Dream House

The maple at Matibo, or, the maple at Ratibor

Paul Maliszewski

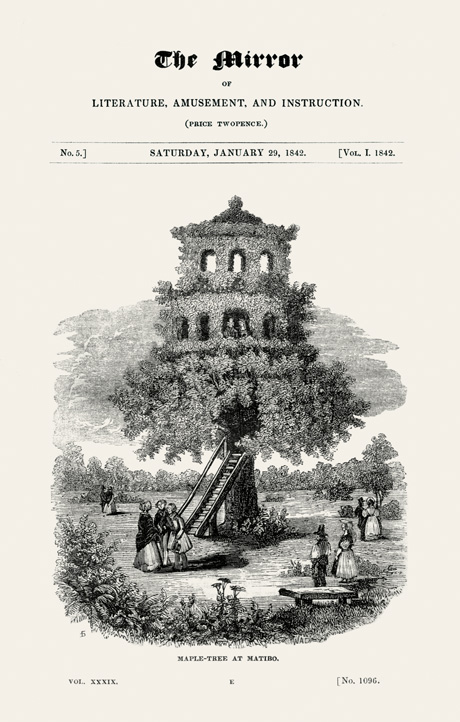

The day before my wife and I got engaged, we stopped by an antique print store in Asheville, North Carolina. I was flipping through a binder of tree-related items when I came across an engraving of a two-story tree house. Attached to the trunk of the tree was a staircase that led up to an opening concealed by shadow. Above it, the branches and leaves had been sculpted into round rooms with arched windows. A couple stood framed in the center window, the man in a top hat, the woman wearing a scarf or veil. They were looking out, or perhaps down—the engraving was only so detailed. On the ground below, couples milled about, while three people chatted at the bottom of the stairs. “Maple-Tree,” the caption read, “at Matibo.” Where in the world, I thought, is that?

I slipped the engraving out of its plastic sleeve. It was printed on the front of the January 29, 1842 issue of an English periodical called The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, price twopence. While the current cost was steeper, I opened it and read a two-paragraph item which explained that the tree was “one of the most curious ornaments of a charming estate, called Matibo, situated in the neighbourhood of Savigliano, in Piedmont.” At the time of publication, the tree was more than sixty years old, but it had been only twenty-five or thirty years since work began, giving it “the form of a temple.” More description followed, evocative details about the floor (“formed of branches twined together with great skill”), the furnishings (“leafy carpets”), and part-time residents (“innumerable birds have taken up their sojourn”). All very poetic, though vague. Whose skill, after all, had fashioned the branches into floors? And who owned this charming estate? The article, alas, ended there, with delighted visitors looking out the windows, admiring “the prospect which opens to their view.”

I looked through the rest of the issue, but saw nothing further about the tree house and so slid The Mirror back into its sleeve and returned the binder to its place. We bought a print that day from an eighteenth-century encyclopedia, but I continued thinking about the tree house. Upon returning home, I looked it up online, trying what I recalled of the few specifics. Then I just broke down and wrote the owner of the store to purchase the thing.

For the next six years, I searched off and on, seeking more information about the Matibo tree house. I was never that dogged. I worked on other projects, until something reminded me of the engraving or it rose up, unbidden, from my memory, and then I plugged the usual keywords into Google and various library databases, but with little luck. I wondered if the tree was a brilliant fiction. Occasionally, I found someone who had posted a jpeg of my engraving (or one similar to it). Just the picture, though, with no further information save what could be gleaned from the print itself—the caption, the publication’s name, perhaps the year. The tree house was like a photo pinned to a bulletin board, a way to say, “I like this,” and then say nothing more.

In 2012, however, I stumbled upon the work of two fellow enthusiasts, Susan Rhoads and Bill Thayer. Their story, detailed in “The Matibo Affair, or, Your Cheating ’Art,” began with Rhoads’s discovery of an engraving in the December 1841 issue of Le Magasin Pittoresque, published a month before The Mirror.[1] Rhoads, a physician based in Kentucky, was teaching herself French, and Thayer, a translator who had built a website with 11,000 pages of information covering everything from Roman antiquity to a sixteen-month-long excerpt from his diary, had agreed to help.

