This Land Is Your Land

Native minstrelsy and the American summer camp movement

Asa Seresin*

Ernest Thompson Seton, the English-born pioneer of outdoor education who cofounded the Boy Scouts of America, spent his adult life in a juvenile world of his own invention. The son of a selfish and abusive father, he found escape in playing Indian, a pastime he later celebrated in the wildly popular 1903 book Two Little Savages: Being the Adventures of Two Boys Who Lived as Indians and What They Learned. The book begins by describing a character with striking similarities to Seton himself: “Yan was much like other twelve-year-old boys in having a keen interest in Indians and in wild life, but he differed from most in this, that he never got over it. Indeed, as he grew older, he found a yet keener pleasure in storing up the little bits of woodcraft and Indian lore that pleased him as a boy.”[1]

Seton would go even further, making Native minstrelsy a pervasive feature of American summer camps. In 1902, at the age of forty-one, he had established the Woodcraft Indians in the hundred-acre backyard of his estate in Cos Cob, Connecticut. An outdoor boys’ club and precursor of the Boy Scouts, it became the seed of a movement whose laws, practices, and principles Seton meticulously documented in dozens of texts, including The Red Book, or How to Play Indian (1903), the Boy Scouts’ Handbook of Woodcraft, Scouting, and Life-craft (1910), The Gospel of the Redman (1936), and The Book of Woodcraft and Indian Lore (1912), updated on a yearly basis and nearly six hundred pages in length, with “over five hundred drawings by the author.” His romantic appropriation of Native culture would have a decisive impact on American childhood, and through it on the evolution of white American identity.

