Walter Conrad Arensberg’s Anagramania

Wordplay, madness, and modernity

William H. Sherman

While Wallace Stevens devised “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” his friend Walter Conrad Arensberg literally found billions of ways of looking at Shakespeare. Stevens’s modernist masterpiece was first published in the 1917 anthology of Others, the small magazine co-founded by Arensberg: to find the poem, we need to turn to the end of the collection—past T. S. Eliot, past Marianne Moore, past Carl Sandburg, and past the five poems by Arensberg himself that open the volume.[1] When Stevens and Arensberg graduated from Harvard in 1900, it was Walter rather than Wallace who served as class poet; and by 1916, with two books under his belt, his career was off to a promising start.[2]

Arensberg’s new poems in Others marked the most radical of departures: with titles such as “Ing” and “Arithmetical Progression of the Verb ‘To Be,’” they set out to do for the word what Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase had done for the image.[3] Indeed, they were produced between the word- and chess-games he played with Duchamp in the New York apartment where the artist had his studio and where the Arensbergs presided over the legendary salon that laid the foundations for one of America’s greatest collections of modern art—which would eventually house most of Duchamp’s oeuvre (including all three versions of the Nude) alongside world-class specimens of cubism, futurism, surrealism, and primitivism.[4]

By 1921, when the Arensbergs moved to Hollywood, Walter’s poetic project had taken another dramatic turn. Just as Duchamp stopped making art to play chess, Arensberg stopped writing poetry to play with the words of Renaissance poets. He gave up his interest in taking apart his own language and began rearranging the texts of first Dante and then Shakespeare, in an obsessive search for hidden signatures, submerged structures, and cryptographic messages that would occupy him for the rest of his life.[5] Much of Walter’s work (and his wife Louise’s money) would be channeled into the so-called Baconian cause: in pursuit of proof that Shakespeare’s plays were written by Sir Francis Bacon, the couple created the world’s largest private library of rare books by and about Bacon and gathered both their art and their books under the umbrella of the Francis Bacon Foundation. But Walter insisted that these activities were part of a larger interest in patterns that cut across time and meanings that lie beneath the surface: as he and Alfred Kreymborg put it in their motto for Others, “The old expressions are with us always, and there are always others.”

Arensberg’s early research combined Freudian symbolism and cabalistic numerology, but he soon settled on operations involving anagrams. This art of verbal transposition was one of the favorite forms of Renaissance poets: invented in the ancient world, it became for Shakespeare and his contemporaries one of their most powerful tools for concealing and revealing meaning. The rediscovery of the anagram in the nineteenth century licensed literary detectives of all kinds—none of whom would push the quest quite as far as Arensberg.[6] In his search for Bacon’s signature in Shakespeare’s works, he eventually developed such devices as the “anagrammatic acrotelestic” and the “compound anagrammatic acrostic,” a method of constructing one text from another “by arranging the letters ... in an anagrammatic sequence as an indefinite number of the acrostic letters of an indefinite number of consecutive words, beginning with either the first word or the last word of an indefinite number of lines.”[7]

