Written on the Body

Cheiro, Francis Galton, and the reading of hands

Susan Zieger

An Irish lad travels to India in the 1880s: not unusual for the mid-nineteenth century, when the Jewel in the Crown of the British Empire was tended and administrated by legions of Scottish, Welsh, and Irish men seeking livelihoods and opportunities closed to them at home. But only one such teenager sought the tutelage of a Brahmin in the ancient Vedic art of palmistry. For two years, William John Warner learned the practice, inflected by astrology, of reading character and destiny in the seven principal shapes of hands, and the palm’s major and minor lines and their intersections. When he moved to London, he styled himself “Cheiro”—after cheiromancy, or divination by palm reading—and read the palms of celebrities such as Sarah Bernhardt, Oscar Wilde, Mark Twain, William Gladstone, and others. He also launched a publishing juggernaut, some of whose titles remain in print to this day. Cheiro’s Language of the Hand (1894), Cheiro’s Memoirs: The Reminiscences of a Society Palmist (1912), and You and Your Hand (1932) all made cheiromancy a popular pastime, easily accessible and appealing to a modern reading public curious about ancient Eastern wisdom. Cheiro traveled the world, and in his golden years, landed in Hollywood, where he read the palms of aspiring actors and wrote screenplays. He predicted his death, in 1936, down to the hour. Though forgotten, Cheiro was a colorful fin de siècle character who made palm reading, with its Orientalized mystery and distinctive visual aesthetic, a mass cultural practice. The craze was part of a new, broader visual culture featuring the hand, which modern reprographic techniques made into an object everyone could decipher.

Indian cheiromancy and astrology came to Europe when Indologists such as Max Müller and Paul Deussen translated the Upanishads and other Vedic works into German and English. The key text was Hasta Samudrika Shastra (literally, “Hand Body Knowledge”) from ca. 3000 BC, which interpreted over 150 common lines on each hand as indicators of one’s personality and future. Adapting this knowledge to modern times, Cheiro’s manual Language of the Hand opens with “cheirognomy,” or the interpretation of the seven hand shapes: the elementary, the hand’s lowest form; the square, “useful” hand; the spatulate or “nervous active type”; the knotty “philosophic” hand; the conic or “artistic” hand; the mixed hand (a combination of multiple types); and highest of all, the psychic or idealistic hand.[1] As Cheiro renders them, hand types operate by racial hierarchy: for example, the lowest hand form, the elementary, is found in so-called primitive races, while the square hand of Europeans denotes the love of reason and respect for authority. One might expect Europeans to possess the highest order of hands, but Cheiro defies expectations of racist ordering, making esoteric knowledge aspirational for European readers. Everyone’s hand lines indicate their unique character and future, but some are more unique, and others are more typical of their race or ethnicity. The illustrations in Cheiro’s books become more technical when he moves on to the major and minor lines of the palm. There are seven major lines: Life, Head, Heart, the Girdle of Venus, Health, Sun, and Fate. He illustrates these lines, as well as other “signs” made from their intersection, abstractly, without depicting the palms. These resemble nothing so much as a primer for an enigmatic pictorial language. The deciphering of one’s intimate body parts through esoteric knowledge appealed widely, its folk wisdom feeding a modern fad.