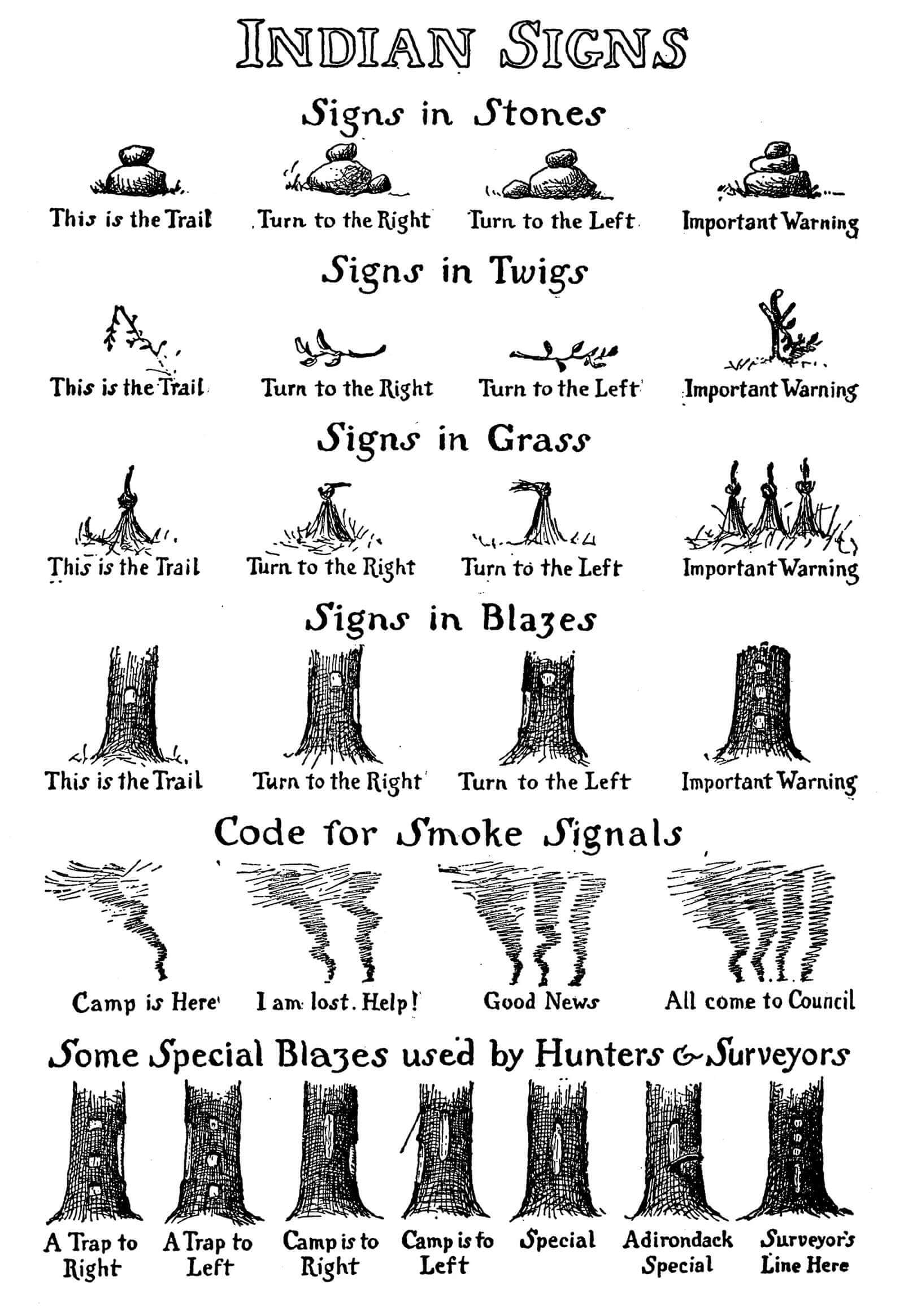

Native play was not simply an amusing feature of the Woodcraft Indians; it was the practice around which the entire organization was based. Campers were sorted into tribal hierarchies with positions like Head War Chief, Wampum Chief, Chief of the Painted Robe, and Chief of the Council-Fire. The boys had the opportunity to “win” Indian nicknames based on their contributions to the camp. “Grey-wolf was the best scout,” while “Eel-scout was the one who slipped through enemies’ lines as often as he pleased.”[2] Campers participated in battles, council meetings, and prayer circles, as well as Scalp Dances, Peace Pipe Ceremonies, and other performances. They learned words, songs, and war cries from a mishmash of different Native languages. They lived in tepees, constructed totem poles, paddled canoes, and mastered smoke-signal systems.

Seton did not consider white men appropriate role models for young boys learning to relate to the American natural landscape. “To exemplify my outdoor movement, I must have a man who was of this country and climate,” he writes in The Book of Woodcraft’s 1912 edition. “I would gladly have taken a man of our own race, but I could find none. ... There was but one figure that seemed to answer all these needs: that was the Ideal Indian of Fenimore Cooper and Longfellow.”[3]

Seton’s Indian exemplar responded to a climate of fear about urbanism, materialism, and secularization from which the American summer camp movement emerged in the 1880s. “[Boys] are made bad by evil surroundings during the formative period between school and manhood,” Seton argued.[4] Encounters with the untainted wilderness and “visual tropes of folk life” were assumed to have a redemptive effect on pale and weak city-dwelling children, rescuing them from the threat of “dying of indoorness.”[5]

The sentimental embrace of outdoor life may be one of the best-documented cultural trends of the nineteenth century, but the back-to-nature movement’s racial dimensions are often overlooked. As Abigail A. Van Slyck explains in A Manufactured Wilderness, summer camp served to bolster the “American” values and identities of native-born white settlers, particularly those who were middle class and northern European in origin.[6] Camps reaffirmed the dominant social position of such families, who felt threatened by a massive, multiethnic wave of immigration that destabilized already uncertain notions of Americanness. Patriotism infused summer camp life, from the Boy Scout oath of “duty to my God and country” to ceremonial reenactments of tableaus from American history. Perhaps most importantly, camp encouraged the ritualistic appropriation of Native culture in service of an illusory “white indigenous” identity.

Becoming white by playing Indian might seem like a paradox. But it was part of a larger effort to reinvent people of European descent as autochthonous Americans, obscuring the nation’s status as a settler-colonial state. “Indianness provided impetus and precondition for the creative assembling of an ultimately unassemblable American identity,” Philip J. Deloria argues in Playing Indian (1998).[7] Not accidentally, the rise of American summer camps coincided with the subsidence of the Indian Wars, the closing of the frontier, and the perceived end of the “Indian threat” in the last decades of the nineteenth century. No longer at war with America’s indigenous occupants, whites had to improvise an organic relationship to the territory they had conquered, legitimating themselves as the country’s rightful inhabitants.

“America owes much to the Redman,” Seton writes in The Book of Woodcraft. “He can teach us the ways of outdoor life, the nobility of courage, the joy of beauty, the blessedness of enough, the glory of service, the power of kindness, the super-excellence of peace of mind and the scorn of death. For these were the things that the Redman stood for; these were the sum of his faith.”[8] While elsewhere Seton appears more sympathetic to the pervasive contemporary belief that Native Americans were the “children” of the human race, here he posits “the Redman” as a benevolent parental figure graciously bestowing his wisdom from beyond the grave. As Werner Sollors writes of the noble savage’s deathbed speech, an American literary commonplace: “The Indian speech functions as the departing chieftain’s last will and testament to his paleface successors and resembles a parent’s last wish for a child.”[9] The paradoxical figure of the Native who is at once a naive child and an ailing parent reinforces white unwillingness to see Native people as real, autonomous adults.

