Glossary of Dream Architecture (Full Version)

Genus for a new circadia

Richard Sommer and Natalie Fizer

What is the material substrate of dreams, and how does it inform the architectural imagination? The following is a glossary that guided the creation of “New Circadia: Adventures in Mental Spelunking,” an experimental space for idling recently conceived and installed by Richard Sommer and Pillow Culture at the University of Toronto. New Circadia was inspired by Dr. Nathaniel Kleitman’s 1938 Mammoth Cave Experiment (the first staging of a scientific laboratory to study human cycles of sleep and wakefulness) and the ancient Greek asklepion (a ritual health complex with a hidden sleep temple, the abaton). At New Circadia, visitors enter a subterranean space through an anteroom, don anatomically shaped spelunking gear, and proceed to a dark, multi-sensory space—a soft utopia—of collective adventure, relaxation, and reverie.

The glossary gathers buildings, landscapes, events, films, stories, drawings, and other projects that can also be understood to constitute a makeshift history of dream design. Its contents are organized under the following headings: Air, Bricolage, Cave, Cloister, Glass, Grotto, Model, Mountain Aerie, Phantasmagoria, Stone, Temple, Test Bed, Vehicle, and Water. The history the glossary imputes is provisional to our own purposes and guides our ideas about how architecture models time to shape a space of dreams through the measuring, marking, and bounding of various human practices. The dream-inducing architecture of New Circadia begins with a search for tempos within the various and overlapping versions of time we inhabit. These include, but are not limited to: geological/deep time, mechanical/industrial time, wasted/idling time, broken/discontinuous time, organic/biological time, and mythical/story time.

Acknowledging architecture’s complicity in an increasingly stressful and zombie-like world, how can we counter the overmechanization of everyday life? Idling, whether by sleeping, dreaming, napping, or meditating, is not lost, unproductive time, but, rather, is vital to our survival and evolution as a species.

We think it may be time to put architecture to sleep.

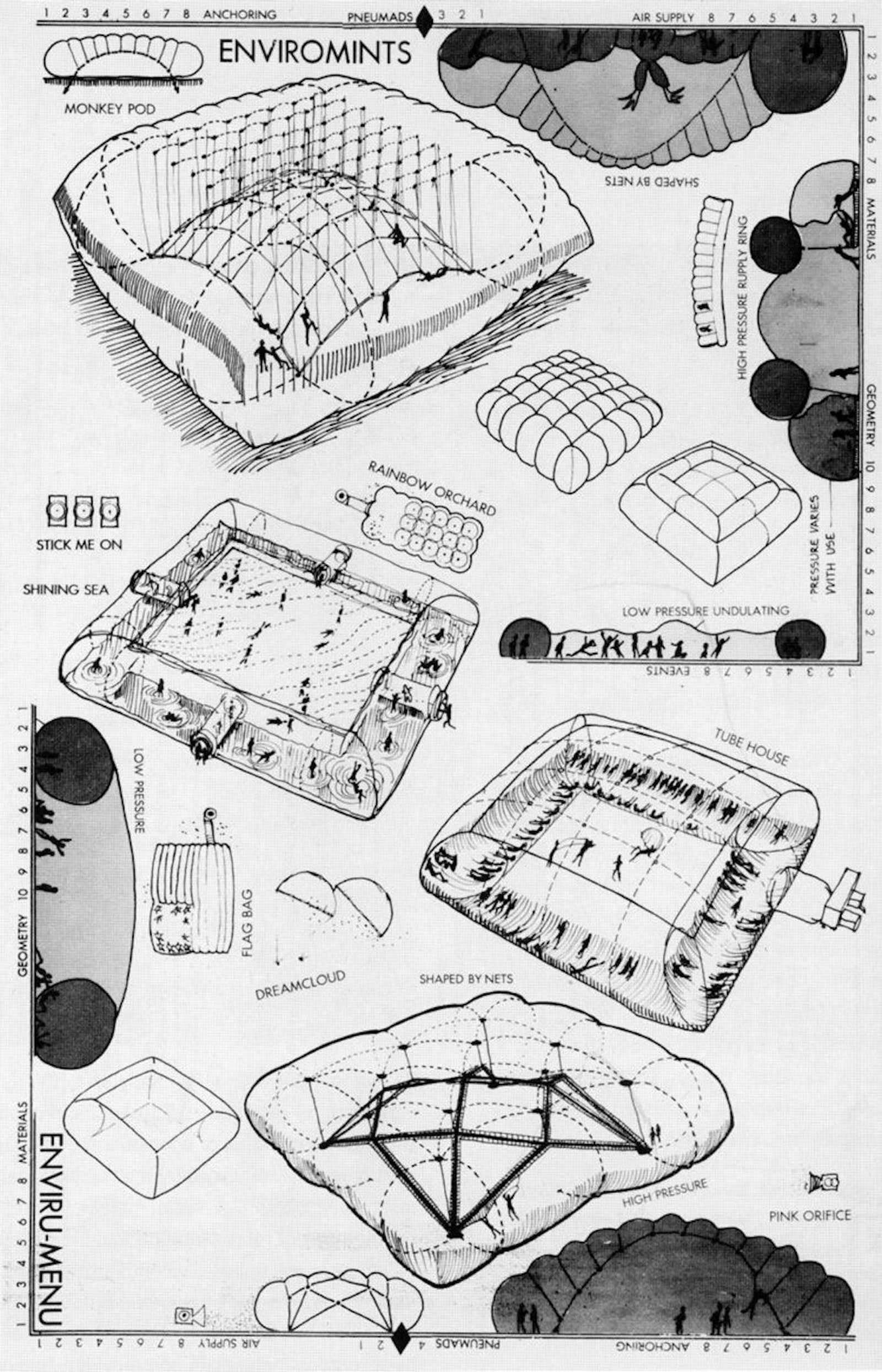

The new-dimensional space becomes more or less whatever people decide it is—a temple, a funhouse, a suffocation torture device, a pleasure dome. A conference, party, wedding, meeting, regular Saturday afternoon becomes a festival.

—Ant Farm, Inflatocookbook, 1971

In its mutability, its playing on gravity and weather, its being there and not there at once, the inflatable is air-architecture incarnate. Ant Farmʼs pneumatic 50' x 50' pillow, first installed in Point Reyes in 1969, was one of a number of large-scale inflatables in various forms that the experimental architecture collaborative proposed and staged starting in the late 1960s. Evoking clouds, Ant Farm’s inflatables were a utopian, countercultural dream of an anti-architecture: do-it-yourself bubbles filled with “free” air and made of cheap polyethylene and tape. Like outer-space capsules, yet tethered to the ground, Ant Farm’s pillows offered a space absent the earth-bound conventions of wall, floor, and ceiling. People could occupy Ant Farm’s air-filled pillows in various states of playful reverie, making them gigantic communal bubbles for collective dreaming. By following Ant Farm’s Inflatocookbook—a graphic manual containing construction templates and instructions on how to calculate air pressure, wind loads, and proper fan sizes—anyone could become an “inflatoexpert.”

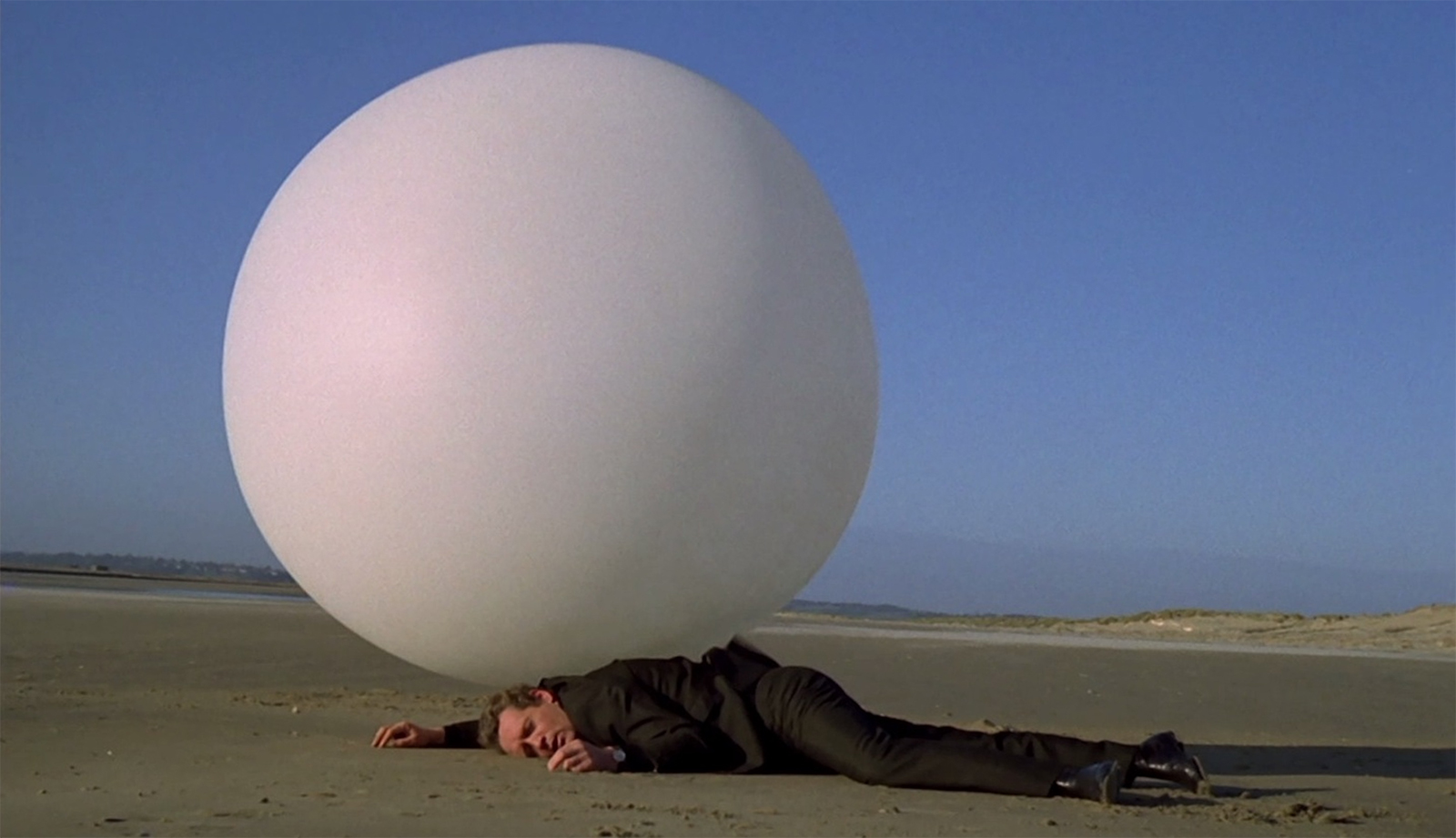

A dystopian counterexample to Ant Farm’s transparent, communal bubble was the Rover, a large, opaque balloon featured in The Prisoner, the British sci-fi thriller TV series broadcast in 1967–1968. All the inhabitants of the “Village,” the show’s Disneyesque prison, were tracked by CCTV. Any resident who tried to escape or oppose the regime would be intercepted by the Rover. Like the Village, the Rover had a happy appearance, but it was in fact a nightmarish orb. Imbued with a murderous, drone-anticipating artificial intelligence, it descended from the heavens to attack and asphyxiate runaways.

The place through which he made his way at leisure, was one of those receptacles for old and curious things which seem to crouch in odd corners of this town, and to hide their musty treasures from the public eye in jealousy and distrust. There were suits of mail standing like ghosts in armour here and there, fantastic carvings brought from monkish cloisters, rusty weapons of various kinds, distorted figures in china and wood and iron and ivory: tapestry and strange furniture that might have been designed in dreams.

