It’s in the Cards

Following Oblique Strategies

Geeta Dayal

I draw a card at random from my Oblique Strategies deck. “Don’t break the silence,” it advises. I draw another card.

“Just carry on,” it tells me.

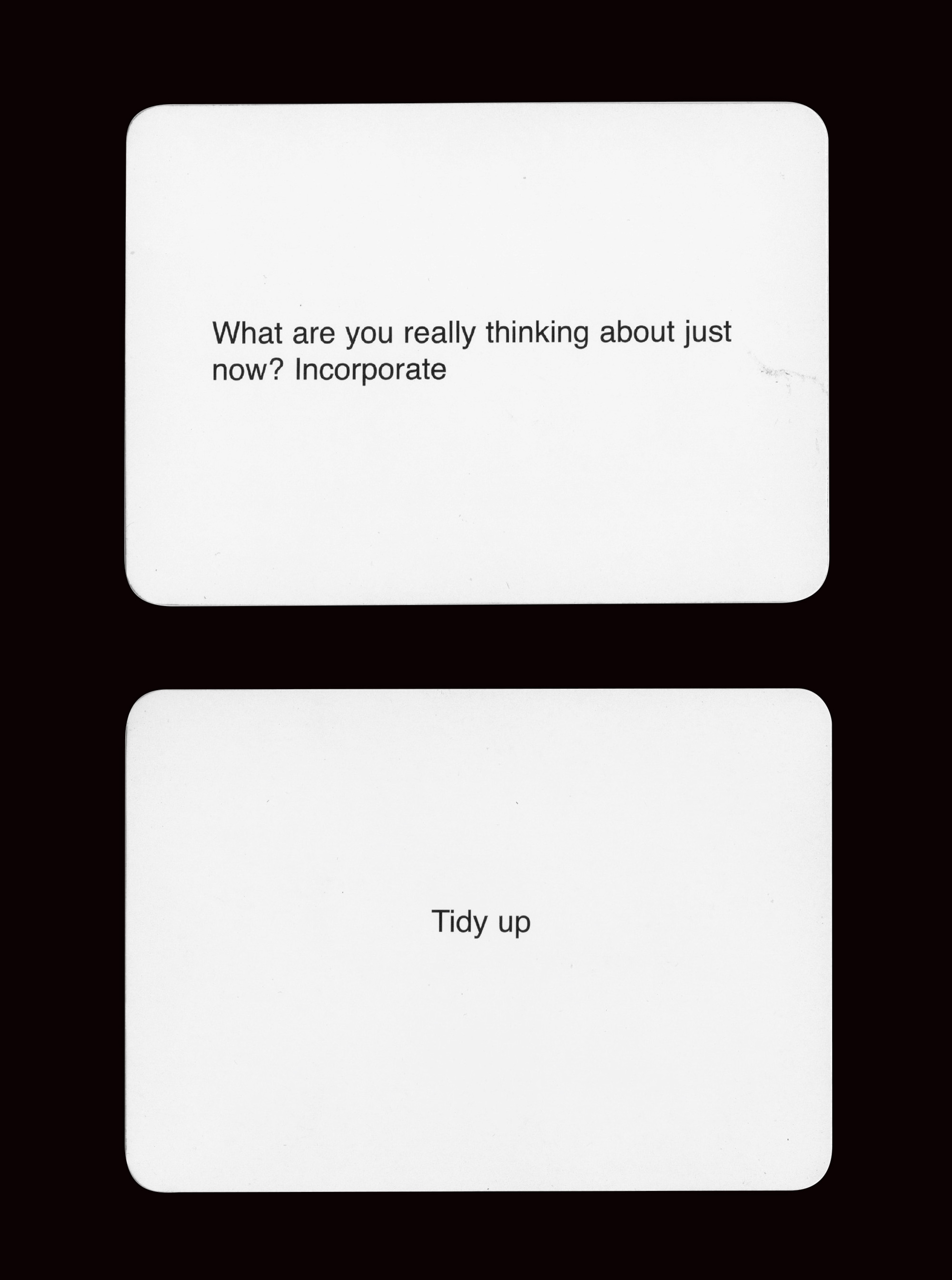

The Oblique Strategies card deck, a collection of “over 100 worthwhile dilemmas,” was originally released by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt in 1975 in an edition of five hundred copies. The first few editions of the deck—which featured clever aphorisms printed in Helvetica on white card stock with rounded edges, packed neatly in handsome cases with gold lettering—are now coveted collector’s items. These days, numerous software versions exist; there is, as one might expect, a popular iPhone app. A deck of the most recent edition of the cards, in its pleasing analogue version, retails for about fifty dollars. The cards continue to have impressive cultural traction, nearly four decades later. Many of Eno’s high-profile friends and collaborators—from David Bowie to The Edge to David Byrne—have used Oblique Strategies. The cards have been discussed by cooking magazines, Silicon Valley tech companies, international newspapers, and the Chronicle of Higher Education.

I draw another card from the deck. “A line has two sides,” it says. So it does. I choose another card. “Consult other sources -promising -unpromising.”

