Head Trips

The social inversions of the comic foreground

Jordan Bear and Albert Narath

For more than a century, any promenade down a seaside boardwalk has required a stop at an apparently nameless apparatus: a painted wooden façade featuring a colorful character in an outlandish situation with a hole where its head should be. A tourist playfully inserting his or her head into the cartoonish scene is then recorded for posterity by a professional photographer. The genre has its favored iterations, from the weightlifting hulk to the bathing beauty, the swimmer perilously clenched in the mouth of a shark to the novice aviator nervously clutching the controls of an airplane. As one of the omnipresent features of visual mass culture in American life since the end of the nineteenth century, these façades offer the possibility of radical transformation in the guise of carefree recreation, a chance for the working-class beachgoer to become, safely and fleetingly, someone very different. As with any element of quotidian experience that seems always to have existed, the photo-caricature or comic foreground (two names given to the innovation by its inventor) does in fact have a genealogy—a complex one that winds its way through the rise of modern culture.

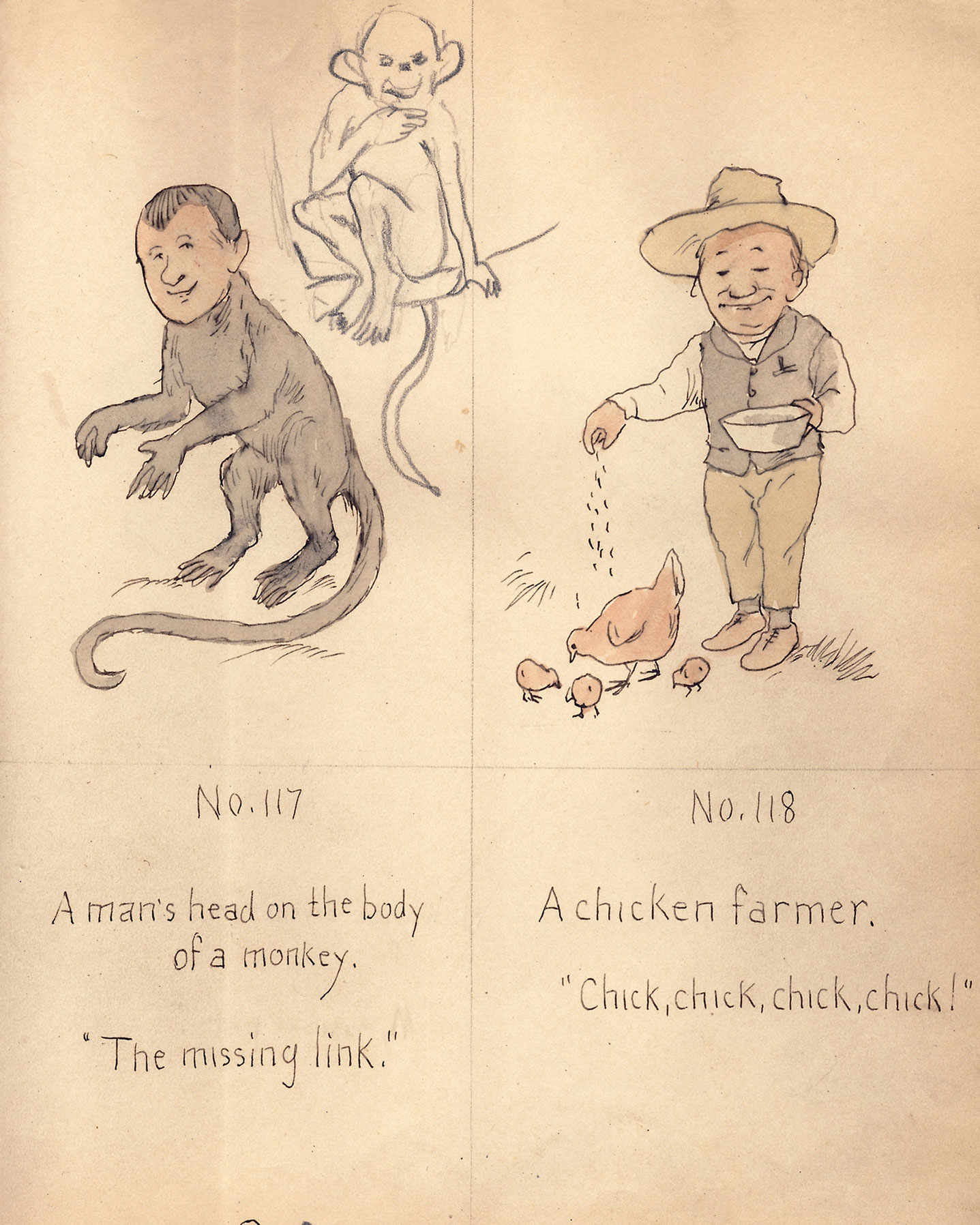

Comic foregrounds were but one of a series of contributions to mass culture by the polymathic Cassius Marcellus Coolidge (1844–1934), who also gave the world the now-canonical “dogs playing poker” paintings and a comic operetta about a mosquito invasion in New Jersey. By the time Coolidge applied for a patent on comic foregrounds in 1874, his fertile imagination had begun to generate an astonishing array of scenarios for his invention. Buried for many years in the basement of cultural obscurity, along with the reputation of their author, Coolidge’s recently rediscovered sketchbooks are alternately whimsical and morbid, serving as a laboratory for his ambitious plan to be the exclusive fabricator and distributor of comic foregrounds to the burgeoning class of low-end photographers who competed with sideshow barkers for the beachgoer’s spare coins. In this trove of over two hundred drawings, we see a few discernible patterns in the transformations that he imagined the leisurely stroller might be enticed to undergo.

