commotion ensued, the men huddling in the corner to plot a course of action: should one of them pluck the flea, so to speak, or should they ignore the tiny parasite altogether?

No, they decided, they could not completely sidestep the flea and the virgin. And so, as distinguished men of letters, they decided to commemorate the event by composing poems about the jet-black flea on Mademoiselle’s snow-white bosom. With great fanfare, they published their cycle of some fifty poems, in 1582, giving it the very direct but nonetheless provocative title, La Puce de Madame Des-Roches. In an attempt to dazzle Mademoiselle Catherine with the far-fetched reaches of his poetic imagination, the rather portly Pasquier imagined himself as a flea—more accurately, perhaps, as a pest—so as to better play the lover: “If only God permitted me / I’d myself become a flea. / I’d take flight immediately / To the best spot on your neck, / or else, in sweet larceny, / I would suck upon your breast, / or else, slowly, step by step, / I would still farther down, / and with a wanton muzzle / I’d commit flea idolatry, /nipping I will not say what, / which I love far more than myself.”

Lacking in restraint (and good taste), Pasquier grew even more tedious as he brought his love to a climax of sorts, falling back on that overused French phrase: “Oh flea . . . / Thanks to you, Madame / Is aroused for me. / For me she is aroused / And has a flea in her ear.” We have no record of Catherine’s or her mother’s reaction to Pasquier’s rugged doggerel. Critics, too, chose not to comment.

Most of the assembled gentlemen wanted to kill the flea, but stopped themselves. Which takes us to the very dark heart of the joke. A flea’s color does not change after it bites an animal or a person: the flea, both pre- and post-bite, retains its jet-black appearance. Some poets boasted that they could notice a change in the size of a flea after it had taken a bite, the image of an engorged flea designed to bolster the insect as sexual symbol. But to discover if a flea has blood inside it or not—in this case, Mademoiselle Catherine’s elegant and refined blood—requires one thing only: a person must flatten it.

That’s what the men at the Des-Roches court all knew: the temptation to kill the flea is always present, always a reality. Confronted with the flea, each one of us, even the most normal-seeming person, just cannot wait to get that irritating pest between our nails—especially after it has bitten an arm or leg—and slowly, deliberately squeeze until we hear that tell-tale pop. Call it what you want, but that death squeeze constitutes an act of revenge. And it’s that trace left behind on your fingertips, the reddish stain, that our seventeenth-century French practical joker memorialized as “la couleur puce.”

And thus the catch—the real joke. We can only enjoy the color puce, only experience it first hand, by killing. In order to spill our own artistic guts, we must first spill the flea’s. And given its sexual connotations—recall pucelage and “maidenhead”—“popping the flea” reverberates with sexual innuendo, specifically with breaking the hymen. Puce is love’s stain. Hence none of those respectable gentlemen around Catherine would dare “kill the flea,” so to speak, at least not in public view.

Like vampires and vampire bats, the flea feeds on human blood, but in the sixteenth century it sucked with much more meaning. Aristotelian science, popular in the Renaissance, imagined coitus as the mingling of the man and woman’s blood—just the perfect thing to fire the imagination of one of the period’s most clever poets, John Donne. In the opening to his sonnet “The Flea” (1633), the speaker tries to persuade his mistress to go to bed with him, using a flea bite as his come-on for coupling: “Mark but this flea, and mark in this, / How little that which thou deniest me is; / It sucked me first, and now sucks thee, / And in this flea our two bloods mingled be.”

The mistress remains silent throughout the poem. We never hear her speak. Clearly, however, she has been stewing. For, in the last stanza, she destroys the speaker’s overblown argument by literally taking matters into her own hands. She kills the flea, which brazen act draws a shriek of protest from the speaker: “Cruel and sudden, hast thou since / Purpled thy nail in blood of innocence?” In her mind, the need for revenge; on her fingers, the evidence of the abuse of puce.

Donne describes a woman who breaks convention to assert herself: I’ll kill the flea myself, she seems to be saying, and remain whole and intact, to boot. Her undersized revolutionary act did not go unnoticed. Just a few years later, for example, the Renaissance French painter Georges de La Tour made that same bold statement the subject of his painting, La Femme à la puce (ca. 1640), sometimes translated as The Flea-Catcher. His famous Femme brings to a conclusion the history of puce.

A woman, draped loosely so as to reveal her breasts and a good deal of her mid-section, sits in front of a candle with a flea trapped between her thumbnails: we catch her in the act of killing. She makes visible the desire of the woman in Donne’s poem, to put an end for all time to such demeaning, flea-sized sexual foppery. Indeed, one needs a magnifying glass to see the flea in La Tour’s painting, and even then it is doubtful one could actually make out its tiny shape. The flea seems to have totally disappeared. We are aware of it solely in La Tour’s title. Woman has triumphed, and that is in part why some art historians choose to identify La Tour’s lady as Mary Magdalene—more upstart and aggressive than most women in the Bible, more so than her discreet sister, and more so, certainly, than that other Mary.

And thus all we can really see, and what has been left behind in the painting, is pure color. La Tour has bathed the entire canvas in a purple brown or brownish purple, depending on how the candle illuminates parts of the background. The Flea-Catcher, a radical painting in the history of art, takes on a bit of philosophical importance, as well. For La Tour destroys not just the animal, but also the sexual origins of that single, sneaky, most playful and dangerous color, already a part of the French palette by La Tour’s time, la couleur puce. The flea is dead—“out of the picture.” Only the pure color remains, cleverly present in the painting’s title, this time in the second meaning of puce. And that’s the color we use today—still elusive, still playful, but decidedly asexual.

Even after some three hundred years, ask what color puce is and most people will immediately think of puke—a yucky green or even a slightly ratty brown. They have no idea of purple brown or brownish purple, and know nothing at all of fleas or flirting or bloody murder.

Barry Sanders spends his time writing in Pasadena and Portland. His last book, with Francis Adams, was Alienable Rights: The Exclusion of African Americans in a White Man’s Land, 1619–2000 (Harper Collins, 2003). Two books are forthcoming: The Green Zone: Militarism and the Degradation of the Environment (AK Press) and Unsuspecting Souls: The Disappearance of Human Essence in the Nineteenth Century (Counterpoint Press).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.