In the Orchards of Nostalgia

Hiding in plain sight

George Makari

Before I stumbled onto Eus, my only trip to France was an empty cliché. Backpacks on, my longhaired college pals and I celebrated our arrival by drunkenly tossing a Frisbee in the gardens of Versailles. We burned our way through cultural landmarks and topless beaches, and in the end, met no one who was French and no one who was topless.

A few years later in New York, I fell in love with an American woman who had spent her childhood in France, and in 1987, I accompanied her home to a medieval village perched in the Pyrenees. The place itself was a cluster of houses, a zigzag of cubes and rectangles made of white rock and orange terracotta roofs. Wide at the base, the village lifted and narrowed as it moved up the mountainside, peaking in an eighteenth-century Baroque church with a bell tower. Down in the valley, there were verdant orchards and beyond that a range of gray mountains that rolled out into an immense vista and somewhere became Spain.

After following a perilous little road that snaked its way higher and higher, I first arrived at the village. Amid faint outlines of formerly terraced land, hand-painted markers pointed hikers higher up the mountain to a ghost town called Comes. In 1930, the final inhabitants of Comes dug up their dead and carried these remains and their few possessions down into the valley. At that time, Eus seemed headed for a similar fate, but the next decade brought a wave of settlers that saved it from ruin. By the time I set eyes on it, the village was thriving; along its maze of footpaths, there was carefully tended thyme and Barbary cactus, red and yellow roses, Pyrenean irises, fig trees, hanging muscat grapes, and aloe.

Still, for a child of the New Jersey suburbs, it was as if I had fallen backward in time. There were few phones or televisions, and no supermarkets. People slipped notes under doors to pass on invitations or news; on Tuesday, everyone carried their baskets into town for the fair. Everything looked ancient, from the stone houses and the skinny cobblestone passageways to the tin Deux Chevaux cars. Washerwomen could be found at the village well, and builders used cow dung for cement. In the morning, the bell in the church tower rang on the quarter hour. It also called people to prayer in the morning and evening for “l’Angelus,” and when a villager died, it tolled through the day.

The inhabitants also came from another time. Take our neighbors.

Georges Grigoroff had been a warm, jolly uncle to my wife in her jeunesse. He was short and stocky, and his white hair sprouted wildly from under his beret. Bushy eyebrows framed his electric blue eyes. From afar, he resembled any number of French villagers; dressed in blue and black, skin craggy from the sun, severe, arms clasped behind his back as he walked.

Though he cultivated grapes for wine and bees for honey, Grigoroff was an intellectual. The word may sound pretentious, but after being popularized during the Dreyfus Affair, the term caught on in France. In Grigoroff’s case, this meant that by day he was an expert on agriculture and land reform, and at night a political militant, an anti-authoritarian syndico-anarchist. There were others like him in Eus—elderly men and women who had hauled their convictions over these mountains and repopulated this village after their cause was lost in Spain.