Separated from their families in the artificial environment of summer camp, settler children were ritualistically inducted into a hybridized white-indigenous identity premised on a fantasy of kinship with Native Americans. This is similar to the kinship fantasy that Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang call “settler nativism,” a phenomenon wherein “settlers locate or invent a long-lost ancestor who is rumored to have had ‘Indian blood’” in order to absolve themselves of guilt over the genocide of Native people and the continued occupation of Native land.[10] Unlike settler nativism, however, the mythic identity of white indigeneity did not even require a connection to actual Native people, but rather a simulation of the connection Native people actually have to the land. Although this practice outgrew and outlasted both Seton and the Woodcraft Indians, it is partially thanks to him that many white Americans have come to feel—if not quite believe—that they are indigenous to the land they occupy.

• • •

Imagine being a settler child, born in an American city and sent off one summer to Camp Wohelo or Camp Wo-Chi-Ca. It must have sounded like a trip through a wormhole, back to a precolonial world previously glimpsed only in craft-paper form during US history class. At first, it might not have been obvious that Wo-Chi-Ca stood for “Workers’ Children’s Camp,” or that Wohelo was an abbreviation of “Work, Health, Love”—names perhaps better suited to dystopian labor camps than wilderness retreats. White camp organizers had an uncanny ability to invoke Native American culture in a manner devoid of real meaning.