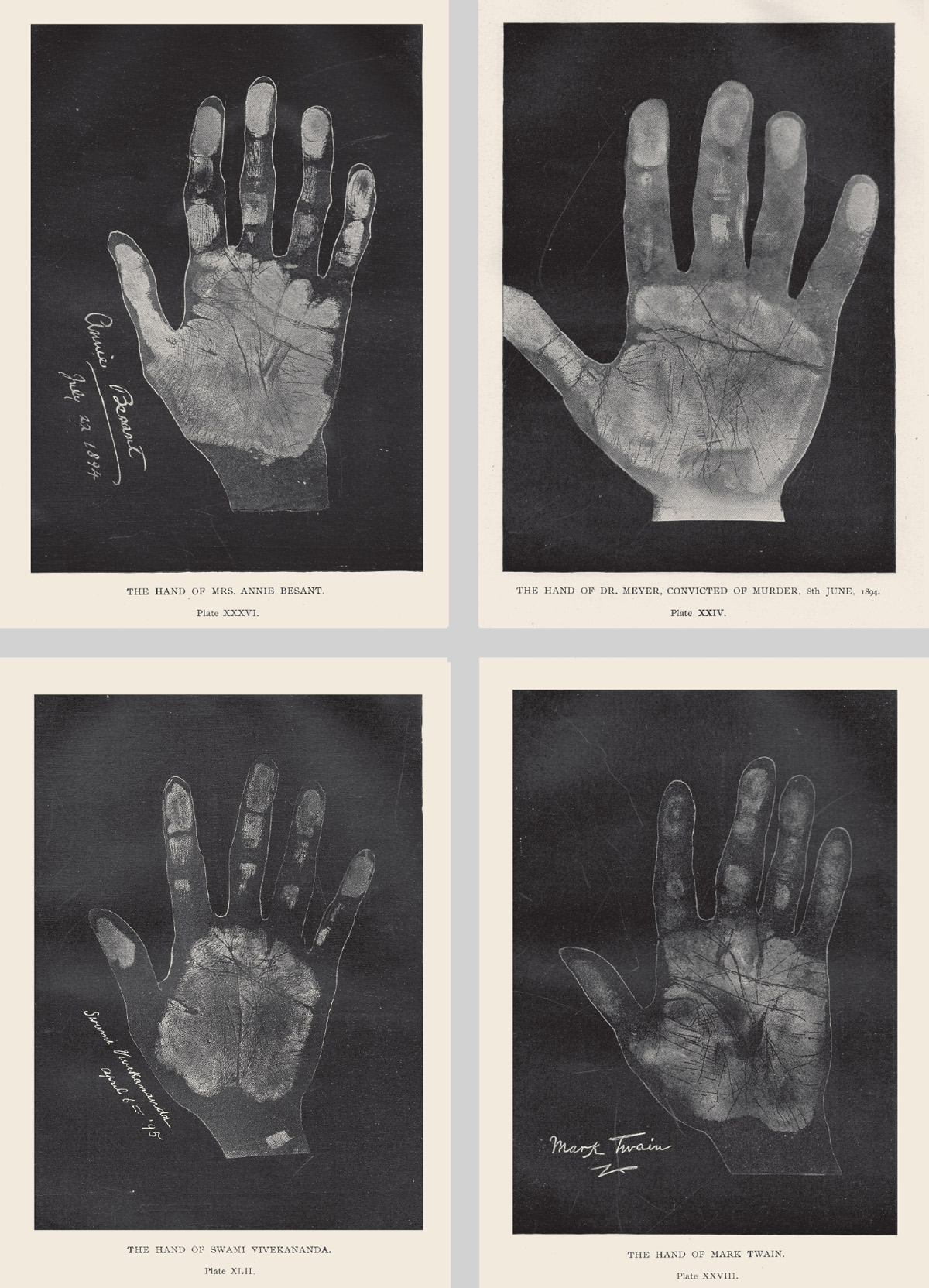

This modernity can be seen in the most arresting images in Cheiro’s books: luminous photographs of celebrities’ hands. Petra Löffler claims that photography made the hand “a special pictorial object” in the nineteenth century.[2] Cheiro’s photographs are fine-screen halftones, with the outline of the hand and some other details drawn in. An ink impression was made of the hand, then reversed to make the lines clearer. The subject’s signature has been added through line engraving.[3] As indexes of the celebrity body, the hand and its signature double each other, inviting interpretation and seeming to disclose intimate personal secrets. Through these photographic and reproductive techniques, light washes the surface of the palm and makes its lines legible. Such images conceptually invert the X-ray developed by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895. The X-ray enacted Michel Foucault’s concept of the clinical medical gaze, which penetrates the body’s surface to make its interiors visible. By contrast, Cheiro’s luminous hands reveal the details hidden in plain sight of the surface. The thrill of palm reading lay not in opening up and visually entering an opaque body, but in the flash of illumination that made tiny lines visible to the eye, and available for translation.