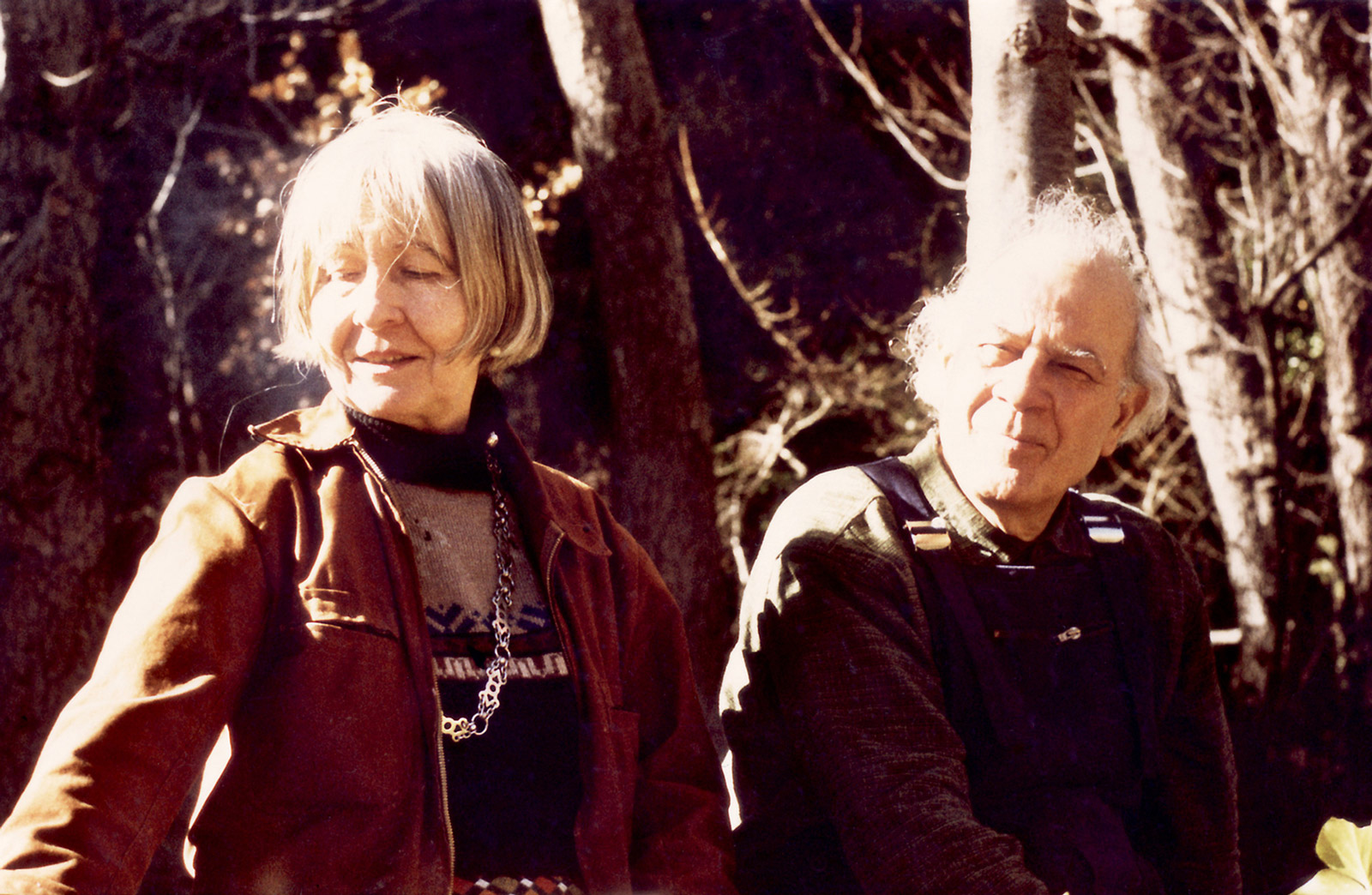

Grigoroff’s companion of forty years, Madeleine Lamberet, lived in an adjoining house. An ebullient painter well into her eighties when I first met her, her porcelain skin was accentuated by a shock of beautiful white hair, impeccably coiffed in page-boy style. A student of the painter Maurice Utrillo, she had become a committed anarchist around 1936. She was passionate about Romanesque art, flamenco dancing, and fight-the-power demonstrations. Attracting a coterie of artsy friends fifty years her junior, Madeleine seemed like an ageless Pan. Filled with an aesthete’s joys, she perpetually pronounced things beau and charmant in a mellifluous voice.

Georges and Madeleine would darken, however, when recounting the Spanish Civil War. They spoke incessantly of Buenaventura Durruti, Franco, and the collapse of Barcelona, as if on a brief vacation from 1939. They never missed the July 19th reunion of Spanish loyalists. In one of her last letters to us, some sixty years after the fact, Madeleine could not help but note that the 19th was approaching, writing plaintively of “this revolution that holds all our heart.” It was their great defining tragedy, and, with them, it lived on. Meeting Georges and Madeleine was like stumbling upon soldiers who had gone into hiding up in the hills and refused to believe the war was over.

During the 1970s, this couple became heroes to the youth of Eus who tagged along after them, memorized their protest songs, listened with rapture to their tales, and imagined Eus to be a classless commune. To have fought fascism, to have risked everything by going underground into the resistance: these two had come through the fire that had forged the next generation’s world. Utopian believers in freedom, in collectives founded only on individual desire, Georges and Madeleine exemplified these credos with their disdain for all centralized authority and institutions like marriage. Though inseparable and doting, they maintained their independence by residing in attached houses. Cool.

