A Case for Darwin

Henry Flower’s evolutionary displays

Rachel Poliquin

In 1888, a large four-sided glass display case containing four dozen albino animals and birds was installed in the Central Hall of the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, London. Among its ghostly occupants were a wallaby, two rabbits, a hedgehog, a lobster (pale but not purely white), a mole, a squirrel, and more than two dozen birds, including a rook, a pied-headed blackbird, and a sparrow with pink eyes. Most of the birds were perched on the branches of a leafless tree sprouting through the center of the case. A few were posed fluttering as if about to take flight, while the animals were arranged around the base, staring out at visitors from all four directions. Accompanying the display was an explanatory sign describing albinism as “a condition in which the pigment or colouring matter usually present in the tissues constituting the external covering of the body, and which give them their characteristic hue, is absent.”[1]

With or without its pedagogical value, the display captivated visitors. The newspapers of the day heralded the case as one of the most popular in the whole museum. As the Daily Chronicle wrote in 1891, “apart from its scientific value, the collection is certainly an oddly attractive one, and it is no wonder so many visitors linger round it,” particularly the younger children who “will even try to kiss the white ones, forgetting the glass.”[2] But the display was hardly a straightforward illustration of biological fact. Artistically arranged, the display seems innocuous, scientifically speaking, and yet, while there is nothing controversial in describing and illustrating albinism, the case was part of a strikingly original educational series that used animal charisma in the service of scientific propaganda.

The albino display was the third case in a series of seven created by Henry Flower, the director of the Natural History Museum. The Central Hall was the first space visitors encountered when entering the museum, and Flower wanted to fill the hall with introductory lessons illustrating “general laws or points of interest in Natural History”[3] which did not fall within the taxonomic principles governing most of the museum’s zoological collections. Row after row of animals systematically arranged by genus and species were highly illustrative, but the ordering principle excluded discussions of any other laws or natural facts such as albinism or, more provocatively, natural selection. Installed in the vast, cathedral-like hall between 1887 and 1891, Flower’s educational series was significantly positioned to illustrate not just any laws or points of interest but the full complexity of one spectacularly polemic doctrine: evolution.

• • •

Although the basic idea of evolution—that all existing life forms are derived from earlier forms by a process of descent with modification—was generally accepted by the end of the nineteenth century at least for organisms other than humans, how evolution occurred remained under debate. (Surprisingly, even Thomas Henry Huxley, one of Charles Darwin’s fiercest supporters, was never quite convinced of natural selection.) As Flower remarked to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1889, since its first publication in 1859, Origin of Species had ignited “no little controversy as to how far all the modifications of living forms can be accounted for by the principle of natural selection. .... It certainly cannot be said that in these later times the controversy has ended.”[4] As a naturalistic, non-directional, and non-teleological explanation for evolution, natural selection was one of Darwin’s most innovative contributions to biology, and also the most contentious.

Darwin had written Origin to appeal to a broad audience. However, among the non-scientific community, the book was not as widely read as Darwin had hoped. Nature books with a traditional message of natural theology and divinely ordained diversity were far more popular. For example, John George Wood’s Common Objects of the Country, published the year before Origin of Species in 1858, had sold 86,000 copies by 1888. A decade later, Origin had still only sold 56,000 copies. As for Darwin’s popularizers, many avoided or denied outright the controversial subject of natural selection. Some more religiously minded Darwinian popularizers such as Henry Drummond even suggested that evolution was nature’s mighty striving for amelioration and unfolded according to a divine plan. Consider, for example, that Drummond’s Natural Law in the Spiritual World, published in 1883, sold an extraordinary 120,000 copies in just seventeen years, almost three times more than Origin had sold in four decades. But whatever the community or controversy, debates over evolution and natural selection were textual, abstract, and theoretical. Evolution could not be demonstrated or “proven” in a laboratory in the same way as gravity or laws of motion. What Flower offered visitors in his education series were erudite visual demonstrations of natural selection. Moreover, he offered them to the thousands of men, women, and children streaming through the museum every year—nearly ten thousand on a single holiday Monday in 1893—and it was for all those eyes, hearts, and minds that Flower designed his exhibits. Prominently positioned in the main entrance hall, the cases offered clear-eyed visions of evolution at work.