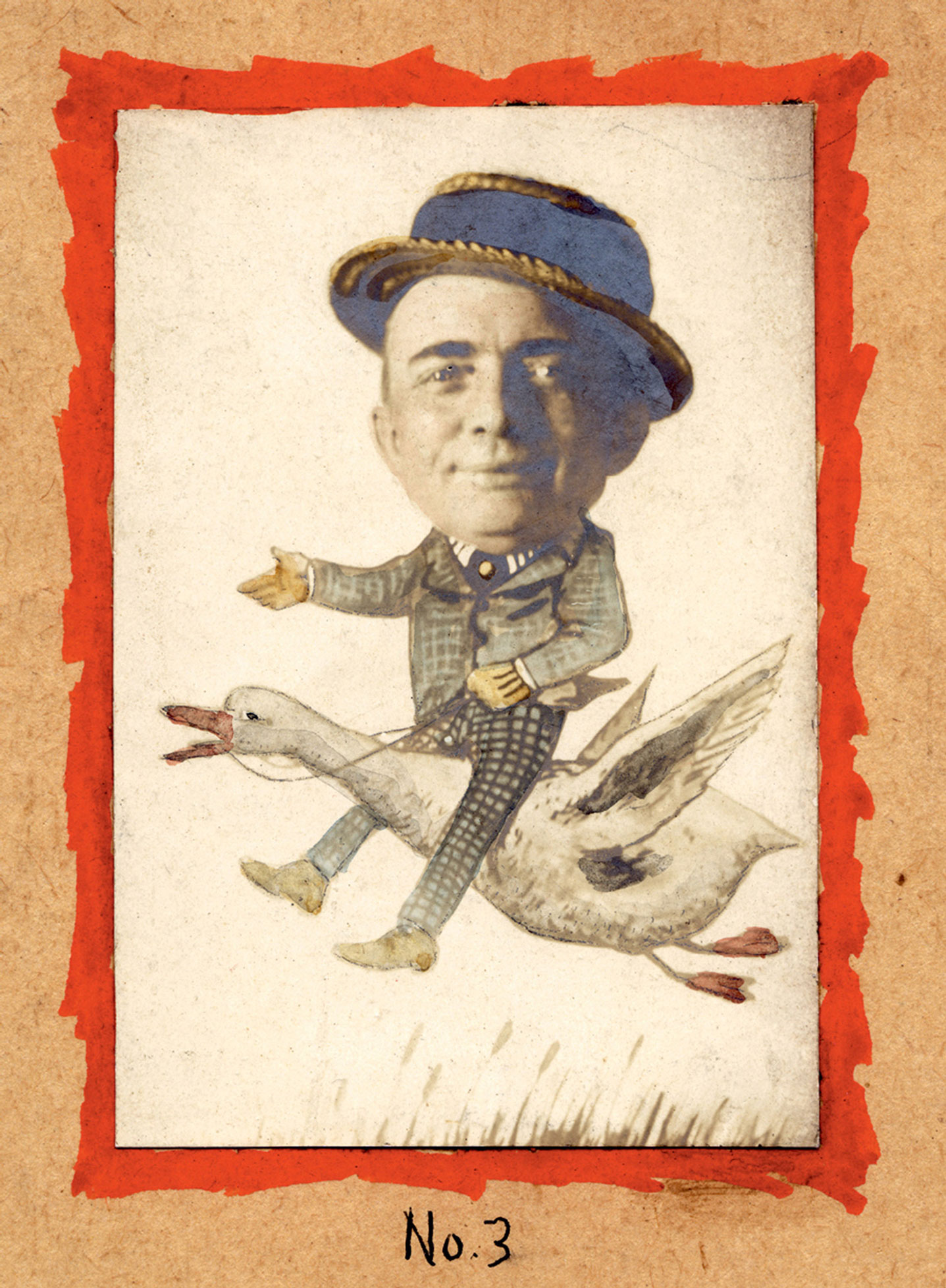

The animal kingdom proved to be a popular source of inspiration. In one sketch, a man’s head is drawn on the body of a monkey accompanied by the wry caption “The missing link,” while in another, a photograph of a head (Coolidge’s own) in a boater hat is collaged onto a drawing of a man riding a goose above a sketchily rendered marsh. Playing with scale was also a reliable source of humor. In one of Coolidge’s advertisements for his invention, a tiny body holding a glass of champagne in one hand and a bottle in the other is combined with an oversized photograph of a smiling visage, again Coolidge’s own. “A Happy New Year!” the text proclaims. “Now is the time to order Coolidge’s comic foregrounds for making holiday post cards!”

