Barbers and Barbarians

Episodes in the history of Argentine hair

Jorian Polis Schutz

In Argentina, you see boys wearing their hair long and wild. For this, shampoo must be foregone for weeks and haircuts for months so that maximum unctuousness may be achieved. The savage impulse must withstand the perennial opposition of forces for shortness—for there is always a national mythology of hair to grow out of and into. The goal is to achieve a look that embodies a descriptor that a century ago would have conveyed deep derision, but which today in Argentina means “awesome” or “perfect”: bárbaro.

Argentina is one of the places in the world where the hairdo of European “civilization” has most earnestly (and anxiously) been worn. This is a country that spent more than a century looking back over its shoulder, longing to restore the umbilical connection to a Europe that largely peopled its shores, while horrified to face its own uncivilized interior—the vast Pampan expanse. Hair became one site for this national psychodrama between civilization and barbarism.

Facundo is a type of primitive barbarism. He recognized no form of subjection. His rage was that of a wild beast. The locks of his crisp black hair, which fell in meshes over his brow and eyes, resembled the snakes of Medusa’s head.[1]

Facundo, portrayed by Sarmiento as illiterate, would perhaps have been gratified by such a grand mythico-literary treatment. But whatever he actually was, this “tiger of the plains” became the original gaucho malo, or outlaw, a libidinous giant on the frontiers of the nation, his face “sunk in a forest of hair.”[2]

Sarmiento later became president of Argentina, ushering in an age of modernization, immigration, and manifest-destiny-style military advance that ultimately made the frontier and all of its fast-disappearing barbaric inhabitants into phantasmal objects of national nostalgia. This he did in part by invoking on his mythical spectrum the opposite of the animalized interior of his own nation. Already, in his influential book of travel essays, published as Viajes (1851), Sarmiento had praised above all the jewel in the crown of the dynamic North American scene—the “Brahmanic race of the United States,” the inhabitants of New England. These Northerners disciplined their new populations, inculcating them with their own ethic in schools, in books, in elections, and in all their other institutions. From this dissemination of the spirit of enterprise came the great achievements of civilization and colonization—the railroads, banks, societies, and so on.

Sarmiento called New England his “fatherland of thought” and proposed to establish a corresponding elite in Buenos Aires. Fueled by European immigration and progressive education, this cadre of what we might call “barbers of barbarianism” was to be charged with the responsibility of replacing the cattle ranch with the factory, the wild horseman with the disciplined rower, and all communication inefficiencies with the lightning-quick telegraph. A new nation, to be called the United States of the Río de la Plata, was to be forged from a united Argentina and Uruguay. “Our Pampa makes us indolent,” Sarmiento proclaimed, “and the easy feeding of our shepherds keeps us stuck in incompetence.”[3]Sarmiento declared war on the zeitgeist of his nation, and it was hard not to listen to him—even long after his death. “Sarmiento the dreamer continues dreaming us,” wrote Jorge Luis Borges in poetic tribute.

Hernández’s anti-Sarmientanism dates back at least to his first published work from 1863, Vida del Chacho (The Life of Chacho), a vitriolic polemico-hagiography that directly inverted the Facundo scheme by converting one of the caudillo’s allies into a true man of the people and Sarmiento into a cold-hearted assassin, indeed a bárbaro himself, a sort of South American Sweeney Todd:

General Peñaloza has been beheaded. The man ennobled for his unquenchable patriotism, his strength for the sanctity of his cause, the Argentine Viriathus, in front of whose prestige the conquering forces were smashed, has just been riddled with stab-wounds on his own bed, his throat slit and his head presented as proof of an assassin’s job well done, to the barbarian Sarmiento.[4]Hernández was sent into exile by Sarmiento in 1870, just as Sarmiento had been sent into exile by the dictator and cattle baron Juan Manuel de Rosas thirty years before. And, like Sarmiento with Facundo, exile gave Hernández the impetus to conceive on the mythical plane and the tranquility to conjure the Pampan figure that would become the most beloved in Argentine literature. Within the world of Martín Fierro, the forces for civilization and progress are revealed to be the very same that destroy the gaucho’s idyllic rooted life and turn him into a drunken killer. The expansion of the nation is shown to be a truer definition of barbarism, and the much-maligned long hair of the gaucho is valorized as a symbol countering the dehumanizing forces that press on him from above.

