Sycorax’s Other Son

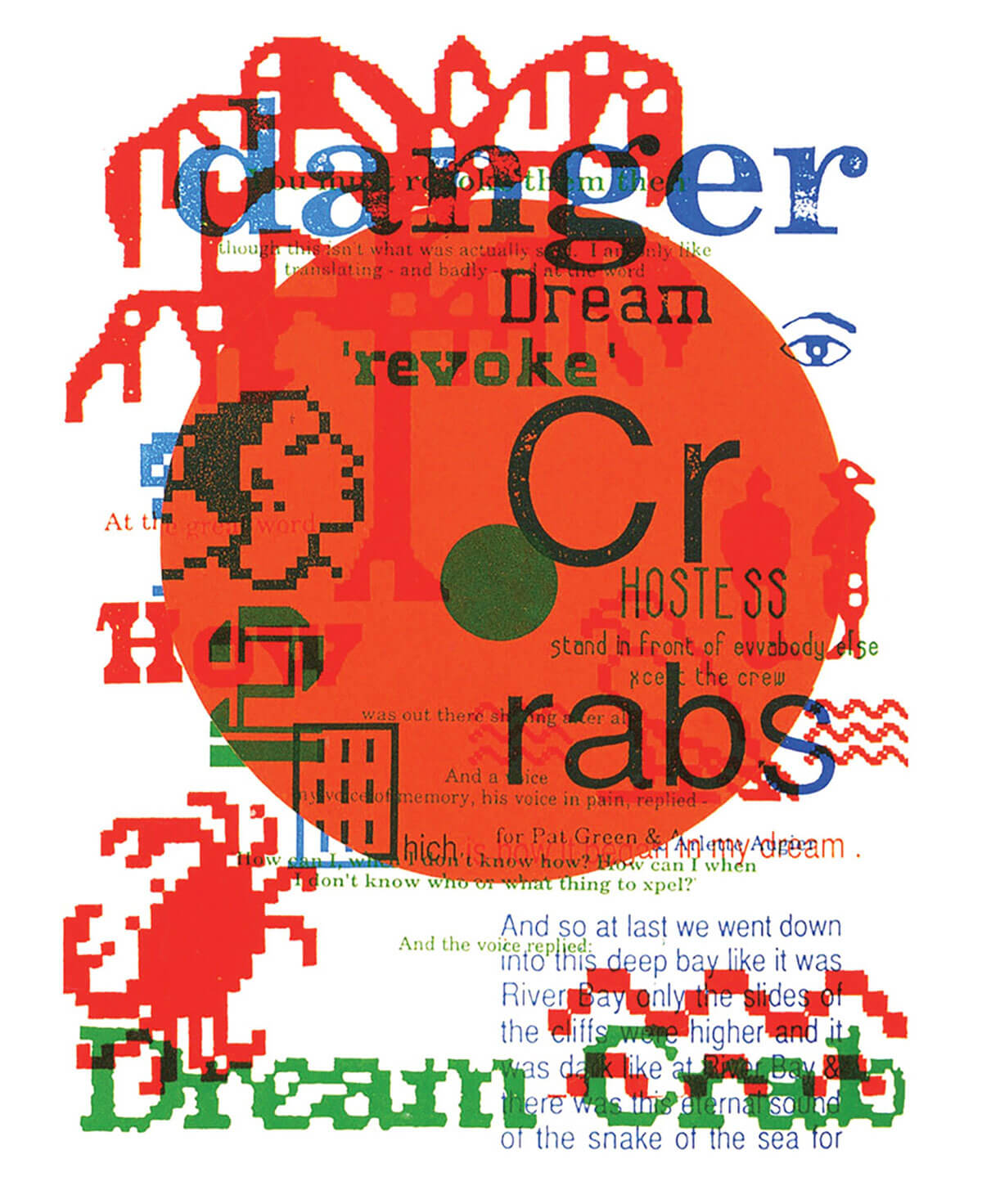

The oneiric origins of Kamau Brathwaite’s “video style”

Yanie Fécu

I come to Sycorax during my Time of Salt: death of Zea Mexican 1986, loss of Irish Town Library of Alexandria 1988, murder by Kingston gunmen 1990… just look at the dread frequencies of these catastrophes. My writing hand becomes a dumb stump in my head… I mean I can’t write or utter a sound or metaphor. But Sycorax comes to me in a dream and she dreams me a Macintosh computer with its winking io hiding in its margins which, as you know, are not really margins, but electronic accesses to Random Memory and the Cosmos and the lwa.

And she dreams me these stories … and shows me how to find jo to write them out on the computer. And the two together introduce me to fonts and the fonts take me across Mexico to Siqueiros and the Aztec murals and all the way back to ancient Nilotic Egypt to hieroglyphics—allowing me to write in light and to make sound visible as if I am in video.

She abolishes, as I say, the traditional margin and the boundaries of books...[1]

Sycorax brought Brathwaite to what he calls his “video style”; what brought Brathwaite to Sycorax? What he refers to as his “Time of Salt” is a cluster of tragedies. Just as sugar looms large in the Caribbean imaginary, so, too, does salt. In one folktale (and its endless variations), consuming too much salt makes enslaved Africans too heavy to fly home. The common expression “to suck salt” means to bear hardship and scarcity. To kill a soucouyant—a blood-sucking witch who sheds its skin at night—the victim must find and salt the creature’s moulted skin. Brathwaite renders his private experiences of pain as world events. In 1986, he lost his wife Doris “Zea Mexican” Brathwaite to cancer. Two years later, Hurricane Gilbert destroyed most of his home, personal library, and extensive archive in Irish Town, Jamaica—the “Library of Alexandria.” And in 1990, three men broke into his house, bound him, and robbed him. During the raid, one of the robbers put a gun to the back of his head and pulled the trigger. The gun was either jammed or not loaded; nevertheless, Brathwaite views this moment as an assassination. The near-death experience is a death experience. That he was struck by a “ghost bullet” makes no difference. His last collection is titled The Lazarus Poems (2017).[2]