Forensic Topology

The bank burglar as urban planner

Geoff Manaugh

In the 1990s, Los Angeles held the dubious title of “bank robbery capital of the world.” At its height, the city’s bank crime rate hit the incredible frequency of one bank robbed every forty-five minutes of every working day. As

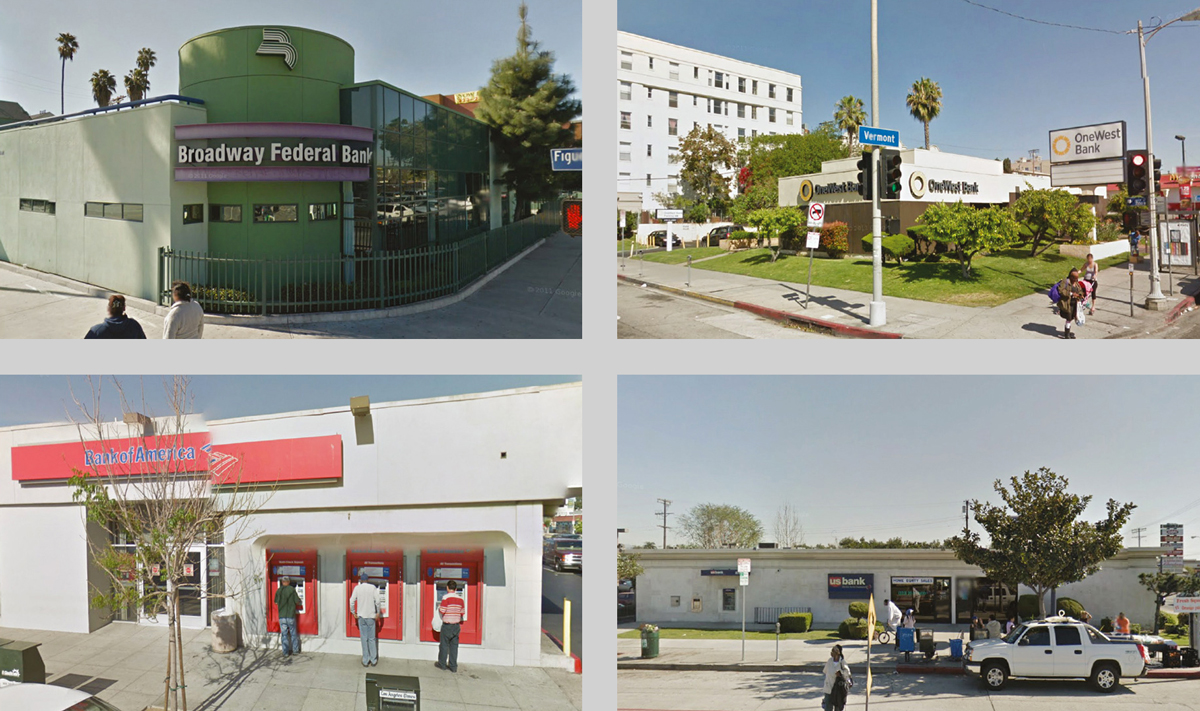

In his 2003 memoir Where The Money Is: True Tales from the Bank Robbery Capital of the World, co-authored with Gordon Dillow, retired Special Agent William J. Rehder briefly suggests that the design of a city itself leads to and even instigates certain crimes—in Los Angeles’s case, bank robberies. Rehder points out that this sprawling metropolis of freeways and its innumerable nondescript banks is, in a sense, a bank robber’s paradise. Crime, we could say, is just another way to use the city.

Tad Friend, writing a piece on car chases in Los Angeles for the New Yorker back in 2006, implied that the high-speed chase is, in effect, a proper and even more authentic use of the city’s many freeways than the, by comparison, embarrassingly impotent daily commute—that fleeing, illegally and often at lethal speeds, from the pursuing police while being broadcast live on local television is, well, it’s sort of what the city is for. After all, Friend writes, if you build “nine hundred miles of sinuous highway and twenty-one thousand miles of tangled surface streets” in one city alone, you’re going to find at least a few people who want to really put those streets to use. Indeed, Friend, like Rehder, seems to argue that a city gets the kinds of crime appropriate to its form—or, more actively, it gets the kinds of crime its fabric calls for.

Of course, there are many other factors that contribute to the high incidence of bank robbery in Los Angeles, not least of which is the fact that many banks, Rehder explains in his book, make the financial calculation of money stolen per year vs. annual salary of a full-time security guard—and they come out on the side of letting the money be stolen. The money, in economic terms, is not worth protecting.

Special Agent Cotton plays a minor role in Rehder’s account of bank crimes in Los Angeles, and through her I was able to meet Rehder to discuss his book, which offers an unexpected perspective on contemporary urbanism. Often overlooked or even deliberately dismissed by architects and urban planners, this view of the built environment is how

In literature, of course, the detective is a well-known trope for a method of obsessively close attention to the details of the built environment—the detective story as applied urban hermeneutics—and this can be seen everywhere from Paul Auster and Alain Robbe-Grillet to whatever thriller is currently topping the airport bestseller list. But in the world of architecture and urban planning, it is altogether too rare that this particular, if fictionalized, point of view on how humans take advantage of the built environment as a spatial opportunity for crimes of various types is taken seriously as a critical perspective on urban form.

