Acomocliticism

Aesthetics along the bikini line

Blake Gopnik

Aesthetic ideals, imagined as remote and superlunary, may never be more than lowly preferences putting on airs. If only he had grasped that possibility, John Ruskin could have had a thrilling wedding night. Instead of being defeated by the sight of his bride’s unideal pubic hair (that is one longstanding parsing of the “certain circumstances in her person” that he later said had deflated him), Ruskin could have followed many other aesthetes and artists, and simply told her he preferred her shaved.

The smooth pudenda of Western art may reflect a grounded taste for hairlessness as often as they mark aesthetic elevation. Ancient Greece, source of our later Platonisms, was an acomoclitic place. The Greeks shaved and plucked and even torched. (Although there is still scholarly debate about the precise glabrosity achieved, and its Freudian implications.)[1] Some of their later followers, rather than standing heir to a philosophical tradition, were likewise victims of a capillary fashion. “Ideal” figures such as those in Antonio Canova’s hairless Three Graces might have gone Brazilian for “the convenience of pleasure, out of libertine curiosity and following the custom of the courtesans who modeled in Athens and Rome,” as Diderot explains when he discusses hairless statuary in his 1765 Salon.[2] Several decades earlier, John Dryden, translating Persius’s first-century Fourth Satire, annotates its reference to pubic depilation by citing “that effeminate Custom now used in Italy, and especially by Harlots, of smoothing their Bellies, and taking off the Hairs which grow about their Secrets. In Nero’s times they were pull’d off with Pincers; but now they use a Paste, which applied to those Parts, when it is remov’d, carries away with it those Excrescencies.”[3] (As late as the 1950s, Dryden’s note was still being expurged from editions of his writings.) Even art history’s most famously hirsute pudendum, seen in Courbet’s Origin of the World, is less natural than it seems at first glance. Under close examination by the chief of gynecology at a major American hospital, it revealed “evidence of waxing at the bikini line.”

Marcel Duchamp, though always conceived of as caring more about ideas than matter, “had an almost pathological hatred for hair,” according to his first wife, and is known to have requested pubic depilation of his lovers, to match his own.[4] His art reflects his taste: the spread-legged female nude in his Étant donnés, the magnum opus of his later life, is perfectly hairless. It seems that Duchamp’s smooth crotch has more to do with Burma Shave than with ancient artistic ideals and their ravishment by modern art.[5] Or rather, Duchamp may have caught on to Praxiteles and Canova as his precedents in lather.

As so often in art history, the Renaissance provides the test case for our argument. It is said that classical ideals were reborn among Renaissance artists, but it might be better to say that those artists caught on to classical tastes. In a letter published in the 1560s, the Venetian satirist Andrea Calmo wrote of a dream in which antiquity’s greatest heroines, from Helen to Dido to Lucretia, gave him a depilatory powder to bestow upon his lady.[6] Granted, those heroines don’t specify the powder’s place of application. Upper lips, too, were kept smooth in the Renaissance.