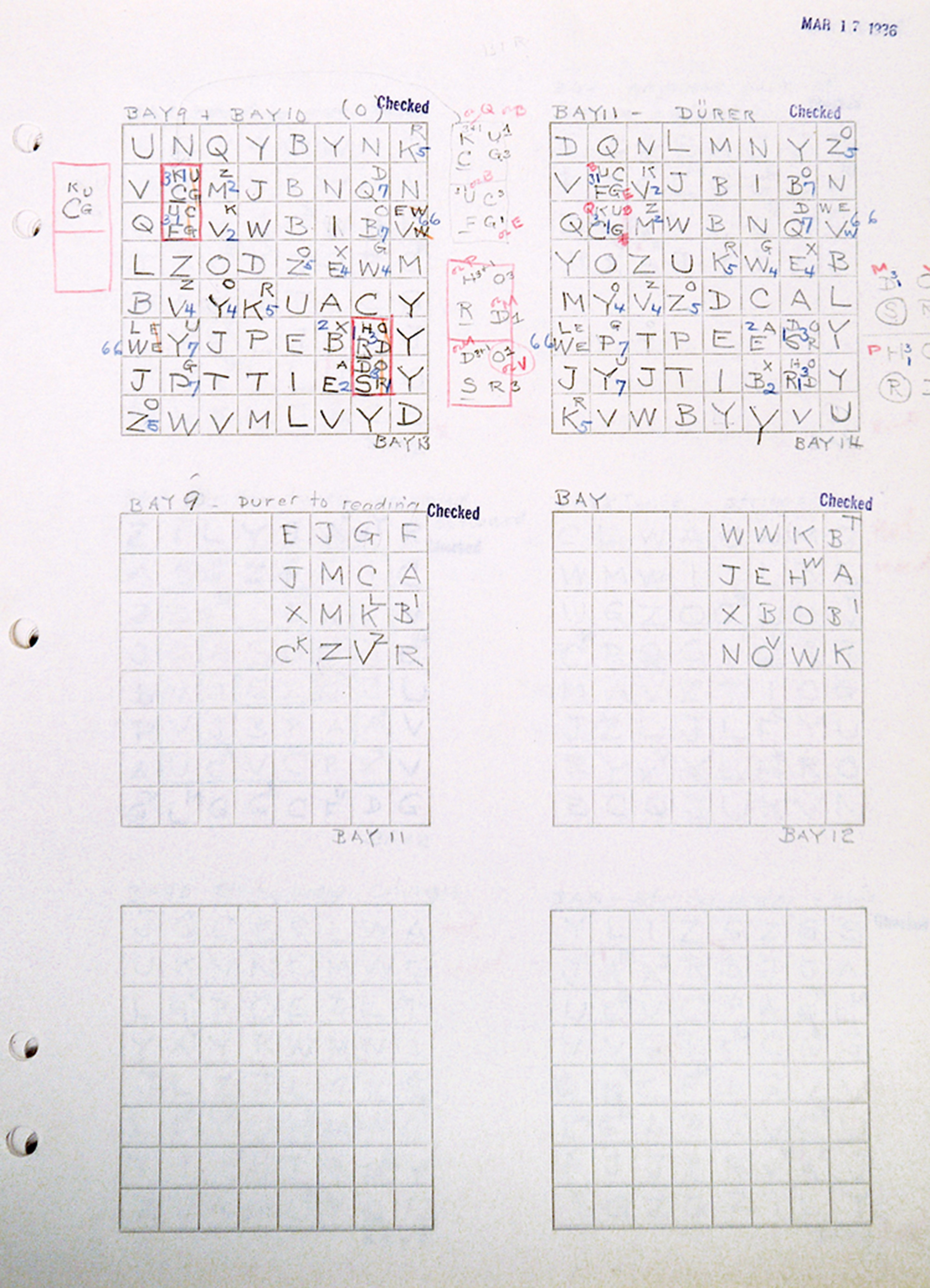

But such methods involved too much poetic license—too much room for play—to persuade the mathematical mind of William Friedman, the celebrated cryptanalyst who would become Arensberg’s chief consultant and ultimate nemesis.[8] In response to Friedman’s criticism, Arensberg developed more rigorous methods to exhaust the permutations of all 267,080 letters of Shakespeare’s First Folio (the first collection of his plays, printed in 1623)—in effect turning history’s most famous work of literature into the longest set of anagrams ever conceived.

The ever-evolving plan subjected the text to increasingly elaborate rearrangements, ranging from the fiendishly clever to the downright bizarre, involving “tetrads” and “heptads,” “locks” and “watches,” magic squares derived from Dürer, and an array of grids called chessboards. Arensberg developed so many different operations that his small team of assistants used a list of code-words to simplify his instructions: a key from 1935 included ROT for “Rotate,” PERM for “Permute,” SER for “Serial,” GRAV for “Grave diagonal,” and (of course) ANA for “Anagrammatize.” And the alphanumeric configurations became so complex that Arensberg hired a professor from Caltech to sort out the math: when Walter died in 1954, his working papers included several boxes that contained nothing but tightly rolled tapes from adding machines, each documenting one of the almost infinite routes through the Shakespearean text, and none of them producing the key to unlock the message he was looking for.