—Charles Dickens, The Old Curiosity Shop, 1841

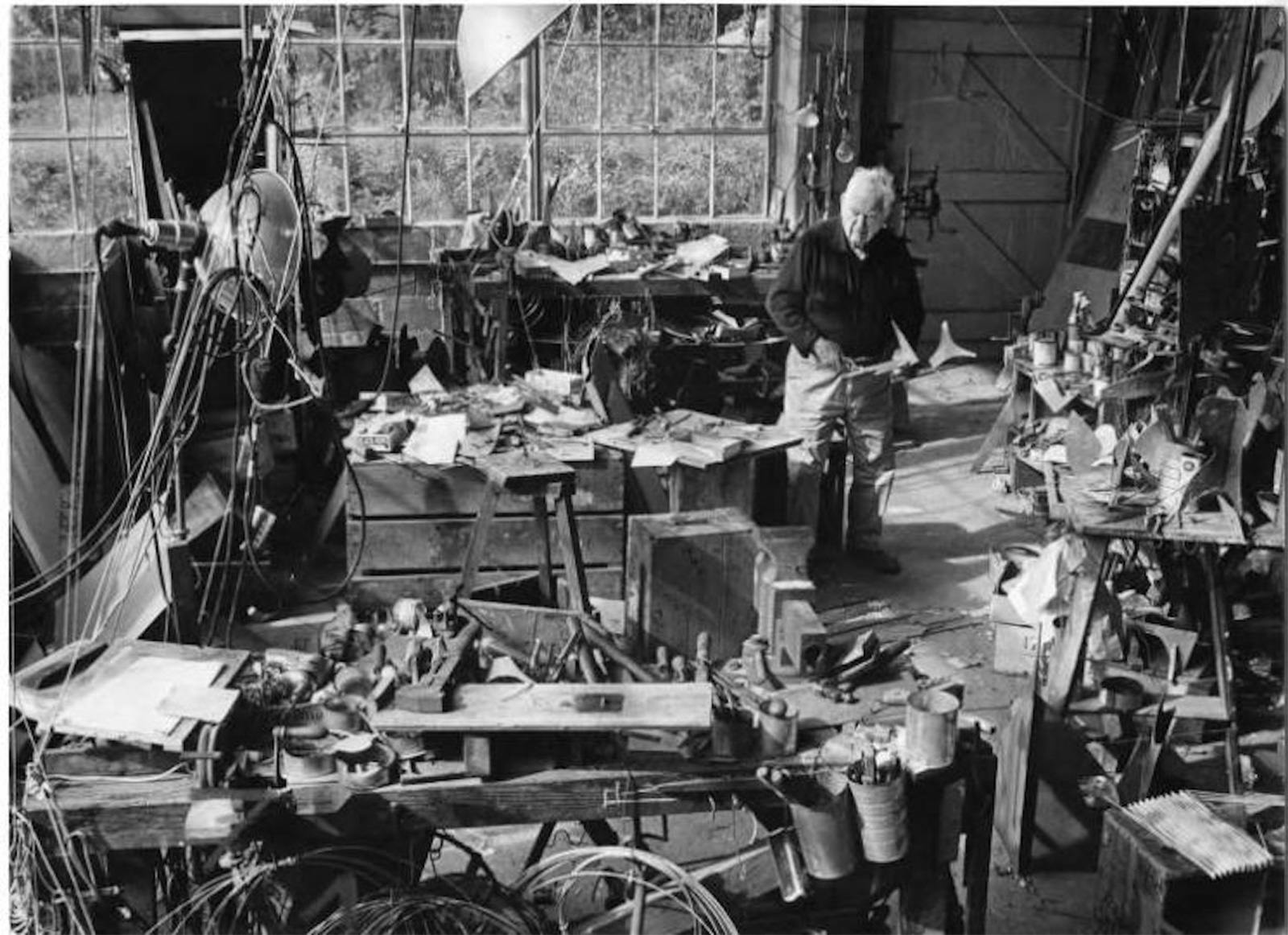

Like the atmosphere of nightmares and horror films, the space of the bricoleur is typically at the margins of domestic or institutional settings: the closet, the attic, the basement, the garage, or the barn. These are sites where the bricoleur collects and stores unrelated objects and materials—discarded things—often found during daily life. In such a space, the bricoleur fiddles or tinkers with an evolving archive of the randomly encountered. The bricoleur juxtaposes unlike things, freeing them from their origins and from coherent meanings. In a nonlinear process of association akin to dreaming, he makes them into uncanny works of art and craft. Since Claude Lévi-Strauss brought anthropological ideas concerning the bricoleur into popular discourse, bricolage has been understood to provide a window onto both Romantic and modern notions of artistic practice. Alexander Calder’s studio and his biographical transformation from engineer to artist-bricoleur exemplify this idea of bricolage as site, space, and sensibility.

Stories of descent into the underworld are so ancient and universal that their fundamental structure, the opposition of surface and depth, may well be rooted in the structure of the human brain.

—Rosalind Williams, Notes on the Underground: An Essay on Technology, Society, and the Imagination, 1990

To descend into a cave is to return to a lithic past, one that evokes narratives of hidden underworlds in many cultures. Affiliated in ancient times with the seat of oracles, magic, and curative powers, the cave is a place of sanctuary, seclusion, and ritual retreat.

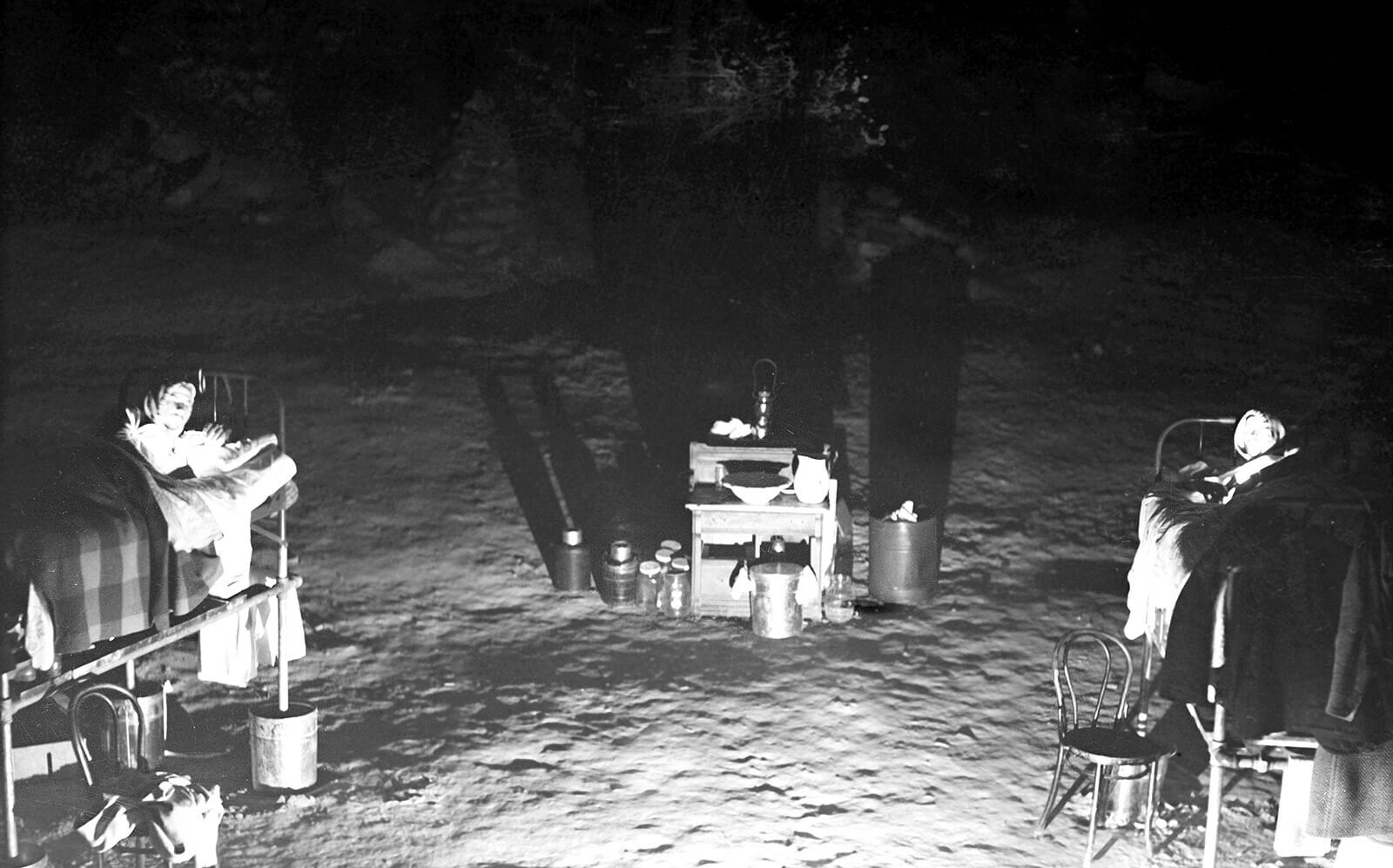

In 1938, Nathaniel Kleitman staged the first scientific research laboratory designed to study the circadian timekeeping of the body in sleep. He set his experiment in Mammoth Cave, Kentucky, one of the longest known cave systems on Earth and an established tourist site. While in many ways an unsuccessful experiment, Kleitman’s use of the cave as a laboratory for conducting a sleep/wake experiment introduced a dramatic narrative aspect through its suggestion that understanding the circadian rhythms of human consciousness requires a retreat into the primordial.

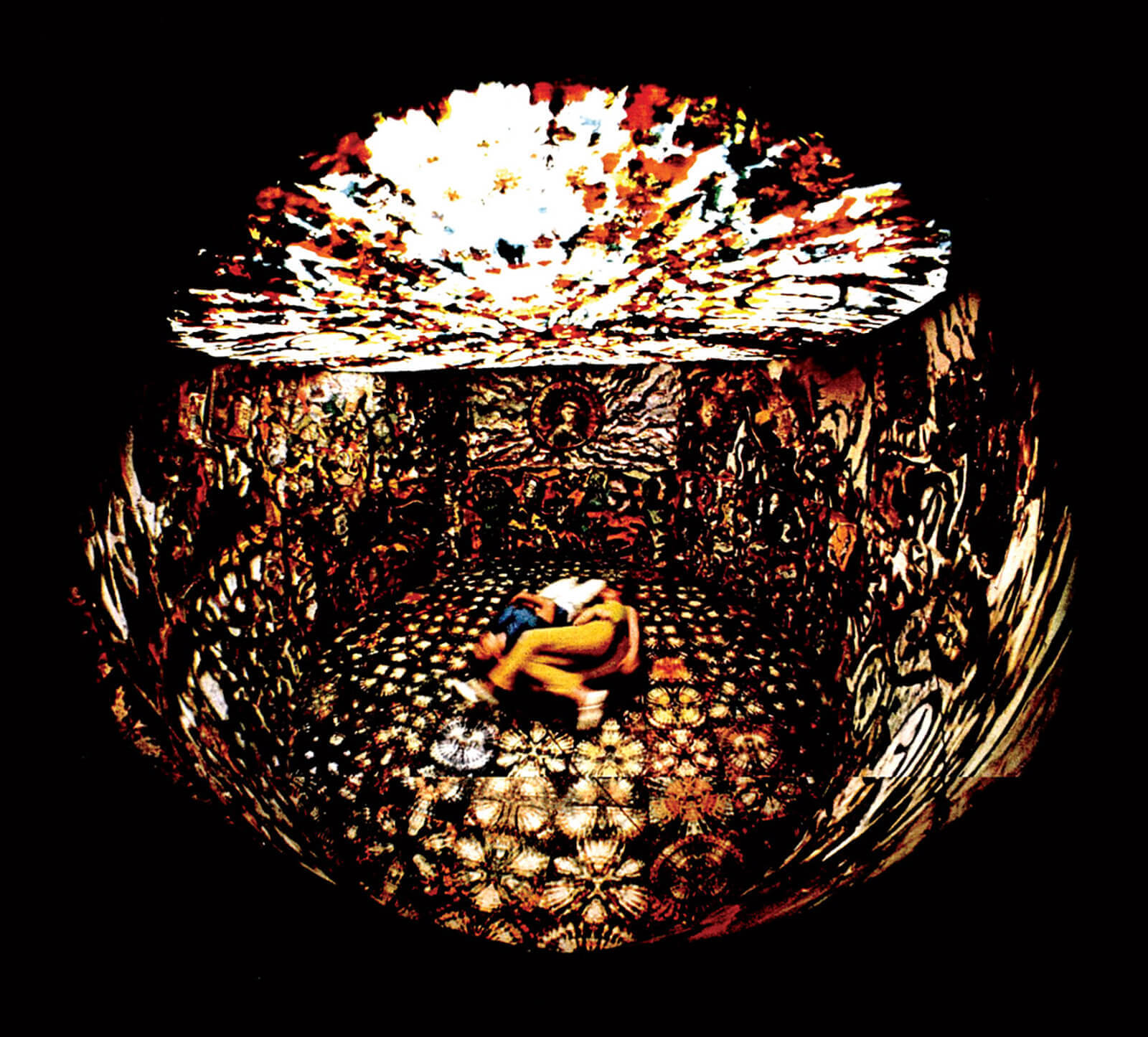

A generation after Kleitman’s attempt, a countercultural search for radical, alternative spaces in which to expand consciousness inspired experiments with psychedelics and other mind-altering drugs, as well as new, sometimes cave-like, synesthetic art spaces. Though roughly contemporaneous with Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests in San Francisco, the 1966 exhibition “Down by the Riverside” by the art collective USCO focused on changing consciousness without the need for chemistry. Among the six enormous, psychedelic, LSD-trip–conjuring rooms constructed at the Riverside Museum in New York City was the “Tie-Dye Cave.” Tie-dye was a revival of ancient techniques of resist-dyeing. USCO’s cave was a hippy concoction that married tie-dye to another trope, the primitive hut, and to the notion—particularly associated with the nineteenth-century German architect Gottfried Semper—that the use of woven tapestry to form enclosures was at the origin of human architecture. The cave was made from a frame clad in mandala-patterned fabrics displaying the visages of humans and deities, with light coming from above. A slowly rotating couch placed at its center invited visitors to sedately experience the room. The Tie-Dye Cave and the other five USCO exhibition spaces are said to have inspired the “Be-In” (sitting chronologically between the earlier “Sit-In” and the later “Sleep-In”), which was soon formalized as January 1967’s “Human Be-In,” held at the Polo Fields in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Organized by individuals loosely associated with USCO’s creative network, the Human Be-In was itself a prelude to the Summer of Love that took place in San Francisco later that year.