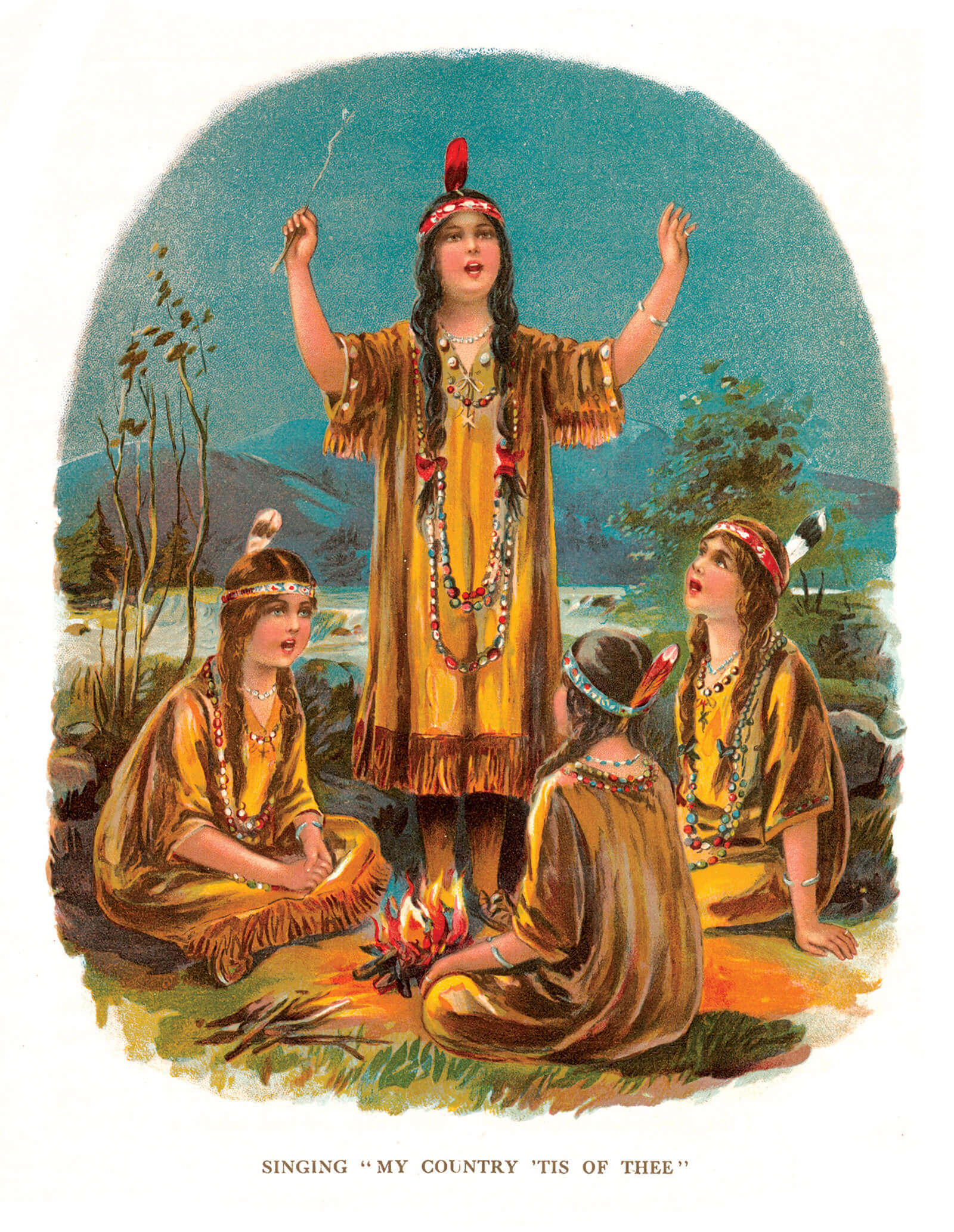

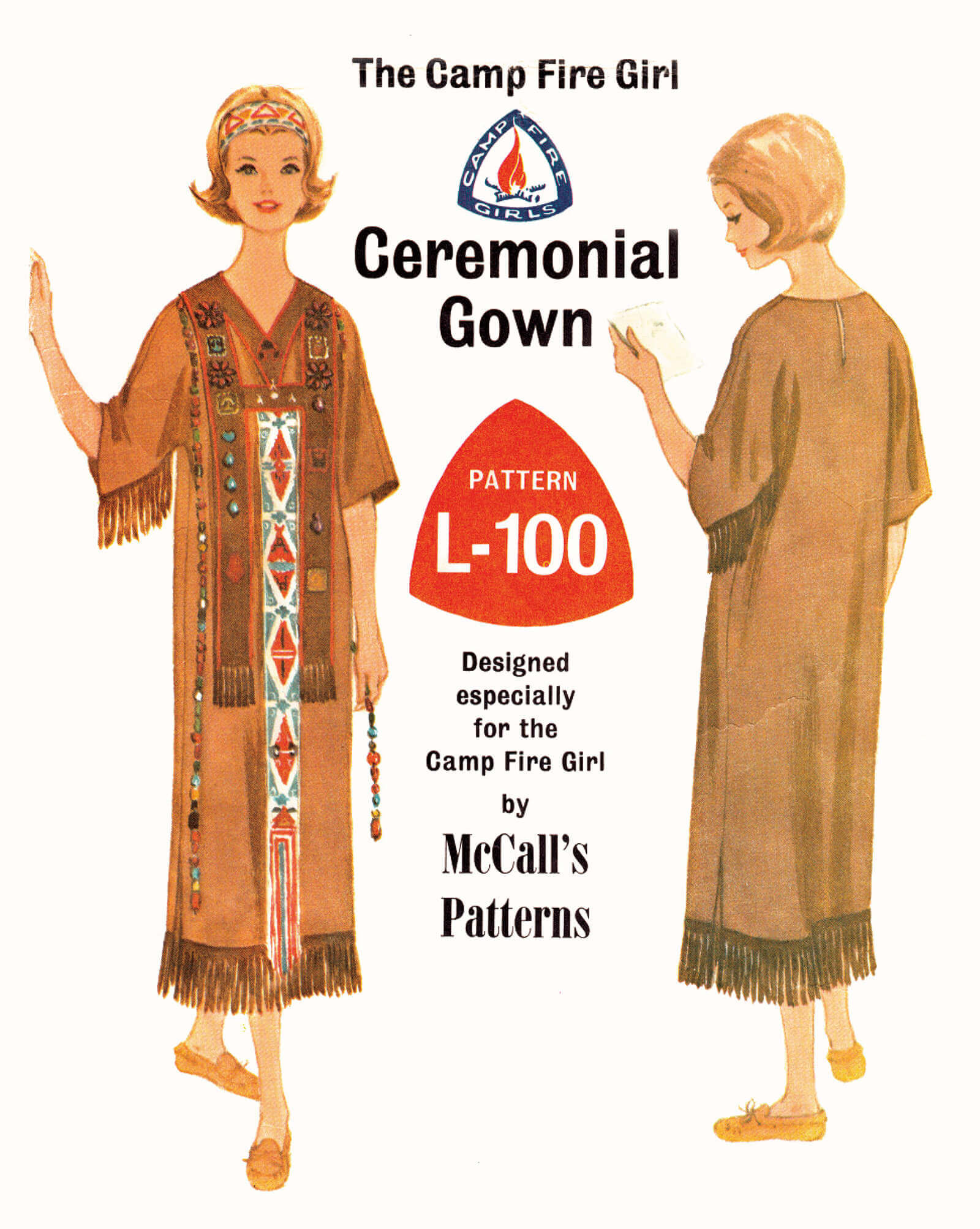

At many camps, children were sorted into tribes and given “Indian names” upon arrival. Florence M. Poast’s Indian Names: Facts and Games for Camp Fire Girls (1916)—which is “affectionately” dedicated to “the little Indian children from whose forefathers we obtained the land in which we live”—provided an extensive list of names (with meanings and pronunciations) from which white girls were encouraged to pick whichever they felt suited them.[11] Although “no one, presumably, wanted to encourage the resurgence of a primitive masculinity in girls,” Native minstrelsy was nonetheless also common among female campers.[12] This was particularly true of the Camp Fire Girls, an organization established in 1910 by Charlotte Vetter Gulick and her husband Luther Gulick, owners of Camp Wohelo in Maine, with help from Seton and his wife, Grace.[13] Written for the Camp Fire Girls, Poast’s book includes glossaries for naming boats, bungalows, and entire camps, as well as mottoes translated from the Narragansett, Iroquois, and Delaware languages. Almost all of Poast’s names refer to the natural world, and while the aim of this was likely not to inspire a rugged wildness in the girls, it is another example in which white settlers used indigeneity as a conduit to identification with the American natural landscape.