Together, they traced the circuitous path taken by the tree house engravings. Appearances in Le Magasin and The Mirror were just the beginning. The Mirror’s write-up was, it turned out, a faithful, though not-credited translation of Le Magasin’s own. Rhoads and Thayer were off, in search of other plagiarists and copyright violators. They found the tree house in Robert Merry’s Museum, an American publication that for some reason made Matibo an island; in the Spanish-language magazine La Colmena; and in a Portuguese article about the world’s greatest trees.

Then, in 1893, the tree moved. It was now growing, according to London’s The Picture Magazine, “on the left bank of the River Oder.” “The Maple-Tree of Matibo” had become “The Maple of Ratibor,” referring to the town then in Germany and now in Poland. The story was picked up next by Garden and Forest Magazine in 1894, whose note on the transplanted tree house was then reprinted, Rhoads and Thayer discovered, in 2000 by the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, in their quarterly journal.

Through every twist of the story, Rhoads and Thayer kept after the unscrupulous publishers. What I wondered, though, was not “How dare those thieves?” but rather, “Why this engraving?” Of course, copyright then was more a well-meaning concept than an actual business practice. If a publisher could steal anything, fobbing it off as his own, what did it mean that this picture was stolen so often and for so long?

The tree-house engraving, in whichever of its several, slightly differentiated guises, is a picture of innocence, sweetness, romance. It’s also a depiction of spring—the tree is full, flowers dot the greenery in the foreground, and the people look lightly dressed, a thin shawl on a woman, no heavy coats. For winter-bound readers of Le Magasin and The Mirror, it was a picture full of warmth and longing. Then there’s that couple in the window. Were they just married or engaged? Perhaps I was too inclined to read my life into the engraving, pasting myself into the tree, proposing there, marrying, celebrating, but then The Mirror does say the tree was given “the form of a temple.” The engraving, finally, offers the possibility of another sort of existence: people in trees. It seems so appealing, easy, without worry. Maybe, if things were different, we could live like that.

Then Thayer made an exciting discovery: in 1837, the Repertorio d’agricoltura reprinted an article by Marquis Lascaris of Ventimiglia, crediting his annual agricultural review, Calendario Georgico. It was the earliest report they’d found about the tree house, and the first from Italy. The tree house was real, not some fancy concocted to gin up magazine sales.

Still, there were so few references to Matibo, and the estate was only mentioned in conjunction with the tree house. Rhoads then found a press release on the website of Luigi Botta, who ran for mayor of Savigliano in 2004. A party for his supporters was held, it said, at a historic residence located near “the Matibo that once had the famous maple of Savigliano transformed into a two-story building.”

I contacted Botta. Matibo, he said, was real. The area, not far from the river Maira, was mainly agricultural, but it “has changed dramatically ... and is now virtually annexed to the city.” He added, “The house, the one that was mentioned in the texts, is no more.” There was proof, too. Botta showed me a map from 1879 on which “Mattibo” appears, the extra t a quirk, apparently, of the mapmaker, and then another map, from 2004. Matibo, or Mattibo—sometimes, in the early accounts, it’s Matibó—is there, marked. Botta also sent two documents about ecology, each with an engraving of the tree house, one I’d never seen. In it, a woman is alone in the window, and a man is walking down the stairs looking toward a couple at the bottom. The stairs here slope to right, unlike in every other engraving, and I was so taken by that new angle I nearly overlooked the other man, up on the second story. He blends in with the branches, like he’s part of the tree. Then I realize there’s a patio up there, maybe a walkway. It’s curious, this engraving, ambiguous, too, like a mystery only half-solved.

- Rhoads and Thayer’s investigation is available at www.elfinspell.com/FrenchTexts/MagasinPittoresque/Vol-9-1841/L-ErableDeMatibo-English.html.

Paul Maliszewski is a writer in Washington, DC. He is the author of Fakers (The New Press, 2009) and Prayer and Parable (Fence Books, 2011).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.