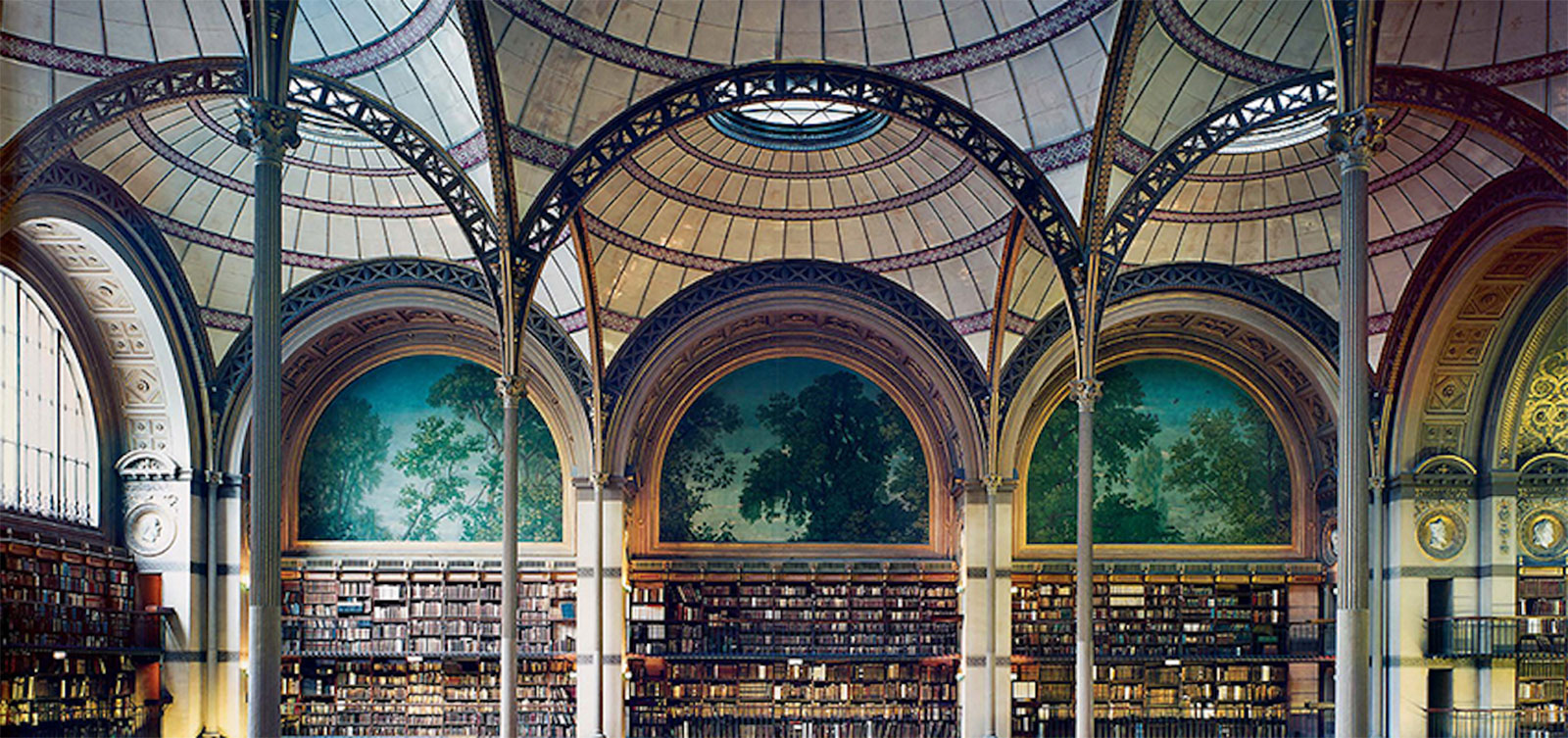

These notes devoted to the Paris arcades were begun under an open sky of cloudless blue that arched above the foliage; and yet—owing to the millions of leaves that were visited by the fresh breeze of diligence, the stertorous breath of the researcher, the storm of youthful zeal, and the idle wind of curiosity—they’ve been covered with the dust of centuries. For the painted sky of summer that looks down from the arcades in the reading room of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris has spread out over them its dreamy, unlit ceiling.

—Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, “Convolute N,” 1934

The cloister, like many forms of architecture, has its origins in an activity that then evolved into a figural space. The cloister, from the Latin claustrum, is a covered walkway or arcade for contemplative perambulation within a monastic church complex. Simultaneously concealing the individual dwellings, or cells, and connecting them to the other, more collective institutional spaces of the monastery, it enables communion, retreat into religious study, and the observance of cyclical rites.

The Christian cloister likely evolved from the secular domestic architecture of antiquity. Eventually, its encapsulated, sacred world-in-miniature helped inspire some of the first secular institutions of the modern era, especially the university with its libraries and museums. The Oxford University Museum of Natural History and the Bibliothèque Nationale are two revolutionary examples from the nineteenth century of the secularized cloister—one intended for display, the other for research. In their rendering of the cloister in new materials and dimensions, they spark individual, worldly epiphanies, rather than religious communion. In both spaces, airy compositions of iron and glass produce an ethereal atmosphere that transcends the arboreal appearance of their columnar structures, borrowed from the vegetal imagery of cloisters. What critics as disparate as John Ruskin and Walter Benjamin found appealing in these spaces was a tension between natural forms, technological progress, and historical memory—a tension that arose in the mid-nineteenth century, and is still the stuff of architectural dreams today.

And the building of the wall of it was of jasper: and the city was pure gold, like unto clear glass. And the foundations of the wall of the city were garnished with all manner of precious stones. The first foundation was jasper; the second, sapphire; the third, a chalcedony; the fourth, an emerald; the fifth, sardonyx; the sixth, sardius; the seventh, chrysolite; the eighth, beryl; the ninth, a topaz; the tenth, a chrysoprasus; the eleventh, a jacinth; the twelfth, an amethyst. And the twelve gates were twelve pearls; every several gate was of one pearl: and the street of the city was pure gold, as it were transparent glass.

—Revelation 21:18–21

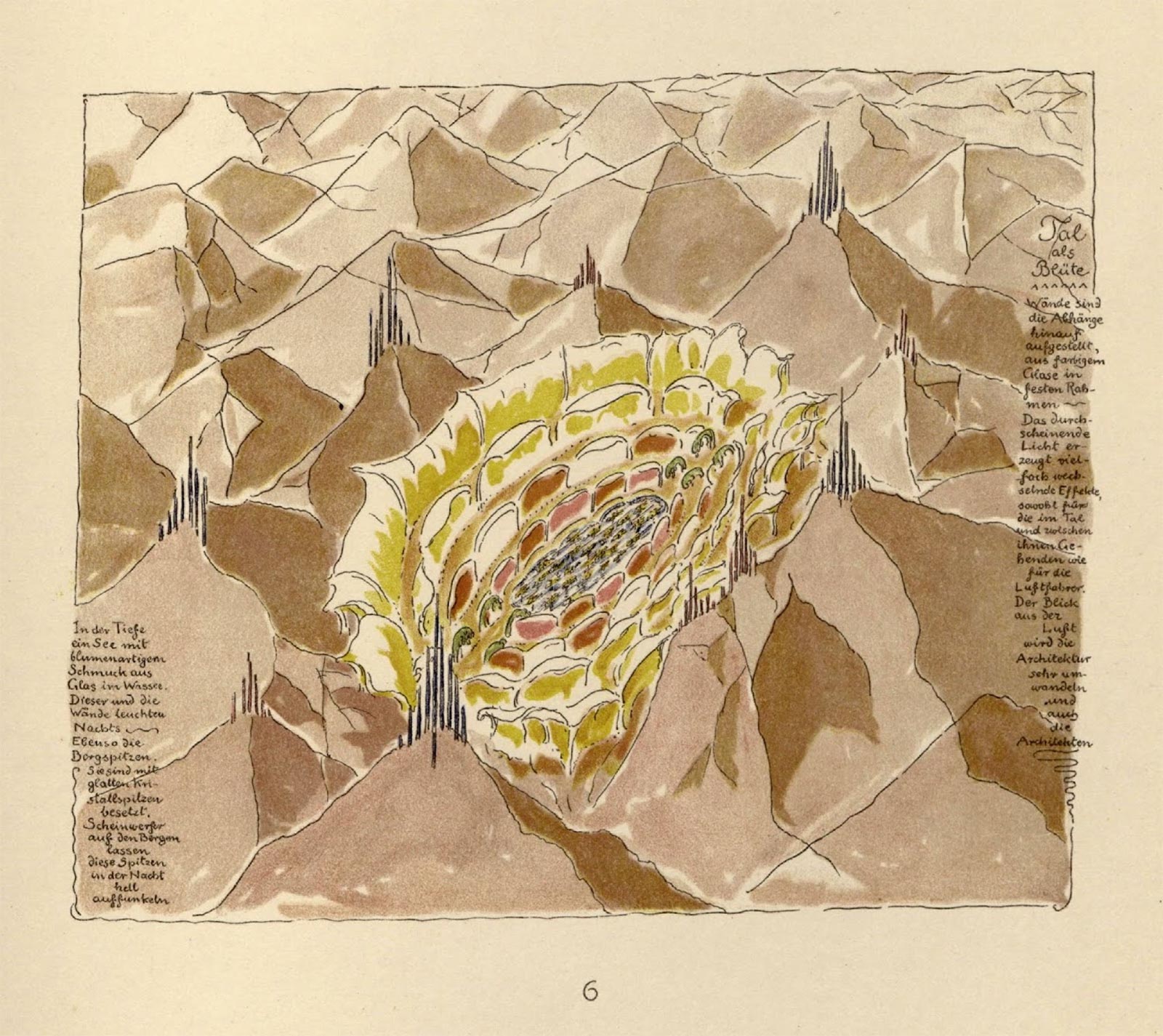

Mythical accounts of a liquid-and-glass architecture date back to early descriptions of Solomon’s Temple, and persisted into the medieval and modern period. Drawing on this history, the early twentieth-century avant-garde promoted glass as an amorphous material possessing crystalline, quasi-geological characteristics. The terms crystal and glass were sometimes uses in scientifically imprecise ways during this period—glass is inorganic and made from the compounding of material, while crystals can have a glass-like appearance but are naturally occurring, and have electrical, conductive capacities. The ambiguous, metaphorical conjunction of the two substances inspired an alchemical architecture of shifting states of translucency and coloration, where the stuff of architecture can transmute from solid to liquid.