• • •

The first display was installed in 1887 and illustrated hybridization in the wild. A series of goldfinches were arranged on a large scraggy branch. A carrion crow, a hooded crow, and crossbreeds between the two were positioned below. The label explained that carrion crows (pure black) inhabit lands west of the Yenisei River, while hooded crows (black with white breasts and backs) are native to forests east of the river. The river likewise divides the territories of the European and Himalayan goldfinches. As the birds were all collected along the banks of the Yenisei River, the specimens clearly demonstrated that, where their ranges overlap, the species where able to interbreed and produce hybrid offspring with intermediate coloration. “Both these examples may by some naturalists be considered instances, not of crossing of distinct species, but of ‘dimorphism,’ or the occurrence of a single species of nature under two different outward garbs; but from whatever point of view they are regarded, they illustrate the difficulty, continually increasing as knowledge increases, of defining and limiting the meaning of the ‘species,’ of such constant use in biology.”[5] The underlying meaning is simple: a species is not a fixed, divinely created form of creaturely life but a shifting, adaptable entity that could take various forms and colors. Most importantly, visitors could see the animal proof for themselves. The hybrid young crows were mottled with splotches of black and white, combining features of both pure-bred parents, and the goldfinches displayed many color graduations.

The second display installed just a few months later was a greater triumph for its sheer aesthetic appeal. Exhibiting more than thirty breeds of fancy pigeons, the display offered visitors a three-dimensional diorama of a Victorian dovecote. Large ornate breeds were positioned around the base of a pole-mounted dovecote while a pair of wild rock pigeons—the ancestor of all fancy pigeons—was positioned as if flying above. The bottom of the case was strewn with straw, and a wicker basket, perhaps filled with feed, was included as an additional atmospheric prop.

From a scientific perspective, pigeon breeding was an obvious choice for Flower’s series. In his research into heredity, Darwin had given particular attention to pigeons, going so far as to set up a pigeon coop in the back of his garden at Down House in 1855. He bought birds from premier poultry dealers, communicated with breeders, and joined their pigeon clubs. At the peak of his pigeon passion (by 1861 he had moved onto orchids), Darwin had almost ninety birds, including some particularly rare and fancy breeds. His research led him to use pigeons as a special study group in Origin and dedicate two chapters of The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868) to pigeon studies.

The long history of breeding domesticated animals for desired traits was crucial in the development of Darwin’s theories. In fact, the analogy between natural selection and human (or artificial) selection was central to his thesis. As he wrote in Origin, by examining the modification of domesticated plants and animals by selective breeding, “we shall thus see that a large amount of hereditary modification is at least possible; and ... we shall see how great is the power of man in accumulating by his Selection successive slight variations. I will then pass on to the variability of species in a state of nature.”[6] Darwin presumed that many of his readers would be familiar with the means and methods of animal breeding. From such commonplace artificial selection, Darwin hoped his readers would see the logical step to natural selection in the wild. Likewise Flower hoped his pigeon display would encourage the visitors along the same logical lines of thinking.

But what made the display successful was not its explanation of the science of breeding, but the appeal of the pigeons themselves. Pigeon fancying was hugely popular in the nineteenth century, perhaps even more popular than that other iconic Victorian pastime, bird watching. Inexpensive and easy to breed, pigeons were also small and required little space and attention. Thousands of pigeon coops were constructed in gardens across Britain, from Queen Victoria’s dovecote at Windsor Castle to small coops kept by even the poorest Londoners on rooftops. Even within the most modest of accommodations, pigeons enchanted breeders with their extraordinary possibility. A frillback’s curly feathers, the outlandish hood of the Jacobin, a pouter’s ballooning chest, the wattles, crests, laughing calls, feathered feet, and beaks—Victorians were obsessed. Pigeon fanciers formed clubs across Britain and filled their social calendars with major exhibitions and competitions. By the mid-nineteenth century, more than 155 distinct morphs were recognized, more than any other domesticated animal, including dogs.