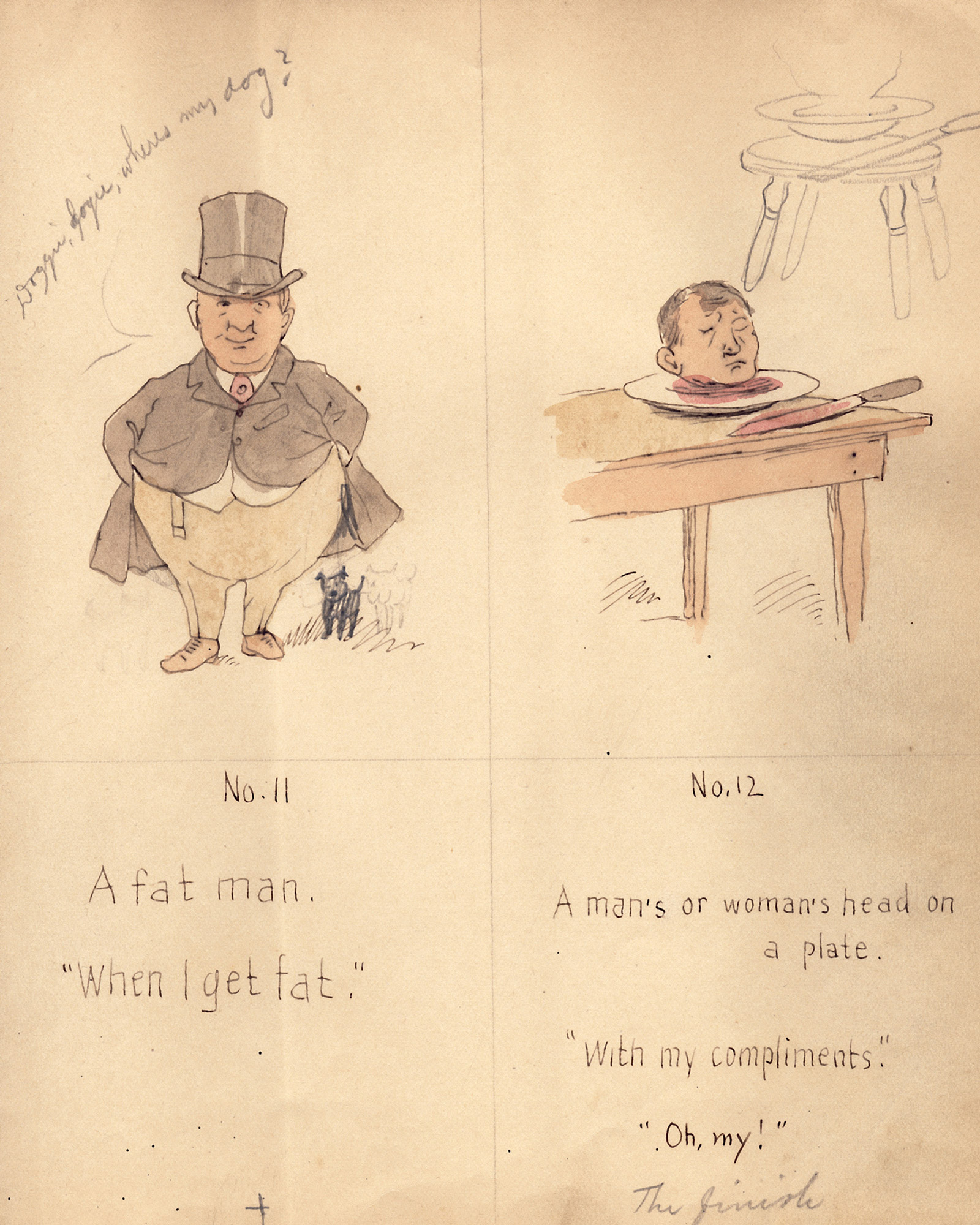

Coolidge would also fashion foregrounds that playfully thematized the very illusion on which they relied, namely a head disassociated from its real body. His sketches are populated with a cavalcade of severed heads, among the most memorable of which is one being served on a platter for the epicure’s consumption. The symbolic decapitation effected in the comic foreground playfully echoes the brutality of the stories of Medusa, Judith and Holofernes, David and Goliath, and John the Baptist, all of which had helped to insinuate the motif of the errant head into art history. Caravaggio, for instance, wielded his brush in execution of all four of these tales. But visual culture lost its head over decapitation at precisely the same moment as Louis XVI, when the House of Bourbon fell with a less-than-regal thud. From 1793 on, beheading signified violent revolution, transformation radical enough to bring a monarch to his knees and elevate a diminutive Corsican to the rank of Emperor. That year, the acerbic satirist James Gillray, observing the scene from across the Channel, produced a colorful print depicting an “exact Representation of that Instrument of French refinement in Assassination, the GUILLOTINE.” Here, the decapitated body of the king slumps on the wooden platform, his severed head issuing a stream of vaporizing blood on which Gillray’s royalist message is inscribed. The nature of Gillray’s oeuvre, which ranged from cheap trade cards to highly finished academic engravings, suggests the extraordinary mobility of this motif and its migration into increasingly popular visual media. An exercise in traditional caricature of a political milestone, the print nevertheless reaches a level of gleeful gore seldom seen in the work of Gillray’s contemporaries. The uniquely transgressive pose of the supine body separated from its head made a clear appeal to the popular taste that was beginning to supplant the academy as the arbiter of artistic fortunes.