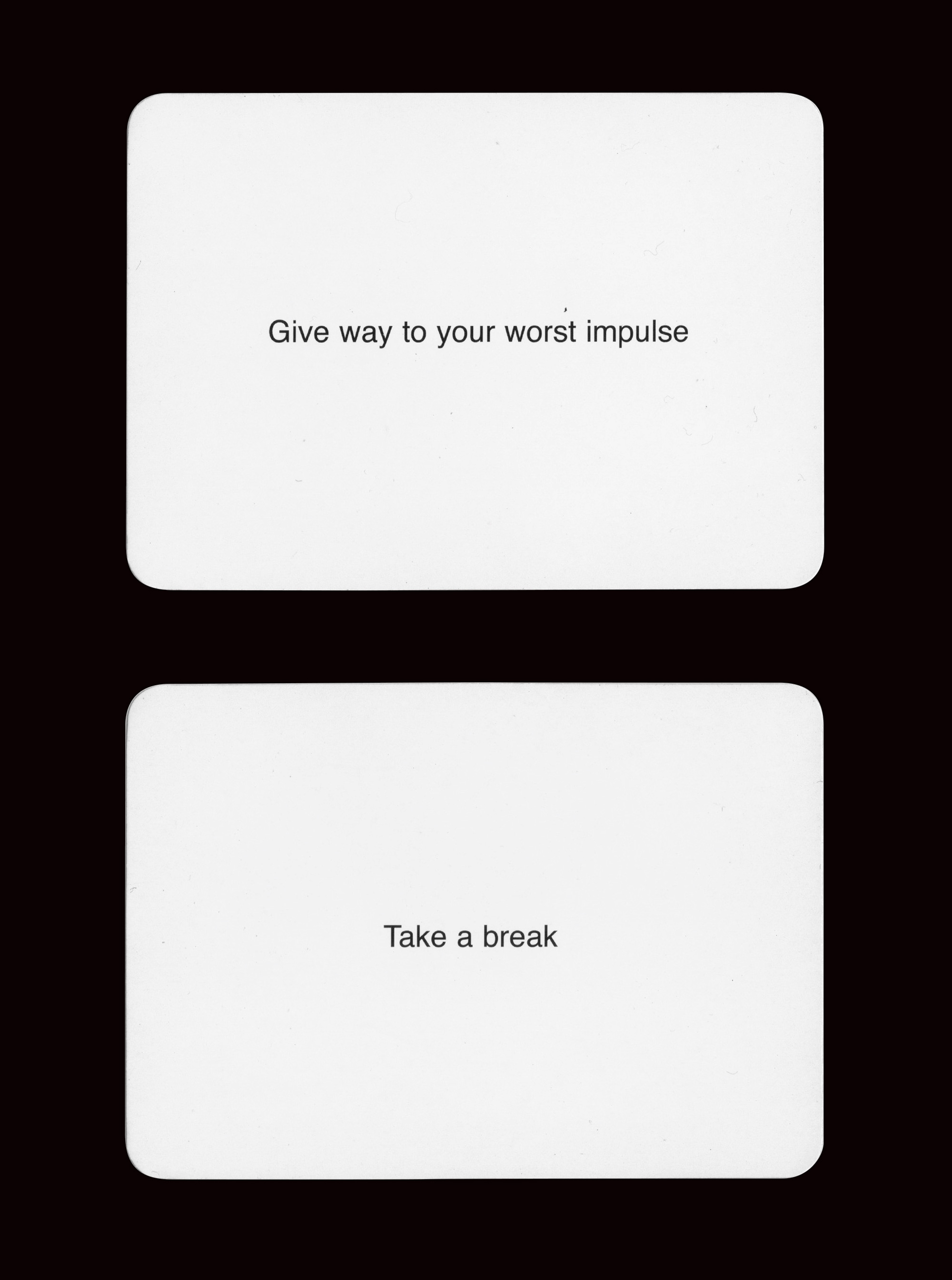

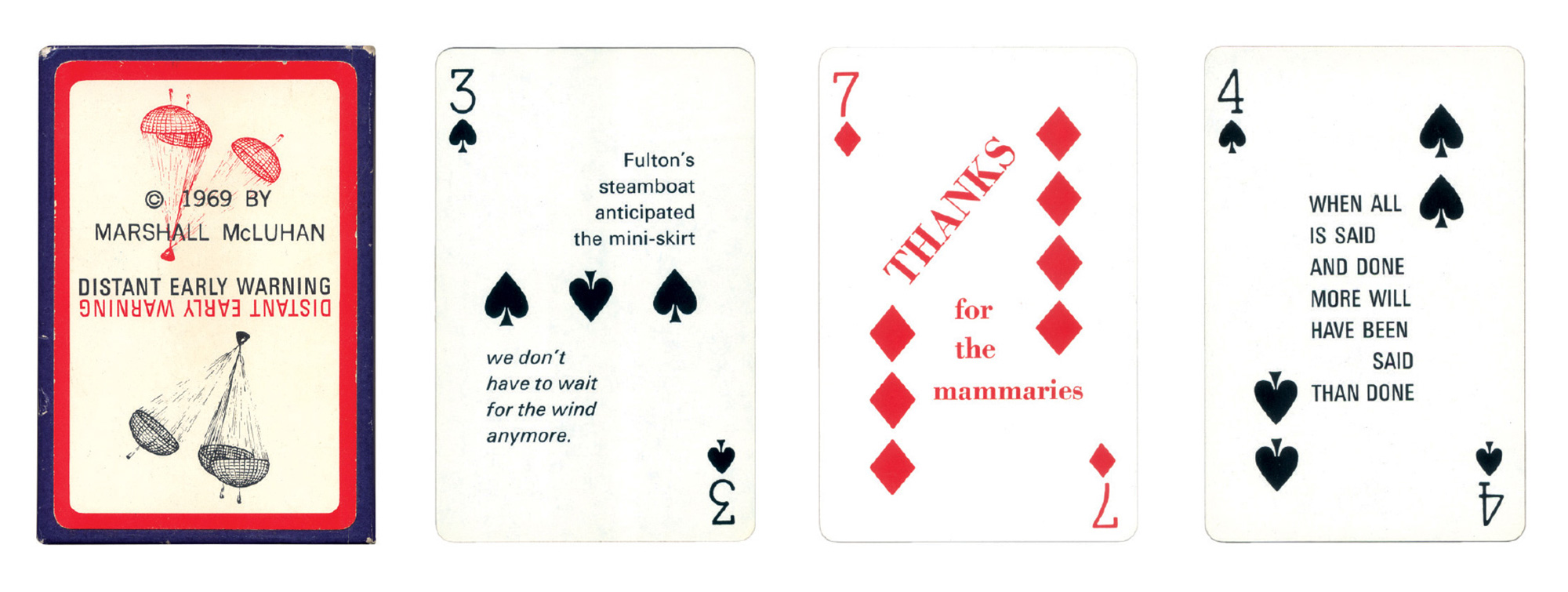

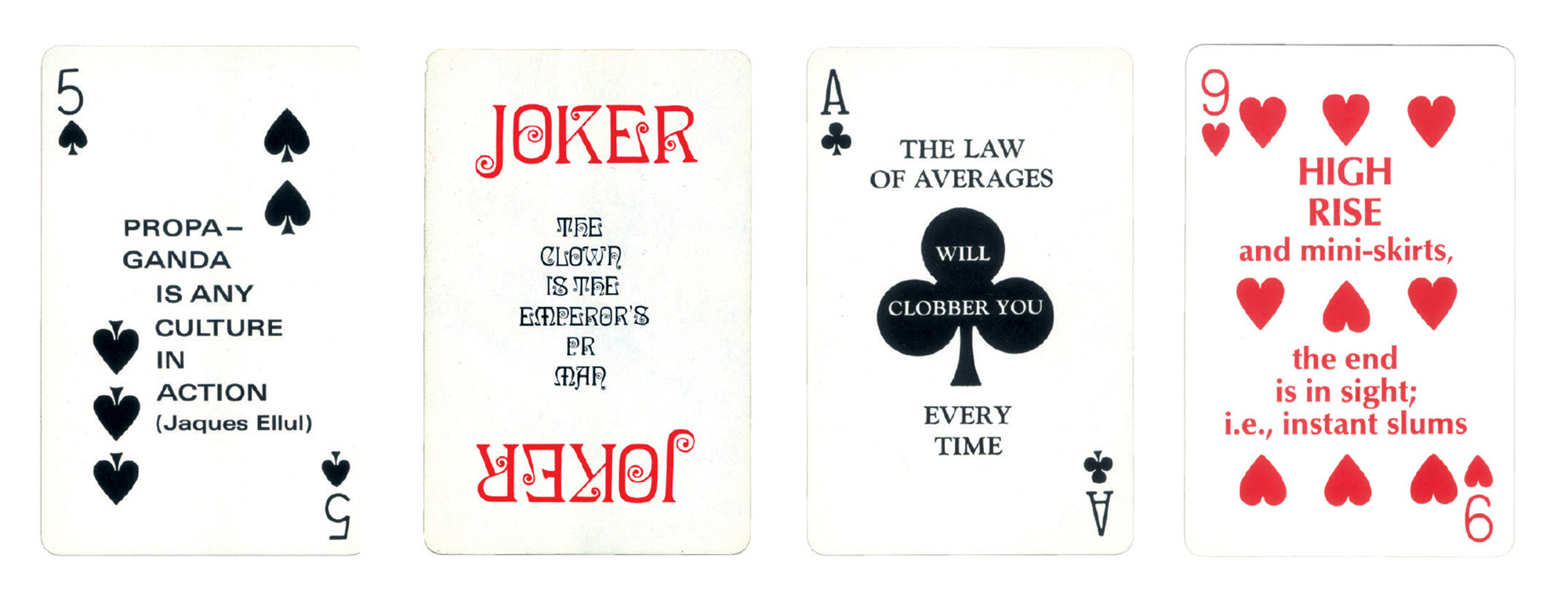

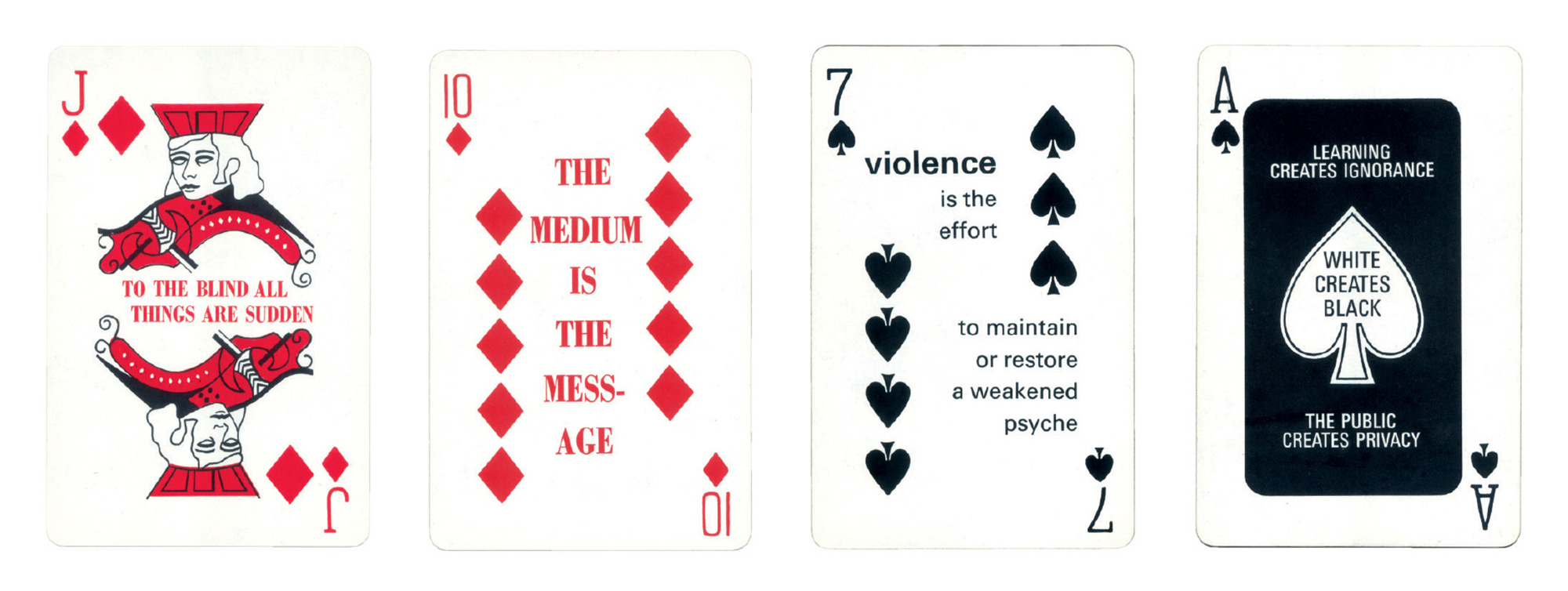

Many artists used special decks of cards or card-like systems in the twentieth century, but few of these crossed over into popular culture with as much success as Oblique Strategies. Various members of Fluxus created “Fluxboxes” and “Fluxkits” in the 1960s; George Brecht was of particular note; his piece Water Yam was a box crammed with event scores. In 