The displays’ prominent position ensured that visitors encountered them when entering and leaving. Perhaps they had to wait for a companion, and so passed the time by examining the series. Designed in the round with four glass sides, the cases also encouraged longer, more active looking as visitors had to walk around the case in order to see each of the animals. Yet, despite any amount of attention to an exhibit’s construction and design, visitors can never be forced to look. Only the excessively conscientious museum-goer will study each exhibit in turn, reading each label, noting each feature that distinguishes one species from another. Most visitors are hardly so diligent. Most will wander among the hallways and corridors, breezing by some displays, pausing to study others. What stops the museum meander is rarely the explanatory text but rather the animals themselves: a display’s pedagogical power arises from the visual appeal of the creatures on view. In other words, it is hardly irrelevant that Flower’s pigeons were all prize-winners. The yellow dragoon won first prizes at both the Crystal Palace and Birmingham shows. One of the satinettes won best of its class at the Albert Palace, Worthington, and Bristol exhibitions. The almond tumbler, white Jacobin, Russian trumpeter, blue frillback, and blue-laced blondinette were all prize-winners and most notable specimens of their breeds. Many visitors may have come to the museum simply to see the pigeons.

• • •

The first three cases on dimorphism, selective breeding, and albinism offered proof of spontaneous change and transformation. Representing “sports” of nature, the albino animals reminded visitors that mutations do occur in the wild, and that such alterations are not always improvements or beneficial to the species (an argument against a progressive view of evolution). The hybrid crows showed that crossbreds and multiple forms occur in the wild, without human intervention. And the pigeons make beautifully clear that extraordinary new forms are possible, given the right pressures. Taken together, the cases opened the possibility that over generations not only new forms and new coloring could arise, but even entirely new species. And most impressively, the theories were illustrated so that all visitors, even children, could discover the laws for themselves.