The revolutionary possibilities embedded in the image of the wayward head migrated readily into Victorian instructive games, those rational amusements that sought to reconcile didacticism with the insatiable appetite for play harbored by the working and middle classes. One example is a game titled “The Clothes Make the Man,” consisting of cards illustrating what the explanatory text called “The Ranks and Dignities of British Society.” The cards features hand-drawn figures representing each of the ranks, from King, Duke, and Marquis to the lowly Scottish Highlander. A small hole cut into the figure’s face allows another card—depicting a beggar in his tattered rags, walking stick, and upturned hat poised to receive the charity of passersby—to be aligned behind it. Thus, the visage of the tramp melds seamlessly with the grand accoutrements of the aristocracy in a Dick Whittington-like rise from poverty to prestige.

One could interpret the political thrust of the game as implying that social rank is merely a matter of trappings, and that meteoric social mobility is a possibility in games, if not in life. However, it may be more precise to consider this artifact in relation to one of the few sanctioned spaces for ribald recreation in early modern Europe: that of Carnival, the pre-Lenten festival in which all standard hierarchies and ordering systems were temporarily transgressed or inverted as a safety valve for class tensions. The heritage of Carnival focuses our attention on the transience of the beggar’s identities. His mobility will not lead to a secure position among the landed gentry; in fact, like Carnival, which reduces social pressures only to allow for the continuation of the dominant order, the game works to reinforce the hierarchical rigidity that it temporarily overturns. This carnivalesque space is not too conceptually remote from the later space of mass culture, one in which lowbrow amusements, such as Coolidge’s, would also release class tensions through similar forms of temporary social inversion. Unlike the peasant at Carnival, however, Coolidge’s working man does not even achieve the title of King for a Day; King for a Few Seconds would have to suffice.