The language games settler children learned at summer camp reinforced the idea that Native languages were no longer spoken by living people, that they were simple enough that children could use them without actually learning them, and that they could be effortlessly adapted to describe reality as the colonizers saw it. In Sign Talk: A Universal Signal Code, Without Apparatus, for Use in the Army, Navy, Camping, Hunting, and Daily Life (1918), Seton drew on his supposedly expert knowledge of “the gesture language of the Cheyenne Indians” in order to develop a sign language that he hoped would be adopted across the globe.[14] Seton’s willingness to abstract Plains Sign Talk—which he falsely attributed solely to the Cheyenne people, but which was in fact a method of intertribal communication—was indicative of the way that Native languages were casually appropriated and, by extension, of how indigeneity was made available to campers to inhabit at will.

The body was also an important conduit to indigeneity. In order to achieve the highest grade of membership in the Woodcraft Indians—that of “Tried Warrior”—boys not only had to master outdoor skills and demonstrate knowledge of the natural world but also get “sunburnt to the waist.”[15] This was a rather extreme variant of encouraging white children to tan at camp, a physical transformation widely seen as evidence of health and harmony with nature. Of course, as Leslie Paris writes in Children’s Nature: The Rise of the American Summer Camp, it was crucial that the “whimsical hybridity [of a tan] could be reversed … that the tan would fade was what made it so useful as a symbol of transgressive regeneration.”[16]

Even for Seton, suntans and “Indian names” at summer camp were never meant to erase the distinction between white children and Native Americans. In fact, such performances actually served to reinscribe racial difference. Theorists of minstrelsy have long asserted that racial mimicry must be unconvincing in order to serve its purpose in upholding white superiority. Eric Lott captures this through the idea of the “seeming counterfeit,” “a means of exercising white control over explosive cultural forms as much as it was an avenue of racial derision (though to say the one is perhaps also to say the other).”[17] As Paris notes, early summer camps often featured Indian masques in which campers “painted their skins bronze” and minstrel shows in which the children wore blackface. At the end of Jane L. Stewart’s 1914 children’s novel The Camp Fire Girls in the Woods: Bessie King’s First Council Fire, a performance of Indian dances becomes an ironic assertion of white supremacy: “No Indian girls ever danced with the grace and beauty that those young American girls put into their interpretation of the old-fashioned dances.”[18] Dances end and tans fade, but the metaphor of white indigeneity reinforced by these rituals has proved more lasting.

• • •

Part of the reason Indian minstrelsy became so prevalent in summer camps is that children and indigenous cultures were seen as a self-evident pair. According to turn-of-the-century psychologist G. Stanley Hall’s recapitulation theory of child development, children began life as “savages” before maturing into “civilized” adulthood. As Kevin C. Armitage notes, it was thought that “growing children repeated the evolutionary history of the human race,” and as a result, “teachers needed to use educational materials that coincided with the child’s development.”[19] Seton embraced Hall’s theory of recapitulation and would fondly refer to his campers as “savages” to demonstrate this point.