It is no less true that

On a recent visit to Los Angeles, my wife and I met Rehder for a long lunch at the Santa Monica Airport, at a restaurant he had chosen. Rehder ordered an Arnold Palmer, called the waitress “darling,” and showed us through a small stack of files holding black-and-white photographs, personal notes he’d written to himself in preparation for our meeting, and some newspaper clippings related to major cases he’d worked on. In fact, one thing I’ve come to realize over the course of many meetings with retired

Rehder has stayed busy in his retirement, he explained, and now runs a consulting firm called the Security Management Resource Group, “a professional firm providing effective and cost-efficient prevention solutions to robbery, violence, and other crimes at financial institutions, stores, and other corporate facilities.” His partner is a former head of security at Bank of America. Rehder’s expertise in all things bank-crime-related also led to the surreal accolade of having been tapped to serve as an outside consultant on the 1991 film Point Break, a thriller starring Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze and directed by a young Kathryn Bigelow, although he tends to laugh when telling that particular story. Rehder’s colleagues apparently ribbed him about the movie for years afterward.

One particular story from Rehder’s book came up again and again as we talked: the story of the still-unsolved crimes of the so-called Hole in the Ground Gang from Los Angeles in the late 1980s. Rehder admitted that he had hoped his book would inspire the perpetrators (he prefers the word “bandits”) to come out and publicly identify themselves, as their crime is now well beyond the statute of limitations. As he put it, these particular bandits could strut into

In June 1986, employees at a First Interstate Bank in Hollywood, at the corner of Sunset and Spaulding in a building that now houses a talent agency, began to report strange mechanical sounds coming from the ground near the vault. However, neither police nor the bank’s security team could find any evidence of wrongdoing or attempted entry—and none of the vault’s own internal sensors had been tripped. Later, when Rehder conducted interviews with bank employees as part of his investigation, he learned that the police had simply dismissed the sounds as “just a rat running around inside the walls or something,” and so nothing was done. Another week went by and the noises continued. The power occasionally went out, as did the phones. Then the bank’s internal Muzak system abruptly kicked in late one evening, startling a manager. Bank employees started “joking about the ‘poltergeist’ that [had] taken up residence at the First Interstate,” Rehder writes, as the security company still found no breach of the vault itself and, incredibly, a supernatural haunting of the bank’s electrical system appeared more likely than someone tunneling up from below.

The sounds were not, however, caused by ghosts but by a group of three or four men at least to some degree professionally trained, the

Rehder opened a file titled “Tunnel Job.” Inside were a handful of glossy color photographs that seemed to have been taken quickly, under less than ideal lighting conditions, and sometimes not even in focus. They showed bewildered

The photographs also revealed how impressive the scale of the tunnel really was. With its tight corridors chipped through the sandy ground of subterranean

The story of the break-in is itself astonishing, but then something even more extraordinary happened. The burglars not only succeeded; they utterly disappeared—until, that is, more than a year later, when they struck again. This time, it was at the intersection of La Cienega and Pico, where they were attempting to burglarize two banks simultaneously. But this time, things did not go so smoothly. The group actually did make it into one of the vaults—but without the preliminary false alarms and the reported poltergeists of the First Interstate in Hollywood, their tripping of the alarm was taken seriously and they were interrupted right before they could make off with their haul. They escaped—narrowly—and remain uncaught to this day.

The stakes of this second robbery were huge; Rehder writes that “they could have gotten away with a face-value take of anywhere from $10 to $25 million. It could have been the biggest bank burglary in the history of the world.” What strikes me as particularly memorable about this latter attempt at burglary—in addition to the sheer hubris of tunneling simultaneously into two banks and even more than the possible monetary take—is the disoriented, almost psychedelic, reaction of Rehder, one of the first

The

This is perhaps the most extreme, and interesting, example of how ways of interpreting the city borrowed from the world of crime—both from those committing it and those preventing it—belong in the architectural curriculum. The insights offered by slicing through the complex topology of the built environment can be extraordinary, despite the fact that, or perhaps precisely because, acting upon these insights is illegal. They are, we might joke, crimes against space.

Gazing in awe at the surface of Los Angeles and realizing that this surface hides holes, tunnels, routes, knots, and other unlawful passages leading from one location to another brought Rehder to a kind of federal hollow earth theory in adversarial appreciation of what lies below. Policing the city, in that moment, becomes as much about preventing new spatial connections—new and illicit diagonals leading from one point to another—from emerging as it is about watching its surfaces for crimes yet to occur. As Rehder recalled, the investigation quickly descended into a giant game of Whac-A-Mole, with federal agents and local cops popping out of manholes throughout the area as they tried to figure out exactly where they were, lost in the underside of the city, the bandits themselves by then long gone.

Geoff Manaugh is a freelance writer and blogger based in New York who publishes widely on landscape, architecture, and technology. He is the author of The BLDGBLOG Book (Chronicle Books, 2009) and a forthcoming book on the relationship between burglary and the built environment (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014). He is director of Studio-X NYC, an off-campus event space and urban futures think tank run by the architecture department at Columbia University.