Though he could be hilarious, witty, and wry, over the years, I must admit, I grew weary of Grigoroff. He had become harder in old age, and with me, he simply could not contain his disdain for Americans. I remember sitting at his dining table, and as always, our conversation turned to American Imperialism, the situation with the blacks in the United States, and whether I had read John Steinbeck (not again!). Did I know about these things? It was as if we were playing chess and with these few moves, he had checkmated me. He enjoyed pinning me to the losing proposition of being his America, while he waltzed away as the enlightened egalitarian. Even though I had read Steinbeck and had not voted for Monsieur Reagan, I knew that didn’t matter. If I wanted him to be my French intellectual, I would have to bear up as his pigheaded American.

Still, our arrangement confused me. As an anarchist, Grigoroff reserved his most intense hatred for the Soviets, the same enemies as Monsieur Reagan. He insisted that Stalinists had murdered Durruti and betrayed the cause in Barcelona; they had turned the dreams of liberty and equality into a nightmare. Grigoroff’s refusal to forget burned like a long dark fuse in his eyes. I once heard that he had staged raids inside Spain, like the famed guerrilla Sabaté who had hidden out in Comes and Eus for a while after the war, but I did not know how heavy his hatred was until he invited us to his tiny atelier in Montmartre. It was a closet-sized garret stuffed from floor to ceiling with anti-Communist pamphlets, declarations, and manifestos, all written and in some cases printed by Grigoroff himself. As I entered, the piles trembled and threatened to fall. Looking around, I spotted a cot and a hot plate. It was not so much a livable space as a secret room for his rage. Armed with a pen and a host of pseudonyms, such as Georges Balkanski, Georgi Hadjev, and George Khadjev, he wrote tract after tract, seeking to topple a superpower. It seemed fanatical and breathtakingly romantic, certainly from another century. He lived as if we were still in a world that could be transformed by freethinking pamphleteers holed up in Paris.

And then, an extraordinary thing happened. Grigoroff’s dream met and mixed with a million others’. This man who had refused to let go, chanting, singing, in his own way praying, was miraculously given his due. In 1989, the Soviet empire and its Iron Curtain disintegrated. Georges Grigoroff won. And at that moment I discovered that our next-door neighbor was not French at all.

• • •

According to many in our village, Eus is neither French nor Spanish but Catalan. That is the most recent answer to the troubling questions of identity that have roiled this border region and given it many names: Occitania, Catalunya Nord, Languedoc, Rousillon, Pyrenees-Orientales. Recently, a bureaucrat incurred great ridicule by proposing that the region be renamed Septimanie, in honor of its supposed Visigothic origins.

This vast wall of stone, the Pyrenees, has always constituted a natural border—but between whom and whom? The reply to this question has changed, often at the point of a sword. The reminders are everywhere. Throughout the mountains, impossibly perched fortifications mark the landscape. On sheer cliffs, the Cathars built their castles. Manicheans, these heretics proclaimed the material world to be made by an evil God, and they made this region their own, until they were slaughtered by the papal decree of a man named Innocent. Long dependent on the largesse of the Count of Barcelona, the region fell to the French in 1462, and was taken back by the Spanish thirty years later, only to be ceded again to the French in 1659.

Solidly French since then, the inhabitants of the Pyrenees still seemed to hedge their bets. Hard to win, harder to control, these unconquerable mountains remained home to refugees, criminals, eccentrics, loners, searchers, utopians, and runaways. Here, a man might forget his past and disappear. Here, believers could build their new worlds. A Protestant or Jew might worship in peace; a Spaniard might pass as French; a fugitive might lose the law. The place became associated with cunning and the art of the double-cross. The French spoke of their southern compatriots as untrustworthy and shifty; the Spanish warned of a northern region filled with heretics and outlaws.

But such a place had its uses. Over the last, cruel century, many in Europe were forced to disappear, and so they came. Les évadés, the locals called them. In 1939, the defeat of the Spanish Republicans brought the first torrent of refugees over the mountains. The cellist Pablo Casals found shelter in the valley below Eus; the poet Antonio Machado dragged himself to the port town of Collioure only to die. In a region with 223,000 French, some 250,000 exiles poured in. Later, when Franco outlawed the use of the Catalan language, another exodus began. For those who knew no other language, talking itself had become a crime.

Grigoroff was one of those exiles who adopted France as his refuge. But when the Soviet Union fell, he announced that he would now leave forever and return to Bulgaria. It was no secret that he had been born in Sofia, but people were shocked. Wasn’t Georges one of those who had given up his birthplace for the idea of being French, for the ideals of liberté, fraternité, and égalité? If anyone seemed to have liberated himself from the sentimental claims of a birthplace to follow freely chosen political commitments, it was him.