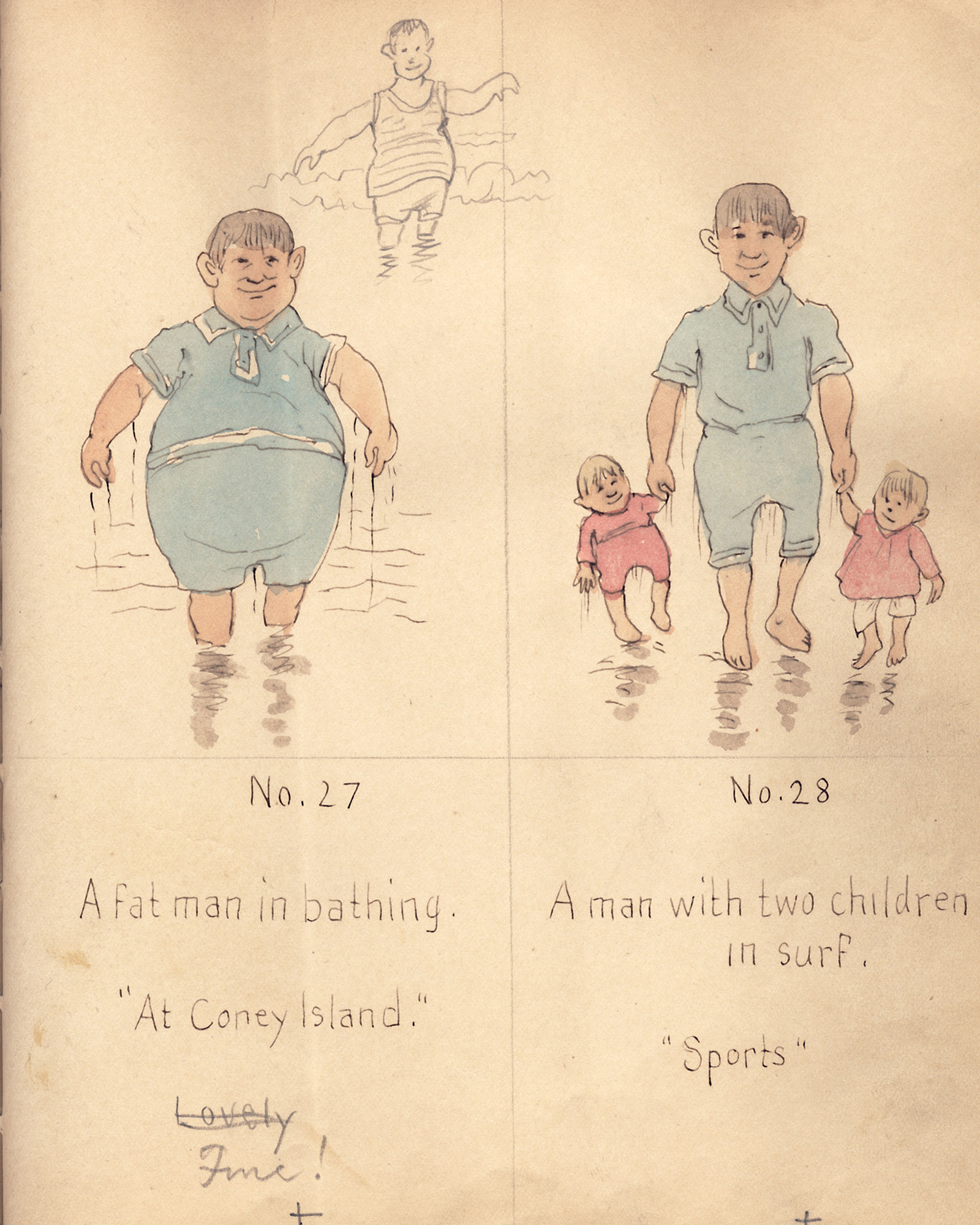

While the comic foreground was the culmination of a long trajectory of visual metamorphoses, it also registered the birth of a very different sensibility. For all of its emancipatory magic, it was the commonplace that was ultimately the countervailing realm of Coolidge’s invention. For what escapist liberty was achieved by a scene of wading in the tide, precisely the recreation that the boardwalk photographer’s patrons could engage in just a few feet away? What urge was satisfied by paying to see oneself represented in a simulacrum of a quotidian, readily available experience? In many of Coolidge’s sketches, the scenes depicted are simply vignettes of everyday modern life: driving in an automobile, dancing with a partner, or stepping up to home plate to swing for the fences. The success of Coolidge’s contrivance, then, was not exclusively—or even predominantly—based on the imaginative setting into which the customer might be inserted. Rather, it was the possibility of memorializing the act of being represented itself—of recording one’s own re-creation as an image—that seems to have captured the imagination of the photographer’s clients. The desire for a souvenir photograph of oneself participating in this facsimile version of experience is an eloquent articulation of the conundrum of hyperreality. This logic, and the particular innovation of mass visual culture that helped to express it, gives us a telling glimpse into the contours of our own experience, in which the copy precedes the original, and the meaning of transformation becomes ever more indistinct.

Jordan Bear is American Council of Learned Societies / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow in the Department of Art History at Columbia University. He has worked in the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he writes regularly about photography for publications including the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and History of Photography.

Albert Narath, currently based in Berlin, is a doctoral candidate in modern architecture at Columbia University and a Paul Mellon pre-doctoral fellow with the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art. His writings include “Modernism in Mud” (Journal of Architecture, 2008) and he is completing a dissertation on the neo-Baroque in Germany.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.