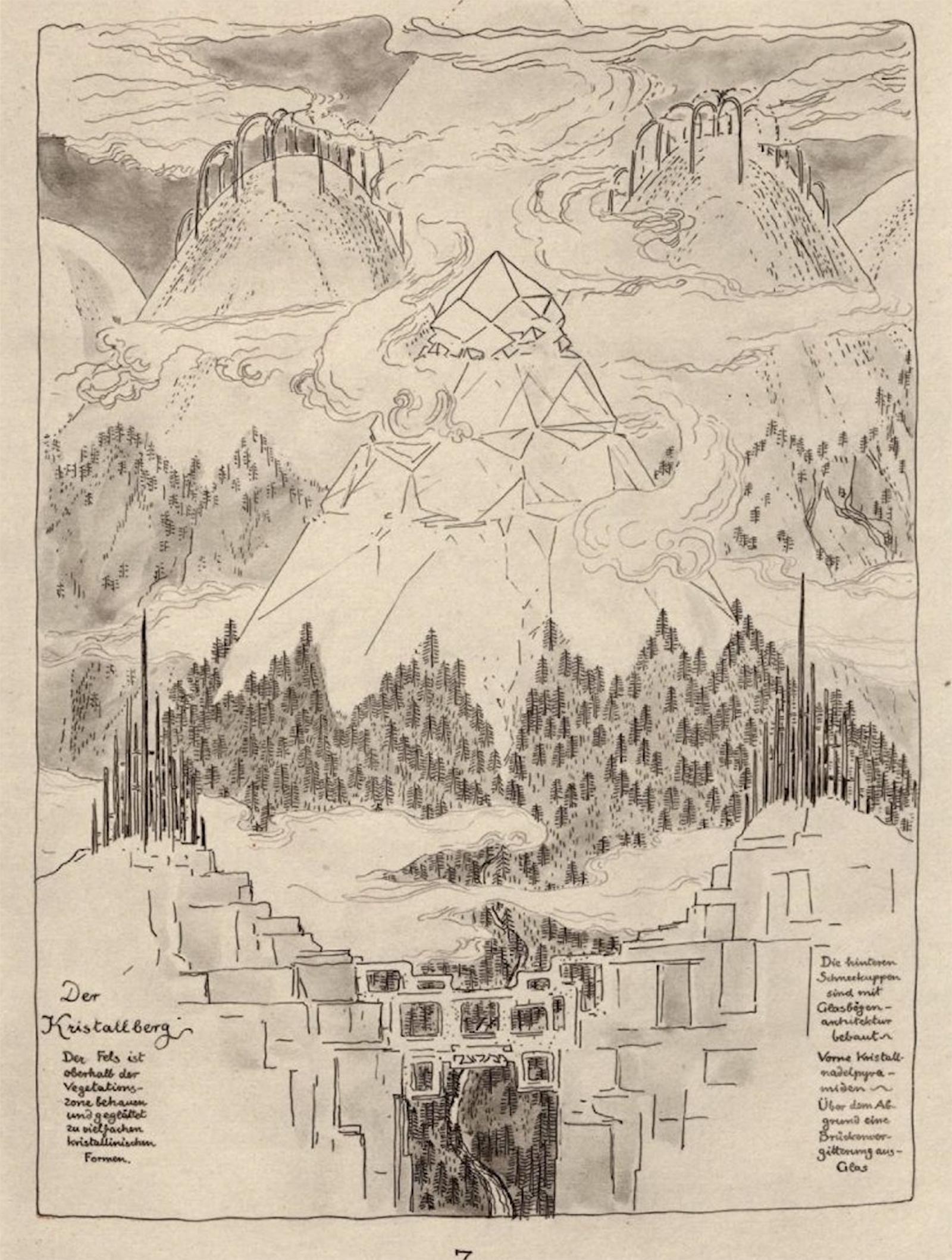

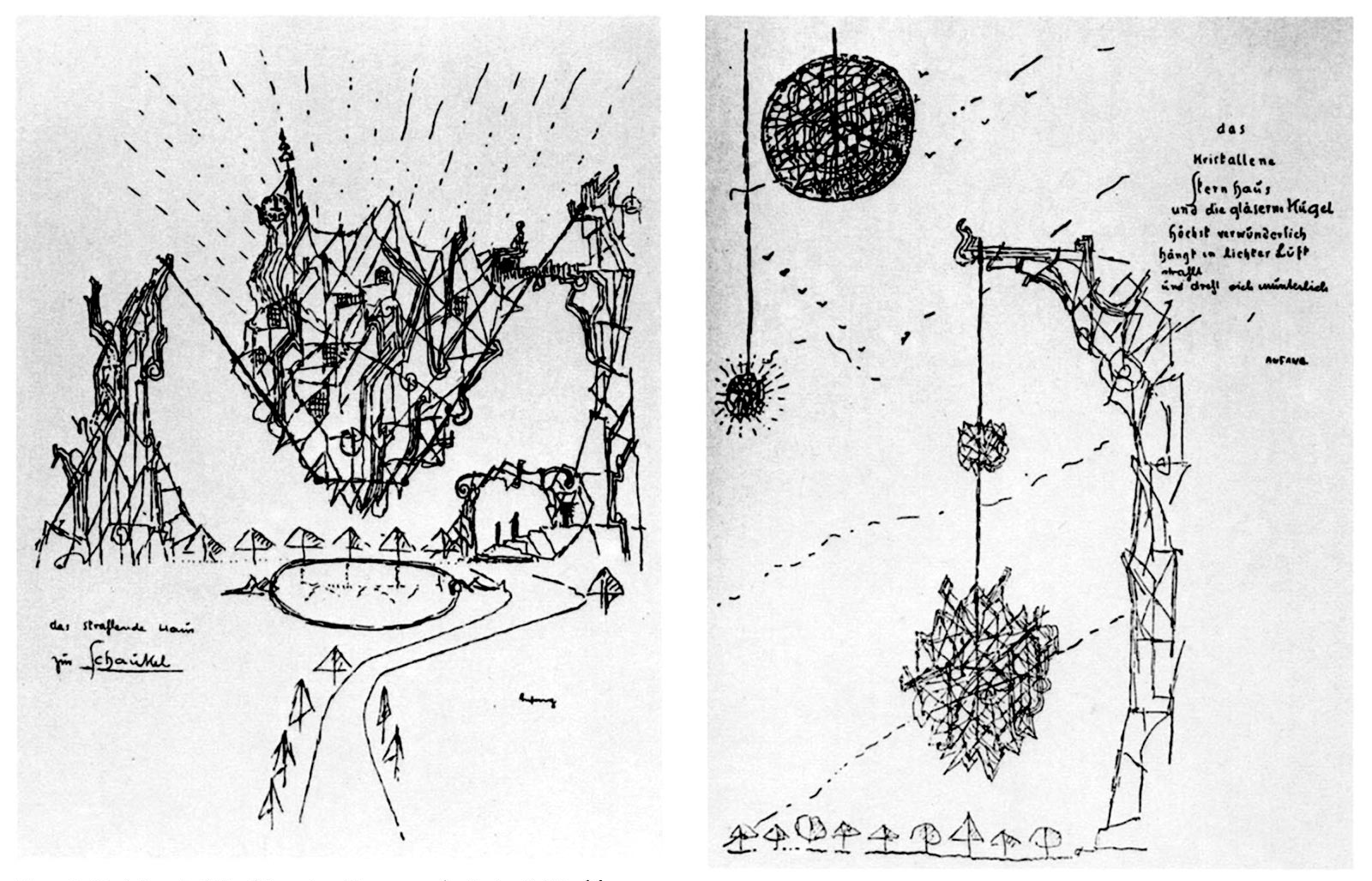

At the end of World War I, the writer Paul Scheerbart’s 1914 text Glass Architecture led the architect Bruno Taut to develop Alpine Architecture, a purely visual treatise of thirty plates based on Taut’s pacifist and socialist beliefs, including his idea that war was the product of boredom. Set in (and seemingly growing out of) the Alps, Alpine Architecture elaborates an otherworldly urban fabric of crystalline architecture antithetical to traditional notions of inhabitation, construction, and material assembly. Soon after, Taut initiated the Glass Chain (or Crystal Chain, depending on the translation), a “utopian network of correspondence” in letters and drawings between German expressionist architects and poets linked by a common interest in Scheerbart’s writings and Taut’s architecture. Architects associated with the Glass Chain produced lyrical drawings and proposals such as Carl Krayl’s 1920 “Gleaming House on the Swing”—at once an aerie, crystal, and inverted mountain. Others, such as Hans Scharoun, went on to build monumental crystalline spaces such as the golden Berliner Philharmonie (1957–1963) on the southern edge of the city’s Tiergarten.

The marvelous is not the same in every period of history: it partakes in some obscure way of a sort of general revelation only the fragments of which come down to us: they are the romantic ruins, the modern mannequin, or any other symbol capable of affecting the human sensibility for a period of time.

—André Breton, “Manifesto of Surrealism,” 1924

The space of the grotto is generally understood as an underground chamber—a hollowed-out space or passage, featuring a pool of water, that registers the remnants of water’s erosive force. To the ancient Greeks, the grotto was a spiritual sanctuary, home to deities and oracles, as well as a portal to the netherworld.

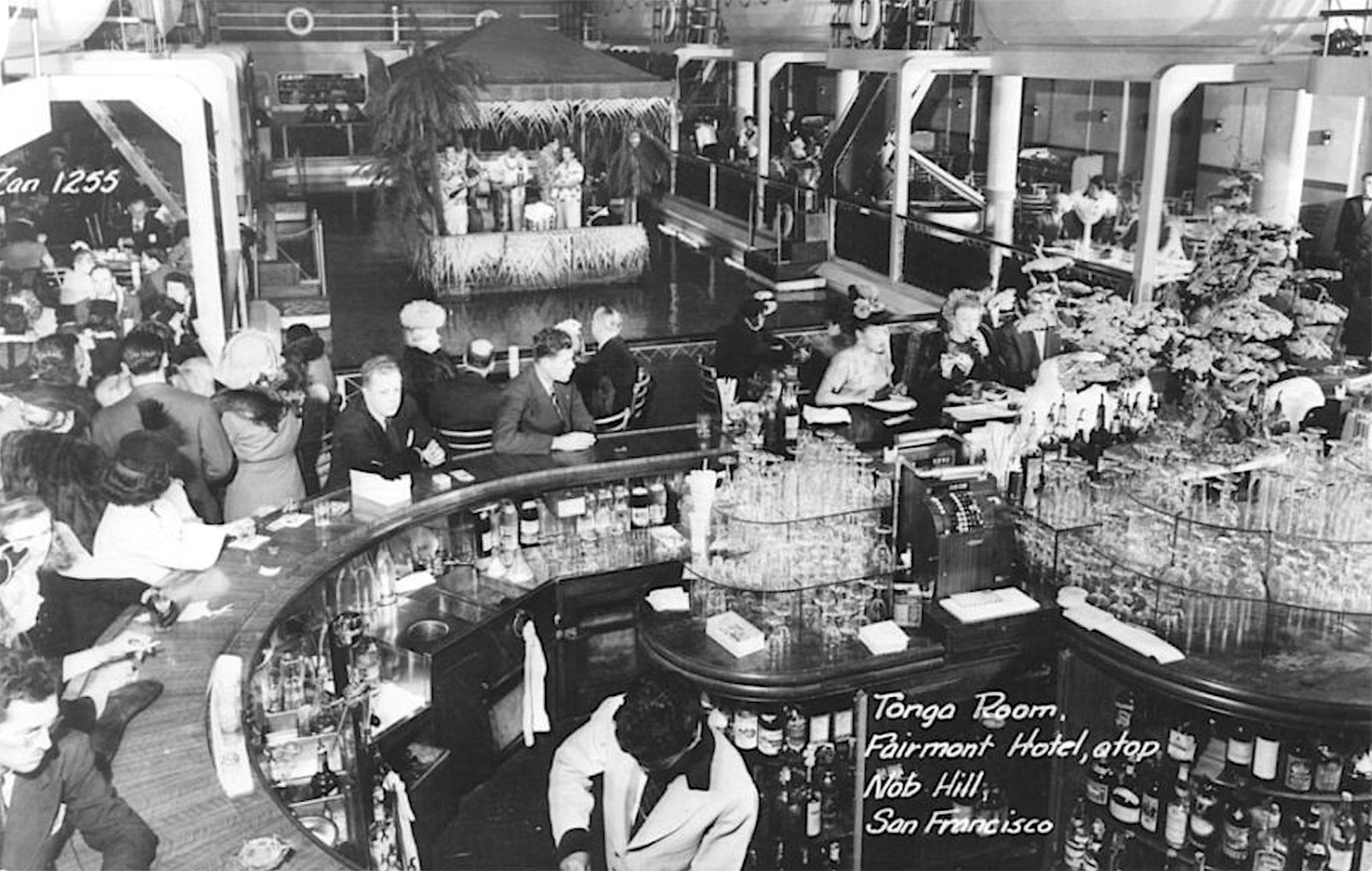

Yet, in its function as a retreat from the world, the grotto can also be a space of artifice, a site for fantasy and theatrical display. The Tonga Room and Hurricane Bar, for instance, is an urban grotto in the form of a subterranean restaurant and tiki bar. Built in 1945 on top of—and entirely coopting—an indoor pool at San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel, the Tonga Room banks on the city’s manufactured identity as a place of adventure, East-West trade, and fortune seeking. Along with Trader Vics, the Tonga Room was one of the first large themed bars to appropriate various signs and symbols from the South Pacific Islands. While Tonga, the site’s namesake, maintained its sovereignty, even as a British protectorate during much of the twentieth century, the Tonga Room traffics more broadly in a mid-twentieth-century fantasy of Polynesian culture, whose exoticism and racist tropes belie the Western military occupation and colonial conquest of the South Pacific Islands, which had been one of the primary theaters of conflict in World War II. The Tonga Room offers an underground tropical paradise, a seeming escape from the city and the neoclassical hotel above. Ersatz nautical motifs, Polynesian carvings, and (since a 1967 remodel) palm thatch–roofed banquettes all encircle a “lagoon.” Hourly storms with sprays of rain, sounds of thunder, and simulated lightning signaled the coming-and-going of a cover band on a party barge—completing the Tonga Room’s air of Pop hallucination. That the Tonga Room endures, and was recently subject to a major “restoration,” undertaken by the firm Gensler, speaks to two moments of cultural appropriation and abstraction that have established its currency, the first being its creation of a subterranean island no-place, the second, generations later, the nostalgia for a “mid-century modern” style that depends on the concatenation of primitivist and futuristic aesthetics.

Even as he is who seeth in a dream,

And after dreaming the imprinted passion

Remains, and to his mind the rest returns not,

Even such am I, for almost utterly

Ceases my vision, and distilleth yet

Within my heart the sweetness born of it;

...

As the geometrician, who endeavours

To square the circle, and discovers not,

By taking thought, the principle he wants,

Even such was I at that new apparition;

I wished to see how the image to the circle

Conformed itself, and how it there finds place;

—Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy: Paradiso, ca. 1320

In architecture it is the model, understood as both verb and noun, that comes closest to guiding the narrative arc of creation. Once used more literally as a term to describe the plans made for a building, modern concepts of the architectural model fluctuate between the linear, allegorical process of using one thing to serve as a pattern for something else, and the more analogical process of creating an object to visualize something that could otherwise never be physically known. Grounded in models, the architect’s creative process differs from the non-linear, associative process of the artist-bricoleur. But in its dependence on the transfer of patterns and its creation of virtual objects to stand in for things otherwise invisible, the architectural imagination is, in its own way, also comparable to the psychological process of dream-formation.