Arensberg was neither the only nor the most famous figure at the turn of the twentieth century to become an anagramaniac. Between 1907 and 1911, Ferdinand de Saussure taught his foundational “Course of General Linguistics,” which prepared the ground for a new scientific approach to language. But a search of his research notes for that project some fifty years after his death turned up a cache of 134 notebooks that revealed another, more surprising, line of inquiry. In those same years, Saussure carried out a feverish search for anagrams in Indo-European literature. Convinced that hidden alphabetical patterns offered the key to a lost structural code in Latin, Greek, and Vedic poetry, he eventually filled twenty-four books with possible anagrams from Homer and another nineteen with notes from Vergil. The more he looked, the more he found; but instead of confirming his hunches, this proliferation of evidence unsettled him and led him to “wonder if one might not find definitive proof of all possible words in any text.”[9] Saussure found himself relying upon a sense of intuition that he never fully trusted and, suffering from what he described as “a morbid horror of the pen,” he finally set the project aside without publishing any of his findings. For some later linguists, these experiments were an episode of dementia that is best forgotten. For others, they were the necessary extension of his orthodox work, serving as inspired glimpses of poetic meaning that pointed to different rules—and perhaps even different games—for language.[10]

Walking the line between the playful and the providential, and exploring the boundary between method and madness, the anagrammateur is tireless in his discovery of the new words that lie hidden within old words. As the ultimate instrument of the possible, the anagram is ideally suited to the perception of hidden patterns but rarely able to serve as evidence of intention or origin. Working with anagrams is more like playing a game than arriving at a proof, as Friedman observed when he visited Arensberg for one last time in 1951:

At this moment it strikes me that he has subconsciously selected or hit upon a method which can only continue him in his delusion. He subconsciously knows, I believe, that his quest is hopeless but his system is such that for the rest of his life he can continue with the method, never finding positive proof—but never excluding the possibility that by continuous modification of his “alphabet” ... good plain text ... will be found. The whole business is most curious and well worth writing up in psychiatric annals.[11]

One way of looking at Walter Conrad Arensberg suggests a tragic waste of time, money, and talent; but if we rearrange the picture, we see a man who found a way to play chess with Bacon, and Duchamp, in a game that would never end. And just as Saussure’s legacy is split between his scientific work and its irrational shadow, Arensberg left behind a museum filled with masterpieces and an obscure archive stuffed with outsider art by one of the art world’s great insiders.

- Alfred Kreymborg, ed., Others: An Anthology of the New Verse (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1917). See also Suzanne W. Churchill, The Little Magazine Others and the Renovation of Modern American Poetry (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006), and Glen G. MacLeod, Wallace Stevens and Company: The Harmonium Years, 1913–1923 (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1983).

- Poems and Idols were published in 1914 and 1916, respectively, both by Houghton Mifflin.

- In 1969, Kenneth Rexroth suggested that “Gertrude Stein and Walter Conrad Arensberg both went further than anyone ... in applying the methods of Analytical Cubism to poetry.” See Bradford Morrow, ed., World Outside the Window: The Selected Essays of Kenneth Rexroth (New York: New Directions, 1987), p. 257.

- Francis M. Naumann, New York Dada, 1915–23 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994), and “Walter Conrad Arensberg: Poet, Patron, and Participant in the New York Avant-Garde, 1915–20,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin, no. 76 (Spring 1980), pp. 2–32; Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, “Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Silent Guard’: A Critical Study of Louise and Walter Arensberg” (unpublished PhD dissertation, UCSB, 1994), and “Sex, Alcohol, Soufflés, with Chess, Accompanied by Music,” in Martin Ignatius Gaughan, ed., Dada New York: New World for Old (New Haven: G. K. Hall, 2003).

- For a start, see Arensberg’s The Cryptography of Dante (New York: Knopf, 1921) and The Cryptography of Shakespeare (Los Angeles: Howard Bowen, 1922).

- William H. Sherman, “Of Anagrammatology,” English Language Notes, vol. 47, no. 2 (Fall–Winter 2009), pp. 139–148.

- Walter Conrad Arensberg, The Cryptography of Shakespeare, op. cit., pp. 202–203.

- See my essay for Cabinet no. 40 (Winter 2010–2011), “How to Make Anything Signify Anything.”

- Jean Starobinski, Words upon Words: The Anagrams of Ferdinand de Saussure, trans. Olivia Emmet (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), pp. 100–101.

- Jonathan Culler, Framing the Sign: Criticism and its Institutions (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988); Jean-Jacques Lecercle, The Violence of Language (London: Routledge, 1990).

- Friedman’s diary for his trip to Hollywood in December 1951 is Item 881 in the Friedman Collection at the George C. Marshall Foundation in Lexington, Virginia.

William H. Sherman is professor of English at the University of York. He is writing a book about Walter Conrad Arensberg and William F. Friedman, and working with Mark Nelson on a reconstruction of the art and book collections at the Arensbergs’ Hollywood home.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.