This was the age of the dawning of rock nacional, and messy heads were all over the scene. Government agents began breaking up concerts with tear-gas and detaining the rockeros that resisted. Albums with subversive content were censored or banned, and many artists were forced into exile. Rockeros met clandestinely in urban parks on weekends to exchange underground albums and publications. These were the years when thousands of people, mostly young, were disappearing without trial or trace. Wearing long hair was no joke, and no innocuous fact. It was an act of resistance that could only be made viable en masse.

This story has roots in two rather different “coiffure classics” from the previous dictatorship (1966–1973), when the state was first confronting homegrown rock music. In 1968, the RCA-backed band La Joven Guardía released “El Extraño con el Pelo Largo” (The Stranger with Long Hair):

Wandering through the streets,watching the people go by,

the stranger with long hair

goes, without worrying why

The song became one of the biggest hits of the nascent Argentine rock scene and was converted into a highly successful film of the same name, as well as a somewhat less successful follow-up album, which was co-promoted with Coca-Cola. Here was a great song with a Beatles-derived sound and a vague, acceptable kind of rock hair.

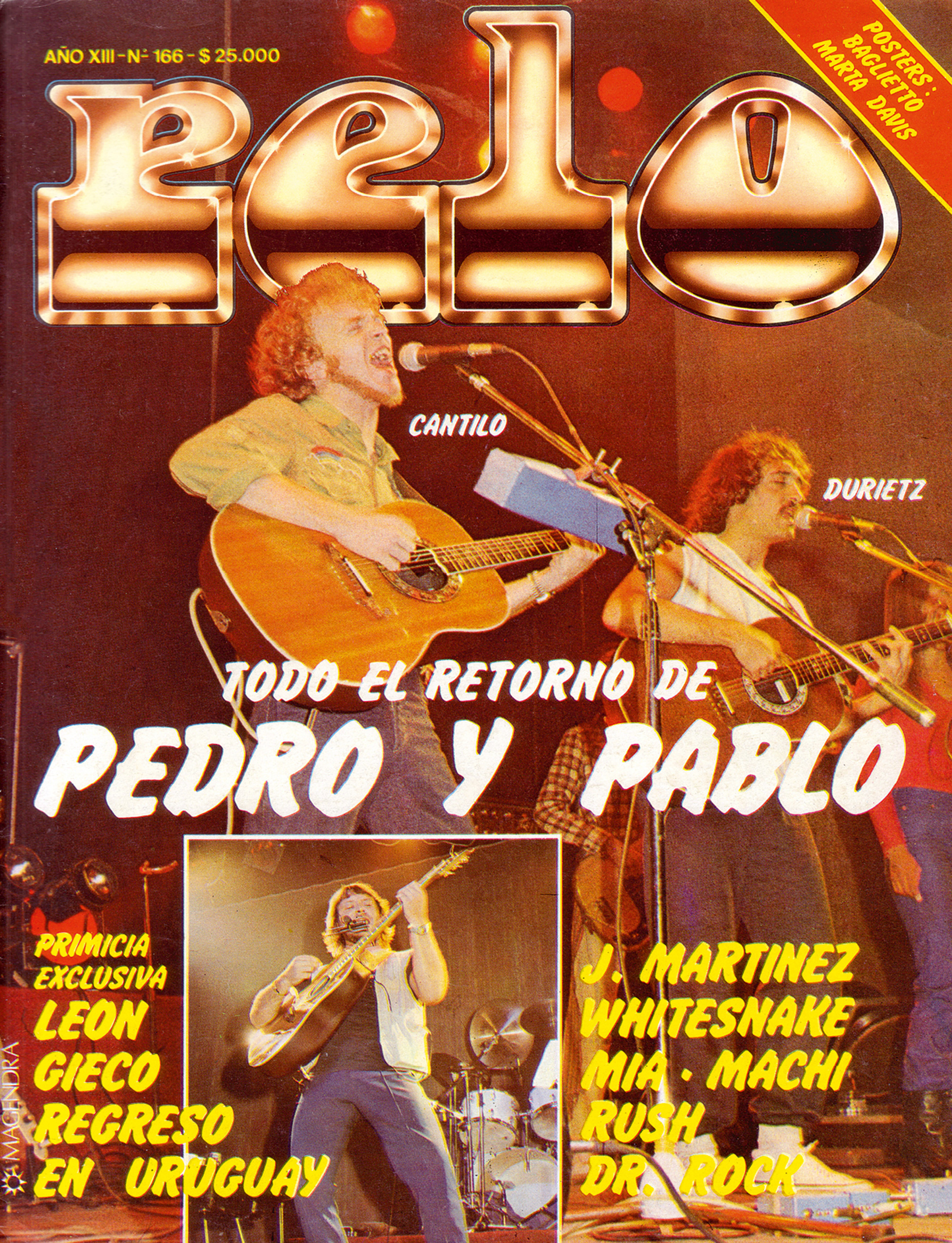

And then there was Pedro y Pablo’s social protest anthem, “Marcha de la Bronca” (March of Fury, 1970), which suffered a rather different fate:

Fury when they want meto cut my hair without reason;

it’s better to have free hair

than freedom with hair gel

The song came to be identified so closely with the passions of the young generation that its sequel, “La Leyenda del Retorno” (The Legend of the Return), was snuffed out by government censors and didn’t appear for another eight years. Later, under the far more severe Proceso dictatorship, Pedro y Pablo’s frontman Jorge Cantilo was forced into exile; when he was allowed to return in 1981—after General Videla had been replaced with the less hard-line Roberto Viola—it was only on the condition that he abandon the Pedro y Pablo name and never again sing “Marcha de la Bronca.” Here was a style that was more than a look, that brought heads together with pumping fists, and that retained its potency even a decade later.[5]

It was only with the rise of César Luis Menotti’s club Huracán in the early 1970s that an inspiring new style of Argentine play—and, indeed, footballer—was forged, and thus it was that on the eve of the 1978 World Cup, which Argentina was to host, the military regime found itself in the uncomfortable position of depending on a ragtag team of longhairs to deliver them a new sense of national pride. Menotti, a left-wing Peronist who himself wore shoulder-length hair, had been appointed to coach the national team by the administration of Isabel Perón in 1974. The team was traveling in Poland in 1976 when the military coup occurred, and upon its return Menotti offered his resignation. But the military junta needed this victory, and they dared not take the helm from Menotti—or the role of mascot from the mop-headed cartoon character Gauchito. Plus, in the wake of the heavy suppression of rock nacional, the authorities were glad to have Argentine youth focusing on a somewhat more controllable arena for passionate behavior and wild hair. The uncomfortable alliance resulted in a World Cup victory, one shared by long- and short-haired forces alike.[6]

It was the 1978 team that solidified the Argentine “look” on the world stage, with Kempes, Luque, Bertoni, Houseman, the goalie Filliol, and Menotti himself sporting variations on the wild look. Strange, then, that hidden in their midst was something of a budding renegade—Daniel “Kaiser” Passarella, their captain, who would return to coach the country’s team for the 1998 World Cup. Now shorn and serious, Passarella famously mandated that his players cut their hair to be part of the team. Apparently this provision led to a high-profile break with one of Argentina’s most popular players, Gabriel Batistuta (“Batigol”) who was consequently absent from the tournament. Interviewed later on television, Passarella responded to criticisms with a dose of professional rhetoric:

I answer with my work. I wake up early every morning. I go to work. This is my product, and I’ve come to work. … It’s not a military attitude, because it’s not that I like hair to be short. Not at all. But there are studies about this. They’ve done analyses of the players … the number of times they touch their hair when they have it long and when they have it short. I think it’s a discourtesy. Long hair is dangerous.[7]

- Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Facundo, or Civilization and Barbarism [1845] (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), trans. Mary Mann, p. 83.

- Ibid., p. 74. Translation modified. Mann renders the phrase as “half-buried in this mass of hair,” but Sarmiento’s original text uses the word bosque (forest). Facundo was nicknamed “the tiger of the plains.”

- Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Argirópolis [1850] (Buenos Aires: H. Consejo Deliberante, 1961), pp. 82, 84. My translation.

- José Hernández, Vida del Chacho [1863] (Buenos Aires: Del Dock, 2005), pp. 15–16. My translation.

- It seems especially fitting that all these socio-cultural convulsions were documented in Pelo (Hair), the leading music magazine of the era, founded in 1970.

- René Houseman would later remark on the team’s political ignorance: “I didn’t know what was going on in the country. Today I know, and it disgusts me. I gave my hand to Videla; today I’d prefer to cut it off.”

- Daniel Hadad, interview with Daniel Passarella, 2009, available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=8kWErRkIkZc. Accessed 2 December 2010.

Jorian Polis Schutz is a writer, publisher, and calligrapher living in Brooklyn, New York, and Boulder, Colorado. His publishing imprint, Orphiflamme Press, will release its first book, Varitan’s Illustrated Greek Myths, in spring 2011. See www.varitans.com for more on Varitan’s Illustrated Greek Myths.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.