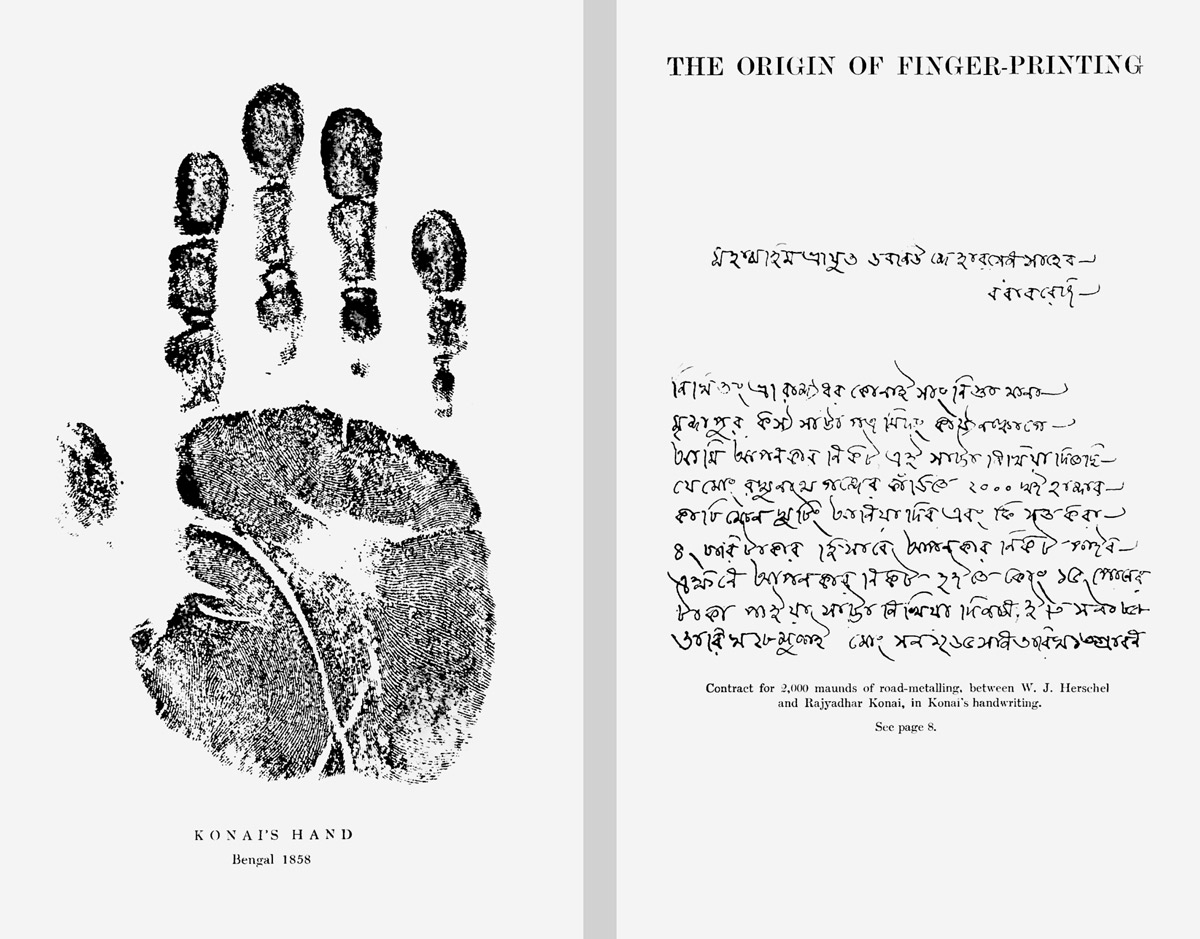

The play of visual power over the hand’s surfaces grew from both an Orientalist desire for eastern knowledge, in Cheiro’s works, and the racial anxieties that attended British imperial governance. In the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, William Herschel, grandson of the astronomer of the same name, had experimented with handprints and fingerprints as a method of enforcing contracts and identifying pensioners. Herschel confessed that the famous “Konai contract,” the first modern use of a digital print for identification, was more an effort to intimidate Rajyadhar Konai into complying with the contract than to furnish useful visual information, since the fingertips are too blurry to interpret.[4] In the 1890s, Francis Galton developed Herschel’s idea, and the London Metropolitan Police began using his system as a method for identifying criminals. Galton was frank about fingerprints’ instrumentality to a racist colonial vision: in India, he writes in his 1892 book on the subject, where “the natives … are characterized by a strange amount of litigiousness, wiliness, and unveracity,” British administrators needed a method for differentiating them, since they all looked alike.[5] In Britain, where the populace is not automatically suspected and more easily visually distinguished, fingerprints could be used to solve crimes and identify bodies. As a visual technique for stabilizing identity, fingerprints performed a Victorian dream of cataloguing and controlling the populace. The affair of the Tichborne Claimant, Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894), and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories all attested to the new forensic visualization and materialization of race, as informed by colonial institutions.[6]