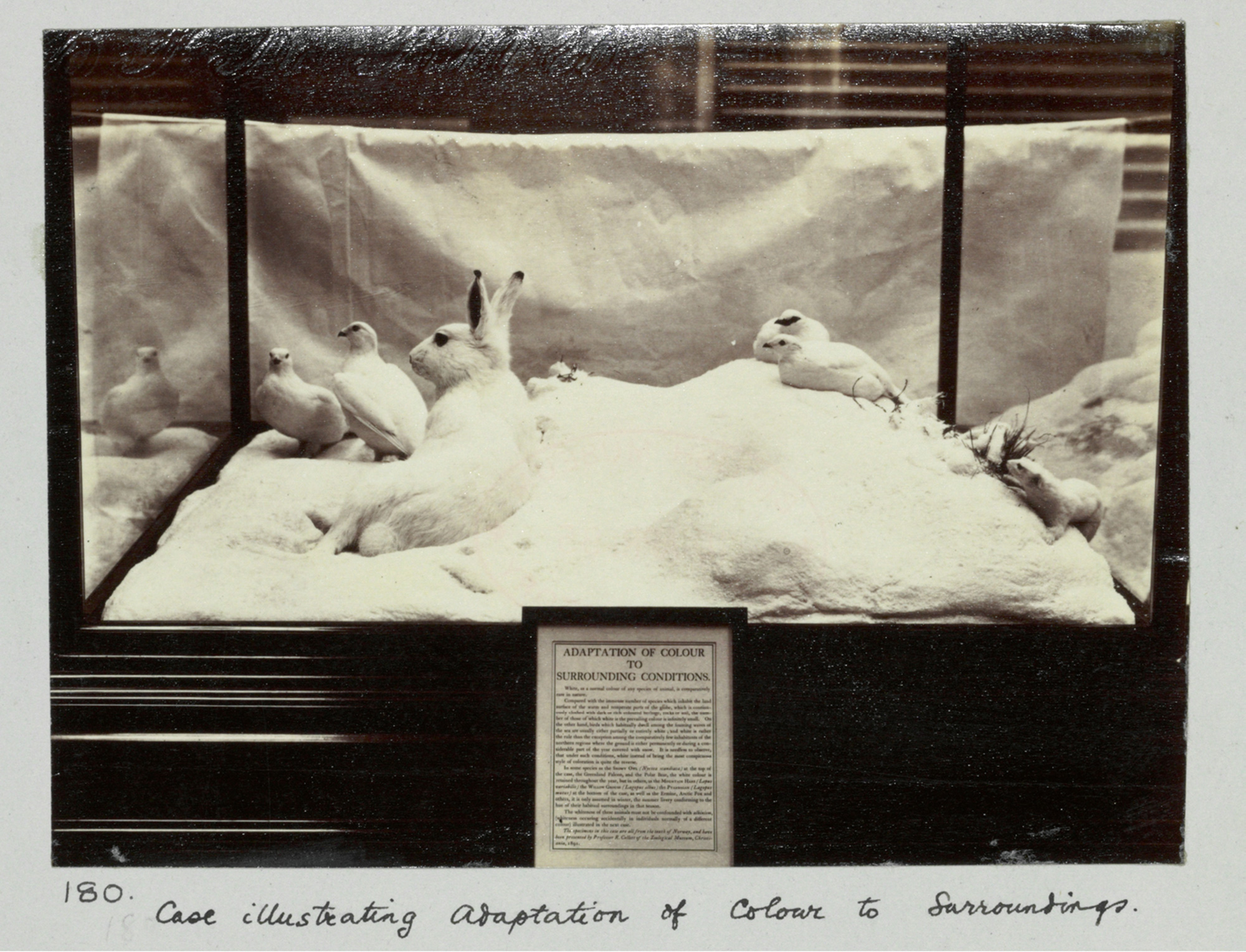

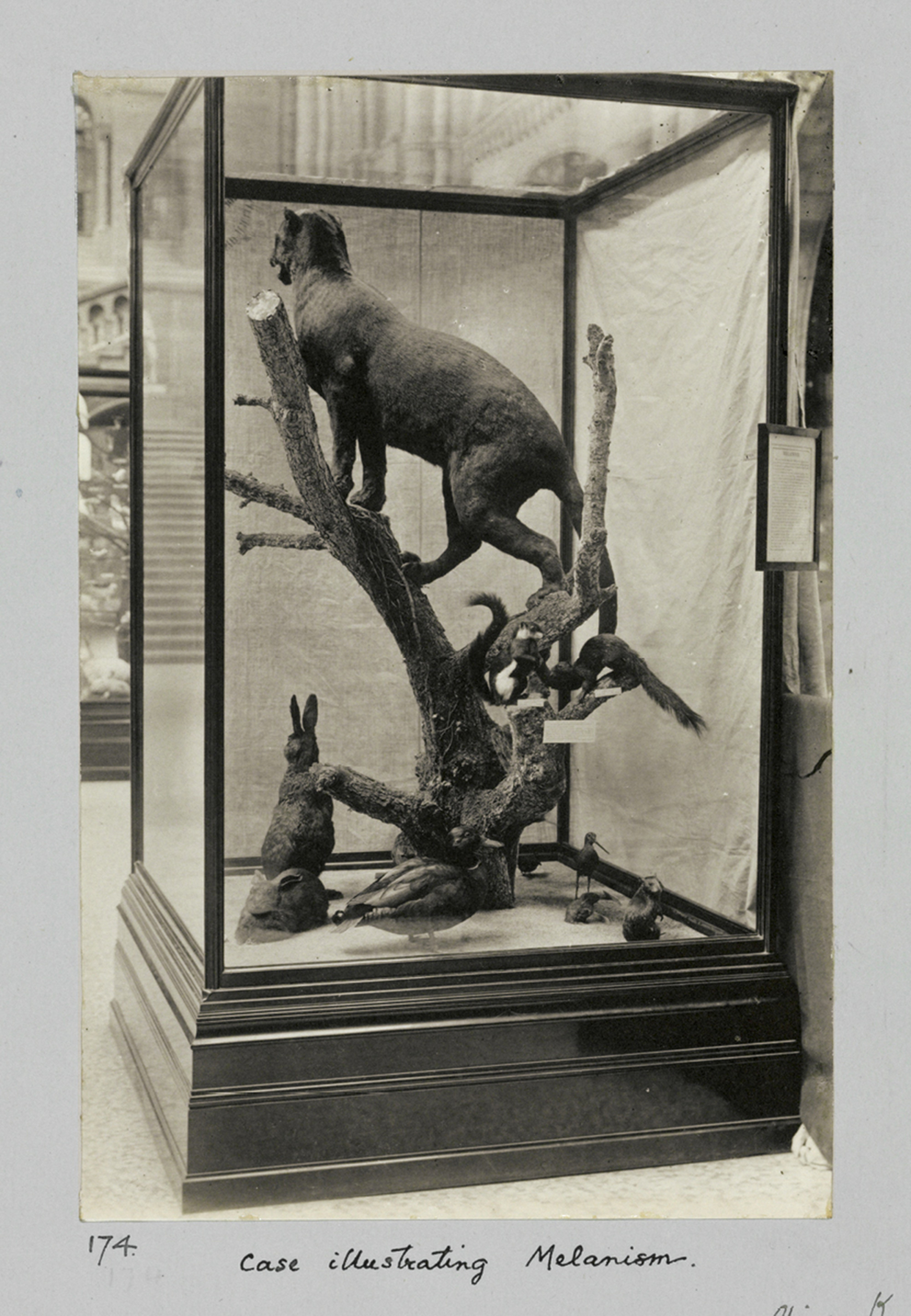

By 1891, the series was completed with four additional cases: protective mimicry, adaptation to environment, external variation according to season and sex, and melanism or excess pigmentation. Newspapers universally swooned over the displays. The Morning Post described the cases as “an unmistakable delight to children” and “fairy tales of science.”[7] Here was science made palatable to the ordinary visitor who probably had not read Darwin. “Needless to say,” the popular journal Land and Water wrote, “the mounting of the animals is perfect, and such ‘exhibits’ will do more to popularize and stimulate an interest in natural history than rows and rows of dismal specimens mounted upon the regulation stands.”[8] Even better, here was theory made animal. For example, the case exhibiting seasonal variation was divided into two levels in order to showcase the same animals (an Alpine hare, a ptarmigan, a willow grouse, a stoat, and a weasel) in their “summer dress” of browns and grays and again in their white winter coats. Both scenes blended the animals with their habitats—white on pure white (faux) snow, mottled browns on lichens, moss, and rocks. Hardly a dry lesson in selective adaptation, visitors themselves could test the harmony between the coloration of animals and their surrounding by standing back or coming up close. Similarly, the display on protective mimicry hid insects among the flora they had evolved to resemble: it was the visitor’s job to find the grasshoppers on the rocks, locusts among the leaves, or the “dead leaf” butterflies on the twig. As one journalist for The Daily Chronicle remarked in 1891, “It is amusing to hear visitors trying to count how many butterflies there are on the twig. Few hit the number right. It would spoil the fun to mention how many there really are.” That protective mimicry occurs “the facts show,” the journalist continued, and “that the chances of ‘survival’ are thereby increased seems self-evident. What the real explanation of it all is is a question that, at the present time, is receiving much attention. The facts alone, however, independent of any theory, are of a highly attractive nature.”[9]