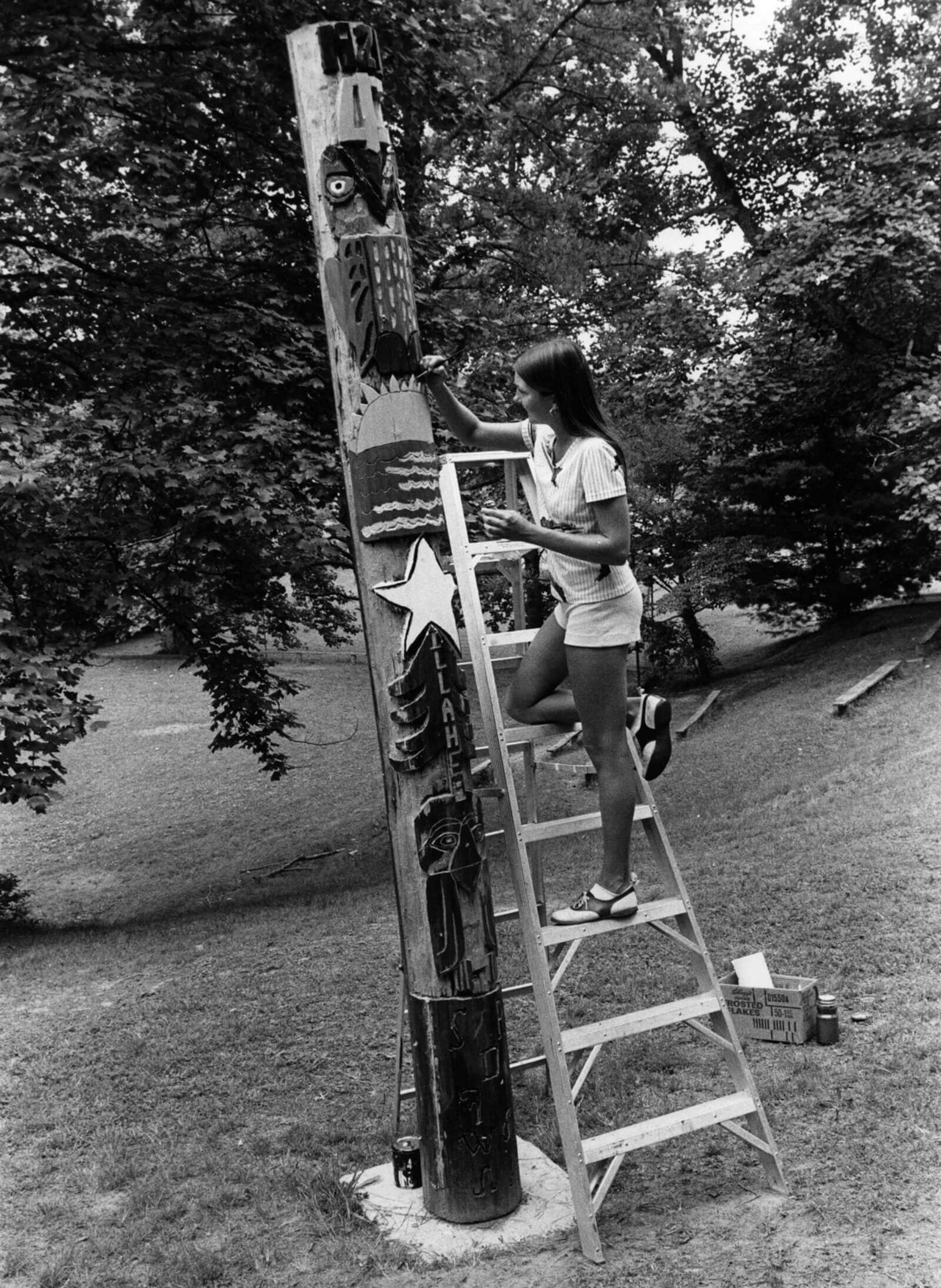

Other camp leaders emphasized white children’s own enthusiasm for assuming Native identities. In 1956, Mary Hanwiler wrote that campers “seem naturally to fall into [the Indian’s] way of living, gradually begin to understand the ideals the Indian fought for, and unconsciously ‘inherit’ his love for nature, the forests and its inhabitants.”[20] The notion that children, like Native Americans, were “born naturalists” encouraged forms of Indian play that revolved around interactions with the natural landscape, such as canoeing, horse riding, carving totem poles, sleeping in tepees, and building campfires.[21] Such ventures constituted what Seton and other camp leaders described as “the ideal outdoor life” for which Native Americans served as the premier example.

The summer camp movement collapsed Native American cultures into superficial modes of life that could be imitated and “mastered” even, or perhaps especially, by the very young. Native-inspired rituals, objects, and games, evacuated of more complex meanings, became available as therapeutic ornaments. Bernard Mason, an influential leader of the summer-camp movement and long-presumed authority on “Indian lore,” claimed: “Totem Poles may have meant many things to the savage mind [but they] are mighty strong medicine for boys and girls. Grotesquely carved and weirdly painted, these fantastic bits of the magic Northland add a touch of romance to the camp which can be obtained by no other medium.”[22]

By treating particular components of Native American cultures as little more than toys and games, camp life suggested that indigeneity itself was a kind of game freely accessible to white settler children. Indeed, white American identity itself—constructed not as settler colonialist but as indigenous—can be thought of as a game played for so long, and with such conviction, that it has come to be treated as a kind of reality.