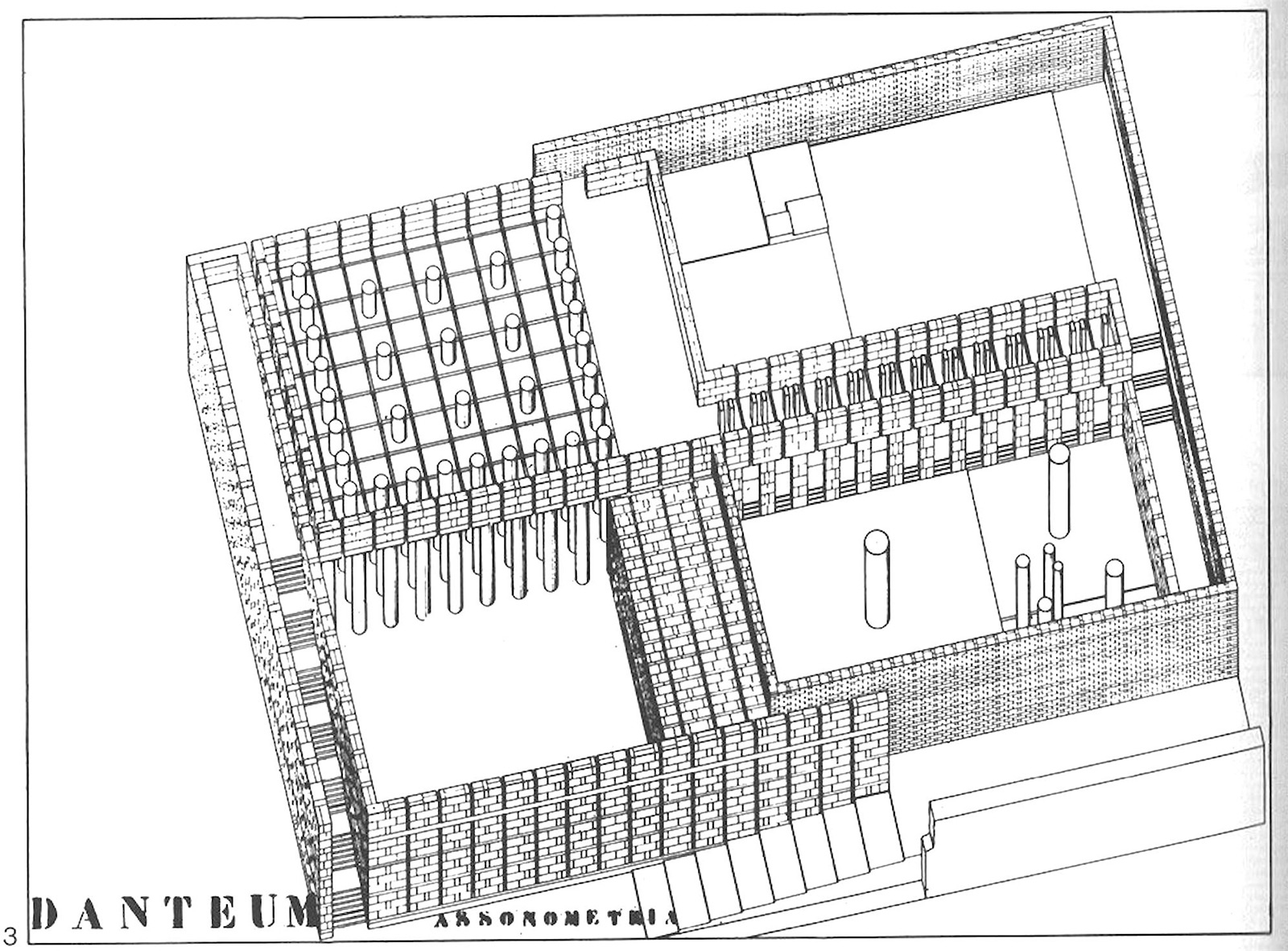

While there are many examples of dreamlike models in architecture, Giuseppe Terragni’s Danteum is unique in the extent to which it understands the model as both transcribed pattern and embodied allegory. Rino Valdameri, a Dante scholar and president of the Società Dantesca Italiana, proposed the Danteum as a monument to the Italian poet in 1938, commissioning Terragni to design the building in time for the Universal Exposition of Rome in 1942. It was to be located along the Via dell’Impero as part of Mussolini’s planned remaking of Rome into the symbolic (in addition to the literal) capital of the Fascist state. While the Danteum received significant support and funding, the course of the war meant that its fate was to remain on paper, including photographs of presentation panels in which Terragni had inserted bas reliefs.

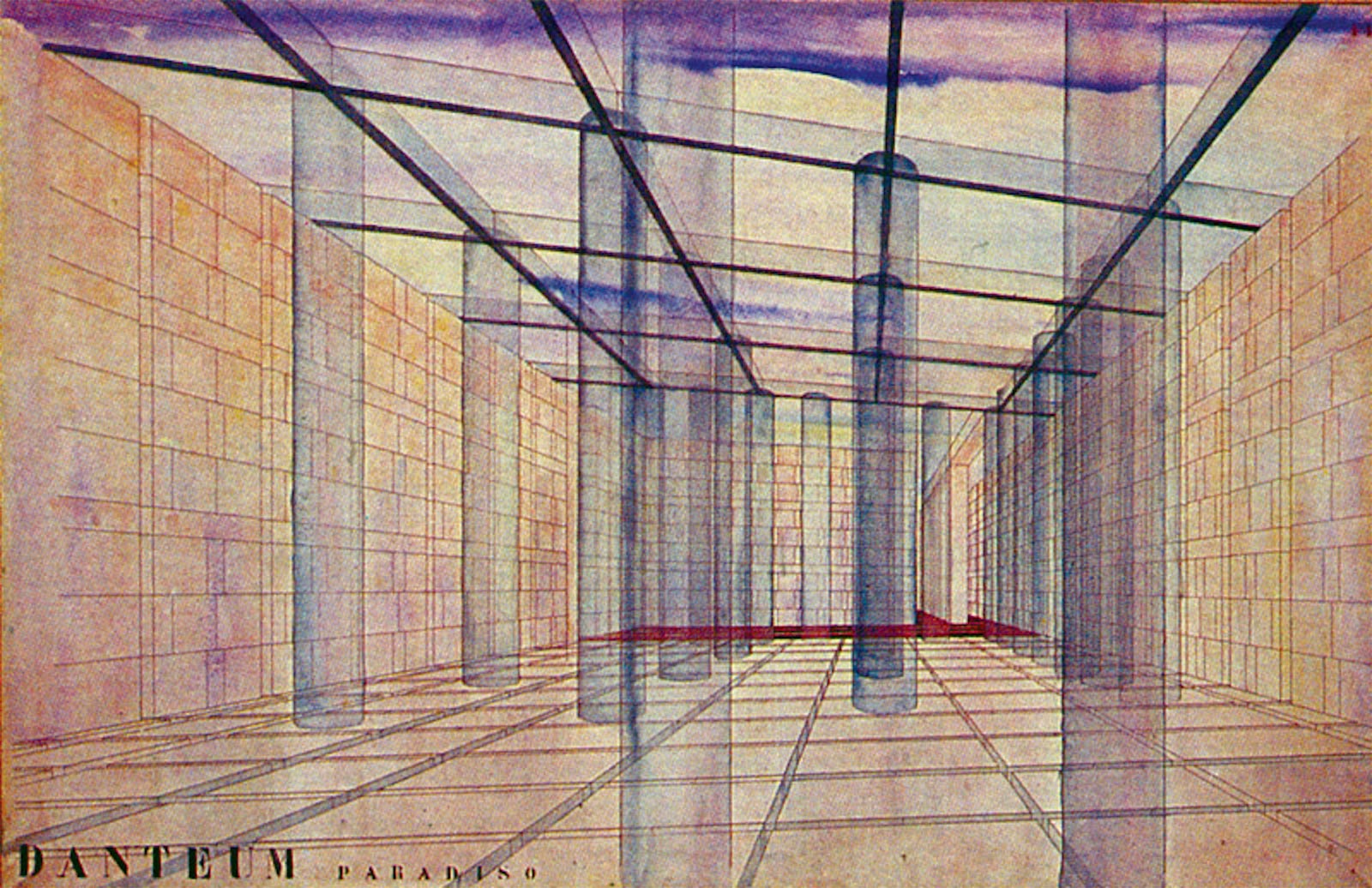

Inspired by the narrative structure of Dante’s Divine Comedy, the Danteum construes a sequence of spaces, beginning with the “dark wood,” then descending through hell, purgatory, and finally ascending to paradise. Terragni eschewed any attempt to illustrate Dante’s story through literal means, instead patterning the project on the rhythm and structure of the text. The intricate numerological pattern of circles and rings that organizes the Divine Comedy is said to have been derived not only from previous theological texts, but from the round architectural form of churches in the Byzantine period. Among the geometric techniques Terragni used to transcribe the order of the text was a mathematical system associated with the Fibonacci sequence and the golden ratio. He deployed these to weave a circular pattern of proportion and movement into what might otherwise have appeared to be modern, Cartesian architecture. In addition to its spiraling form, perhaps the most striking feature of Terragni’s scheme was its material inversions and illusions. For example, in the Paradiso section, watery glass columns hoist a grid of roof beams that frame only a heavenly sky. A hall of mirrored architectures and texts, the Danteum poses a question: given a book inspired by a building, and then a building drawn from a book, where does one begin and the other end?

Space, like time, engenders forgetfulness; but it does so by setting us bodily free from our surroundings and giving us back our primitive, unattached state. ... Time, we say, is Lethe; but change of air is a similar draught, and, if it works less thoroughly, does so more quickly.

—Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, 1924

The mountain aerie shares with glass and crystal an allusion to deep, geological time, a place apart from the linear or cyclical temporalities associated with the cultivated lowlands. Ascending to the sky, it is a perch between the land and the heavens. While the mountain aerie is the antithesis of the grounded grotto, both are among dream architecture’s most powerful spaces of mental projection: grand, more liberated versions of the nightmare-prone basement and attic of the everyday domicile.

Hans Poelzig was an architect of early modernism in Germany, first associated with expressionism, and later with the New Objectivity. He was of an entirely different cast than the light-seeking architects of the Glass Chain, with a distinctly noir sensibility. Perhaps the most telling detail in the biography of this immensely talented and prolific architect is that he designed the extensive sets for one of the first examples of German Expressionism in cinema, the 1920 silent horror film The Golem: How He Came into the World. Later, Edgar Ulmer, one of the filmmakers Poelzig had mentored during the making of The Golem, emigrated to the United States and directed a Hollywood adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat.” In a tribute to Poelzig, Ulmer cast Boris Karloff as Hjalmar Poelzig, a villainous Austrian architect and leader of a satanic cult who in the film wanders through his chambers holding a black cat and overseeing a collection of dead women in glass cases.