1969, Marshall McLuhan released his own deck, printed on regular poker cards, known as the Distant Early Warning cards. Instead of offering specific creative advice, many of McLuhan’s cards bore quotes—some from himself (the ten of diamonds instructed “The medium is the message”) and some from others (the five of spades carried Jacques Ellul’s dictum “Propaganda is any culture in action”). Earlier on in the century, there was Aleister Crowley with his special “Thoth” tarot deck, complete with its own book, The Book of Thoth. John Cage famously used the I Ching, the ancient Chinese divination system generally based on sixty-four hexagrams—not a straightforward card deck, per se, but a complex system that he deployed in many different ways. Cage simplified the I Ching into a series of coin tosses, and adapted it to his needs, but it still wasn’t easy to use. By the end of the 1960s, Cage was asking various engineers—such as his friend Max Mathews, the director of acoustics research at Bell Labs—to write programs in FORTRAN to simulate the I Ching, generating clusters of numbers that Cage could then use to direct his compositions.

It’s hard to imagine David Bowie in Berlin in the late 1970s, strung out on chemicals and sleep deprivation, consulting the I Ching as he cracked raw eggs into his mouth for nutrition. But using Oblique Strategies—whimsical, but simple and to the point—seems a bit more rock and roll. A few classic strategies, from the first edition:

Abandon normal instruments

Accept advice

Ask people to work against their better judgement

Ask your body

Courage!