• • •

Though breathtakingly common, Native minstrelsy at summer camps was never ubiquitous. Many parents and camp leaders bristled at the prospect of white children taking on Native American identities, however whitewashed and fantastical; some accused Seton and other Native fetishists of harboring an unpatriotic, or even socialist agenda, a claim that Seton at times also made about himself.[23] In Irene Elliott Benson’s 1912 novel How Ethel Hollister Became a Campfire Girl, the titular character’s mother opposes letting her daughter join the Camp Fire Girls not only because the practice of wearing uniforms with Indian beads “savors of conspicuousness,” but also because she doesn’t want her daughter fraternizing with children “from every rank.” Seton held his ground against these conservative anxieties, denouncing “forms of patriotism that come before morality” and praising the communalist tendencies of Native Americans by comparing them to early Christians.[24]

“I am told that the prejudice against the word ‘Indian’ has hurt the movement immensely,” Seton laments, before going on to blame this prejudice on ignorance about the true nature of Native people.[25] It is one of the ironies of how racism operates that Seton’s anti-Native critics often grasped truths about indigenous cultures that Indian-lore fanatics did not—chief among them a fundamental incompatibility between these cultures and that of the settler colonialists who stole, ravaged, and illegally occupied their land. Fritz Redl, a child psychologist and former camp leader, was one of the most prominent critics of Indian play at summer camp during the first half of the twentieth century. He objected to the “nostalgic reminiscences of a world which our nation has left behind,” an objection that captures the disingenuousness and self-delusion necessitated by playing at white indigeneity.[26] Proponents of Indian play, on the other hand, tended to treat Native cultures like penny candy. (“The best things of the best Indians” was a motto of Seton’s.) In their rush to praise the “noble,” “courageous,” and “spiritual” indigenous peoples of America, many camp leaders completely misjudged both the logical and ethical implications of embracing a white-indigenous hybrid identity.

Today, it is increasingly considered unacceptable for non-Natives to imitate Native people at summer camp or anywhere else. The traditional summer camp of canoes and campfires has largely given way to more modern, specialist pursuits, which tend to be less racially charged. At the same time, the association of camp with Indian play remains strong, and the magic trick of white indigeneity has thoroughly seeped into American culture. “Indianness” is still regularly invoked as a signifier of American authenticity. In the 1919 book Woodcraft Boys at Sunset Island, a Woodcraft “chief” explains during a council meeting: “The pioneers of this country learned genuine Woodcraft from the Indians, and that is one reason why, here in America, we use Indian ceremonies in our Councils—sort of ‘America First’ don’t you know.” The phenomenon of Native minstrelsy and white Americans’ obsession with “Indian lore” has long since spread beyond the summer camp. It is evidenced in Wild West movies, games of cowboys and Indians, Native American Halloween costumes, sports teams and mascots, American Spirit cigarettes, Land O’Lakes butter, and—most perversely—the use of Native American names for US military hardware, from Blackhawk helicopters to Apache and Comanche planes to Tomahawk missiles.

White indigeneity is, of course, figurative. No matter how fervently settlers revere the transformative power of Native minstrelsy or how confidently they claim a Native ancestor, in reality white indigeneity remains nothing more than a game of make-believe. Yet as the hysterically hostile immigration policy implemented in the United States over the past two decades has shown, the illusion of white indigeneity has a dangerous real-world impact. The embrace of such policy among many liberals as well as conservatives confirms the lasting impact of childhood games of indigeneity on the nation’s white population as a whole.

In their study of Native stereotypes in children’s literature, Robert B. Moore and Arlene B. Hirschfelder analyze Robert Louis Stevenson’s racist poem “Foreign Children” from A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885), a collection that is still reprinted and widely cherished today.[27] The poem ends:

You must dwell upon the foam,

But I am safe and live at home.

Little Indian, Sioux or Crow,

Little frosty Eskimo,

Little Turk or Japanee,

O! don’t you wish that you were me?[28]

Stevenson’s labeling of Indian, Sioux, Crow, and Eskimo children as “foreign” is technically accurate from his own Scottish perspective. Yet as Moore and Hirschfelder warn, the poem’s substantial American readership could easily subsume its message into their own subject position—one shaped by the fallacious logic of white indigeneity. Such logic is precisely contained within the poem’s lilting, jeering lines, in the repetition of “little” and the menacingly smug “I am safe and live at home.” Yet it is the last line that is most disturbing, bringing to mind as it does the well-known 1965 photograph of a mother in Bogalusa, Louisiana, protesting school desegregation with a sign that reads: “N-----, don’t you wish you were white?”