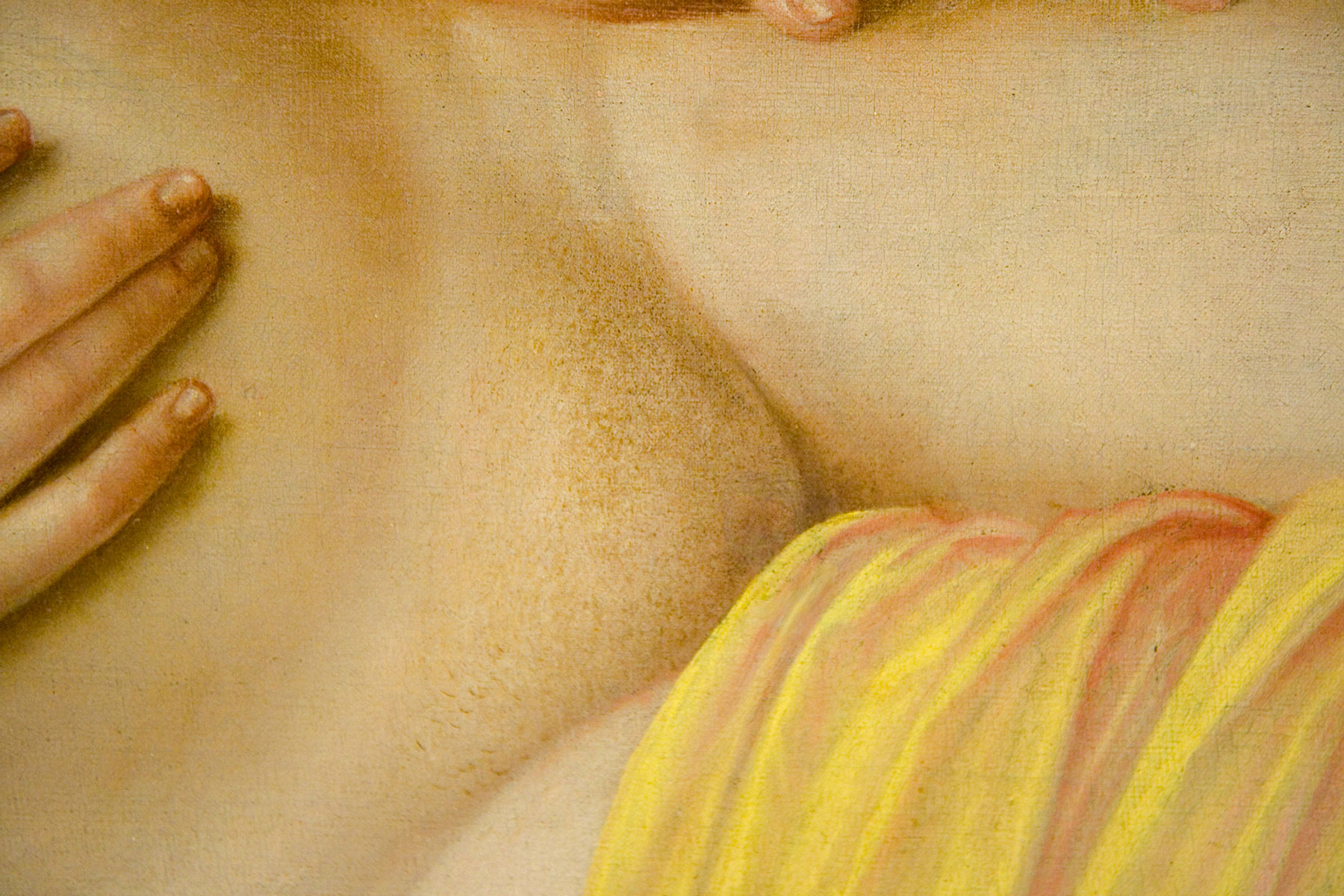

Depilatory geography is less approximate in a shamefully neglected print from around 1540 by the German artist Peter Flötner, in which a naked woman, perhaps personifying vanitas or nuda veritas, trims her mons veneris with a huge pair of shears.[7] And in 1544, once again in Germany, Georg Pencz, a follower of Dürer, provides additional evidence that ought to close our case for pubic realism. Pencz’s lovely painting of a sleeping nude, propped on one of the finest pillows in art, is now in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. The standard take on a picture such as this would describe it as a marriage of Italian idealism and a northern commitment to the real. The ideal seems to be there in Pencz, in a hairless pudendum worthy of the Medici Venus. But his realism reveals it, once again, to be nothing more than a preferred and available option. When observed very closely—rudely closely—the model’s lower belly reveals tiny flickers of black paint spaced across the pink of her skin.

Stubble.

- See Martin Kilmer, “Genital Phobia and Depilation,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 102 (1982), pp. 104–112.

- “… la commodité du plaisir, la curiosité libertine, et l’usage des courtisannes qui servoient de modèles dans Athènes et dans Rome.” Denis Diderot, Salon de 1765, in Salons, ed. Jean Seznec and Jean Adhémar, 4 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960), vol. 2, p. 210.

- Quoted in Maurice Johnson, “Dryden’s Note on Depilation,” Notes and Queries, no. 196 (27 October 1951), p. 472.

- Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor, Un échec matrimonial: le coeur de la mariée mis à nu par son célibataire meme (Dijon: Presses du réel, 2004), p. 69.

- See Michael R. Taylor, Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2009), p. 69.

- The gift is “una polvere da butar via e far cazer quanti peli vu havé adosso.” Andrea Calmo, Le lettere di Messer Andrea Calmo, riprodotte sulle stampe migliori, ed. Vittorio Rossi (Turin: Ermanno Loescher, 1888), letter 24 of book 4, p. 307. See also Lynne Lawner, The Lives of the Courtesans (New York: Rizzoli International, 1987), p. 28.

- Reproduced on p. 58 of Ann Sophie Lehmann, “Op de grens: Lichaamshaar in de kunst van de Renaissance,” in De grenzen van het lichaam Innerlijk en uiterlijk in de Renaissance, ed. Arie-Jan Gelderblom and Harald Hendrix (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1999), pp. 47–73. This is the main text on pubic hair in Renaissance art. A better image of Flötner’s print is available online in the British Museum’s collections database.

Blake Gopnik is the chief art critic of the Washington Post. He is currently conducting research on eccentric perspective in Dutch art. His work can be seen at www.blakegopnik.com.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.