Define an area as “safe” and use it as an anchor

Discover the recipes you are using and abandon them

Don’t be afraid of things because they’re easy to do

Don’t be frightened to display your talents

Honor thy error as a hidden intention

Trust in the you of now

Looking at the strategies as a list makes one thing very clear. They are, for the most part, relentlessly positive and encouraging. Most of them offer constructive advice, and are applicable to a wide variety of situations. Some of the strategies are funny (“Look at the most embarrassing details and amplify them”); some are contemplative (“Listen to the quiet voice”); some are healing (“Get your neck massaged”). Many involve thinking about friends (“What would your closest friend do?”) or conceptualizing groups (“Use ‘unqualified’ people”) or groups of friends. In the recording studio—at least in the recording studio of the 1970s, when Oblique Strategies was developed—it was hard to be alone.

For the band Devo, who worked with Eno in the late 1970s, the cards were a turn-off. “They were too Zen for us,” complained band member Jerry Casale to the Guardian in 2009. “We thought that precious, pseudo-mystical, elliptical stuff was too groovy. We were into brute, nasty realism and industrial-strength sounds and beats.”

“Brute, nasty realism” and the elegant, crystalline compositions of Erik Satie in the early twentieth century would not seem to go hand in hand. But for Satie—an inspiration to Cage and Eno, and the father of ambient music, with his concept of “furniture music”—life was rife with brute, nasty realism. Satie was found dead in Arcueil in 1925, in a sad little room, filled with hundreds of umbrellas. Satie collected umbrellas—bunches of them at a time, in “bouquets”—ate white food, and wore velvet suits, all identical. For him, being a musician was about loneliness. “A true musician,” Satie wrote, “must be at the service of his Art … he must draw his courage from within himself … himself alone.”

Around 1912, Satie began formulating a series of increasingly bizarre performance indications—directions to the performer, inserted in the score. Normally, composers include literal, functional indications: this movement is meant to be played slowly, or, this passage is meant to be played energetically. Satie went overboard. The Mammal’s Notebook, a collection of his writings, includes some of these performance indications:

Apply yourself to renunciation

As if you were congested

Avoid any sacrilegious excitement

Be an hour late

Behave yourself, please: a monkey is watching you

Be unaware of your own presence

Bury the sound

Coldly

Courageously easy and obligingly alone

Do not come out of your shadow

Do not eat too much

Do not go out

Do not look disagreeable

Do not speak

Do not swallow

Even duller if you can

Even whiter if possible

Fall till you are weak

Flat on the floor

From a distance, bored

Hold back

Laugh without anyone knowing

Like a nightingale with toothache

Look like a fraud

Outward, painfully

Pale and priest-like

Quiver like a leaf

Slow and painful

Slow down mentally

Weep like a willow

White and immobile

With inane but inappropriate naivety

With tears in your fingers

With your bones dry and distant

With your head between your hands

“These performance indications,” writes Satie scholar Ornella Volta, “ended up developing to the point where they began to look like little stories, and charmed a number of pianists and concert organizers to the extent that they started reading them out in the course of a musical performance. This provoked the wrath of Satie. … [He] declared once and for all that ‘These indications are a secret between the performer and myself.’”

Satie’s performance indications remain, for the most part, a secret. There are no iPhone apps, no articles in popular magazines. Some of the indications are prescient and brilliant; others are humorous, or simply absurd. Many of them are desperately sad. Taken together, the indications seem like Eno and Schmidt’s strategies viewed through a cracked funhouse mirror, though many of them in fact have direct counterparts in the later deck. Satie advises us to “bury the sound”; Eno and Schmidt suggest that we “use filters,” or “remove specifics and convert to ambiguities.” Satie suggests that we “slow down mentally”; Oblique Strategies reminds us to “remember those quiet evenings.”

I draw another card—my last, I hope—and it reads: “Is it finished?”

Geeta Dayal is a staff writer at Wired.com in San Francisco. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Continuum, 2009) and writes frequently on the history of electronic music for Frieze and other publications.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.