Though Galton was a respected scientist, who developed statistics, eugenics, and composite photography, and Cheiro was an entertainer and media phenomenon, their creation of manual and digital aesthetics shared broad similarities. Scrutinizing handprints so clearly resembled reading fingerprints that Cheiro, feeling an ambivalent rivalry with Galton, boasted of helping to solve a murder investigation that hinged on “a blood-stained hand mark on the paint of a door ….”[7] Both engaged in prediction, Cheiro by divination, Galton by mathematics. Having determined that an individual’s fingerprints remain unchanged over their lifetime, Galton calculated that the chances of two people having identical fingerprints was 1 in 64 billion.[8] Each predicted the future by using new visual and reprographic techniques to enlarge tiny lines on the hand.

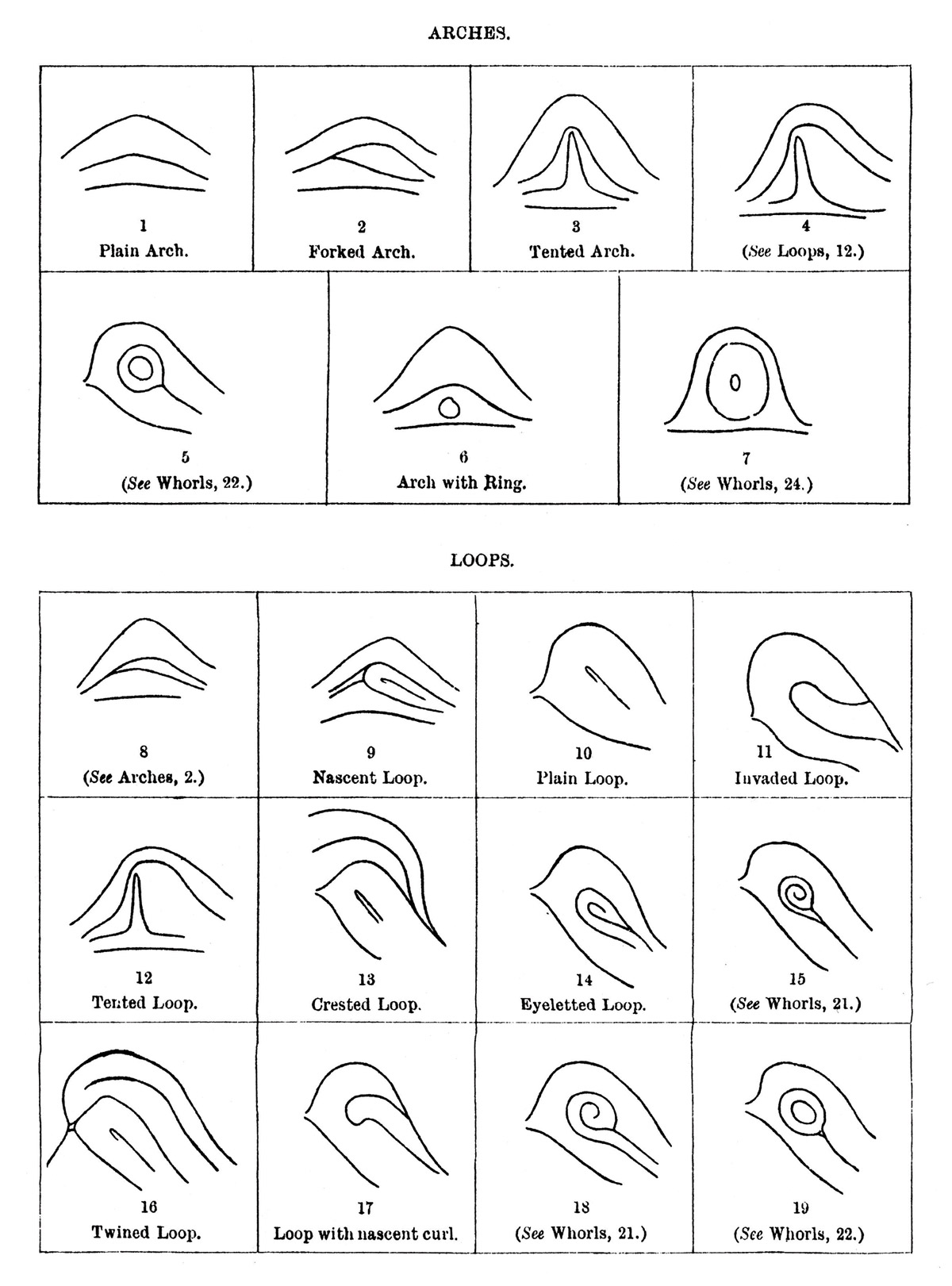

The minute topography of the fingertip becomes visible in the line drawings, enlarged photographs, and diagrams in Galton’s book. He describes his efforts to view fingerprints using a linen tester, a magnifier with a scale typically used to count threads; as well as an enlarging pantograph “in which the cross-wires of a lower-power microscope took the place of the pointer.”[9] He describes the way outlining allowed fingerprint knowledge to emerge from the visual confusion of the enlarged print. “What seemed before to be a vague and bewildering maze of lineations over which the glance wandered distractedly, seeking in vain for a point on which to fix itself, now suddenly assumes the shape of a sharply-defined figure.”[10] Galton narrates the gradual process of enlarging the minute image, then visually summarizing it, and then converting this visual information into mathematical information. Enlarged photographs can include 157 pairs of points of reference, “all bearing distinctive numerals to facilitate comparison and to prove their unchangeableness.”[11] These points become the material for Galton’s probabilistic calculations. In this way, enhanced visual perception creates mathematical knowledge and the certainty of identification—or so it seems.

Putting Galton’s process into dialogue with Cheiro’s reveals that the former is in fact also engaged in a less objective mode of reading than it claims for itself. Is Galton’s more scientifically grounded practice really so different from Cheiro’s westernized Vedic wisdom? The Oxford English Dictionary dates to 1860 the first usage of “reading” as divination through the scrutiny of objects such as tea leaves, palms, or cards. When those trained in reading fingerprints identify the points of reference Galton lists, they too perform an interpretive process. This point formed the basis of the controversial 2002 legal finding of Judge Louis Pollack in The United States v. Llera-Plaza that fingerprint