The Freedom of Speech Itself

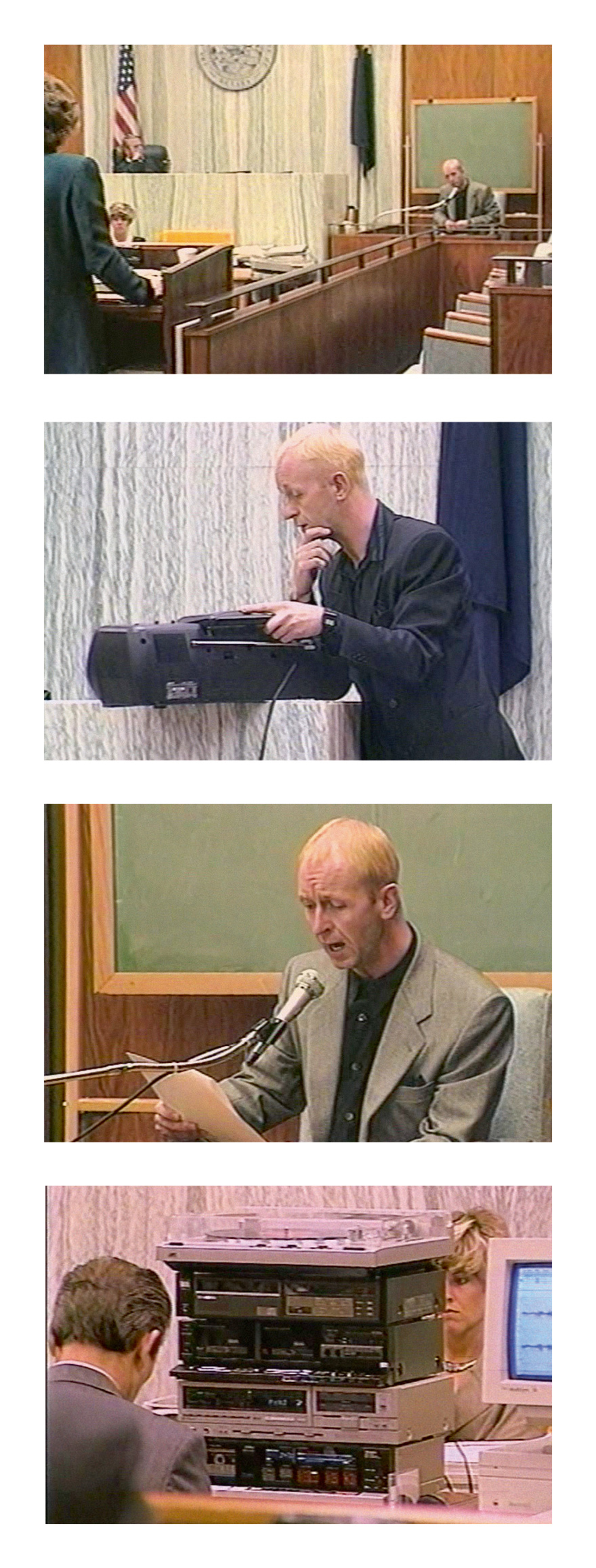

A contemporary chronology of forensic listening

Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Last week, a colleague and I spent three working days listening to one word from a police interview tape.

—Peter French, forensic audiologist and phonetician

Code E of PACE required police interview rooms to be equipped with audio recording machines, so that all interrogations could be recorded. This legislation was seen as a solution to claims that the police were falsifying confessions and altering statements made during interviews, as prior to this point all statements were simply written down “verbatim” by the police officers and then signed off on by the suspect.

Were it not for a handful of linguists practicing a rare strand of forensic phonetic analysis, PACE would have remained a simple and transparent article of legal reform. Instead, the act exponentially increased the use of speaker profiling, voice identification, and voice prints, in order to, among other things, determine regional and ethnic identity as well as to facilitate so-called voice lineups. Emerging out of this legislation, this scientific field marked the voice as a new medium through which to conduct legal investigations.

Prior to PACE, if it was suspected that someone’s voice was on an incriminating recording—for example a bugged telephone conversation in which there was discussion of an illicit act, or a CCTV surveillance tape of a masked bank robber shouting, “Hand over the money”—that person was asked to come to the police station and give a voluntary voice sample. After PACE, doing so was no longer voluntary, and all such recordings were added to a growing sonic archive that was permanently accessible to forensic phoneticians and audiologists.

By rapidly increasing the application of forensic listening in legal investigations, PACE widened the attention of the law to include not only the voice but also many of the other sounds that constitute our sonic environment. Soon, the forensic listener was required not only to identify the voice on a recording but also the sounds in the background so as to ascertain where, by what brand of machine, and at what time of day a recording was made. PACE was the catalyst which enabled a complete spectrum of sonic frequencies to take the witness stand and testify.