As one of the clearest, most visual, and most accurate nineteenth-century popularizers of Darwin’s theories, Flower understood that lessons should not only be comprehensible and engaging but also focused on the animals themselves. Like Darwin, Flower believed that animal beauty was hardly irrelevant and that the success of any lesson in natural history depended on the particular and personal appeal of the animals under discussion. In designing his educational series, Flower hoped that animal charisma would charm viewers into looking long enough to see the truth of Darwin’s work for themselves. And, in that, he was successful. “The cases appear to be the most popular in the whole museum,” The Daily Chronicle continued, “for, partly perhaps from their prominent position and partly from the interesting forms they contain, they always attract much attention, and that too from visitors who probably have not read Darwin. Here, however, they can see the facts for themselves, and there is much for those previously unacquainted with the subject to cause wonder.”

- Quoted in “Saturday Afternoon VIII: At the Natural History Museum, Cromwell-Road,” Pall Mall Gazette, 22 February 1890.

- “Illustrations of Darwinism,” The Daily Chronicle, 19 May 1891.

- William Henry Flower, A General Guide to the British Museum (Natural History) (London: British Museum (Natural History), 1891), p. 23.

- William Henry Flower, “Museum Organisation,” in Flower, Essays on Museums and Other Subjects Connected with Natural History (1898; Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1972), p. 24.

- Flower, A General Guide, p. 22.

- Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (London: Penguin Books, 1968), p. 67.

- “Cromwell-Road Museum,” The Morning Post, 25 September 1891.

- Richard Lydekker, “A Winter and A Summer Scene in Norway,” Land and Water, 9 April 1892.

- “Illustrations of Darwinism,” The Daily Chronicle, 19 May 1891.

Rachel Poliquin is a Vancouver-based writer and curator. She is the author of The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing (Penn State University Press, 2012) and ravishingbeasts.com [link defunct—Eds.], a website dedicated to all things taxidermy. Her curatorial work includes “Ravishing Beasts: The Strangely Alluring World of Taxidermy” (2009–2010) at the Museum of Vancouver and the permanent vertebrate exhibits at the Beaty Biodiversity Museum.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.