determinations were not testable, and could not be verified absolutely. Since they did not meet the criteria of scientific testimony, Pollack contended, all fingerprint evidence in US criminal cases should be thrown out. As Peter Brooks retells the story in Enigmas of Identity, Pollack later retracted the decision, demonstrating that “our criminal justice system, and our culture more generally, are not yet ready to do without fingerprints.”[12] The scientific myth of fingerprints holds firm, yet when we compare Cheiro’s and Galton’s outlining and summary of hand lines, the differences between divination and mathematics dissolve in an emergent late nineteenth-century practice of reading. This activity is not merely the consumption of print, but the production of predictive, contingent information through visual interpretation. Redefining fingerprint analysis as reading or interpretation allows us in turn to accentuate fingerprints and handprints as aesthetic rather than stable, scientific objects.

In addition to criminal justice systems, in the twentieth century the fingerprint came to feature in border and immigration controls worldwide. As a biometric marker, the fingerprint constrains mobility and travel, whether through ink and paper or more recent infrared and ultrasonic technologies. Seeing finger- and handprints as interpretive objects, cultural producers contest the reduction of personhood to identity, pushing back against neoliberal and fascist uses of identificatory technologies developed from Galton’s visual knowledge production. In 2011, for example, the photographer Gary Schneider made the “HandPrint” series featuring palm prints of South African artists enlarged to monumental scale. With their milky, otherworldly look, these images resemble Cheiro’s, whose visual legacy they extend. Its Orientalizing tendencies notwithstanding, Cheiro’s palmistry suggestively evokes a person’s unique plenitude. Schneider’s palms develop this impulse: rather than just identifying the artists, the palms conjure their individual depth. They document the artistic community in Johannesburg, archiving the unique signatures of the craftspeople, painters, and photographers who work there.[13] And at the Venice Biennale of 2017, the Tunisian Pavilion staged “The Absence of Paths,” which employed fingerprints parodically to expose the political and financial power invested in their ordinary usage. At one of three checkpoints, visitors were issued passports from no nation. The interactive installation, ascribed to no single artist, reimagined the ongoing global immigration crisis by issuing passports that featured the holder’s thumbprint and the words, “Status: Migrant” and “Only Human.” The kiosk where I obtained mine was sited at an outdoor checkpoint formerly used by the Italian navy to control the shipyard at Arsenale.[14]