Then there was the matter of his other wife. Villagers were stunned to learn that when Georges departed Bulgaria nearly half a century earlier, he had been forced to leave behind a woman he loved. Some had known and forgotten; others, like myself, had never known. If she was not really a secret, neither was she ever discussed. When I found out about her, it suddenly became clear that Georges’s arrangement with Madeleine was predicated not only on the spirit of anarchism but also the ancient proscription against polygamy.

Afterwards, many of us tried to piece together clues we had chosen to overlook. Once, Grigoroff announced to the daughter of a local anarchist and veteran of the Spanish Civil War that he wanted to hold a banquet and reveal all the secrets he’d been hiding. A banquet was held; he said nothing. There were other moments, too, but to the exiles from Spain, there was nothing more to know. Georges was a brother from their strangled cause. He stood before them in that light; he was that.

And yet, he had another past. After the fall of Spain, he fled over these mountains but continued to Sofia where he reunited with his family, married, became an anarchist leader, and then, during World War Two, was placed in a concentration camp. Liberated in 1944, he had a short taste of freedom before the Soviets marched into Bulgaria and swept him into one of their political prisons. Of the tortures he endured, he told one to my wife, then twelve, perhaps because it had the air of a schoolyard game gone mad. Soldiers drew a chalk circle on the floor of his cell and a cross on a facing wall. While playing cards, they instructed Georges to stand inside the lines and stare at the cross. For days. He was not to move. He was not to stop. When he collapsed, they whipped him, doused him with water, and propped him back up inside the circle.

As for Madeleine, she too fled over these mountains and did not stop, but went on to Paris, which soon fell under Nazi occupation. As a known anarchist, her life was in danger. She made her way into the underground, where, with her sister Renée, she organized the clandestine French Anarchist Federation. Using her skills as a painter, she forged passports for Jews and smuggled these papers to a contact at Gestapo headquarters in Paris. (When my wife and I asked if she was frightened, she looked at us sweetly, as if we were strange children.) After the war, when the time came to liberate a comrade in a Soviet prison, a man she knew from her days in Barcelona, this fearless woman took the assignment. Posing as an enthusiastic Marxist painter, she beguiled the Bulgarian cultural czars and somehow helped free the man. It was Grigoroff. I know it sounds implausible, too James Bond to be real, and perhaps it is not true. But I wonder if during those horrific years the only tales that did not end in death or silence were the implausible ones.

They lived together as lovers in Paris, and arrived in the village around 1968. The couple bought two ancient stone ruins side by side and restored them. From their terraces, they could peer out each morning at the mountains they had once scaled in flight. All around them were reminders of their brief victory and exodus: the Catalan language, the shepherds’ paths through mountain passes that had carried them to safety, the dried ham that had sustained them, and the Mediterranean sun. They pointed themselves back in time, back to the beginning that allowed their worlds to entwine. They held Barcelona tight, refusing to let go, watching documentaries, reading histories, and surrounding themselves with the days of hope, the broken promises, and the massacres.

Soon, myths grew up around them, myths they did nothing to dispel. Those of us who had disappeared into these hills for our own reasons filled our imaginations. Georges became “l’Anarchist”; Madeleine, his Simone de Beauvoir. But the collapse of the Soviet Union altered the geography of their remembrances; it awakened them from a long nightmare that had nonetheless given them each other, and it forced a choice upon them.When the walls of Europe collapsed, Georges was free to take back a life that had been torn from him. All he had to do was step over the last forty years. Or he could refuse that for this life here, for her.

He left.

In Eus, the villagers were appalled. To this day, no one can quite forgive him for abandoning Madeleine, and in so doing, breaking the spell those two cast over the village. Even though it would be unfair to say he tried to deceive us, many felt it was true, so strong was the power of their fantasies. And though Georges and Madeleine died over a decade ago, each year when we return to the village, we discover people still can’t stop talking about them. No one can get over it.

It was said, however, that douce Madeleine accepted Georges’s decision. Gossips whispered that she herself had wearied of the circle within which history had trapped them. In 1997, this timeless woman was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and eighteen months later, on 9 May 1999, she died alone in her apartment in Paris. As for Grigoroff, his return to Sofia was the cause for some celebration. His tireless attacks on the Communists were lauded by none other than the King of Bulgaria, an honor not without irony for an anarchist. However, on 12 October 1996, he too died alone. After a brief reunion, his Bulgarian wife had divorced him, saying he was no longer the man that she once knew.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.