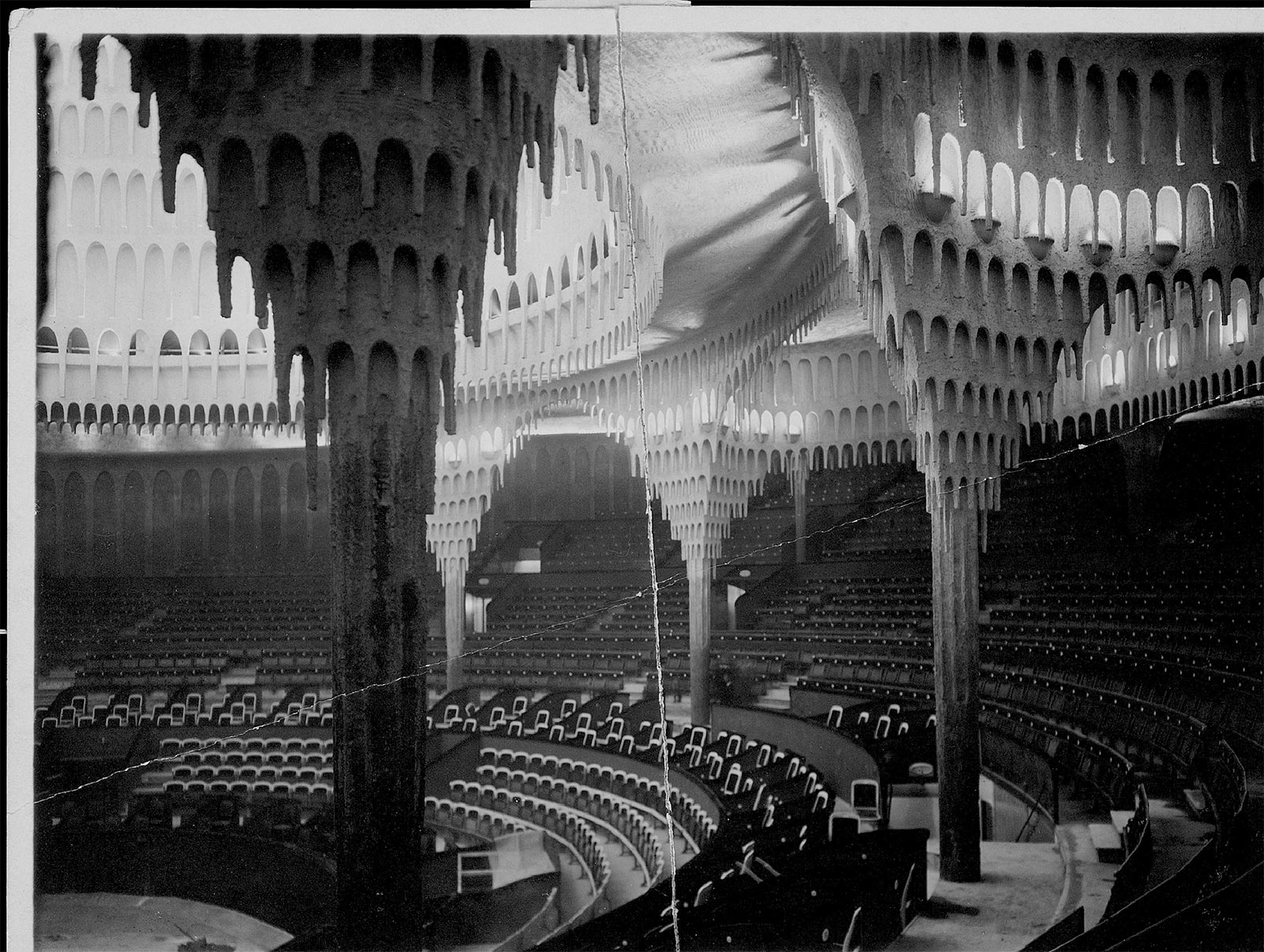

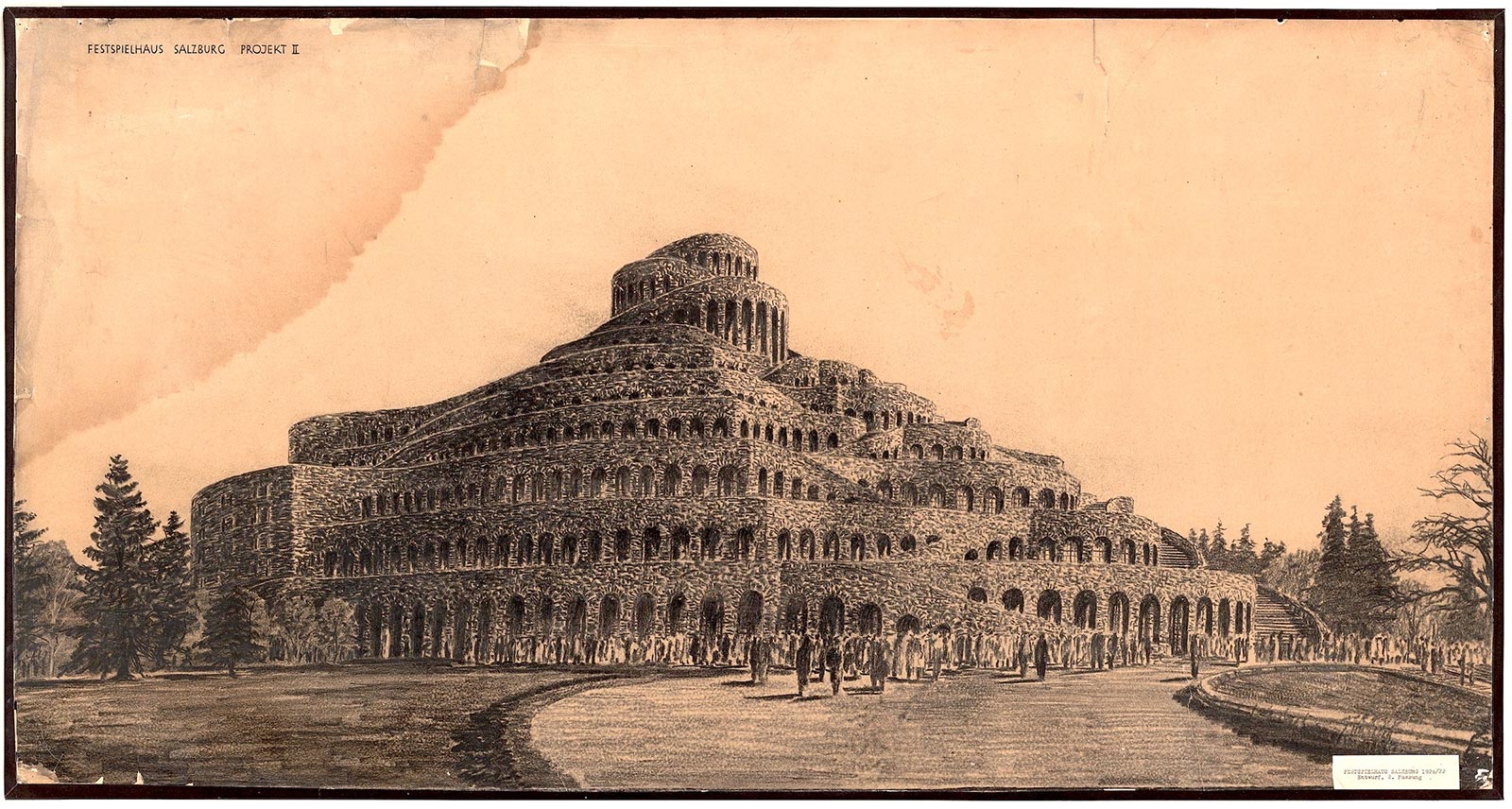

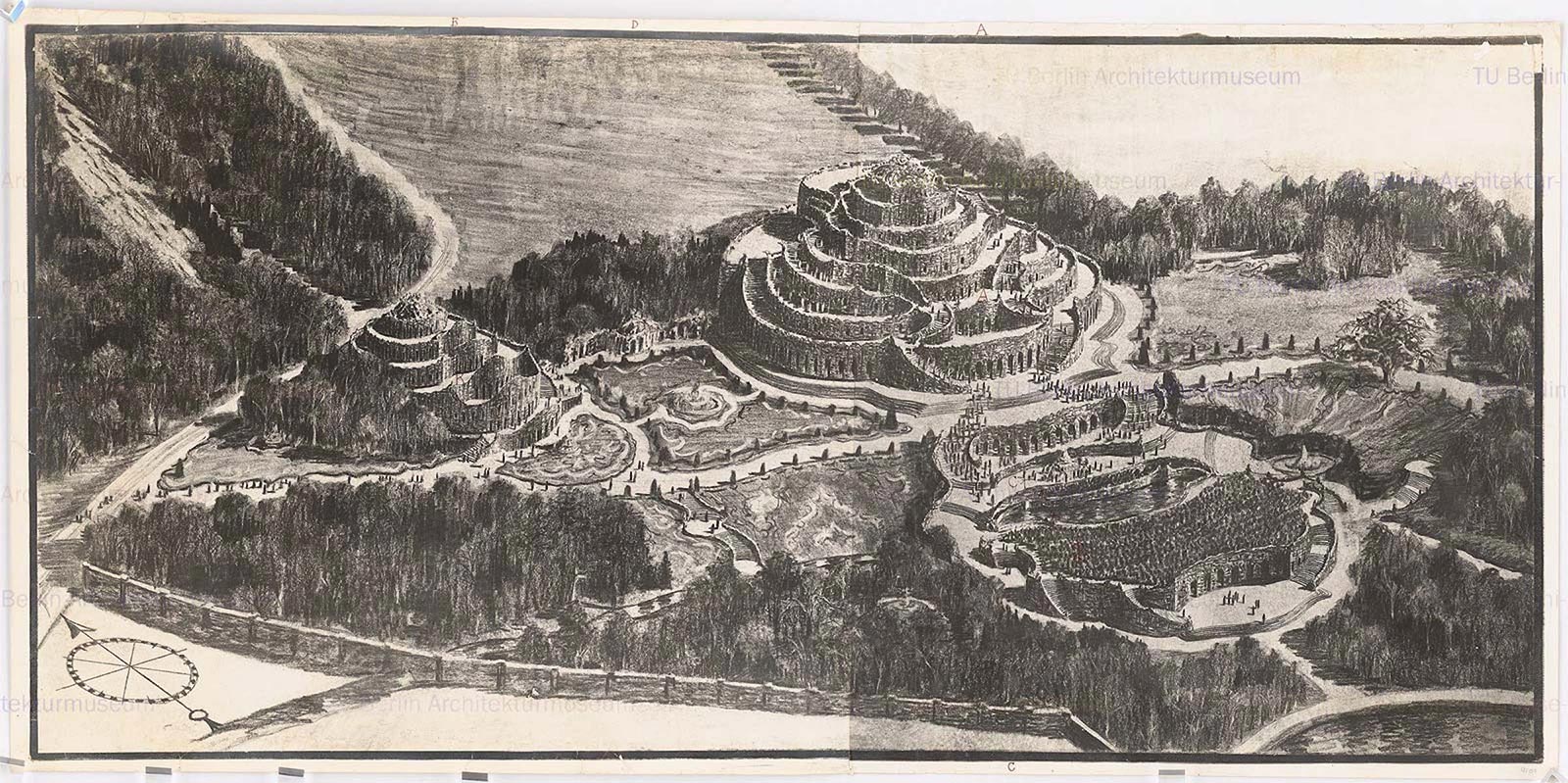

The Golem was directed by Max Reinhardt, a major impresario during the Weimar period, who also commissioned Poelzig to design two of his most striking projects, exemplifying the theatricality and material contradictions of the mountain aerie. The Berlin Grosses Schauspielhaus of 1919 was a crystal, cave-like renovation of an existing interior, and is one of the only built works of architecture from this period to successfully achieve the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk in a modernist idiom. Poelzig’s more ambitious but unbuilt scheme for Reinhardt was the Festspielhaus designed for Salzburg in 1920, a massive complex of two immersive theatres (one with a capacity of two thousand and the other of eight hundred) spun into mountain-like ziggurats with paths ascending to the sky, and cave-like interior studios, workshops, and rehearsal and food halls—all carved into and growing out of an arcaded and terraced landscape.

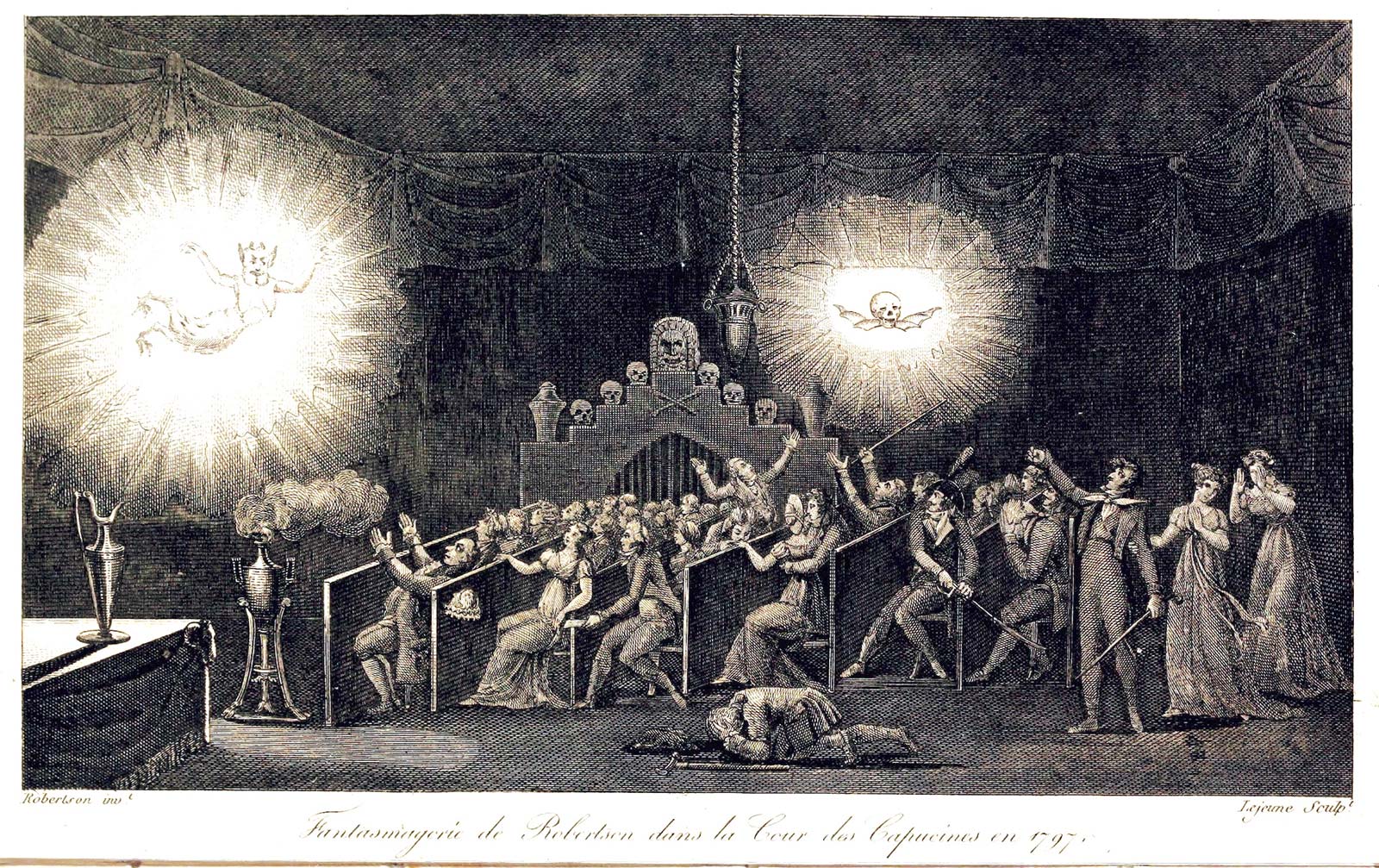

This screen, being half-way between the spectators and the cave which was first shown, and being itself invisible, prevented the observers from having any idea of the real distance of the figures, and gave them the entire character of aerial pictures. The thunder and lightning were followed by the figures of ghosts, skeletons, and known individuals, whose eyes and mouth were made to move by the shifting of combined sliders.

—Sir David Brewster, Letters on Natural Magic Addressed to Sir Walter Scott, 1832

The term phantasmagoria is a portmanteau from Greek combining phantasma, an image, apparition, or figment of imagination made visible, and agora, an assembly or gathering. Popular in the late eighteenth century and across the nineteenth, phantasmagorias were pre-cinematic performances of projected light and shadow with content now understood to belong to the gothic horror genre. Epitomizing the collective desire to experience the supernatural, phantasmagorias were conceived to arouse and frighten spectators with ghost-like apparitions and terrifying images of skeletons, devils, witches, and mummies.

Among the historical predecessors of the phantasmagoria is the camera obscura. A spectacle whose principles have been known since antiquity, the camera obscura simply requires a dark chamber with a pinhole-sized aperture through which light can be refracted in ways that reproduce a remote scene. Projecting an inverted, live image of an exterior world on the intimacy of an interior, the camera obscura conflates scale and inverts context, without the mediations of art or theater. Initially used as an instrument to study astronomical phenomena, then deployed as a drawing device by artists, and finally ending up as a toy-like spectacle commonly found in amusement parks, the camera obscura was essentially a pre-cinematic medium deploying live, optical transfer of content. In each of its historical iterations, the camera obscura is also, in effect, a dream machine. The photographer Abelardo Morell is among those contemporary practitioners of the technique who explore this dreamlike potential. One set of his photographs conflates the intimacy of the domestic bedroom with vast cityscapes, using the pinhole camera to float and distort elements of the city above a bed, as if an (absent) sleeper’s dreams had somehow become visible in the room.