These artistic interventions notwithstanding, identificatory technologies are only growing more important in the expansion of neoliberal power. Nowhere is their potential for violations of democracy more vivid than the Indian government’s recent launch of the world’s largest database of fingerprints, the Aadhaar (Hindi for “foundation”).[15] Over one billion Indians have provided fingerprints, iris scans, and personal information, and received in return a twelve-digit number identifying them; the intention is to facilitate the government distribution of $40 billion in benefits each year. Aadhaar thus fully realizes Herschel’s Victorian dream of identifying Indians to prevent fraudulent claims on pensions. It is a notable example of present-day biometrics’ fulfillment of nineteenth-century anthropometric systems used to administrate empires.[16] In addition, because the technology is open access, permitting third party use through cell phone apps, its potential for banking and other business development is virtually unlimited. On the one hand, the database brings impoverished Indians into the formal economy, giving them an identity and access to credit; on the other, it makes their unique information available to businesses and to the government, enabling coercion, control, and errors. These include damaging leaks of personal information, and—ironically—the withholding of legitimate benefits through ordinary technical mishaps.[17] It is instructive to compare this fingerprint-focused vision of life as primarily financial—a unique string of numbers, a credit line, government benefits—with palmistry’s vision of character and destiny, drawn from Hasta Samudrika Shastra. One is reductive and banal; the other, poetic and mystical. Yet both make sense of an individual human life through tiny prints of hands and fingers. When Schneider and the Tunisian Pavilion engage Cheiro’s handprints and Galton’s fingerprints, they ask us to read down through the lines of history each of us bears.

- Cheiro, Cheiro’s Language of the Hand (New York: published by the author, 1894), p. 26.

- Petra Löffler, “What Hands Can Tell Us: From the ‘Speaking’ to the ‘Expressive’ Hand,” in Media, Culture, and Mediality: New Insights into the Current State of Research, ed. Ludwig Jäger, Erika Linz, and Irmela Schneider (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2010), p. 373.

- Gerry Beegan, email to the author, 8 May 2017.

- Andre A. Moessens, Fingerprint Techniques (New York: Chilton, 1971), p. 10.

- Francis Galton, Finger Prints (London: Macmillan and Co., 1892), p. 149. Further citations are to this edition.

- See Aviva Briefel, The Racial Hand in the Victorian Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015) and Sarah E. Chinn, Technology and the Logic of American Racism: A Cultural History of the Body as Evidence (London: Continuum, 2000).

- Cheiro, The Reminiscences of a Society Palmist (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1912), p. 17.

- Francis Galton, Finger Prints, p. 110.

- Ibid., p. 52.

- Ibid., p. 69.

- Ibid., p. 10.

- Peter Brooks, Enigmas of Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), p. 13.

- Maxwell Heller, “What a (Self) Portrait Can Do: Picturing South Africa in New York,” The Brooklyn Rail (December 2011–January 2012). Available at http://brooklynrail.org/2011/12/artseen/what-a-self-portrait-can-do-picturing-south-africa-in-new-york.

- Gareth Harris, “Tunisian Pavilion to Issue Travel Documents at Venice Biennale” The Art Newspaper (5 April 2017). Available at http://theartnewspaper.com/news/tunisian-pavilion-to-issue-travel-documents-at-venice-biennale.

- “Indian Business Prepares to Tap into Aadhaar, a State-Owned Fingerprint-Identification System,” The Economist (24 December 2016). Available at http://economist.com/news/business/21712160-nearly-all-indias-13bn-citizens-are-now-enrolled-indian-business-prepares-tap.

- See Joseph Pugliese, Biometrics: Bodies, Technologies, Biopolitics (New York: Routledge, 2010), pp. 42–55.

- “The World’s Largest Biometric Database Is Leaking Indian Citizens’ Data—But Keeps on Growing,” Global Voices (2 May 2017). Available at http://globalvoices.org/2017/05/02/the-worlds-largest-biometric-database-is-leaking-indian-citizens-data-but-keeps-on-growing.

Susan Zieger is an associate professor of English at the University of California, Riverside, and is presently working on a cultural theory of logistics.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.