Trump’s presidency has exposed the extreme irrationality and tenacity required to uphold what should still be an incoherent identity. The president and his family parade themselves as a return to a fundamental, indigenous Americanness, even as the First Lady speaks English with a thick Slovenian accent. In a now-infamous tweet, the right-wing pundit Ann Coulter speculated on 8 November 2016 that “if only people with at least 4 grandparents born in America were voting, Trump would win in a 50-state landslide.” The seductive illusion of white indigeneity prevented Coulter and her many fans from caring that such a rule would disenfranchise both the President-to-be and his entire family. It is this same seductive illusion that led Ernest Thompson Seton to brand his Indian lore fanaticism as an act of patriotic duty. And it is this illusion that, time and again, encourages white settlers engaged in Native minstrelsy to drown out the objections of actual Native people with the same, bizarre act of projection: “O! don’t you wish that you were me?”

- See Two Little Savages: Being the Adventures of Two Boys Who Lived as Indians and What They Learned (New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1903), p. 19. The novel is still in print, and the vast majority of its Amazon reviews are accompanied by five-star ratings.

- Ernest Thompson Seton, The Birch-bark Roll of the Woodcraft Indians: Containing Their Constitution, Laws, Games, and Deeds (New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1907), p. 16.

- Ernest Thompson Seton, The Book of Woodcraft and Indian Lore (New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1912), p. 9.

- Ernest Thompson Seton, “Organized Boyhood: The Boy Scout Movement, Its Purposes and Its Laws,” Success Magazine, vol. 13 (December 1910), p. 804, as cited in Betty Keller, Black Wolf: The Life of Ernest Thompson Seton (Vancover: Douglas and McIntyre, 1984), p. 161.

- The two quotations are from Abigail A. Van Slyck, A Manufactured Wilderness: Summer Camps and the Shaping of American Youth, 1890–1960 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), p. xx, and Livia Gershon, “Summer Camp, History of,” JSTOR Daily, 26 April, 2016, respectively. The latter is available at .

- Abigail A. Van Slyck, A Manufactured Wilderness, p. xxi.

- Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), p. 5.

- Ernest Thompson Seton, The Book of Woodcraft, p. 8.

- Werner Sollors, Beyond Ethnicity: Consent and Descent in American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 123.

- Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1 (2012), p. 10. Darryl Leroux, meanwhile, explores white French Canadian claims to indigenous identity through the identification of a very distant indigenous ancestor in Distorted Descent: White Claims to Indigeneity (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2019).

- Florence M. Poast, Indian Names: Facts and Games for Camp Fire Girls (Washington, DC: The James William Bryan Press, 1916), p. 4.

- Susan A. Miller, Growing Girls: The Natural Origins of Girls’ Organizations in America (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007), p. 3.

- It was Charlotte Gulick who had coined the abbreviation “Wohelo.” The word became popular and remains a common name for camps today.

- Ernest Thompson Seton, Sign Talk: A Universal Signal Code, Without Apparatus, for Use in the Army, Navy, Camping, Hunting, and Daily Life (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1918). The phrase “the gesture language of the Cheyenne Indians” appears in explanatory text on the book’s title page.

- Ernest Thompson Seton, The Book of Woodcraft and Indian Lore, p. 67.

- Leslie Paris, Children’s Nature: The Rise of the American Summer Camp (New York: New York University Press, 2010), p. 195.

- Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 118.

- Jane L. Stewart, The Camp Fire Girls in the Woods: Bessie King’s First Council Fire (Chicago: The Saalfield Publishing Company, 1914), p. 168.

- Kevin C. Armitage, “‘The Child Is Born a Naturalist’: Nature Study, Woodcraft Indians, and the Theory of Recapitulation,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, vol. 6, no. 1 (January 2007), p. 44.

- Quoted in Michael B. Smith, “‘The Ego Ideal of the Good Camper’ and the Nature of Summer Camp,” Environmental History, vol. 11, no. 1 (January 2006), p. 89.

- Kevin C. Armitage, “‘The Child Is Born a Naturalist,’” p. 44.

- Bernard Mason cited in Leslie Paris, Children’s Nature, p. 208.

- Seton’s biographer Betty Keller points out that his favorable view of socialism emerged under the influence of James Mavor, a political economics professor at the University of Toronto, whom Seton knew while still living in Canada prior to the founding of the Woodcraft Indians. See Betty Keller, Black Wolf, p. 163.

- Ernest Thompson Seton, The Book of Woodcraft and Indian Lore, p. 18.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- Fritz Redl cited in Michael B. Smith, “‘The Ego Ideal of the Good Camper,’” p. 87.

- Robert B. Moore and Arlene B. Hirschfelder, “Feathers, Tomahawks and Tipis: A Study of Stereotyped ‘Indian’ Imagery in Children’s Picture Books,” in American Indian Stereotypes in the World of Children, ed. Arlene Hirschfelder, Paulette Fairbanks Molin, and Yvonne Wakim (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, 1999), p. 58.

- Robert Louis Stevenson, A Child’s Garden of Verses (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1885), pp. 34–35.

Asa Seresin is a writer and a doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania. They live in Philadelphia.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.