The main device used in the phantasmagoria was the magic lantern, invented in the seventeenth century by Athanasius Kircher. Kircher’s contraption married a large candle to a concave mirror, allowing drawings and other images to be projected. In its artifice and theatricality, it might be said to have anticipated cinema even more than the naturalistic camera obscura. The showman Paul Philidor was the first to call a magic lantern show “phantasmagoria,” in Paris in 1792. (He was also most likely the person performing phantasmagorias in London a few years later under the name Paul de Philipsthal.) Philidor’s performances were followed in 1798 by the “Fantasmagorie” of Étienne-Gaspard Robert, stage name Robertson, an inventor, physician, magician, and showman promoter. In his traveling magic lantern spectacle, he utilized smoke, mirrors, and sound to augment projections of floating phantoms, producing fantastic macabre nightmares to be experienced in the comfort and safety of a communal, darkened theater.

Crystal hung about the neck of sleepers, kept oft bad dreams and dissolved spells of witchcraft. ... The Onyx was believed in the Middle Ages to expose its owner to the assaults of demons, ugly dreams by night, and, worse than these, law-suits by day.

—William Jones, History and Mystery of Precious Stones, 1880

The pillow, by elevating the head off the ground, remains the most essential prosthetic medium for inducing states of sleep and dreaming. The first pillows were carved from stone. These acquired apotropaic powers in ancient Egypt, when miniature stone amulets in the form of headrests began to be placed in the wrappings of mummies in order to ward off evil forces. Significantly, the ancient Egyptian word for headrest (wrs) is related to the word rs, which means both “to awaken” and “to dream,” suggesting that these earliest pillows had an oneiric function.

This early belief in the relationship between stones and dreaming goes beyond their being shaped into pillows. A record of the virtues and imagined attributes of stones and minerals can be found in ancient and medieval lapidary treatises. The treatise De Lapidibus (“On Stones”) by the Greek philosopher Theophrastus (372–287 bc) offered a guide to the therapeutic properties of stones and minerals, often tied to sleep and dreams. The Chinese Ben Cao Gang Mu (“Compendium of Materia Medica”), a twenty-five-volume dictionary of herbs compiled by Li Shizhen (1518–1593 ad), details medicinal drugs and illustrates prescriptions, including the use of stones: for instance, sleeping on jade was believed to cure insomnia and depression, enhance memory, and curtail hair loss. In more recent history, echoes of the lapidary treatise are found in alternative and New Age cultural practices, where the application of stones and minerals to the body is thought to have various oneiric functions. For example, within some New Age healing theories, it is believed that amethyst aids in transitioning from day to night, barite induces dreams and assists in their recollection, hematite promotes lucid dreaming, and rubies can safeguard one from nightmares.

The Cretan Asclas being deaf and unable to hear

the surge of the shore or the roar of the winds,

all of a sudden, after praying to Asclepius, retuned home

able to pick up words even through a brick wall.

—Epigram from Milan Papyrus, ca. 200 BC

The word temple has its origins in Ancient Rome and has the same root as the word template, both related to the consecration of space for ritual purposes. The Latin templum refers to the practices of augurs—priests charged with interpreting the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds—who would stake out, or divine, a sacred space by means of two distinct measures: one marking the ground/earth, and the other framing the relationship with the sky and heavens.

Among ancient and non-Western cultures, dream sharing offered a means of diagnosing and curing medical conditions; it also served to connect, and to prophesize. In ancient Greece, the temple consecrated to this collective activity was the asklepion, a complex of sanctuaries and other spaces for the ritualized staging of dream incubation, therapeutic sleep, prophetic dreaming, and medicinal healing. Dream incubation, or enkoimesis, occurred in the innermost chamber of the asklepion complex known as the abaton or adyton. Supplicants slept collectively in the abaton, a dormitory dedicated to oneiromancy (dream divining), and while dreaming would be visited by the god Asklepios to receive their cure.

Music, arouses a flood of intellectual memories and ideas, which, in their turn, give rise to other and more complicated memories. Music heard during sleep attains the same end. ... The subject is first required to look steadily at a brightly lighted object moved by clock work. … The stage is that of half waking, half sleeping, and the visions control the mind. It is while the consciousness is thus half dead that by music and moving pictures visions are made to order.

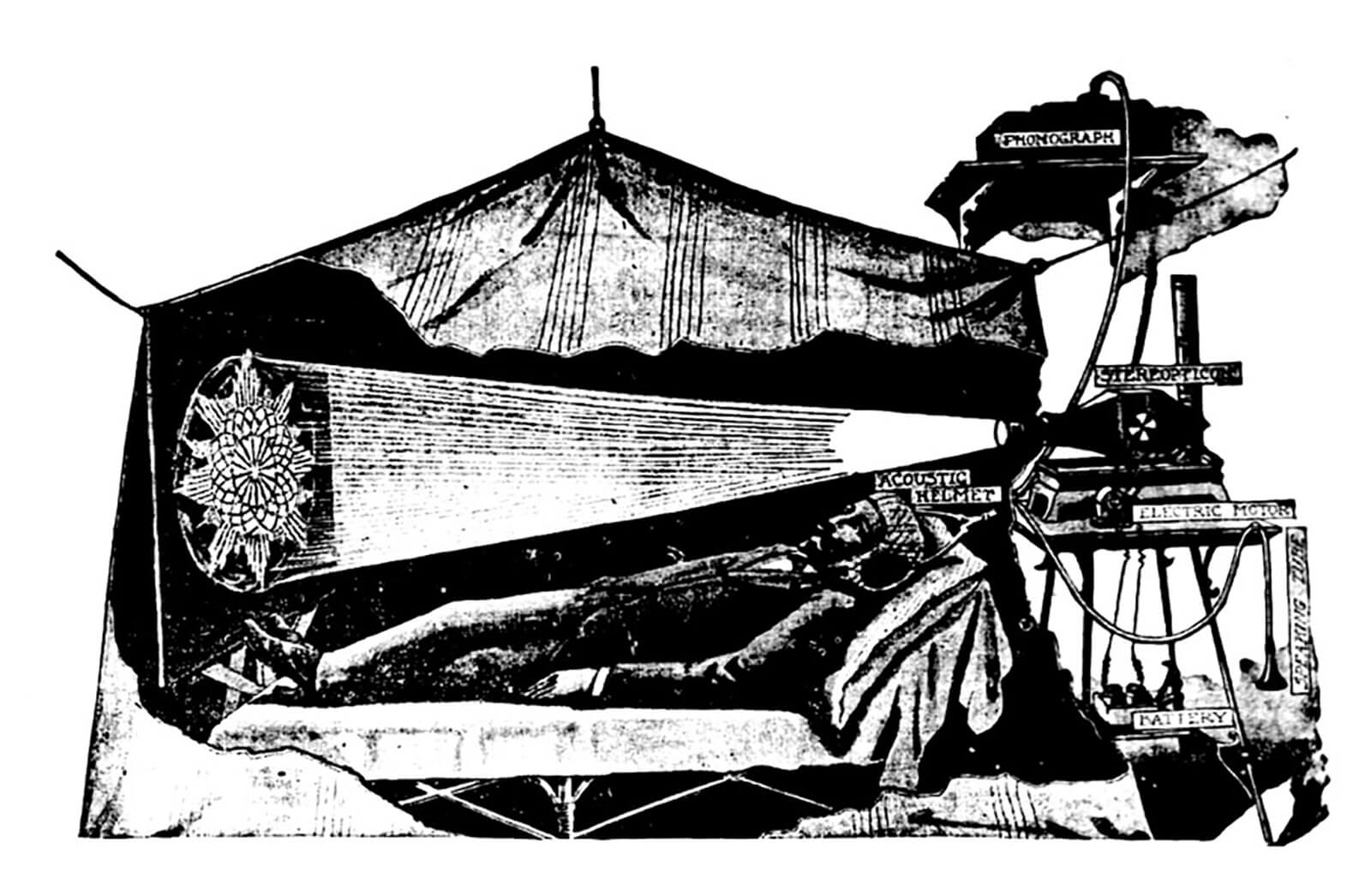

—Dr. J. Leonard Corning, “If You Can’t Sleep Buy a Dream Tent,” 1899

And also, when all was silent in the still hours of night, or during an afternoon sleep, one often noticed, without the appearance of any external cause, oscillations, as it were spontaneous changes of locality of the blood, arising from dreams or psychic conditions acting on the vaso-motor nerves and modifying the circulation, without the participation of consciousness, or at least without a trace of these processes remaining in the memory.

—Angelo Mosso, Fear, 1884

The bed, in all its historical incarnations, is among the most basic of human furnishings. As a site of various human cultural practices—not just sleep—it follows that in the modern era, the bed became a site of scientific experimentation and medical treatment. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Dr. J. Leonard Corning, an American neurologist, proposed “treating nervous excitability and kindred ailments by the induction of pleasing dreams” through the assembly of an unprecedented space—a sleep laboratory. Utilizing objects and furniture typical of nineteenth-century parlor culture, Corning constructed the makeshift mobile laboratory by draping a large tarp around a divan in order to create a dark private chamber. To instill a state of drowsiness in the patient, a stereoscope projected patterns of colored light while an Edison phonograph, attached to a specialized leather nightcap with rubber tubing, played music with minor chords and arpeggios, or, alternately, selections from the operas of Richard Wagner. Corning contended that in a state of pre-sleep and sleep, the patient’s consciousness becomes dormant and the unconscious receptive to the effects of “musical vibrations,” thereby inducing pleasant dreams and contributing to the elimination of unwanted and aberrant thoughts upon waking.

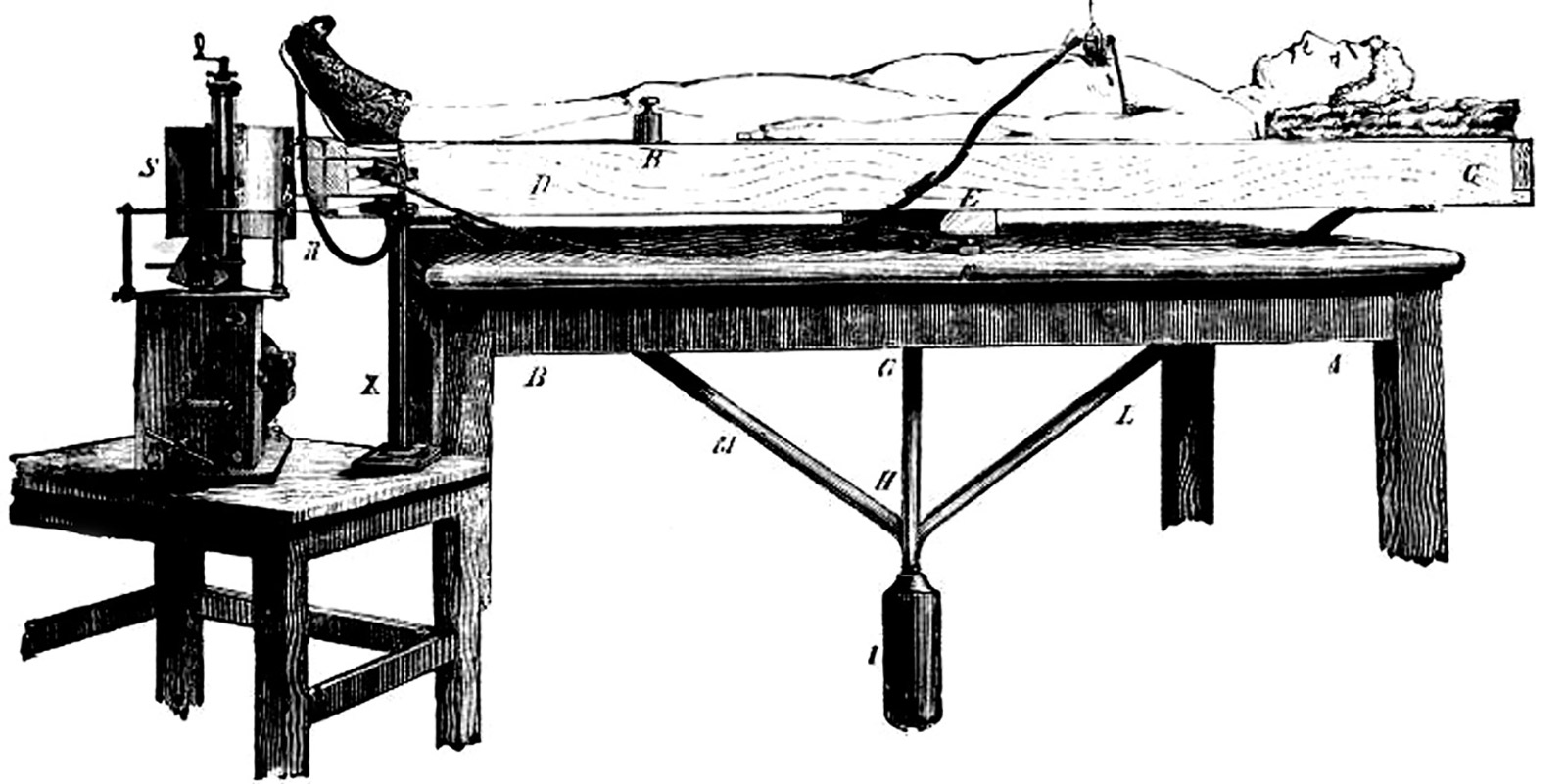

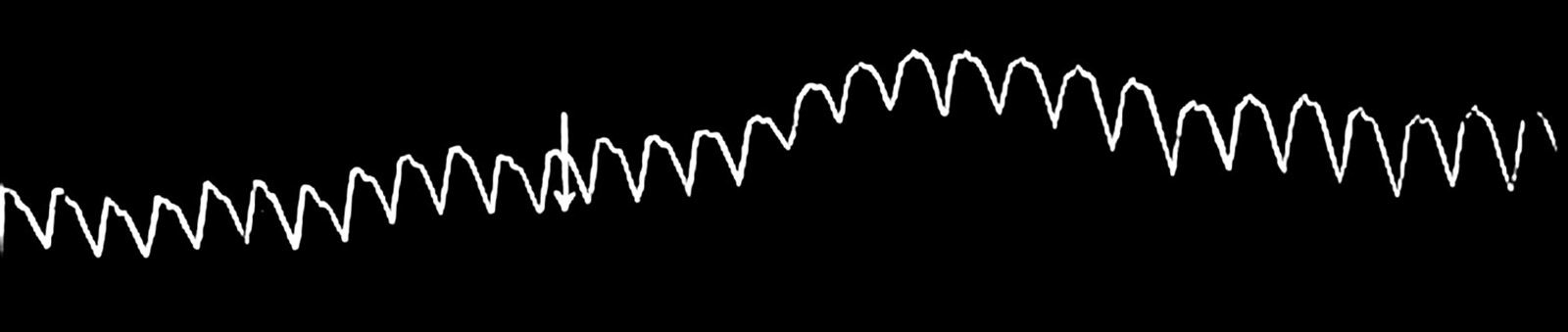

Another late nineteenth-century use of the bed as a site of human experimentation was the “human circulation balance.” Conceived and designed by the Italian physiologist Angelo Mosso, the machine measured cerebral activity during rest and during various mental exercises. It can be considered a precursor to contemporary neuroimaging machines such as the EEG and MRI. Essentially a padded wooden bed on a fulcrum, the balance acted like a seesaw. Equipped with a variety of measuring devices, it tipped back and forth in response to the flow of blood within the body and recorded related physiological processes such as breathing, pulse, and movement. Mosso not only measured the active brain in states of wakefulness but equally applied his “scientific cradle” to the sleeping brain. In yet other experiments, he produced some of the earliest graphic mapping of a dream.

Below: This graph, dating from 27 September 1877, records the “brain-pulse” of one of Angelo Mosso’s subjects; the arrow indicates the moment when Mosso approached the sleeping man and whispered his name. Images from Mosso’s book La Paura (Fear), 1884.

I think that cars today are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals: I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object.

—Roland Barthes, “The New Citroën,” Mythologies, 1957

The mental and philosophical benefits of wandering are well-understood within nomadic and indigenous cultures; the need for perambulation also informed the architecture of settled, classical societies. With the advent of modernity (especially in liberal states aspiring to democracy), the opportunity—and right—to move freely, with or without purpose, across urban or rural territory, became an important aspect of social mobility and emancipation. Accelerating what boats and horses had done for millennia, modernity’s new technologies of mobility—bicycles, trains, automobiles, and planes—changed the time and space of travel, and created new, wandering-induced subjectivities and dreamscapes.

Any object that embodies, enables, or represents movement also offers a vehicle of psychological transport akin to the mental experience of drifting into sleep and dreams. The concept of the dérive (French for “drift”), developed by the Lettrist International and its leader Guy Debord, was the most prominent theory to celebrate the radical political potential of free, unconscious movement and chance encounter. Debord and his colleagues wanted to break social strictures and counter the commodification of consciousness that threatened to overtake society in the latter twentieth century by a form of unplanned wandering through the urban landscape. Their theories and actions were in some ways the European counterpart to the American Beats’ let’s-get-lost and on-the-road credo that so shaped the postwar cultural sensibility.

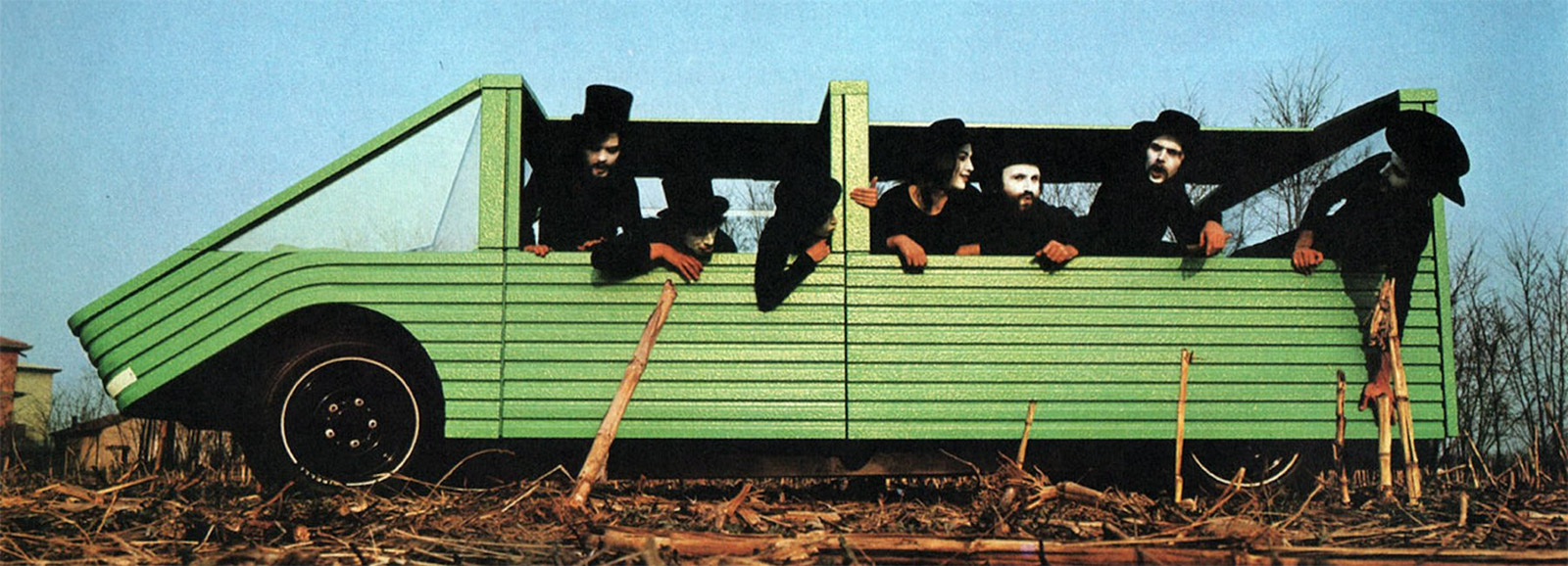

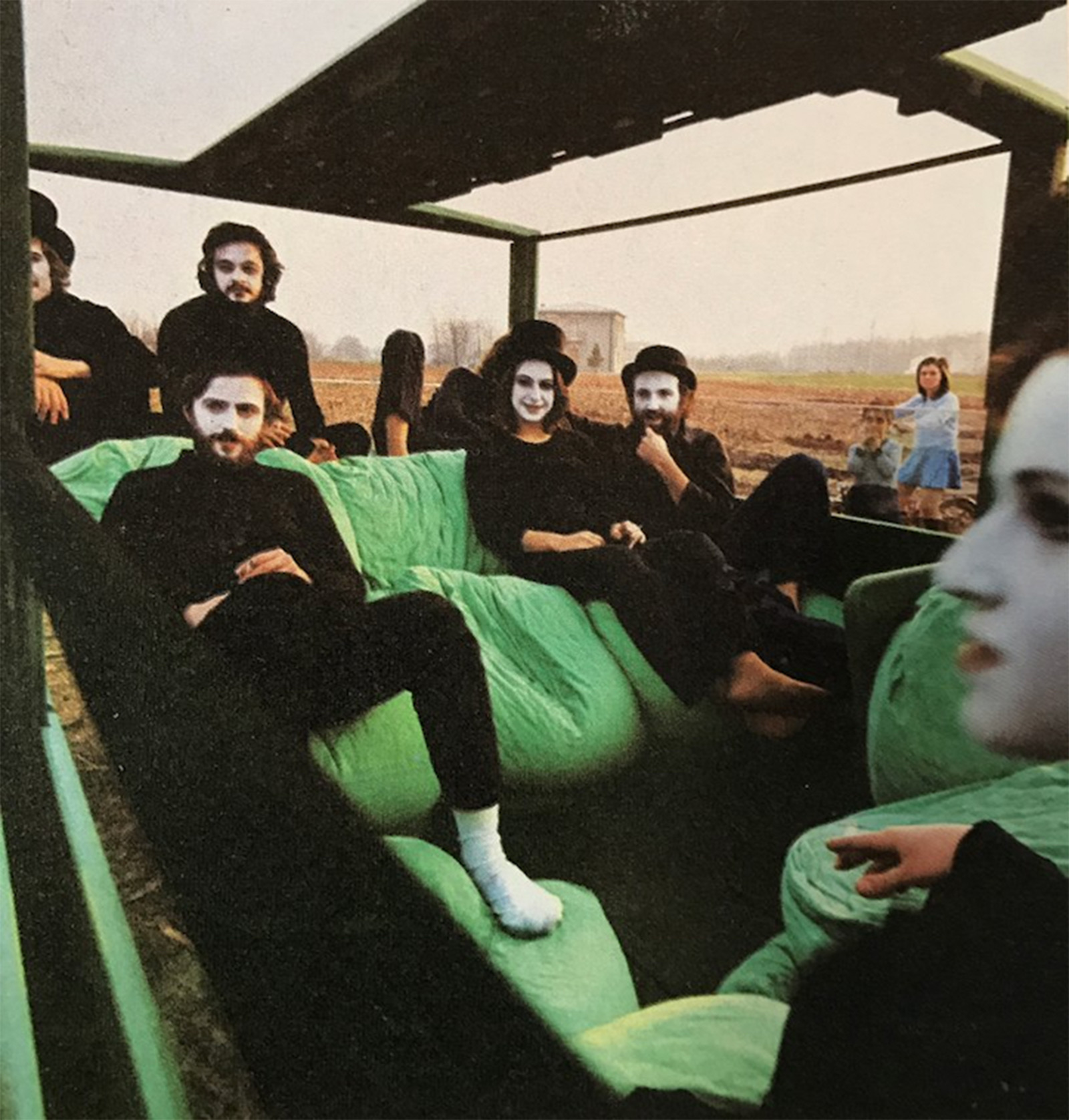

Mario Bellini’s 1972 Kar-a-Sutra is among the works of art and design that are a play on the lettrist (and later situationist) dérive. A sixteen-foot-long and six-foot-wide “concept car” whose name evokes the Kama Sutra, the ancient Indian Sanskrit guide to the sensual art of living pleasurably, the Kar-a-Sutra offered an antidote to the tyrannical culture of the automobile. Subverting the typical focus on origin and destination, the Kar-a-Sutra was more an adventure-utility-vehicle than a car. Dedicated to free play and open to the sky, Kar-a-Sutra drew on, but was more openly scripted than, the camper, RV, Jeep, Land Rover, and hippy van. Kar-a-sutra was a “mobile human space” with a flexible cushioned interior, designed for a collective life spent drifting on wheels, one not limited to a prescribed path, or the itinerary and amusements of existing roadways. In the Kar-a Sutra, one could mime, or dream, a new way of life.

Also banking on the absurdist impulses of lettrism and situationism, but more explicitly political than the Kar-a-Sutra, was Krzysztof Wodiczko’s 1973 Vehicle. Wodiczko started as an industrial designer in communist Poland, only later becoming known as a canny artist of “vehicles” and “projections.” A sculpture base and soapbox married to a bicycle mechanism, Vehicle is propelled forward by the operator/driver (the artist himself) who triggers a seesaw motion by walking back and forth. Wodiczko’s work is akin to both the dérive and yet another lettrist concept, détournement—the recombination of preexisting material to subvert its intended message. Wodiczko paces aimlessly on his four-wheeled pedestal, which can only advance on the ground in a straight line, confronting society with the anxiety, or futility, of being required to “move forward” when real progress is not possible.

To disappear into deep water or to disappear toward a far horizon, to become part of depth of infinity, such is the destiny of man that finds its image in the destiny of water.

—Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter, 1942

… down there in the deep place, with her hair waving soft and lazy like meadow grass under flood water, and that slit in her throat, like she had an extra mouth.

—James Agee, screenplay for The Night of the Hunter, 1955

As a primordial substance, water is a common, chimerical element of dreams. On its surface, water reflects forces and events, masking an otherworldly domain below. Water’s mercurial juxtaposition of surface and depth figures prominently in the 1955 film The Night of the Hunter. Based on Davis Grubb’s 1953 novel of the same name, the film chronicles a serial-killer pretend-minister’s pursuit of two children along the Ohio River and the children’s journey to safety. Told primarily from the children’s point of view, the film is a fairy tale of good and evil whose mesmerizing quality evokes the hyperreality of a dream. The river offers a means of escape and safe passage for the children. As their boat drifts along with the current, they daydream, unaware of the terror at the bottom of the river—the body of their murdered mother, trapped in a Ford Model T.

Natalie Fizer is a partner in Pillow Culture, a multidisciplinary studio in New York City dedicated to the development of pillow prototypes and spatial paradigms for the slumbering body. Recent projects include “TEST BED: A Modern Abaton” at the New School in 2018, which offered a contemporary look at ancient Greek therapeutic sleep temples, and “New Circadia: Adventures in Mental Spelunking,” a collaborative project at the University of Toronto in 2020 that addressed technological distraction and restorative boredom. Pillow Culture’s current project involves a radical rethinking of the sleep aid.

Richard Sommer is a professor of architecture and urbanism, and director of the Global Cities Institute at the Daniels Faculty, University of Toronto. His writings on time-based architecture include “The Democratic Monument: The Reframing of History as Heritage” (co-authored with Glenn Forley), which appeared in the edited anthology Commemoration and the American City: Monuments, Memorialization and Meaning (University of Virginia Press, 2013). He is currently collaborating on a project and exhibition entitled “Toronto Housing Works,” which will be on view in the spring of 2021.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.